Advertisements have long been known to not always tell the whole truth. In this day and age, identity and culture play a decisive role in seeing ourselves as individuals, making purchases, and ultimately how we view the world. We overlook that many of these cultural messages are marketing ploys masquerading as authentic and relatable human connections. A profit-driven manipulation of ideals for many, the divide between fiction and nonfiction doesn’t exist.

A critical subject for British-American artist Danielle Dean who once worked in the illusion industry, witnessed firsthand how identity is constructed through imagery, data and commerce.

I love looking through history, through archives. Advertising is definitely an archive.

Danielle Dean

This stint in the industry has informed her practice as she investigates capitalism, consumerism and identity and how these constructive narratives impact society. Working across multiple mediums, Dean peels away the layered narrative of commercialized imagery through her paintings, sculptures, videos, and performances utilizing the fiction and the aesthetics of advertising.

Dean dedication to her subject matter has developed her a flourishing portfolio consisting of residences at Rijksakademie, The Whitney Museum, including having her work acquired by Stedelijk Museum, Kadist Art Foundation, Hammer Museum, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, CC Foundation in Shanghai, China. As well as being an Assistant professor in Visual Art at UC San Diego.

I have managed to catch up with Danielle to learn more about her practice, the latest exhibition at Tate Britain, how she got started in arts, and more.

LG : Hi Danielle, Nice to meet you. Thank you for taking the time out to speak with me. First things first, so why did you decide to become an artist?

Danielle Dean: Oh my god. I haven’t answered a question like that for a while. I honestly feel – this is maybe a bit of a cliché, but I feel like I didn’t really decide it as such. Like it was just something – well, OK. So I did decide to become an artist for sure, that I did. But what I didn’t decide was my interest in making things and thinking about being creative and the elements associated with it. It was literally the only thing I could do at school. I’m really dyslexic, and I’m not that great at math. I like science but not chemistry, and I really liked biology and history.

But when it came to having to write essays or do anything like that, I could never really express myself very well. So I had to do it through making things. That’s how I got to do – it was always about making – and I didn’t know it was art. I just was like doing stuff.

It was only until I went to do an art foundation that I figured out that I would do jewellery design because that’s more vocational. It’s kind of like one of those things throughout my whole life. It has been a bit like that because first of all, I was like, oh, I’m going to become a jewellery designer because at least I can make money.

Then I realized that I couldn’t do that. I kept making sculptures, and my tutors at Central Saint Martins were like, this is not jewellery. You have to go and think again.

So I then moved to Fine Art Department because it was where I could be the free to do whatever I wanted. Then that’s how it got channelled, OK, if you do fine art, that’s what you end up being, an artist.

Then just one other thing, after that, I couldn’t figure out how to make money as an artist. So I went into advertising and worked as an art director for a few years, which was insane because it’s like the opposite of what an artist wants to do. But it was very creative. So I thought, oh, that’s why I could make a career out of that.

But I’ve slowly became very jaded of that and had to move back to art, and I got my MFA in LA. No one in my family became artists. So it was a real struggle for me to figure it out as it was like it’s very frivolous to my family in a way.

LG: You were working in advertising before taking the deep dive into art. Do you think that informs your practice today? As a lot of your work focuses on the deconstruction of commercialized images and how they affect our identity.

Danielle Dean: Yeah, absolutely. Yeah. That insanely influenced me because I was interested in America before I went into advertising. America equals capitalism to me. So I was born in America, but I grew up in England. So I spent my whole life in England, didn’t know anything about America other than through media. Through films, we all know about America through culture and advertising

So I was still obsessed with that, and I think that’s why I ended up working in advertising because of my interest in those things. It was inevitable that would influence my practice.

Working in the culture industry and then becoming an artist who is unpacking and discussing that. If you’ve had a time in it where you get to see how it’s made, it peels away the illusion because it looks simple. It’s a lot of illusion that when you see a movie, you’re like, “Wow. How does that get made?” The advertising stint helped me figure some of that stuff out and how it is quite a deliberate way of framing our identities in society.

By target marketing, they literally say, OK, this product is for white people of this age and this demographic. There’s a lot of specificity to targeted marketing that I didn’t know before in a detailed way. I just sensed it, and it was so revealing to spend that time in that industry.

Image courtesy of the artist

LG: Where do you think the line gets blurred between the commodity of culture and its authenticity?

Danielle Dean: I think that it’s always blurred. It’s not possible to disentangle that complexity. For sure, that is a thing that affects the work I make, and I try to find ways to acknowledge it in my work or speak on it.

Because to me, it has to do with the embodiment of capitalism how even if we’re resistant to it or know it’s not so great for the environment like it’s catastrophic!

We know that I really distrust people who will say they’re, “I am completely like against capitalism, and it doesn’t affect me at all.” I find that troubling because it’s so embedded in who we are now, and it has infiltrated every aspect of culture. It’s really difficult to disentangle our psychological relationship to it or actual material conditions or material relationship to it.

So I don’t know if it’s possible, first of all, to ever disentangle it. But I think it’s possible to look at it and think about what it’s doing and how it’s affecting us. In turn, that allows us to separate it and see it as something that can then be changed or to make culture that isn’t only made to make money, right?

There’s like a spectrum of extremes. I’m not making my artwork only to make money. Otherwise, I would not do what I’m doing. It’s not at all a profit-making scheme. But money is involved. It would be a complete lie to say that money is not involved.

Money is involved, so that means capitalism is entangled with it, and it’s not just about money because it’s about the conditions of that relationship to that capital.

So I try to work in a way that doesn’t alienate whoever I work with. So we all have an understanding of the whole of the piece, and a lot of the time, there’s some amazing, beautiful stuff that comes out that’s not just about the final product that it happens along the way.

It’s about getting deep into that complexity and that a lot of the time, films that are profit-driven don’t want to sit in the complex reality. They want it to be profit-driven, clean, and efficient to make a lot of money. This produces culture that can be too simplistic sometimes and very problematic.

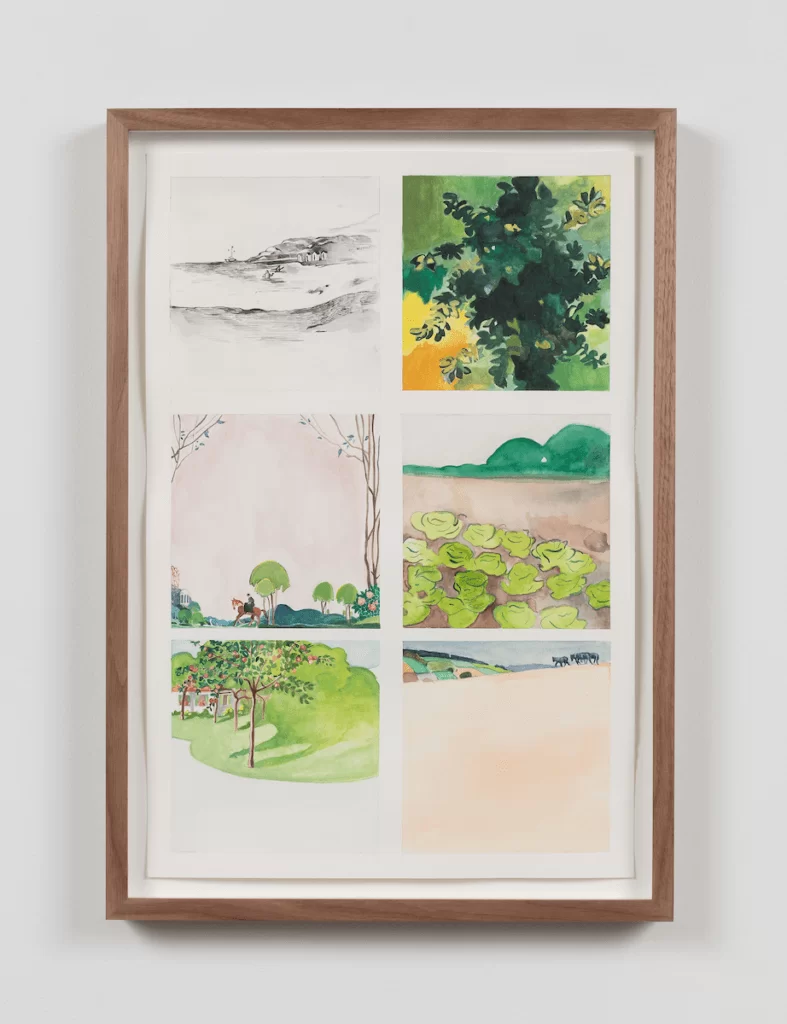

Watercolor on paper

Image courtesy of the artist and 47 Canal, New York.

LG: From starting with your practice till now, your works convey your forward-thinking approach to investigation, which has stood the test of time, especially in this day and age where identity, culture, consumerism and capitalism are more intertwined than ever before, which is an impressive feat. As a sneakerhead myself, my personal favourites are True Red series and Trainers.

Danielle Dean: Yeah, absolutely because also with an investigation it has often to do with me being like, oh, I’m interested in this. Like I’m interested in sneaker culture. For example, I was like, “Why the fuck is this?” I mean, I wear Nikes. You know, yet why is it that there’s such a fetish for these shoes?

Then especially being in America, I was like, wow, this is so much of a thing here than it even was in England. It’s insane, so part of that was like an investigation into that.

Going through the history of Nike ads was so fascinating to me. It’s like a way of looking at history through consumerism. It’s another way of looking at an archive because archives are a big deal for me.

I love looking through history, through archives. Advertising is definitely an archive. It’s not the same archive as what we would usually imagine but, you know, there are adverts from the ‘20s. I mean, sneakers started in like the first TVC, so television ads for Nike was in the ‘80s.

So it’s a shorter history but still is a history, you know, and it – you start actual political movements because they appropriate from what’s going on at the time.

I think art appropriates too. It’s not – it definitely does. So I was interested in that loop of being like, OK, well I as an artist can appropriate from the thing that has already been appropriated and be a part of this like looping round of reinterpreting culture and reusing it in different ways.

LG: You’ve had a very successful art practice with residencies at The Museum of Fine Art in Houston, The Whitney Museum and now the Tate, aswell as having your work acquired by the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles and CC Foundation in Shanghai. How does that make you feel as an artist completing the journey from the studio to the institution?

Danielle Dean: I always feel nervous, like in this interview, I’m half thinking about the questions you’re asking me and half thinking about my installation. Is the sound going to be good? Is the picture good? What are the audience going to get from the work?

Honestly, it’s not easy. I’m so lucky to be an artist, and I love it. But I do get anxious about being out in public cause I’m in the work too. As I put myself out there in multiple ways. Often I’m like, “Why am I doing this?” Like what the fuck?

It’s great to show internationally. It’s super exciting. That’s why you make work so that an audience can see – on the one hand, I’m anxious about sharing it with the audience. But on the other, that’s the point, right? And it’s always going to have something that could be better, and that’s why you make more work too. A lot of the time, if you get to have an experience with the audience and talk to people, then you can get some new ideas and be like, “Oh, wow, like this is what you got from the work, and that’s the beauty of it.

It can spark inspiration to continue to create, as art can be a catalyst for shared discourse. I find it one of the most amazing things about producing culture. It’s like an object outside of you. It’s not you. It comes from you and it becomes part of the public, and the public can respond to it in whatever way they want, and that’s exciting.

You get to be part of a collective of people. Like a lot of people are discussing similar things, right? I’m not the only one. There are so many artists talking about this. So you’re a part of a community of people who are not wanting to accept reality exactly as it is right now. They’re all thinking about that.

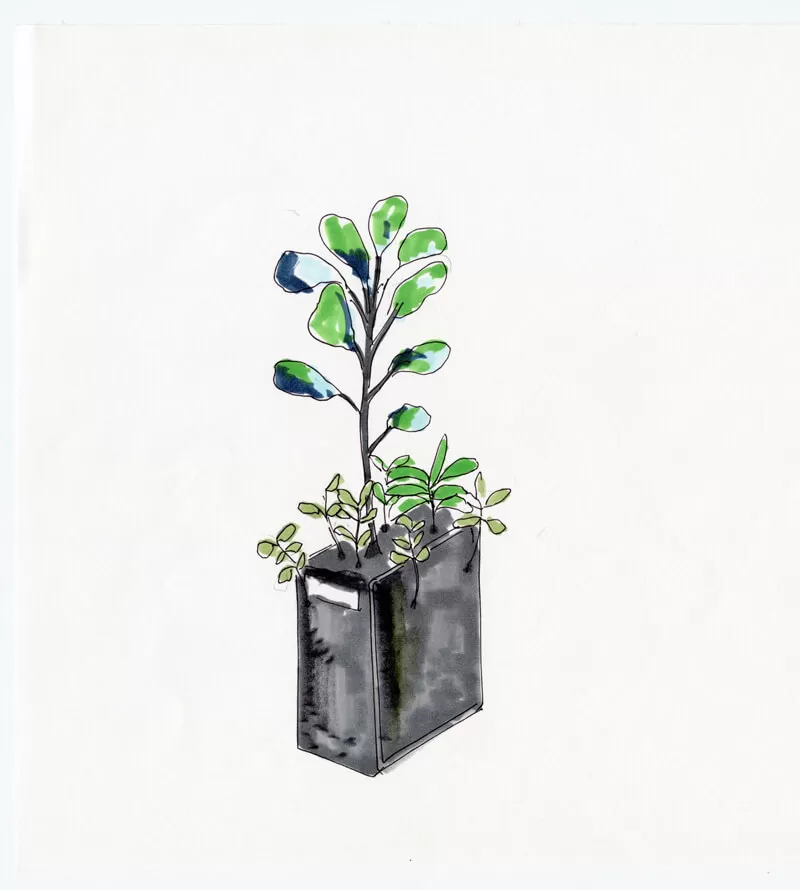

Image courtesy the artist

LG: Continuing on from the studio to the institution. Your discourse has been embraced and backed by the institutions that has enabled you to exhibit across the globe. What advice would you give to upcoming artists looking to take that path?

Danielle Dean: So I really believe this, and I feel like it’s one of those things that get said all the time, and when you’re young, you don’t really believe it. It’s like whatever. But as a young artist, you should do what you believe in and trust, like what inspires you to get out of bed to make work. Not try to do what you think is fashionable or cool at the time because A, you will probably get bored of it, and you will realize it’s not really your thing and B, I do think institutions can see through that, and they enjoy unique perspectives.

Unfortunately, that’s what institutions are always looking for, right? Something that’s new and something they’ve never seen before, and that can be a little troubling in some ways because it has got to do with this pursuit of newness that I think actually is pretty capitalist. So this thing about entanglement, institutions that are really entangled to capitalism. It makes sense for them to like find the new thing.

Regardless of that, that is what they’re looking for. The only way you really do make unique work is to just trust your own thing and go with that.

If you have that lingering thing where you’re like, “Oh my god, I really want to make this crazy thing,” like do it! And then you can have your conversation with yourself with the work, and you develop it. Don’t just be like, “Oh, well, you know, the next cool thing is painting”. I’m going to just do that, or the next cool thing is some subject matter. Ultimately you have to just be true to yourself.

Which is such a cliché, but this is what I tell my students because I think we all enjoy seeing a student do something where it’s like I don’t understand this.

Like, go with that. I don’t know what the hell I’m looking at, but there’s something there, you know, and that comes from just being brave. To get into the deep things that we might not think are right or that you should do.

Because I think my work is so uncool. I’ve always thought that, and I’m like always going, “Oh, how can I like make it more contemporary or like relevant to the subject?” Like some of the subjects I’m talking about, many people are making digital high-res 3D pieces to talk about that.

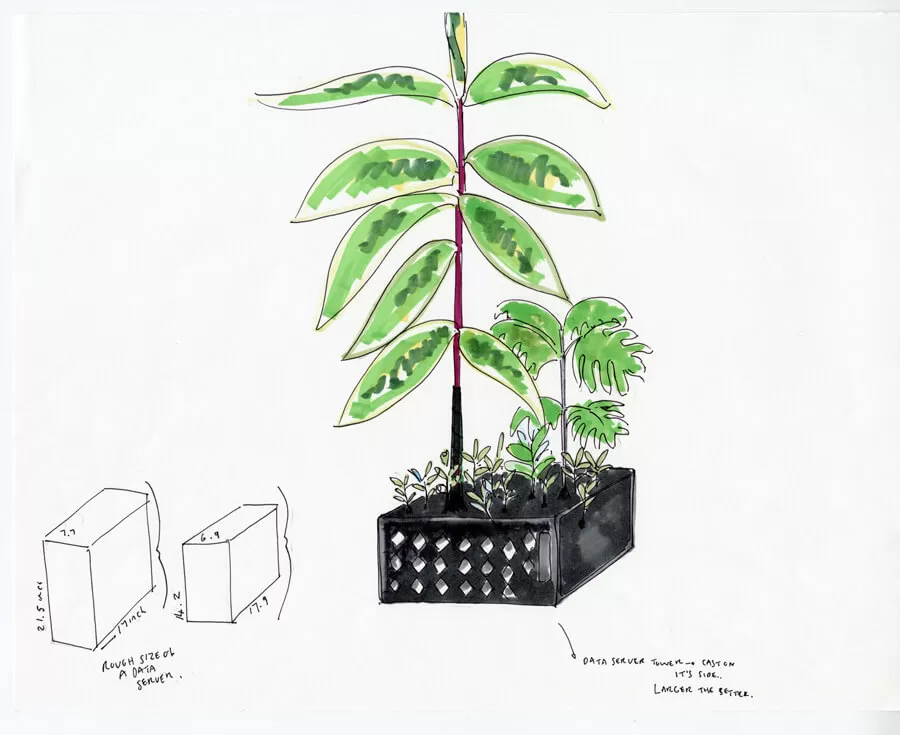

I’m like in this current project painting artificial plants with paint and making a whole forest from hand, which is like totally the opposite of that and not cool at all.

LG: You are currently exhibiting as part of Tate Britain’s Art Now series. Can you tell us about the inspiration behind the exhibition? What can visitors expect to experience, and ultimately how do you feel to be exhibiting at the Tate?

Danielle Dean: I feel really excited and so happy to show the Tate Britain for art now because I grew up in England. Many of my first artistic experiences of seeing art were with my mum bringing me to the Tate Britain because it’s much more of a museum for people who don’t necessarily like art, would go to because of the old paintings and stuff.

She would take me to see the paintings in the turner of wing, and that was a big deal for me. So it’s unbelievable that I get to show here in the same museum. I’m so like, wow, this is unbelievable. I can’t say that enough. I’m like, what the fuck, like that. So anyway, that’s what I feel.

In terms of what you will see, it’s quite like a video installation. So there’s a large anamorphic, which means that it’s a panoramic larger than normal landscape-esque projection. Then there are four monitors in front. So it’s a bit like a video installation experience, and there’s like plants. Not to give it away, but it’s like feels exciting.

There’s a lot to look at. It’s a video that has a beginning and an end. So it’s narrative. It is like a documentary crossed with narratives. It involves real people who are the Amazon Mechanical Turk workers I am working with who do a lot of data-driven work at home.

Then reperforming the events of Fordlandia that was a work camp in the middle of the Brazilian Amazon that Henry Ford set up to yield rubber. So there’s this relationship between thinking about the history of raw materials and the labour around that in relation to a present obsession with data gathering and the human labour behind that industry and that industry being actually about eradicating human labour.

So the data that we’re – that these people are gathering from themselves, from humans eventually is about the Fordist assembly line in a post-Fordist way being more machine-orientated, right? The less humans, the better for efficient capitalism.

So the piece has a lot to do with that entanglement and that relationship and posing the question. “Well, what would happen if humans do use their humanity and come together and say, ‘Fuck this. We don’t want it to be like this,’” because that’s what happened in Fordlandia. There was a big riot.

Danielle Dean currently has an exhibition at Tate Britain ART NOW until the 8th of May 2022.

ART NOW: DANIELLE DEAN

5 February – 8 May 2022

Tate Britain

Millbank

London SW1P 4RG

https://instagram.com/danielleadean

https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/art-now-danielle-dean

©2022 Danielle Dean, Joerg Lohse, Tate Britain, 7 Canal, New York