In her transformative practice, artist Maliza Kiasuwa breathes new life into salvaged objects, weaving intricate histories into her deeply narrative fusion of collage, mixed media, and sculpture—an artistic approach that commenced against the turbulent backdrop of the Eastern Congo civil war. While serving as a nurse with Doctors Without Borders, Kiasuwa began crafting dolls from recycled materials for children, a compassionate act that nurtured her path as an artist.

Kiasuwa, of Congolese-Romanian descent, draws heavily from her heritage of Christianity and animism, which is deeply ingrained in African culture. Her life journey, oscillating between Africa and Europe, has blessed her with diverse inspirations that echo her lineage’s sacred mix.

Courtesy of the artist and Morton Fine Art

I instinctively put stuff together and craft what I see

Maliza Kiasuwa

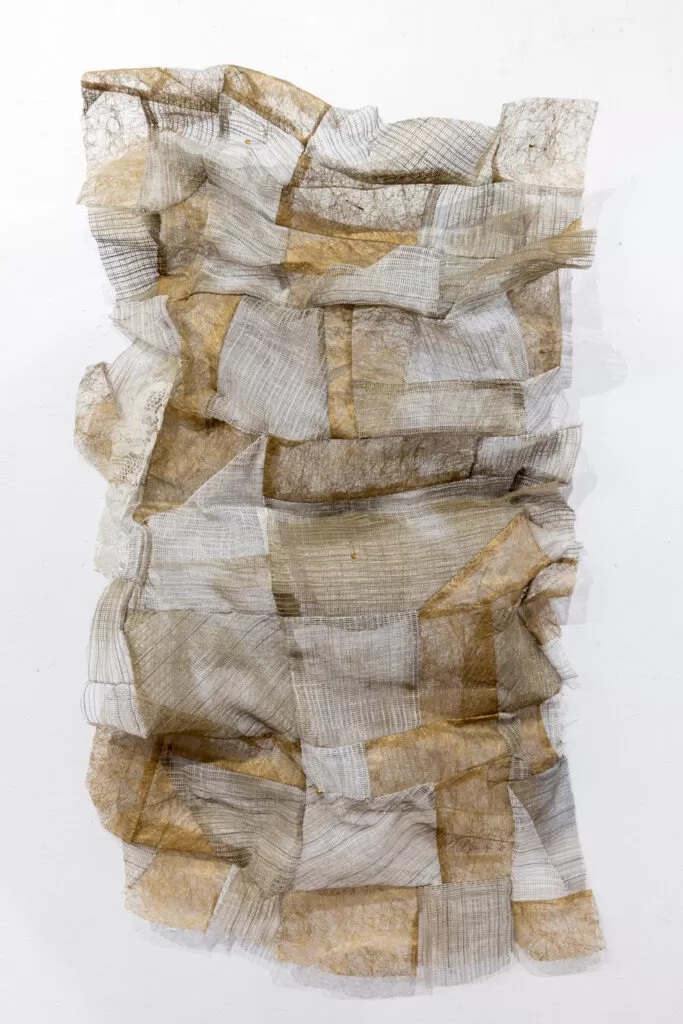

Employing stitching and constructive weaving techniques, Kiasuwa forms an interwoven narrative that elegantly bridges material and cultural dichotomies. This serves as a reflective surface, underscoring the realities of contemporary globalisation and summoning the mysticism associated with traditional object-based animism.

In the recent exhibition “Art as a Weapon” at Morton Fine Art in Washington, D.C., Kiasuwa’s collage work takes centre stage, unearthing and exalting her career while illuminating the complicated nature of cultural and geographic tensions. Kiasuwa has exhibited in Kenya, Switzerland, Italy, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Her practice is not simply about aesthetics and materials; it is imbued with a sense of mission and the humanistic touch of an artist deeply connected to her culture, heritage, and the world around her.

Hi Maliza, How are you doing? Thank you for taking the time to speak with us. Can you please introduce yourself to those who do not know you?

Maliza Kiasuwa: Hello to you and all Art Plugged readers! I am a little overwhelmed by all the media attention in the US, and at the same time thrilled that my art has caught the attention of the public across the ocean. My name is Maliza Kiasuwa. I was named after my Congolese grandmother Maman Elizabeth, and as the Bakongo is a matriarchal society, I also bear her family name. I am many things: a European and an African, a Christian orthodox and an animist, a nurse by training and an artist by vocation. In short, I am a métissein all senses of the word, a weaving of cultures and a free thinker.

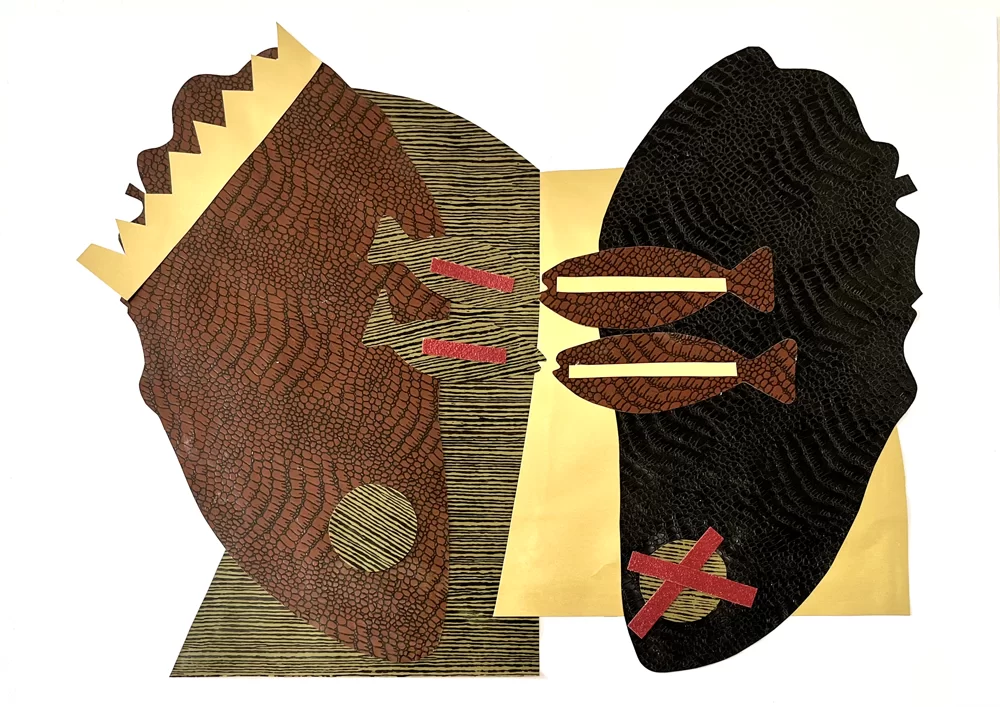

16.5 x 12.5 in.

Collage on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Morton Fine Art

Could you share the journey that led you to pursue art? What were the key experiences or influences that guided you towards your artistic career?

Maliza Kiasuwa: I started crafting dolls for malnourished children with recycled materials during the civil war in Eastern Congo while I was serving as a nurse for Doctors without Borders. During my following missions in southern Colombia, Nepal and the Sudan, I started drawing with dry pastel chalk in my free time. I was inspired by my immediate surroundings: the birds of the Andes, the sadhus of Kathmandu and the dusty skyline of Khartoum. To my surprise, people loved my drawings and asked for more. I did my first exhibition in Khartoum and more in Europe in between missions. We then moved to Kenya, and I became a full-time artist, and ten years down the line I find myself interviewed by an art magazine in the US and one in the UK and can hardly believe it myself. But the US is a nation of self-made people, and as I never went to art school, I guess there is a logic to it…

Courtesy of the artist and Morton Fine Art

Your artistic practice seamlessly interlaces the histories of found objects, creating harmonious dialogues from disparate materials. Can we delve into your practice, inspiration and your creative process?

Maliza Kiasuwa: I am the opposite of a conceptual artist: I instinctively put stuff together and craft what I see, and then I try to figure out the meaning of the outcome. The common denominator of my production seems to be the beauty of nature, the creativity of human resilience and the soul that animates every creation of the Gods. I experiment a lot; I do and undo hundreds of times until things fall into place. Once I find a vein of inspiration, I follow it until it dries out, and move on. Art curators are often skeptical about the constant evolution of my artistic production, which could be perceived as inconsistent, but I am a compulsive artist, and nothing is going to change that. And people tell me that whatever I do, there is a distinct “Maliza” signature to it, so I guess there is some coherence in what is crafted by my hands.

Continuing, how do you select the found objects that you use in your artwork? Are there certain criteria or emotional resonances that draw you to these materials?

Maliza Kiasuwa: Maybe I was gifted with the ability to see art everywhere. I see it in a worn-out piece of sandpaper at my framer’s workshop in Nairobi, in a lovebird nest fallen from a fever tree in our farm in the Rift valley or in a plastic tube found on a building site in Brussels. I assemble stocks of trash, which drives my family nuts, sorting it by fabric or shape. Then I figure out how to give it form and meaning. Sometimes I go on the lookout for more, be it damaged fishermen’s nets or luffa used as sponges by Africans, and sometimes go back home with something completely different that must have been looking for me.

23 x 16.5 in.

Paper and sand paper

Courtesy of the artist and Morton Fine Art

Having lived in Belgium and Kenya, how has this dual experience of locations influenced your understanding of cultural identity, and how is this reflected in your art?

Maliza Kiasuwa: There is much more to it than Kenya and Belgium. I was born to a Romanian mother during the Cold War when the USSR was granting scholarships to African students. I was the first mixed-race baby to see the light in Bucharest. We then moved to Kinshasa, and when the Mobutu regime collapsed, my father sought asylum in Belgium. In Brussels, I lived in the parallel worlds of a conservative Catholic school and our chaotic apartment with my super-orthodox Romanian grandmother and the funky Congolese political exiles that my father was often bringing home.

Then I started exploring the world as a field nurse and ended up on a farm in Kenya with three children, only to move back to Brussels ten years later. As a métisse, I am an eternal foreigner, white to the blacks and black to the whites. In Kathmandu I was constantly mistaken for a Nepalese, so I guess this makes me a citizen of the world and a nomad. My parents transmitted to me the art of resilience, the importance of sticking together through life and respect for the superior forces represented by icons, sacred objects and nature. I guess that they also gave me the greatest gift of all: be free of any distinct identity but mine.

Courtesy Morton Fine Art. Photo credit: Jarrett Hendrix

Your current exhibition, “Art as a Weapon”, at Morton Fine Art, showcases a bodywork encapsulating mixed-media collage and sculpture. Can you tell us more about the essence of the exhibition and what visitors can expect to experience?

Maliza Kiasuwa: I think what is interesting in this exhibition is that it triggers a question and leaves people in their imagination. The work has as much importance as the interpretation.

Can you expand on the concept of “Art as a Weapon” related to the exhibition, your work, and the messages you want to convey?

Maliza Kiasuwa: This quote encourages us to harness the power of art and imagination to effect positive change in the world and to use these tools as weapons in the fight for a better tomorrow.

Over the years, you have continued to expand your practice, transitioning into paper-based collage. Can you discuss a specific piece that best represents this shift and how this piece signifies this change in your practice?

Maliza Kiasuwa: At some stage, I fell on a series of 19th-century prints representing the German ancestors of my children, who are an even more complex mix of origins than myself. I decided to “africanise” them by sticking pictures of tribal masks on their faces and decorating their bourgeois clothes with ethnic patterns. It was a sort of revert genetic experience, and the result was almost surrealistic. I regularly come back to collages because it allows for the most improbable mix of shapes and fabrics, you can represent almost anything with all sorts of fabrics, a pair of scissors and glue. So, expect to see more in between other experiments.

Courtesy of the artist and Morton Fine Art

The studio is a holy place where creativity thrives. Could you share three essential things you need in your studio?

Maliza Kiasuwa: I am a nomad, so my studio is anywhere I produce art. In Kenya, I set my workshop in a huge barn on the farm filled with hay to the roof. There was a straight passage between the haystacks leading to my studio, so it was very secluded, and sometimes I could even see a curious giraffe peeking in my studio. In Brussels, I was invited to a beautiful workshop for a residence in an old residential building, and later I rented a small workshop in an arts and crafts community. As you can see, anything goes. The only thing I carry with me in my studios, except tons of trash and fabrics gathered around, is a loudspeaker, as music helps me to focus and fight the loneliness of creative work. If my studio was a holy place as you put it, it would be more of a cave than a cathedral.

23 x 16.5 in.

Paper and sand paper

Courtesy of the artist and Morton Fine Art

What’s next for you, Maliza Kiasuwa?

Maliza Kiasuwa: If you want to give God a good laugh, tell him your plans! But as it stands, I have applied to the 2024 Dakar Art Fair without too high expectations, as the selection process is very competitive, and I am starting up an art café in Brussels with two African girls, which will be a gallery, a studio and a café serving the best coffee ever grown in Congo by small farmers. I am also watching my children grow with curiosity, with one entering a cinema school, the second being a born musician and the little one being the most weirdly creative writer and illustrator.

Lastly, what does art mean to you?

Maliza Kiasuwa: Art is a way to give back the energy that the Gods have infused in our world and our veins. It has as many meanings as viewers. Emotion is subjective and what you give is not always what is received. I believe that if you need to give subtitles to enable your art to be understood, you had better write books. But answering your questions helps me to realize that there is maybe more to my work than wool, paper and glue. Maybe a little soul?

©2023 Maliza Kiasuwa, Morton Fine Art