In the heart of Soho on a spring afternoon, I had the pleasure to sit down with Gallerist, Photographer and entrepreneur Steve Lazarides, an accomplished artist in his own right. Lazarides was also the renowned agent and collaborator of the infamous street artist Banksy. Ultimately the only person to snap the street artist in action and behind the scenes.

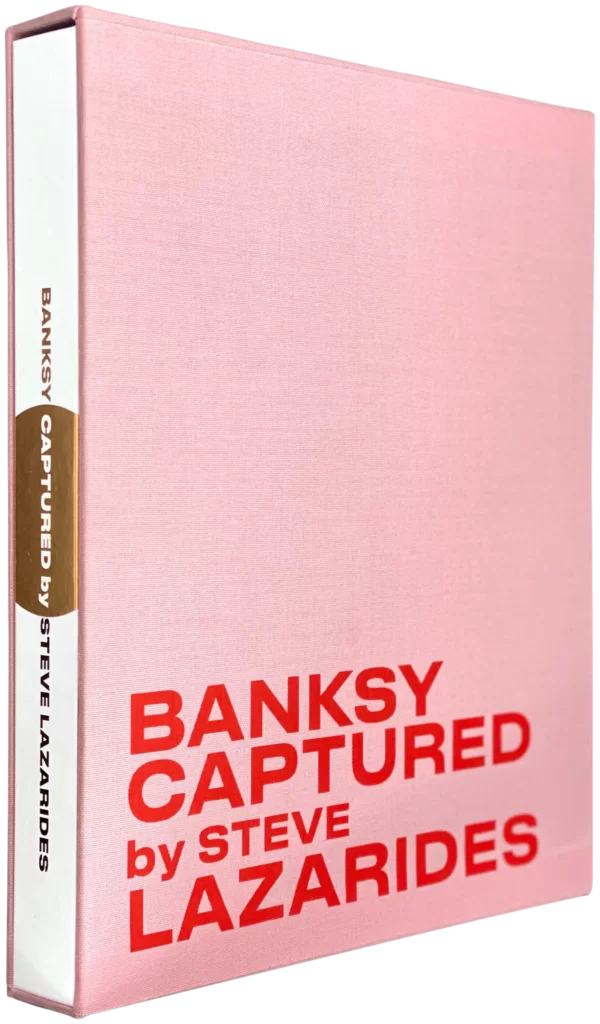

Lazarides is a pioneer of street art and culture, revolutionizing UK street art by carving the way for many artists, facilitating them with a platform to showcase and sell their work, daring to push the boundaries of what traditional thinkers thought was possible at a time when street art was frowned upon and didn’t quite fit the art canon—breaking ground with Laz Gallery and the well-known Picture on Walls website, where you get your hands on limited edition prints from the hottest Graffiti artists. It was one of many things that helped pave the way for street artists today!

The work I did with Barton Hill Youth Club when I was 17 is probably my crowning glory because that’s what started me off on this journey.

Steve Lazarides

As I sat in his office, it was pretty clear Steve was still a mover and shaker with his finger on the pulse as the phone buzzed away. Lazarides began to narrate the journey through the landscape of Banksy, Graffiti and the art world. An expressive and captivating depiction of his well-trodden path as an entrepreneur, Gallerist and photographer.

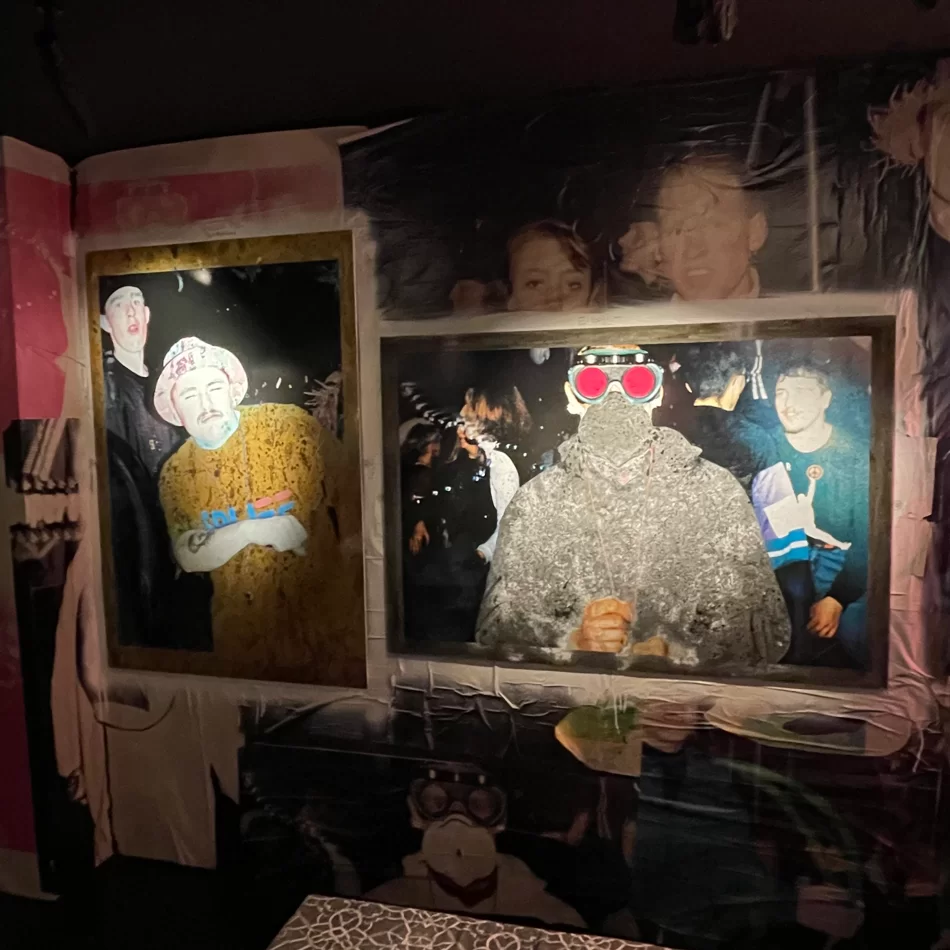

He is now on a mission to reinvent the curiosity shop for the 21st century with street art at the essence, launching the ‘House of Laz’, an immersive sub-cultural space celebrating all things creative as part of his Laz Emporium and his bespoken furniture collection in collaboration with well-known streets artists. Lazarides shows no signs of slowing down. Earlier this year, he revealed ‘Rave Captured‘, his first solo exhibition showcasing never seen before works celebrating the euphoric birth of Rave culture in the early 90s. One of my most interesting interviews to date.

The question that’s probably running through your mind as you read this. Did Lazarides tell me who Banksy is? Well, you will have to read to find out if he did.

Q: Hi Steve, can you please introduce yourself for those who don’t know you?

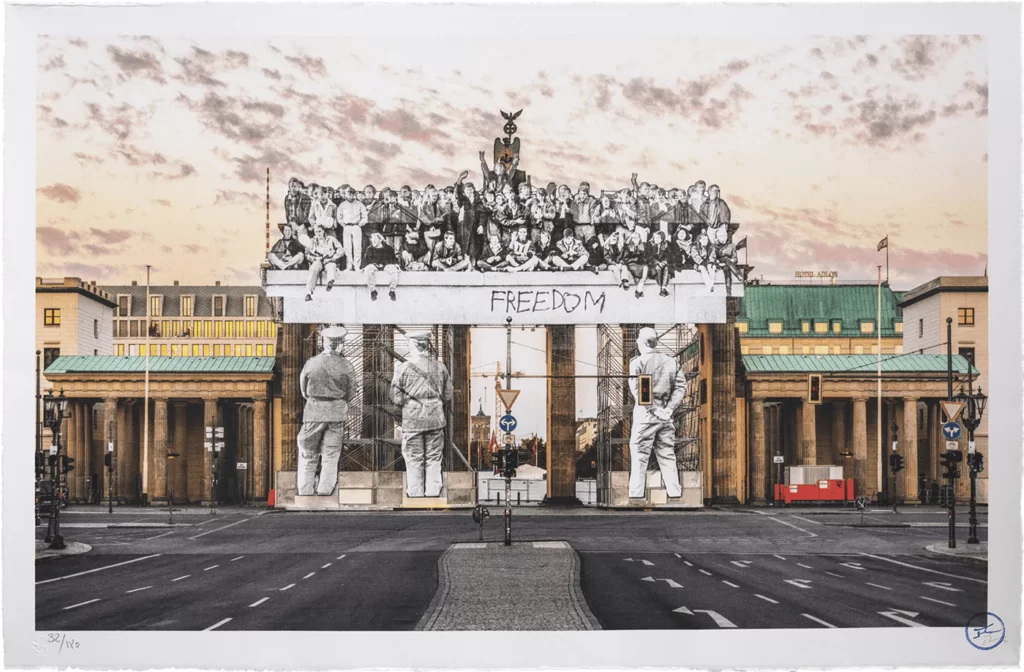

Steve Lazarides : I’m Steve Lazarides. Many things have been said about me, I helped out the street art world become the terrible mess it is now, represented Banksy, broke the careers of Jonny Yeo, JR, Vhils and a bunch of other people.

Now have changed tack after three years in the wilderness, to come up with my new venture, Laz Emporium, where we’re doing all sorts of stuff, we’re a temple to subculture. We’re also making soft furnishings and furniture smuggled into people’s houses. We’re up to all sorts of things, subversiveness through soft furnishings.

Q: You are noted as one of the first figures to spearhead street art and shine the light on many unknown UK artists, including the notorious Banksy. Why do you think this style of art was particularly undervalued at that time?

SL: Street art had a few moments in the sun 1982 was the pinnacle of the New York scene where suddenly all these young artists have been dragged in. There were many artists in New York at the time, and you look at the pictures, it looks like fucking Sarajevo. It’s bombed out, bricks in the road. These were kids that had been in gangs at some point. Not all of them, but the gang thing had changed from the late ’60s as many kids moved into graffiti.

Graffiti has been going on for a long time. The first serious book called “The Faith of Graffiti” came out in 1974, featuring a 12-page article by Norman Mailer, so it was already being taken seriously and looked at by the press even in the mid-70s. But it was always ignored as an art form because it was from the street it was young black artists. Only a few that made it, you can say that Basquiat came through, but I’d say that Basquiat wasn’t really part of the graffiti movement and always wanted to be part of the art world, where graff artists never really did.

Then you had Keith Haring those are two breaking artists. Keith Haring was gay and white, so he fitted within New York’s art world. Angry, young, Black and Hispanic teenagers coming out of New York, the consensus was these people can’t make art. They can’t be artists they’re not thinking about stuff or coming up with overblown stories about their art.

Yet these guys were risking their lives and liberty going out on the tracks and making paintings that were 60-foot long where they only had four feet to stand back from, these guys were fucking geniuses. Then you’d have that thing in the early ‘80s. All the artists got burned. I think everybody got fucked by the galleries. None of the kids made any money. They got pumped and dumped by the New York art world. It was over in a year, and it was brutal. Some of these kids were doing biennale’s back at that point, and it was almost taken seriously. Then they just got dumped by everybody, and the paintings dropped in value. It became valueless.

It goes through that situation, not lost in the wilderness, but it stays underground then, really, until the mid-90s; you got people like Futura, Stash, Blu, and all these guys were doing stuff for Nike such as the Air Force 1 collaborations.

Graffiti was being taken on board by the big brands. That went on for a while in the moment, still not going anywhere, then you get to the late ’90s, and you saw people like Shep, Banksy and Invader and everyone else starting to plough their way.

Apart from Shepard, anyone that was non-American, was vehemently opposed to any commercial work. Then it started coagulating where everybody started came into the same sphere of orbit, those guys came to know each other. It was a creative freemasonry across the world, and everyone knew who everyone was. It wasn’t like now where there are so many people back then the top ten knew who the top ten was, and all were gravitating and working together.

Then I’ve seen Banksy’s work when I’ve gone to take his portrait in ’97. It just started crystalizing from there. With ‘Pictures on walls’, we had everyone passing through when I set up Laz gallery. It was Banksy; It was Zevs, It was Invader. At the same time, you had Johnny Yeo; you had Antony Micallef, you had Vhils. It was a wide group of artists that, through the medium of prints, became fucking known.

You can tie up popularity and Banksy’s popularity into the fabric. We started just as the internet was coming. So for the first time, these artists didn’t need a gallery anymore. Even if you had a gallery at that point in time, you’d only have your works seen in the backstreet of Bratislava. There wasn’t a serious museum or anything coming through, and the internet was a way of getting the art out quicker to so many more people. It truly was – www the World Wide Web, it went out fucking everywhere, and these guys became fucking rock stars.

Q: You were Banksy’s right-hand man who created and provided him platform and structure to sell his work, ultimately the only person ever to document him in action. Did you ever consider what you were building at the time would influence and change the art world?

SL: I had no idea anything we did; anyone would be looking at 20 years down the line. We didn’t have anything in our minds. We were fucking riding the hurricane. It’s taken me until now to get any perspective whatsoever on what happened. We were just stuck in the eye of the storm, and you just moved along. It was a trail of destruction before and after.

I’m not entirely sure that I have created any influence. All I did was facilitate a bunch of artists to get their work out. I wasn’t trying to change or shape or do anything. I was helping artists realize their potential. If that has gone along to shape and change, it would be interesting to know how people think that’s worked if it’s meant that I’ve had some influence in people taking more of a risk in putting stuff on.

But then I look at the stuff we did, and I laid the ground for things people just haven’t followed; they’ve done the easy stuff. So I’ve been rinsed fucking on the commercial level. By the time it gets popular, I’ve been out the scene for like four years and on to something else. I’m not having around really to benefit necessarily commercially from it all.

It’s weird to think that people think I’m some kind of influence. There’s one bit in the question that is true. I am the only person that’s got pictures of him putting stuff up on the streets in probably five or six pieces that were documented. It’s more than that.

Even with the archive, I didn’t even look at it until 2018. Because up until then, it was just a bunch of Banksy pictures, half of which didn’t mean anything. I started looking back on it with a slightly different perspective; it becomes a different thing. I suddenly now do see the value of the archive. When he’s either dead or he comes out. Who’s got the pictures? Who’s got the portraits? Would they come to me? Probably not.

Interesting to think that things we set in motion 20 years ago are seen now as influential. I’ve had a couple of photographers in yesterday. They said Sleazenation influenced them. It’s odd to think that people are influenced by something you did. Just by instinct rather than anything else because we didn’t have a fucking clue what we were doing.

I certainly didn’t have a clue of what I was doing; my way of doing it was like this, so if we had something that sold for 1,500 quid, and everything sold out.

I think do you know what; if they’ve got 1,500, they probably got five. So I put it up for five grand, and then it would sell out. Okay, if they got five, I reckon they probably got ten, then I would put it up for ten. If they got ten, maybe they got twenty. To be fair, they probably got fifty, and that’s how I did it. I could never say the full price because if I have to say, it’s £200,000, I’m just going to start laughing.

That’s how we did it. The rest of it just seemed to be common sense for me. I’m not doing any commercial stuff, keeping it tight. It was a glorious decade. Would I want it back? Would I work with Banksy ever again? The answer is very resounding no I had a good time. I don’t want to do it again.

Anyway along the journey, if we’ve helped people that wouldn’t typically have thought that the art world was somewhere that was a place for them, then that would make me happy. That would be one of the good things that have come out of it. Making art slightly more democratic for a short period of time was one of my crowning glories.

Q: Your camera lens has captured the beginning of many legacy moments in arts and culture. What is your most memorable moment and why?

SL: Oh, that’s a tough one. In hindsight, now I’ve looked through my pictures, not just Banksy related. The work I did with Barton Hill Youth Club when I was 17 is probably my crowning glory because that’s what started me off on this journey. When I look back to it, that was a fucking good photo!

I captured Barton Hill Youth Club, the fucking mythical graffiti club in the middle of one of the roughest areas of Bristol, in the fucking ‘80s!

The thing I like is, at one point, I’ve turned the lens away from the youth club so that you can see what surrounds it with all of these blocks of flats. They are the same blocks of flats still standing now, but they look old. They look like they’re from the 80s; it’s really funny for me. What I captured there was quite monumental.

The other one that I did, I was in New York for September 11th, and I saw the second plane hit. A friend of mine had phoned me who lived there said, “a helicopter had just crashed into the towers, I’m out taking these pictures coming out and meet me”.

I just got in from the UK the night before, and I’m on the rooftop of my friend’s apartment photographing just as tower one falls. I turnround to my mate and said, “mate, I think that thing just fell down”. And he’s like, no, and you couldn’t see due to the enormous clouds of smoke, and sure enough, the tower two goes.

One of the most life-changing parts of my life as far as taking pictures is concerned. I threw all the negatives away because I never wanted to profit from them. In the years come, I know I’ve got great shots in there, and I would use them, which would be wrong. So I threw them away twenty-five rolls of film.

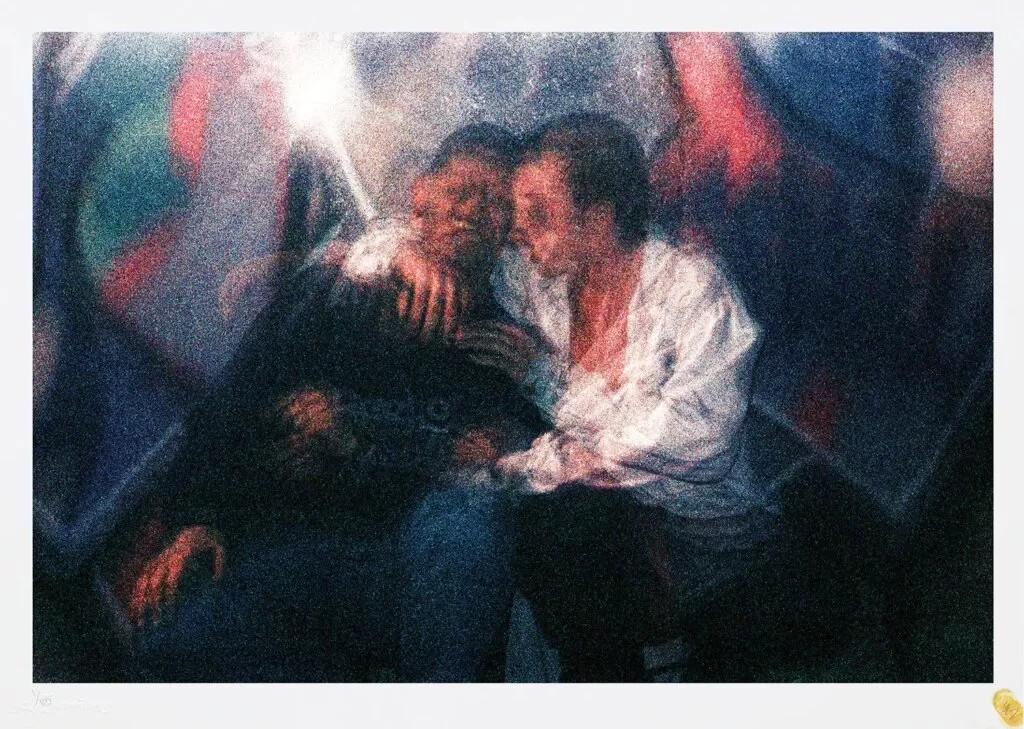

Q: Rave Captured is your first solo exhibition showcasing your capture of the euphoric birth of rave culture across North-East England. Can you tell us the motivation behind this and the importance of exhibiting these works?

SL: I never really went into college. I felt alienated. I was always hanging out with many nefarious characters and DJ-ing to pay my way. It was coming to like my final year and hadn’t come up with any ideas or anything then suddenly rave broke.

The press demonized it. The tabloids were on it non stop. I thought these lads and lasses were still going to work on a Monday. Society is not falling apart. This was the transition from alcohol to drugs being the main club thing. It wasn’t common at the time, you know, fucking pills were twenty quid a pop and stuff like that. These guys and girls were going out and just fucking coming loose in these fucking mad events around the northeast!

I wanted to defend their freedom of expression to go and do what the fuck they wanted. We’re not telling them what to do, and still, they’re a valuable member of society. So get the fuck off their back and let them do stuff. It’s okay. Traditionally a culture where it was like ten pints on a Friday night, have a fight, you know, fuck some bird up the alley, behind the chip shop go home, and then do the same thing Saturday. Suddenly, all the violence is taken out of it, and you’ve got all these guys fucking raving our asses off and hugging each other.

I’m like, what the fuck are they doing wrong? What on earth are they doing to deserve the vitriol you are pouring upon them? Ecstasy and stuff hadn’t hit yet it, so this was like mass lawbreaking, on a vast level. A fucking absolutely joy to see 5,000 people give it to the police and the government. Say what you want, still having a pill and dancing to terrible music.

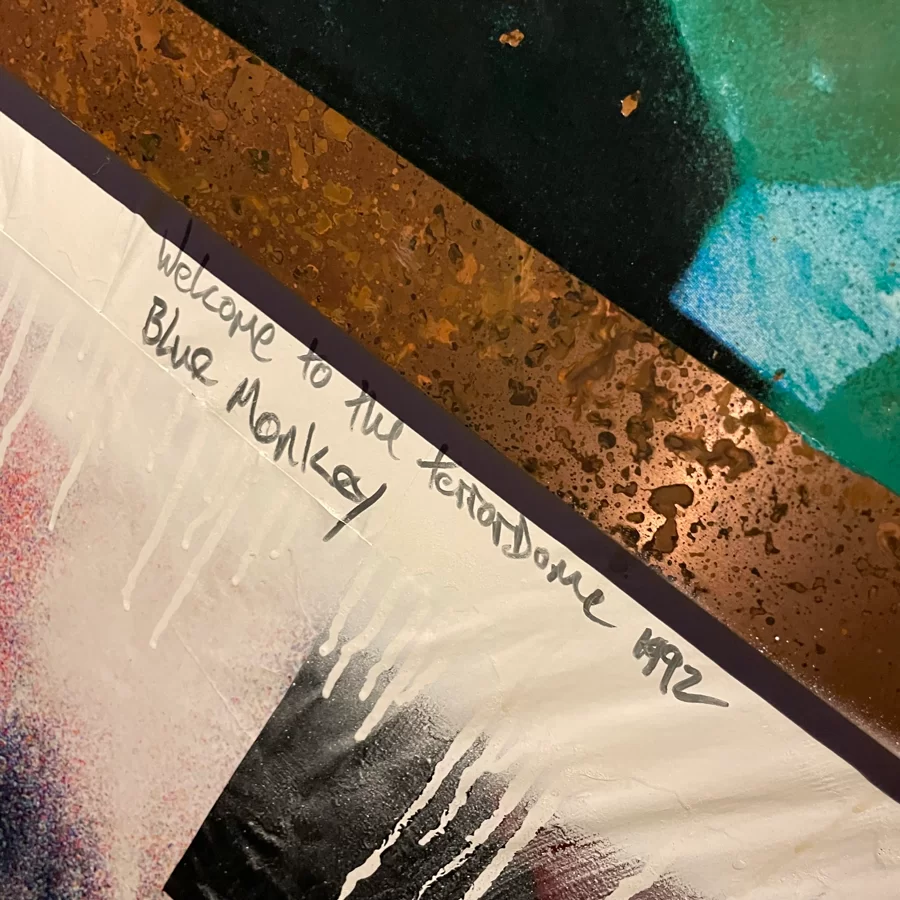

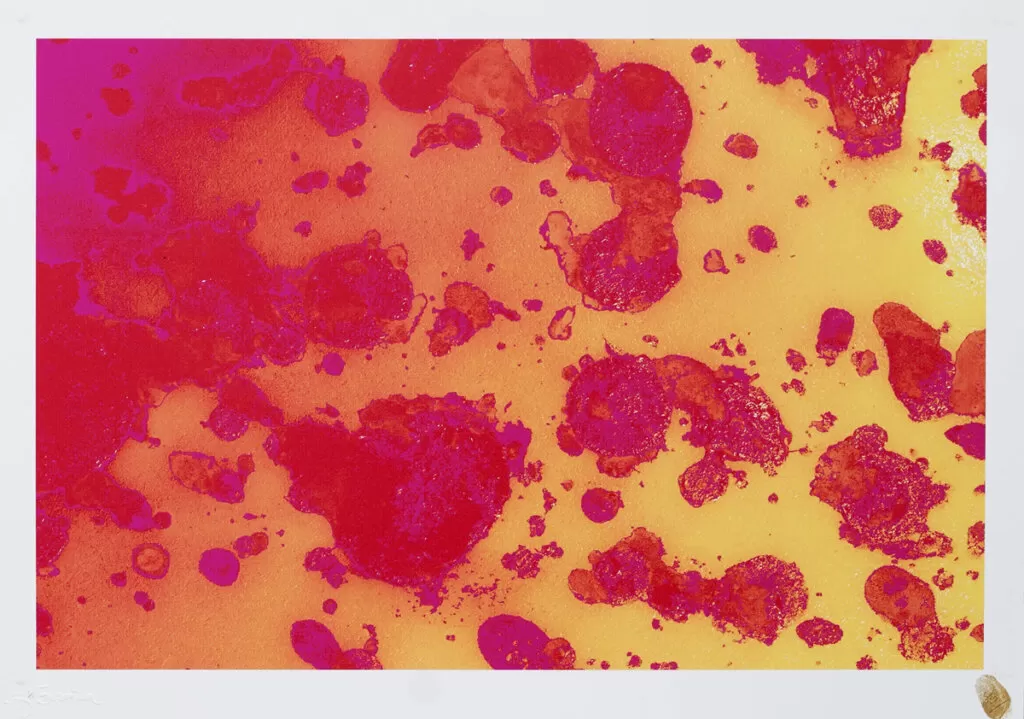

It wasn’t until recently I was looking through the pictures again for something. And I couldn’t remember the name in one of the clubs, so I found my old sketchbook from college from that time, written up in the corner was, “see if you can screen print these photos” that I wrote thirty years ago.

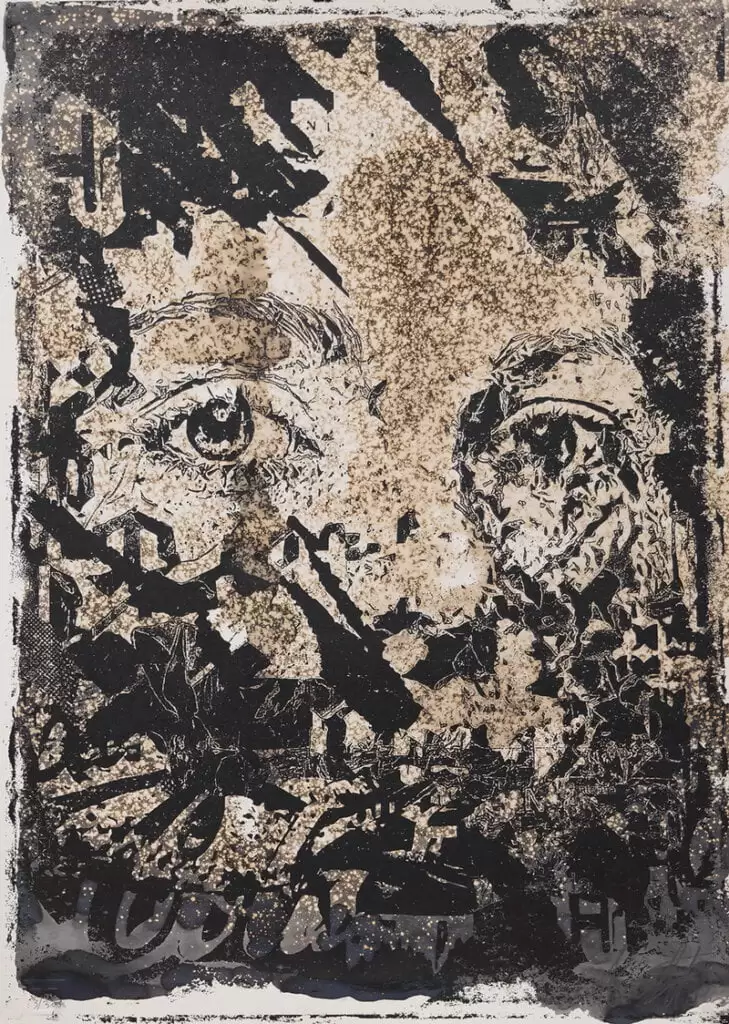

I’ve been experimenting at the moment with screenprinting images and everything else. I thought that was an exciting thing. Why don’t we try to have a play with the images. Make them a bit dreamy and floaty, and they fit perfectly with the exhibition. I thought I’m going to do an exhibition. I’m going to set out the store for how I will do things and how we want things.

I pasted out the basement. The images down there are screen printed on brass and copper. We’ve got a 2k sound system with decks. We’ve put benches and seats so people can just come and hang and sit back and chill out if they want.

And not be another fucking exhibition space. It’s an immersive kind of art speakeasy. I use art relatively loosely because I’m not sure what we’re making right now, but I know it’s something. I can’t put my finger on it. But it’s a slightly different group of people coming through; the engagement with the show was just insane. One of the girls got COVID, so I had to work the shop for a couple of days. Every person who came in thanked us for putting on a good show. We had Damian Lewis in today, the guy from Homeland. I wanted to create a show that showed people that you could do stuff differently.

I wanted to play around with photography. I’m sick of photography being exhibited in 12×16 black and white, fibre-based print in a nice clean black frame with a white border. I’m seeing some of my favourite pictures; this is fucking boring. I’m preparing to do some street exhibitions.

We will be doing drops as well. We will be using our printers to print out big, banner size things, pictures that are 12-foot high by six-foot-wide so we can do photo exhibitions around London for the general public. Old-school D-rings, hanging up because you can’t completely remove the rebel!

Q: Street art was a rebellion against the high hierarchy and its systems. Yet the systems it rebelled against soon consumed it, commoditised it, and turned it into something for sale. What are your thoughts on this?

SL: Graffiti got fucking assimilated. But Graffiti allowed itself to get assimilated. I never got assimilated; I left! You got to roll what you believe in, Listen, to one extent, it’s great; many people are making money, making Graffiti and stuff. In one way, that’s good, I can’t knock people making a living out of it, fair play, but it isn’t what it was, in what I view Graffiti to be. Graffiti was always the tool of the disenfranchised and dispossessed.

It was your weapon in a democracy or even in a fucking totalitarian dictatorship; this was why it was designed in the first place. Stencils were designed precisely for that reason.

The Greeks were writing Romans out around 2000 years ago. It’s an art form that’s been around a long time. It’s a shame that it’s become so anodyne and commercial it is being used as the vanguard for redevelopment and gentrification. It’s a well-used tactic worldwide to bring in the graffiti guys and get them. The single gear bike shops and coffee shops slowly take over the area; the flats are a million quid each before you know it.

For someone like me, the true heart of a rebel, it’s hard to see it slip so far. For so many people, that now can go and paint on the street unfettered, which was a right that was bought for them by the likes of fucking Banksy, JR, Vhils, and everyone else. Where it’s now acceptable to go and paint on the street, you’re unlikely to have your liberty taken away; it’s a different type of person that makes Graffiti.

You’re talking about kids willing to risk their liberty in the past because they had something to say, and that’s the good part of the street. Now that’s gone. It’s brought in a different type of person, it’s brought in your geography teacher in the week, a fucking spray warrior on the weekend, and I think that’s a shame. But there are other things I put my weight behind, like, Alan Ket. He’s got a graffiti museum in Miami. I think that’s good; it’s a fucking OG doing it. On the other hand, there are some terrible fucking places in Germany sprouting up by people that know nothing about the movement of the scene.

Same old shit over and over. It’s a shame to see it go so commercial. I’m glad that no one’s ever asked me we’ve managed to stay relatively clean. People who say that Banksy is commercial, that’s bullshit. That’s pure market forces; he never knew his paintings would be sold for four million pounds, five million pounds a pop.

Things always go generationally, so I’m sure there’ll be a new generation coming through that has something to say, certainly from Eastern Europe.

There’s different spaces all the time for stuff, there’s something to say, people are angry, political situations are fucked up. Why western artists aren’t doing it, there’s so much to fucking talk about, and nobody is saying anything. What the fuck is wrong with you all!

Q: You have witnessed and played a significant role in street art transitioning from the street to the gallery. Do you think street art has its rebellious essence still?

SL: I don’t think Graffiti artists managing to get exhibitions and sell paintings is what made it commercial. These guys are out there fucking ploughing their wears, they’re not taking the sponsorship. Where the fuck else are they going to earn money from?

Because if they can’t do that, then the only people that can do Graffiti are the sons and daughters of the rich and famous if you take it to its logical conclusion. I have no trouble with people selling shit to make money. It’s hard to concentrate when you can’t put food on the table, we’ve all been there when you don’t know when you can buy a tin of beans for the next day, it’s not a great place to be, and it’s certainly not one that fosters creativity because you’re worried about feeding yourself.

I don’t think the transition from the street to the gallery is the problem with its commercialization. The problem with its commercialization is the prominent muralists; they’ve got spaces in town. Here you got Shoreditch in Australia; you’ve got a place, a self-appointed home of street art. I think it just makes it all look shit. Has it lost this rebellious spirit?

As a movement, as a whole, yes. Elements within it, no, there’s still all the taggers that I know that are in their 50s, the fucking DBS crew that came into my place, they’re still active, and they’re my age. They haven’t ever sold out, so is the rebellious nature still there? In some of them, for sure.

Q: We’re witnessing the birth of an entirely new medium called NFTs. Being a frontiersperson, What are your thoughts on this medium? Do you have any NFTs planned for the near future?

SL: I was looking at NFTs quite seriously; then I tried to buy one,I ended up losing the shit out of money, not on buying it, on converting the currency. I lost a few grand just fucking gone that made me reassess my opinion of NFTs. If I found this difficult, then there is a possibility so is everyone else, how widespread is the NFT in the general population?

And how much of it is niche? I think NFTs might be the Sony MiniDisc, and something bigger is coming. At the moment, the currency thing and everything else is too complicated for most people. I did have some NFT stuff planned. Will I pursue it? I don’t know yet. Instead, I may make my currency—an art coin with my whole collection as collateral.

I am a frontier man, and it’s like, I can quite understand it, I don’t know who’s viewing it, why they’re viewing it, how they’re viewing it. At the moment, it seems like its currency. Ask me again in six months.

Q: Curiosity shops have always had a particular attraction. Laz’s Emporium is re-creating the curiosity shop in the 21st Century. Can you tell us what shoppers will experience?

SL: At the moment, it’s ever a moving thing yet you can get everything from a beautifully made, like dining table, for 25 grand, down to a beautifully made tea towel for 40 quid, everything that we’re making as far as I’m concerned is a work of art.

We put as much effort into making a cushion, a tea towel, a sofa, or a print, as we do anything else. Every one of them is a work of art. We’ve got soft versions, pottery, all manner of madness, and it will get madder and madder as time goes by.

Q: Lastly what doe art mean to you?

SL: It depends because I immediately think of the art world when you say the word art, which really pisses me off. It makes me think of all the things that are wrong. When I look at art, I believe art is a fundamental human need.

From Africa to a penthouse in New York, you’d be hard pushed to find anywhere that doesn’t have art in it. And it’s all valid. With art, everybody’s opinion is valid. You cannot ever tell someone they are wrong about looking at a piece of art because it is what they take from it.

That can never be wrong. I have concerns with curators trying to push people into a particular way of thinking about a show; that’s bullshit. I’ll take what I want from it.

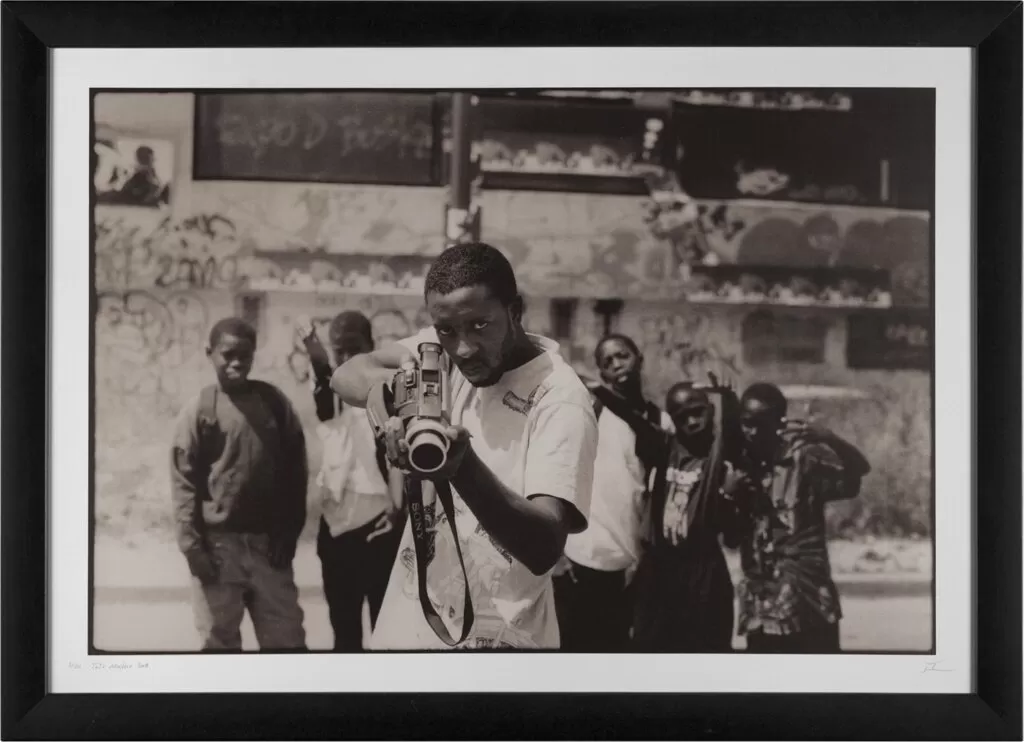

There’s stuff I love. I love one of my son’s paintings. As much as I love the beautiful JR street kid I have in my house, all of the pieces of art that I’ve kept over the years are pieces that have resonated with me. Art, for me, is everything from photography to screenprint. I don’t judge whether it’s an original or anything else. There are so many things that are works of art from the tables we make; it’s a work of art. It’s such a broad church. Art is a thing that makes me happy.

To learn more about Steve Lazarides head over to Instagram

©2022 Steve Lazarides, Laz Emporium