Behind Wilma Woolf’s rigid and data-focused work is a very human, very emotional research. Taking data from “downloaded Home Office spreadsheets, ONS data tables, and reports from the UN and journals” the artist works with numbers on domestic and sexual violence cases, memorializing victims and honouring survivors in her sculptures.

Fresh from a Fine Art MA from Central Saint Martins and shows at Tate, Lethaby Gallery, and Apairy Gallery, Wilma spoke to Art Plugged about a long-held desire to “help make things fairer”, removing oneself from one’s work, and the influence of artists and female friends alike.

Q: First thing’s first, introduce yourself! What do you make, how do you work?

Wilma Woolf: Hello! I’m Wilma. I’m a visual artist and my work includes sculpture, ceramics, photography and installations.

My work relates to equalities and human rights issues and is based in research from the outset. I piece together numbers in downloaded Home Office spreadsheets, ONS data tables, and reports from the UN and journals. I collect individual stories and look for patterns in repeated and lived experiences. I seek to create work that utilities this hard to reach data and translate the issues in a way that numbers cant easily get across. I do this while trying to maintain a true representation of the size and scale of the issue, so it’s a delicate balance.

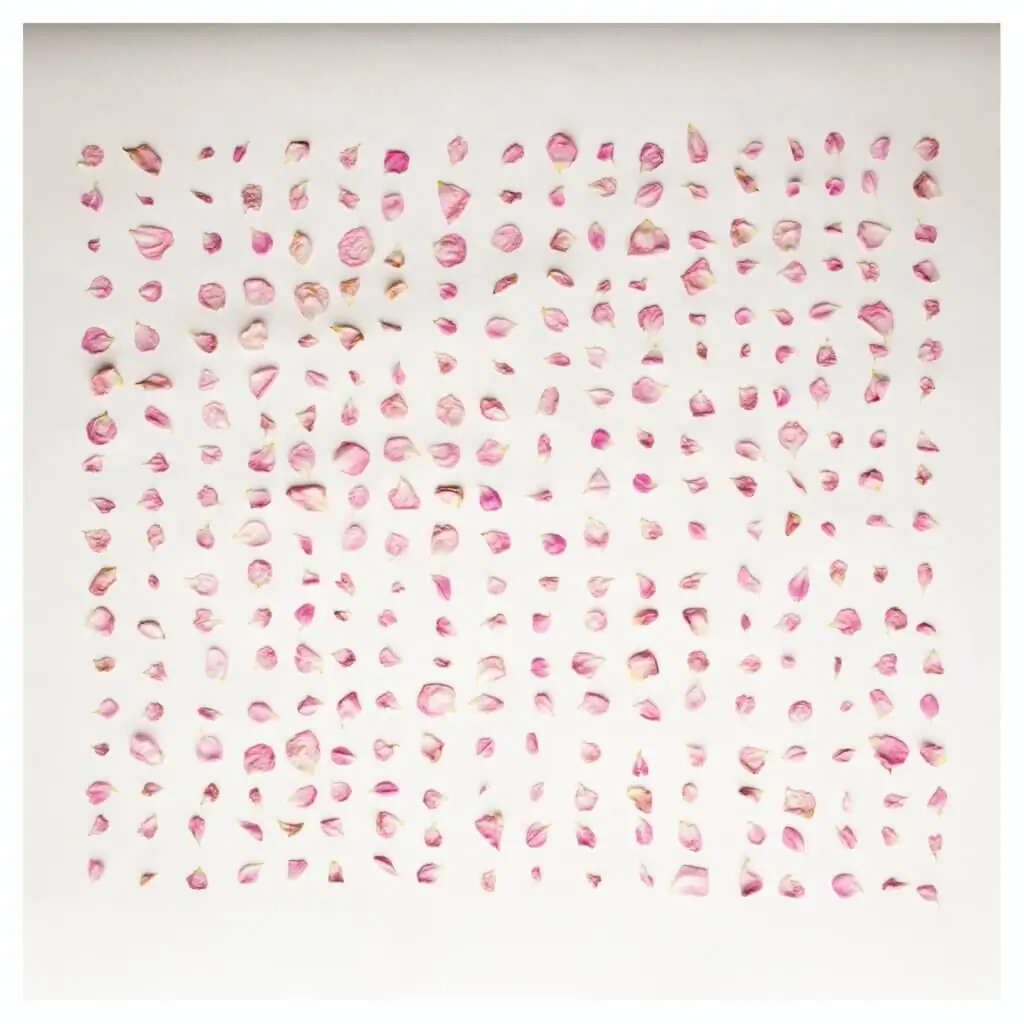

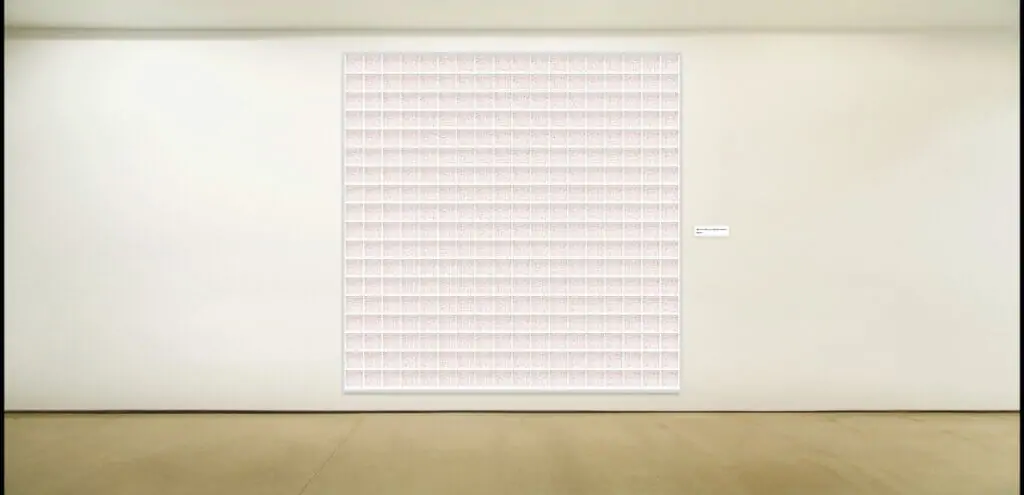

This hard-edged data side of my work is balanced by a need to create work in a devotional manner. My work is often grid like, repetitive and time consuming to produce. I make the same physical movements repeatedly and I try and do this as far as possible, mindfully. For example in ‘I Collected You Carefully’ I collected blossom petals that represented the number of sexual assaults in a year. Each one I picked off the ground purposefully, I dried, cleaned and froze them, knowing they represented a life interrupted.

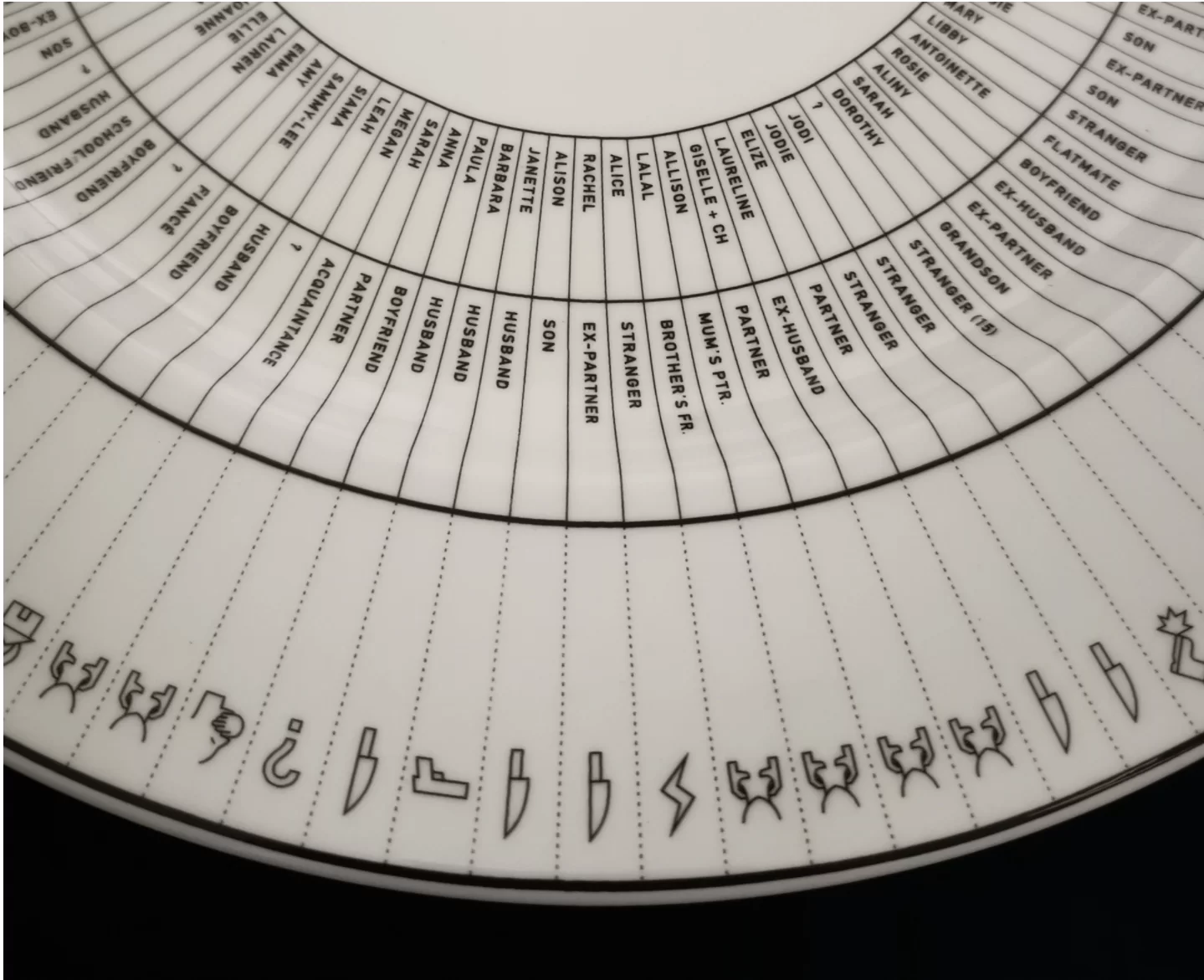

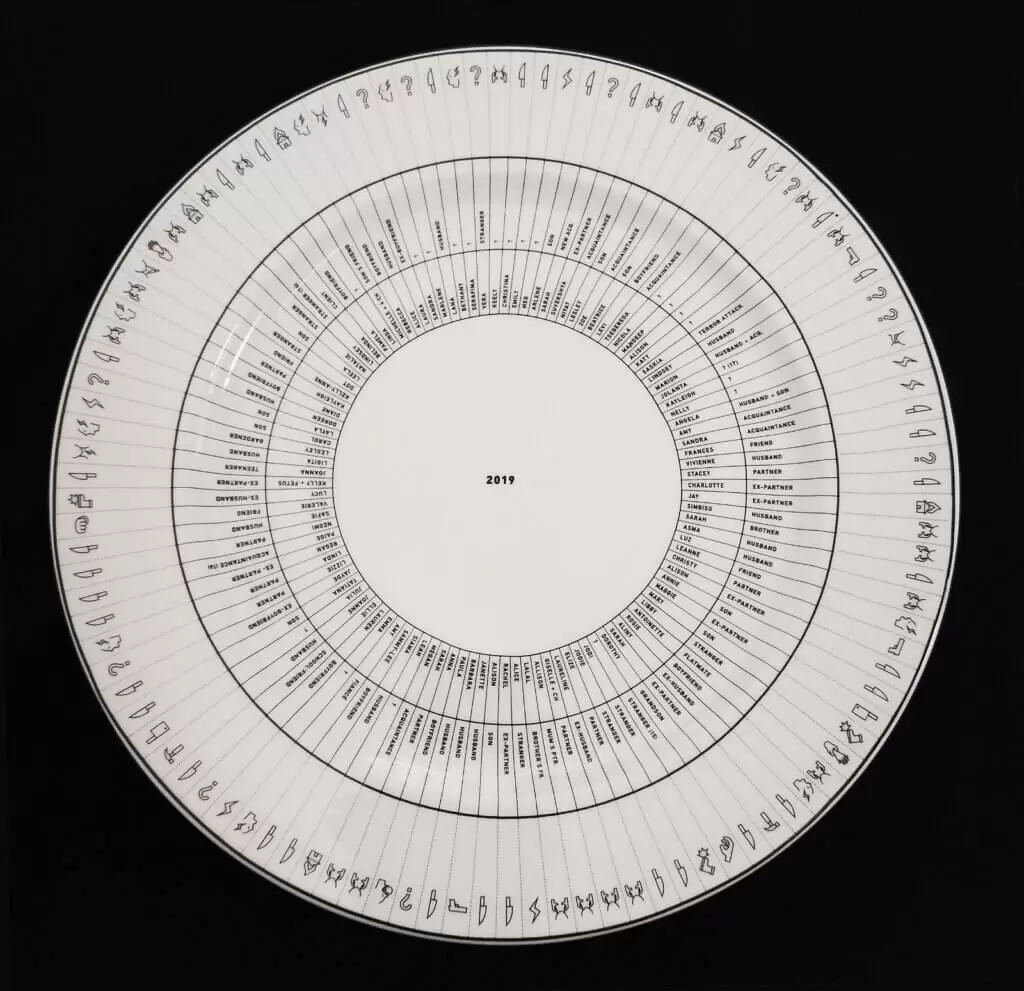

In my latest work, Domestic, I have researched every woman that has been killed by male violence in this country over the past eight years. It builds on data collected by the Counting Dead Woman project (https://kareningalasmith.com/counting-dead-women/). It was incredibly important to me that my intention of the project – that each woman who has needlessly and violently lost her life, was recorded in this work with love. In my research up on seeing her picture, I paid attention to the uniqueness in her face, I said her name out loud, I noted the names she had chosen for her children.

Q: What are the challenges in working this way?

Wilma Woolf: There are many! One of the biggest challenges of working in this way is the balancing act of the immersion of myself in the process of making, but aiming for an absence of myself ‘as artist’ in the final piece. I only want it to represent the issues or people it is about. But when I am making it, there is no separation between the work and me. Whether I’m washing up, making dinner, in the shower, scrolling instagram…I’m thinking about constantly.

After the research phase, I enter a design phase of trying to find the perfect way of expressing the data within a suitable fine art context. I work across different mediums and knowing the data represents real people means I experience quite a bit of anxiety in getting it right. I consult with people it represents, I engage with critical reception to suggestions; I plan who I may need to work with to see if there might be conflict. I question always if I’m the right person to be making the work. My partner describes me during this period as ‘obsessive’ and I wouldn’t disagree.

Q: What would you say your artistic background is? How long have you been working?

Wilma Woolf: I haven’t taken a traditional artistic route to get here. I wanted from a young age ‘to help make things fairer’ as I saw clearly as a young child how unequal life was for so many people. My mum was a single mother, a feminist and an activist. Some of my youngest memories are attending marches and visiting local exhibitions of community protest art. Like all children, I thought growing up that this was ‘normal’ and it was only much later did I realise how much we had been policiticised.

With that in mind, I trod a routine path to work in equalities and human rights policy, holding various public sector roles. Looking back, I can see that I always had an artistic practice. I had a studio on and off when I had the time and money. I participated in some local art events and open houses. However the concept of having a career as an artist didn’t even enter my consciousness. Art-as-career was for rich people who didn’t need to pay rent.

Q: How and why did you go about trying to start an art career?

Wilma Woolf: Several things happened in the space of 3 to four years for this to change. Relationships ended, I become a mother, I lost a dear friend to cancer. I left work partly to process all of this and to cope with a difficult pregnancy and the first year of motherhood. The only thing that remained the same was returning to my studio. Another artist in that studio one day asked me why I was always reading before I started my work. I explained that I use information as my motivation and she simply said, “oh, so it’s your sketching.” As insignificant as this sounds it was sort of a lightbulb moment for me and I realised it was a valid approach. The peace-in-my-brain I felt when the research connected with the making was a satisfaction I hadn’t felt in 15 years of policy work.

I got myself a mentor (knowing no one in the art world, I remember posting an advert on gumtree for a “personal trainer but in art”) to help me consolidate my work and put a portfolio together. My plan was to get in to an evening course somewhere. But my mentor pushed me to apply for an MA in Fine Art at Central Saint Martin’s. The interview was confrontational and hard. If they hadn’t let me on the course I would’ve been so intimidated by it I don’t think I would have tried again. Through the opportunities on the course I have been fortunate enough to have work displayed in various exhibitions including at the Tate, Apiary Gallery and the Lethaby Gallery.

I have a confidence from my prior career that fuels my creative practice. I know the data well and that lends an authenticity to my work I wouldn’t otherwise have.

Q: Who are your biggest inspirations?

Wilma Woolf: The tireless work of Columbian artist Doris Salcedo is a massive inspiration to me. Her work is based in research and collected testimonials and draws attention to human rights issues. Her piece Tabula Rasa is something to behold. It’s a group of wooden tables splintered in to thousands of tiny, minute pieces and incomprehensively placed back together. It references trying to put our shattered selves back together after sexual assault.

Jenny Holzer’s work has also served as a long-standing inspiration as she often integrates eyewitness accounts in her texts. Her piece ‘There was a War’ included 131 individual eyewitness accounts regarding the Syrian civil war. She used interviews with civilian protesters who had been detained and tortured and statements by Syrian children and their parents. It was incredibly upsetting but so necessary and to me, perfect as a work of political art. It was impossible to look away from, but there was a total absence of that experience you can get in a gallery of being lectured at. I sat there on the floor watching the LED words cascade down with tears streaming down my face. Every time I work on a piece of work I think about how she completely removed herself as the artist from that piece and centered it entirely on the people that experienced that war, without pity or exploitation of their experience.

Closer to home, my girlfriends are a huge source of inspiration to me. They are beautiful, clever, loving women and I adore them. Their constancy in my life allows me to be bolder and more cavalier in other life choices because I know they’ll always be there. They have achieved amazing things on their chosen paths and part of me always wants to impress them.

Wilma Woolf: What are you angry about right now?

Wilma Woolf: I am angry that we have a government sending children back across waters in boats and that journalists watch for a story. That Dominic Cummings can be supported for breaking lockdown rules ‘as any father would’ but Priti Patel wants to change the law so we don’t have to provide legal shelter for parents and children fleeing from war.

I’m angry about that the Stephen Lawrence murder enquiry has just been closed. I’m angry that some residents of Grenfell still don’t have homes to live in and no one has been brought to justice.

I’m angry about the deaths of Christopher Alder, Sean Rigg, Kingsley Burrell, Darren Cumberbatch and Sarah Reed – to name just some of the people who have died at the hands of police negligence here in the UK.

I’m angry that Yarl’s Wood Detention Centre continues to detain people indefinitely that have committed no crimes and are separating parents from their children. I’m angry that two women a week are murdered in this country by intimate violence and that during lockdown, it appears that number has risen to three women a week needlessly losing their lives. I’m angry that the devastatingly low number of rape convictions in this country means that rape as a crime has effectively been decriminalised in the UK.

It’s not a pithy answer is it? But there is a lot to be angry about right now.

Q: What’s next for you?

Wilma Woolf: After 6 months off school my son is about to go back which means I can start making work in the daytime again! I’m applying for funding to continue work on Domestic, planning talks and have some potential exhibitions lined up for early next year. I’m always looking at new ways to represent and express data and am currently exploring manipulating shadows and integrating AR in to some of my work. Reaction to my work thus far has been incredibly positive. It’s very exciting and I am thrilled to be in this position. Wilma Woolf is hosting an online talk on Using Data in a Fine Art Practice on October 17th at 3pm.

©2020 Wilma Woolf