Sydney-based artist Suzann Victor has long been a force in contemporary art, solidifying her place as one of Singapore’s most compelling voices of her generation. Her practice, ever restless and incisive, challenges both artistic conventions and societal expectations, approaching them with a multiplicity of perspectives.

Through immersive installations and soul-stirring performances, Victor choreographs a nuanced interplay between physical presence and conceptual depth, affirming her stature as a respected and significant figure on the international stage of contemporary art.

Image courtesy of STPI – Creative Workshop & Gallery, Singapore.

My impetus was to create print in ways that had not been experienced or encountered before

Suzann Victor

Born in 1959, Victor’s career has been a long journey of creative exploration, spanning more than three decades and powered by an unyielding engagement with the politics of visibility, power, and the body in public space. She first gained recognition as the co-founder and artistic director of 5th Passage, a groundbreaking artist-run initiative that operated from 1991 to 1994 at the forefront of contemporary art in Singapore. The project’s abrupt closure following a government clampdown on artistic expression proved formative; rather than retreat, Victor absorbed these tensions into her work, transforming them into a recurring interrogation of authority, control, and resistance.

Victor’s work does not simply occupy space—it unsettles, reshapes, and compels a reckoning with her subject matter. Her practice remains both rigorous and radical—whether through hauntingly beautiful chandelier installations that shift under gravity and time, captivating the senses while provoking deeper contemplation, or through performance-based works that confront the limits of the body. Victor’s practice shatters artistic limits, redefining what art dares to be.

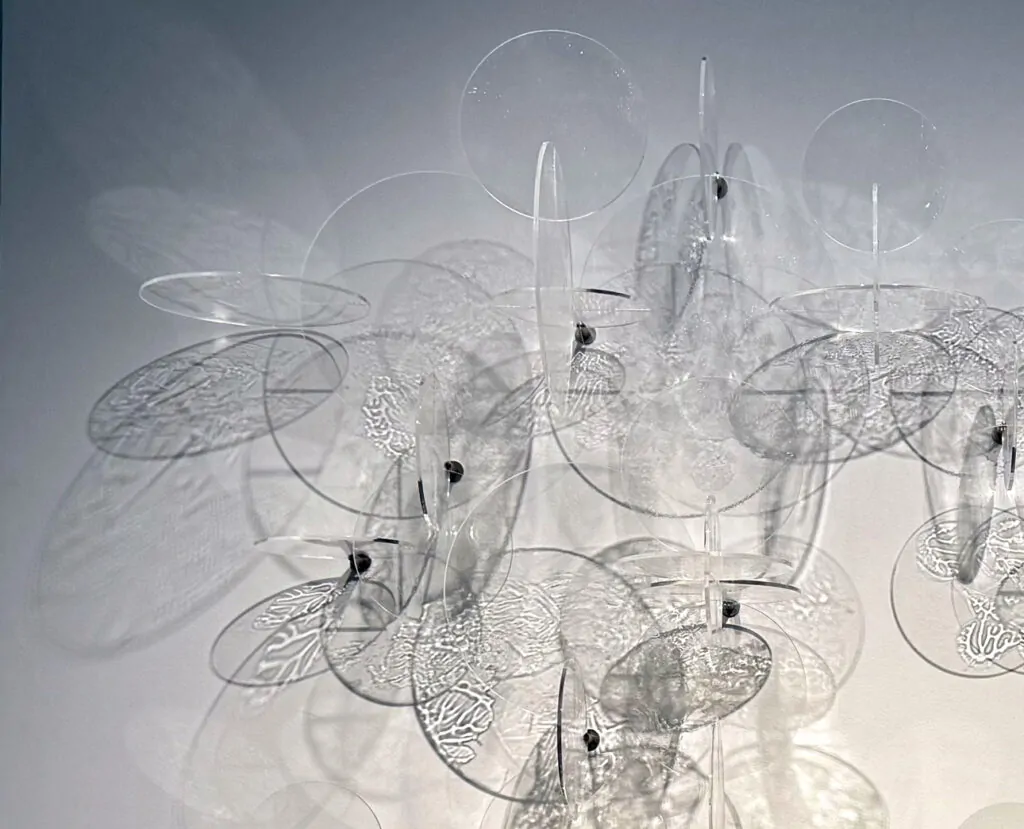

In her latest exhibition, Constellations, at STPI – Creative Workshop & Gallery, Victor transforms printmaking into an interplay of light and shadow. Featuring more than 20 new works, the show invites viewers to engage with the medium in unexpected ways—not only by observing its layered complexities but by actively creating their own fleeting light-prints on the gallery walls, blurring the line between artist and audience.

With works grand in scale, and despite their ephemeral nature, Victor’s impact remains tangible. Her works are held in prominent collections, including the Singapore Art Museum and the University of Western Sydney.

We spoke to Victor shortly after her exhibition Constellations at STPI – Creative Workshop & Gallery.

Your latest exhibition, Constellations, explores the interplay of light, shadow, and materiality in printmaking. What inspired this particular direction, and how does it expand on your past work with sensory experiences?

Suzann Victor: My impetus was to create print in ways that had not been experienced or encountered before. This process evolved into creating secondary light-prints that colonised the walls, simply using the phenomenon of light rather than ink and paper put through a printing press.

These secondary light-prints were not pre-fabricated during the workshop process but manifested in the moment of the exhibition itself, when light turned into shadows that were then recast as light again.

This meant that each work could regenerate itself, occupying dimensions beyond its mere materiality. This presented a unique trajectory, rather than producing an essentialised object that was materially fixed.

Image courtesy of STPI – Creative Workshop & Gallery, Singapore.

You have often worked with unconventional materials—light, water, engineered components. What drew you to acrylic discs for this series, and how do they challenge traditional notions of printmaking?

Suzann Victor: By using every acrylic disc as the printing plate itself to create invisible fractals, I was, in fact, abandoning the conventional tools of the printmaking trade.

For this process, I pressed two discs together to create a vacuum of airless tension so that, when I pulled them apart in particular ways, the deposits of transparent medium would reorganise themselves into fractal maps that emerge literally from between dimensions. When they dry and cure, these fractals literally transform into lenses that generate the secondary light-prints.

As mentioned, every disc in this series was used as a printing plate, and they are, in fact, the printmaking equipment itself. As the instruments of production, they are presented as part and parcel of the artwork, integrated physically, aesthetically, and conceptually. This artwork carries an auto-archive of its own phenomenology, and that really intrigues me.

Image courtesy of Suzann Victor.

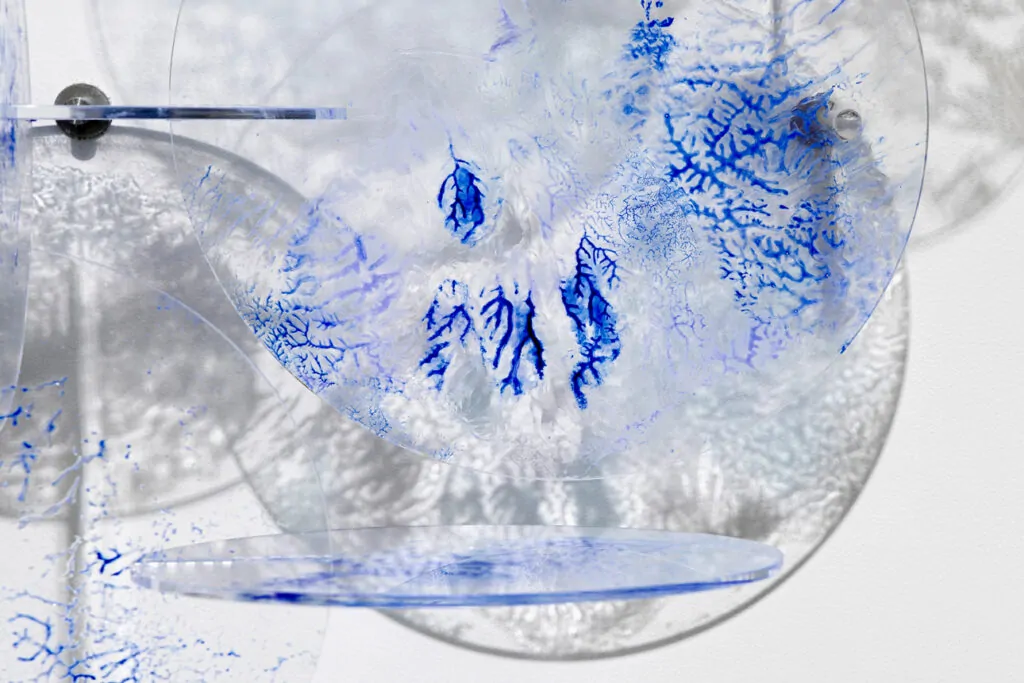

Your method of “Tension-Printing” evokes natural forms like lightning and root systems. How do you see nature’s hidden geometries informing your work, both conceptually and aesthetically?

Suzann Victor: Every disc in each work began as a printing plate that I manipulated. The fractal maps that emerge from between their surfaces transport the viewer from the confines of the gallery into the world of open systems that they mirror—the rivers, their tributaries, mountain ridges, lightning, cirrus clouds, trees, and spider webs to the submerged world of mycelium structures, root systems, mangroves, reefs, and the hidden pulmonary, arterial, and neural networks in human, animal, or other living organisms.

This is the visible and invisible world around us and inside us. The wonder of how they express a self-similarity yet, at the same time, remain widely dissimilar strikes me as a kind of pre-ordained intelligence code. Furthermore, each light-print in the show is, in fact, unique.

You have a history of challenging the traditional role of the viewer, making them active participants. How do you envision audience interaction shaping the experience of Constellations?

Suzann Victor: Viewers are invited to co-author the work by manipulating a light source, such as a torch, to generate their own secondary light-prints on the wall. In doing so, they affect and even recreate the artwork anew. Such an action also alters the appearance of the gallery walls.

This is a powerful act of intervention, as it causes a dissolution of the artwork’s presented boundaries, as well as the light-prints already registered, for as long as it is sustained.

It is also an opportunity for the public to experience a printmaking approach that defies traditional or conventional modes. But, importantly, the viewer is able to conjure his or her own light-prints in situ, within and during the exhibition itself.

The originally presented work simply returns into view when the intervention is over.

Much of contemporary art is mediated through screens and digital spaces. Constellations seems to offer an antidote—an insistence on physicality and sensory immersion. Was this a deliberate response to our increasingly virtual world?

Suzann Victor: Throughout history and in the contemporary, with few exceptions, art has often privileged the primacy of sight over other forms of bodily or sensory engagement. When we consider the ongoing totality of time we spend staring into a screen, it has virtually taken over reality—the time that could have been spent with friends, family, and loved ones, with ourselves, or with the wider community. Our attention has become an auto-commodity.

Making art that emphasises the body as a profound experiential medium, away from the digital screen, has become a more and more compelling trajectory for me.

Image courtesy of Suzann Victor

Your early career with 5th Passage was pivotal in shaping Singapore’s contemporary art landscape. Looking back, how do you see the evolution of feminist and socially engaged art in the region?

Suzann Victor: While the term “Southeast Asia” suggests some form of collectivity, it, in fact, contains a multitude of Others within the Other. The descriptors “Female,” “Asian,” and “Artist” are distinct referents of gender, ethnicity, and work, and yet they are inextricably entangled realities, concepts, and imaginings. As boundaries are dismantled with some success—at times illusorily—more are enacted. Hence, building connection, communication, exchange, and dialogue amongst women artists and cultural workers has become more critical than ever.

Your work has explored themes of postcolonialism, disembodiment, and the abject. Are there underlying political or philosophical questions that inform Constellations, even within its ethereal beauty?

Suzann Victor: Constellations offers an antithetical way of making and thinking about print. One might even say it’s self-conscious. The Tension-Printing series staged transparency as a theatre of paradox, where appearances obscure, disappearances reveal, and presence is absence. In this sense, transparency became a form of absence that conducts visibility like no other filter.

RAINBOW CIRCLE 1 double rainbows

Image courtesy of Suzann Victor.

Many of your works, from large-scale installations to ephemeral light-prints, defy traditional art-market structures. How do you navigate questions of legacy when so much of your work exists in the realm of experience rather than objecthood?

Suzann Victor: I see my practice as a way of reorganising perception and consciousness.

The work is a way of navigating away from an emphasis on the scopic so as to become bodily memory, rather than an experience of the eye alone. By offering an embodied experience, my works expand the agency of the viewer beyond sight, and, in a way, to question the limits of vision as the be-all and end-all of the art experience.

To me, what your body remembers is a dynamic form of legacy.

Another example might be Still Life 1992, which is recognised as one of the earliest site-specific installations in Singapore. Comprising fresh eggplants that invasively protrude out of the walls of 5th Passage, the work, while amusing to some upon initial encounter, quickly becomes discomforting—menacing even.

The recurring phallic forms anchor the site – the publicness of the passageway – as a metonymical stand-in for the gendering of other such public social spaces, as patriarchal space. Such an examination of patriarchy in the structuring of social spaces would not receive significant and concerted attention by academic geographers until the publishing of Linda Peake’s essay ‘Race’ and Sexuality: Challenging the Patriarchal Structuring of Urban Social Spaces later that year in December 1992, and revised in 1993.

Having said all this, there seems to be an assumption that installations and ephemeral works are somewhat excluded from the art market. Several of my installations, though large in scale, as well as smaller object-based works, are in private, institutional, and corporate collections.

Image courtesy of Suzann Victor.

Looking back at your career—from pioneering feminist art spaces in Singapore to representing the country at the Venice Biennale—what do you see as your most enduring artistic contribution?

Suzann Victor: An artist’s practice is a continuum rather than a series of discrete acts that have no meaningful relationship in and amongst themselves. I see 5th Passage, an idea that came to me while commuting on a bus, as a community contribution and the work Rainbow Circle as an ecological one.

5th Passage was one of Southeast Asia’s earliest feminist artist initiatives (1991–1996) to generate new art audiences from Singapore’s de facto community centre—the suburban shopping mall—where two resources were at hand: the readymade public within a readymade public place. As Singapore’s first corporate-sponsored art space, it achieved the aim of decentralisation by bringing art to the masses at the fringes, instead of them being funnelled into museums and galleries in the city centre.

While its media-incited dissolution and decade-long de facto ban on performance art were directly linked to a performance presented at its premises, the aftermath saw a coming together of the art community, whilst also generating intense public debate, artistic and intellectual discourse, and academic writing. Despite the psychic and emotional costs for those directly affected, myself included, a burst of creativity re-emerged—new art projects that attempted to circumvent this new law.

I see this period as a discourse of moral and artistic trauma that produced a distinctly Singaporean artefact—the absent body (of the artist). This form of disembodiment was channelled into a series of performative installations where the body was palpably present despite its absence. My Trojan critique, Still Waters, a performance about performance (1998), notably occurred while the ban was still in place. Attesting to the work’s enduring currency, it was honoured as the theme of the M1 Singapore Fringe Festival in 2019.

Ecologically, Rainbow Circle was a meteorological feat. It produced “objectless art,” where actual rainbows were induced to appear inside the National Museum. Using a heliostat, sunlight was redirected indoors to strike falling water droplets, causing refraction to occur at the 4th Singapore Biennale. Harvested solar energy was used to set up the first pop-up solar charging stations, becoming a forerunner in providing electricity on the go for Singapore’s increasingly digitised world. Two years later (2015), charging stations would become commonplace in MRT stations. In 2018, charging terminals were even installed in public buses plying some routes.

Image courtesy of STPI – Creative Workshop & Gallery, Singapore

If you could leave behind a message or provocation for artists of the future, what would it be? After decades of pushing artistic boundaries and redefining perception, how has your philosophy of art evolved? And as you look ahead, what guiding principles will continue to shape both your work and your life?

Suzann Victor: I see art as generating knowledge in a visual form to make and share meaning, as well as to accumulate and disseminate beyond immediate communities and societies. Miranda Fricker’s landmark study of epistemic injustice has helped me understand the intricacies of how individuals or groups are systemically undermined and denied opportunities to participate or contribute equitably to the production, transmission, and exchange of art and ideas, simply because of an endemic culture of structural bias within a patriarchal system.

In the world of image-making, where images are understood as displays of visual information, they can, in fact, be used to obscure truths.

©2025 Suzann Victor