Witnessing the work of Cuban artist Carlos Martiel is equivalent to an intimate rendezvous with the colonial history of absolute pain, mournful grief, stark violence, displacement, and the turbulent seas of immigration. These are not mere themes; they are viscerally conscious events, deeply entwined with the legacies of Martiel’s ancestors and his navigations through lived experiences, all of which ignite the fire of Martiel’s intense creative manifestations.

The power of art is to move consciousness, spark contemplation, and intrigue conversation, yet how effective is a painting hanging in a white cube while many artists meticulously choose a subject, a message to be conveyed through tangible media? Only a few dare to summon their messages through the medium of their corporeal being. Martiel, unflinchingly, dedicates his very body to this role, subjecting it to duress, thereby morphing it into a profound canvas for the stories intrinsic to the history of the Black body.

Image courtesy of the artist © Carlos Martiel

My body has been my vehicle to the universe and my path, so it makes sense that it has been the centre of my practice

Carlos Martiel

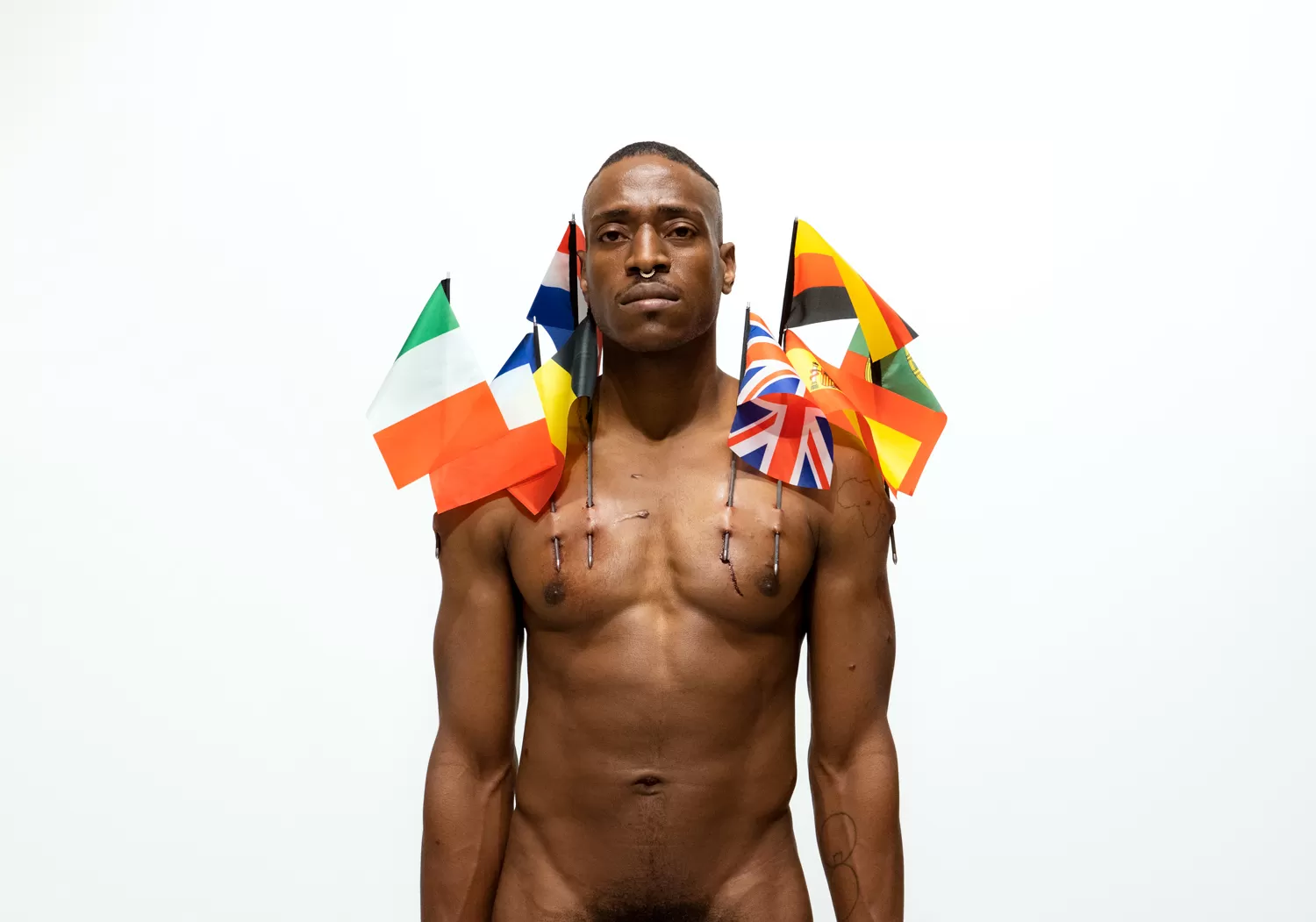

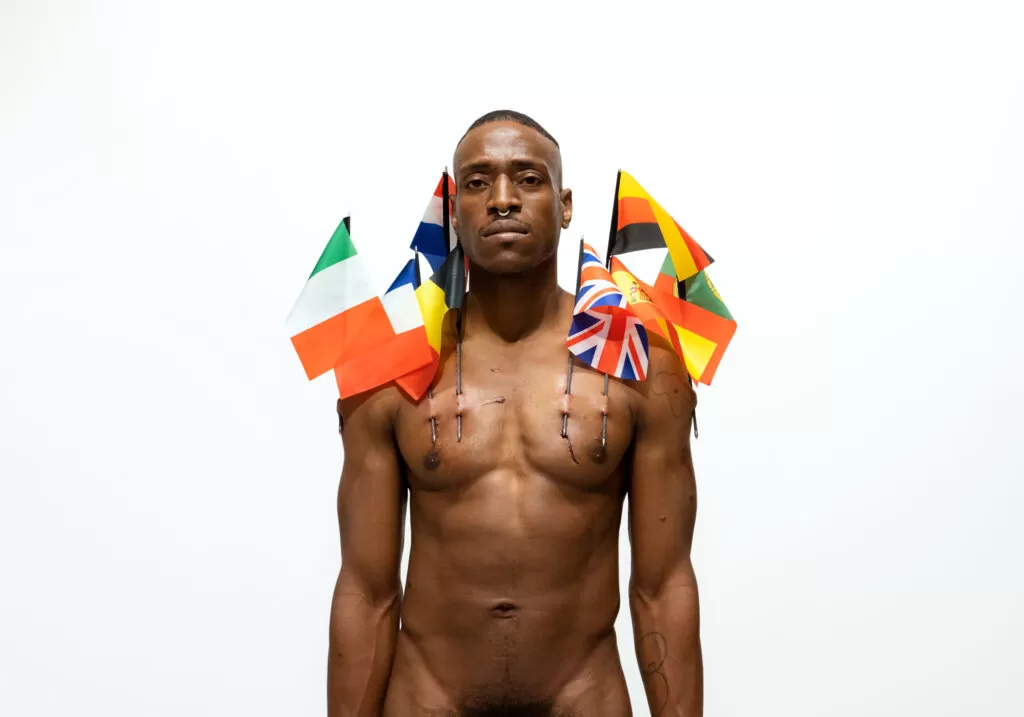

His endurance performances are not mere spectacles but powerful, ritualistic enactments wherein his solitary frame navigates pain and extreme physical stress to forge dialogues on race, identity, colonialism and gender. Martiel’s exploration of pain—severe, piercing, almost unthinkable—transcends mere physicality to communicate his thoughts and analysis of history. His sacrificial offering of self and promise of truth is evident in works such as “Tierra de nadie,” where we observe Martiel not merely standing but enduring; his upper body pierced by eight hand-sized flags, a searing visual metaphor for the ravages visited upon the African continent during the 1880s up until the dawn of World War I.

This piece silently screams the relentless impact on people who have been wrenchingly yanked into slavery and submission through systemic violence and whose homelands have been ruthlessly occupied and plundered by world powers. The demonstrative charge in Martiel’s work does not just illustrate; it ushers the viewer into a realm of experiential understanding of the depth of suffering and strength amidst colonial and systemic oppression. His body, the art of both agony and eloquence, articulates histories and experiences that my words may fail to encompass fully, creating not just an unforgettable visual but a performance where pain, resilience, and the indomitable spirit of the oppressed echo in silent yet deafening roars.

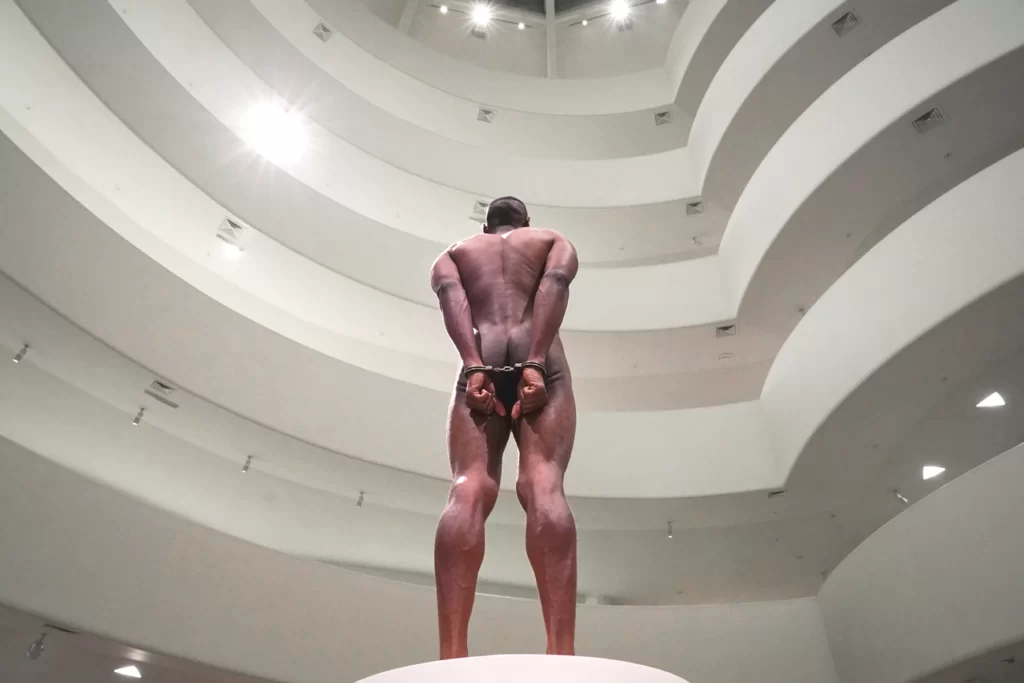

His work has illuminated spaces from The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum to El Museo del Barrio in New York, earning acclaim with awards from the Foundation for Contemporary Arts and the US Latinx Art Forum. Martiel’s practice unfolds as a searing collection of consequences seized from a racialized history littered with injustice, documenting its significance through installations, performances, and more. An artistic experience that will be forever ingrained in your Limbic system.

This October, Martiel will perform “Nobody” as part of Marina Abramović Institute‘s (MAI) takeover of Southbank. We caught up with Martiel before MAI’s takeover of Southbank to learn more about his practice, inspiration, and more.

Hi Carlos, How are you doing? Thank you for taking the time to speak with us. Please could you share a bit about your personal journey, your artistic background, and the initial inspiration that drew you to the world of art?

Carlos Martiel: Hi, I’m doing well. The last few months have been a little difficult because of the cervical surgery I had, but fortunately, I am doing much better now and with the plans of returning to my usual life and my work commitments, little by little. Regarding my journey, in 2005 I started studying art at the Fine Art academy “San Alejandro”. In the second year of my degree, I started to specialise in goldsmithing. In this workshop, I had a teacher who encouraged me to use unconventional materials, so I began to use residue from my own body, such as excrement, semen or blood when producing my work. To give more details on how I utilised those materials in my art, I made a series of drawings for which I had to go to public clinics where the nurses collected blood samples that I later used as pigment. It turned out that, after a while, they started refusing to collect the amount of blood I needed, then they simply refused to collect blood from me anymore.

This became extremely frustrating, and it took me to the decision to work with my body as a whole, implicitly and explicitly, and without the need for intermediaries. That is how I produced my first performance, the first work from those early years, of the very young artist I was, which were closely related to racial issues and what it meant for me to be a Black man in Cuba, to immigration and the impossibility that Cubans have when trying to leave the island, as well as the abuse of power of the local authorities.

How did growing up in Cuba shape your perspectives on race and identity, and how has it influenced your artistic choices?

Carlos Martiel: Being born in Cuba has defined my entire existence, as now it was also defined by me leaving the country. Throughout my entire life, I have had to deal with racism and the specific and harmful way it operates in the context of my country. It is very painful to be discriminated against because of the colour of my skin, or because of my sexuality and the fact that I am gay.

When I was young, I carried so much frustration, anger and discontent. I had no outlet to express this because I come from a family where communication was not the best… at least at that time. So imagine how I might feel back then, with too many things imprisoned in my chest and my head. For me, being an artist was not a choice, it was a necessity because only through art could I express my feelings, my ideas and share the dissident vision of my own reality, as well as embrace my origins and all the magic and beauty that represents being born under this skin.

Image courtesy of the artist © Carlos Martiel

Your practice, is focus on addressing issues of race, identity under systems of violence and exploitation, often using your own body as a medium and that often involve your that involves putting your body through pain or discomfort. Can we delve in to your practice, inspiration and creative process?

Carlos Martiel: One only has the body to experience a part of the external world. I say that because in the human experience, there is so much of this world that is foreign to us and that we will understand. In the same way, you only have the body to experience the greatness of the universe and the life that we carry inside…and we are life, we are a character and we are a personality, animating, moving and guiding a body. My body, the reason why I have suffered so much — because I am Black, because I am queer, because I am a “third world” person because I am an immigrant — my body has been my vehicle to the universe and my path, so it makes sense that it has been the centre of my practice. Right?

Furthermore, the body that I inhabit or is only mine is an ancestral memory of the atrocities and horrors that all my ancestors experienced. Keep in mind that I come from a family of Haitian and Jamaican immigrants, who immigrated to eastern Cuba in the 1920s. This is also something that has defined my practice and has served as creative material.

Everything inspires me; I am inspired by living, the good and the bad of this life; the artist who seeks inspiration only has to look around him. That has been my motto for years as an artist in times of crisis and creative scarcity. Regarding the painful experience, this is an expression of my personal life story as well as the history of oppressed bodies, disenfranchised and subjugated by history made by everyone but only written about by the white man and the white supremacy power they exercised.

Continuing on how do you prepare mentally and physically for performances and take care of your mental health given the intense and often emotionally nature of your performances?

Carlos Martiel: That depends… There is no defined ritual because the context prior to each work is always different. Generally, I try to spend 1 or 2 hours alone, listening to music that relaxes me. I try not to eat in the hours before, I do brief physical exercises before and through the performance, and I try to focus on my breathing.

But I have understood that the point is not necessarily what I do in the previous hours, but what I do every day, and to be honest, I try to have the best time possible to the best of my ability. I exercise, I walk, I take care of my diet, I don’t eat processed or animal-based foods, and whenever I can, I escape. I go to my favourite spa… Like, come on, I’m trying to give myself all the love and care that I possibly can.

Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea (PAC), Milan, Italy

Image courtesy of the artist © Carlos Martiel

How do you see the role of the artist in the current political climate, particularly in Cuba and the broader Latin American context?

Carlos Martiel: Personally, I consider that the role of an artist is to live, experiment and express their rights in case they are violated, with absolute conviction and without fear of making mistakes. I also think each artist chooses the role they want to play according to their life experience, sensitivity and context in which they operate. I am not entitled to speak for others, only for myself.

In my case, my role has been to communicate and transmit my knowledge through art, breaking ties and other people’s criteria around my body. As Black, as queer, as an immigrant, as undesirable, I will rewrite my history in my own terms, period. We should not ask so much of artists. They already have enough to carry with their lives, in contexts where they are almost never understood.

Image courtesy of the artist © Carlos Martiel

How has global events or movements, such as Black Lives Matter, influenced or aligned with your body of work?

Carlos Martiel: Black Lives Matter is an unprecedented movement, I would say, on a global and international scale; Remember, on a local scale, it does have precedents in countries like Haiti, Cuba, even the United States. More than influencing, it is a movement that aligns with my work because the essence of my work has been the rescue of the human dignity of bodies that historically have been deprived of their rights to exist and exercise their freedom for the last 500 years.

Black Lives Matter is an unprecedented movement, I would say, on a global and international scale; Remember, on a local scale it does have precedents in countries like Haiti, Cuba, even the United States. More than influencing, it is a movement that aligns with my work because the essence of my work has been the rescue of the human dignity of bodies that historically have been deprived of their rights to exist and exercise their freedom for the last 500 years.

This October, the Marina Abramović Institute will take center stage at the Southbank Centre’s Queen Elizabeth Hall. Being one of the spotlighted performers, what can attendees expect from the showcase?

Carlos Martiel: So what should they expect from my performance? Another work by Carlos Martiel designed for the context of the United Kingdom. A work that reflects on the historical oppression, racism, and systemic violence that populations from the former British colonies have and keep suffering, outside and inside the United Kingdom.

Photo By Steve Turner

Image courtesy of the artist © Carlos Martiel

Looking back at your career, is there a particular performance or project that you are most proud of or that was a turning point for you?

Carlos Martiel: As an artist, one produces all types of work, some good, some bad, other work that cannot be exhibited under any circumstances and that is below the category of bad, and other work that seems eternal and that sheds truth on certain facts of existence. It is difficult to choose, but if I am forced to do so, I will stick with my current work, such as the Monumento series, the Insignia series, work such as South Body, Fundamento, Tierra de Nadie, or Condecoracion Martiel Carlos. The reason why I choose those is because these works are faithful to history and to the bodies that are a fundamental part of the universe of the oppressed on a global level. I believe that work will always be current — and let it be known that I say this with deepest humility.

Photo Ednid Alvarez

Image courtesy of the artist © Carlos Martiel

How do you see your art evolving over the next decade? Are there any mediums or themes you haven’t tackled yet but wish to?

Carlos Martiel: If life allows me, in a couple of years, it will have been two decades of being an artist. I say ‘if life allows me’ because tomorrow, anything can happen. Nothing is written in stone. I would like to continue working with my body, and I would like to experiment with new media, as I have been doing since 2020. I have so many ideas yet to materialise. I just hope to have enough life for me to do it.

What’s next for Carlos Martiel?

Carlos Martiel: The first part of 2024 is full of work, and I hope that my health will allow me to complete all my commitments and projects. I have some exhibitions and some performances in Mexico City, Panama City, Sao Paulo, and Los Angeles… but the project that excites me most is a solo exhibition at the Museo del Barrio in NYC in spring, which will be my first solo exhibition in a museum from NYC. That has been made possible because I won the Latinx Art Price Double Master, which includes a 50K grant and a show at that institution.

Lastly, what does art mean to you?

Carlos Martiel: I think I’ve already told you… Thank you so much.

©2023 Carlos Martiel