At the Mead Gallery, Silva transforms quiet interiors and archival photographs into meditations on intimacy, time and the emotional weight of the everyday.

Artist Mike Silva paints like someone whose memories course through his hands. With delicate brushwork and muted palettes, he evokes the taciturnity of private interiors, the soft ache of recollection, and the transience of light. His works don’t merely depict the past—they seem to breathe with it.

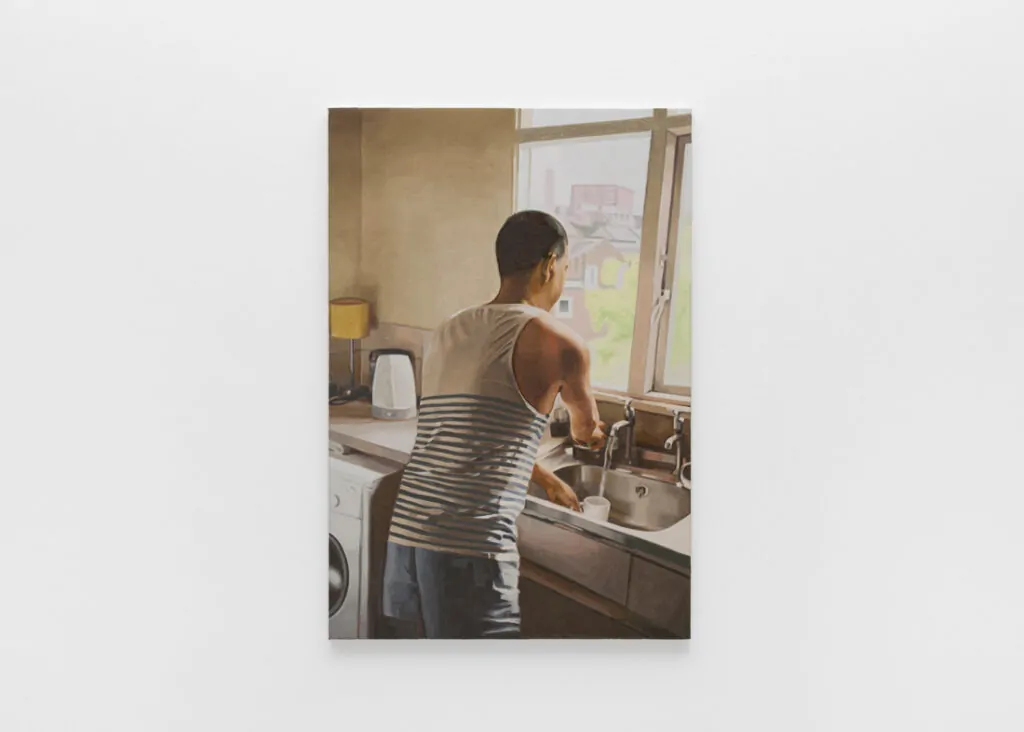

Born in Sweden and based in London, Silva has become known for translating the intimate and unassuming—unmade beds, fleeting glances, the hum of lived-in rooms—into haunting, photorealistic paintings. Standing before them feels less like viewing an image than inhabiting a sensation: not just what was seen, but what was felt.

Credit Peter Davies

If anything, ‘memory’ can often morph into something bigger over time, in the same way a story often becomes embellished through history. Almost exaggerated for effect, but a photo is very grounding.

Mike Silva

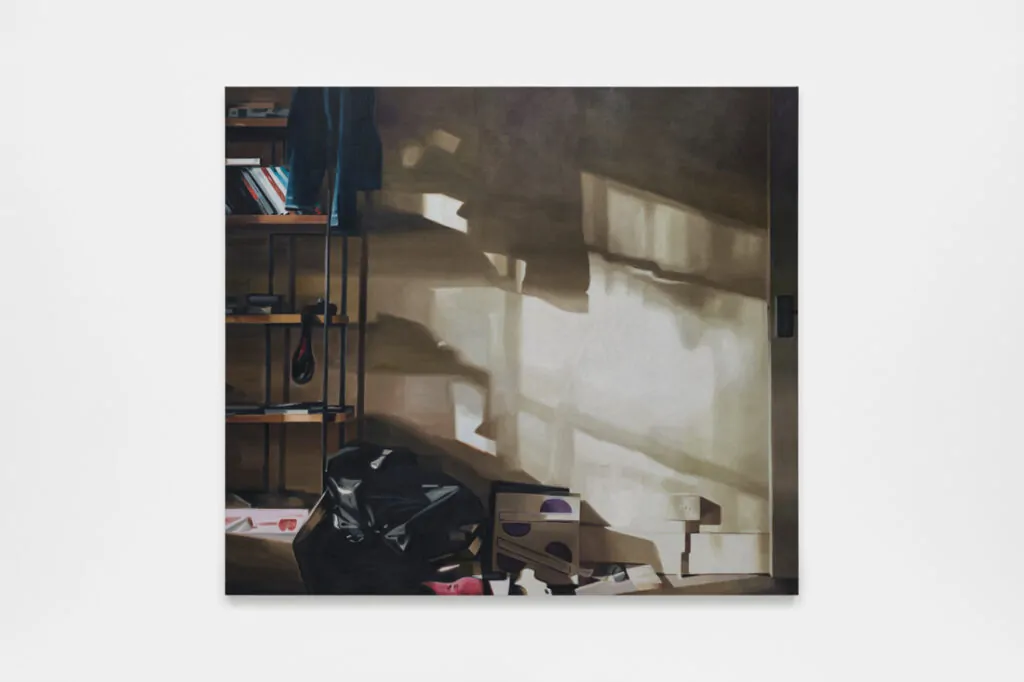

He captures the nuanced play of light as it filters through curtains and across surfaces—skin, fabric, walls—imbuing his subjects with the atmosphere of suspended time. The illumination becomes more than a visual effect; it is a record of presence, a trace of life’s still hours.

But Silva isn’t chasing nostalgia. Working from a personal archive of photographs taken in the 1990s and early 2000s—images that often linger in his studio for years before being painted—his approach lets time settle into the image. ‘A photo is very grounding,’ he says, even as his paintings allow memory to loosen its grip, letting the image blur, shift, and soften into something deeper.

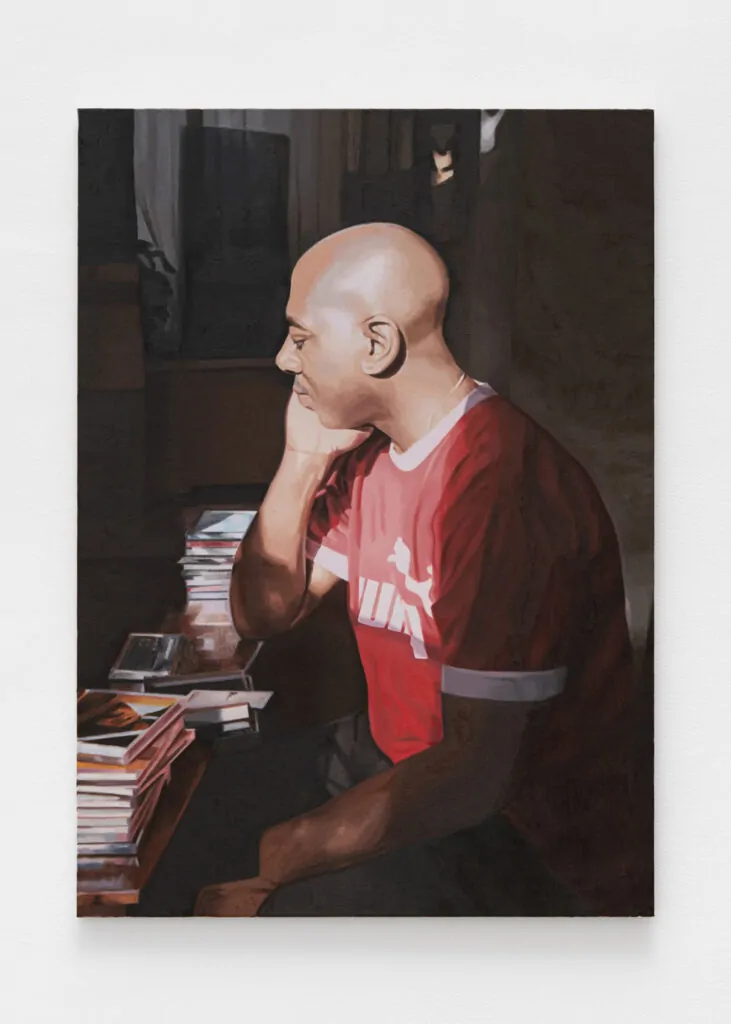

A recurring figure in this evolving visual grammar is Jason, a former partner whose attentive gaze has become an emotional fulcrum in Silva’s work. Through Jason, Silva explores masculinity, tenderness, and the porous boundary between intimacy and distance.

Rendered with a sensitivity that approaches the poetic, Silva’s portraits and interiors are steeped in care. These are not paintings that announce themselves; they linger. They invite pause. They ask you to feel, not simply to observe—as if each one is tuned to a frequency just beneath the surface of everyday life.

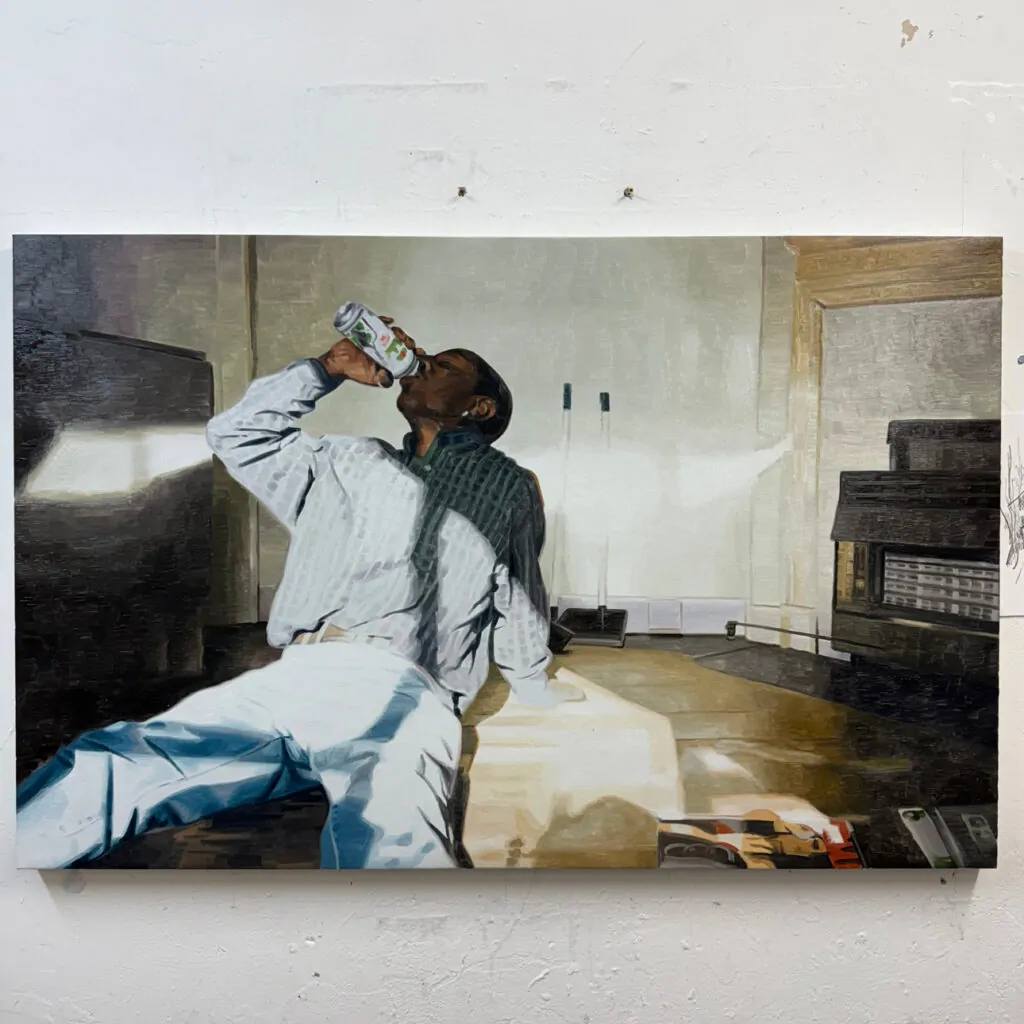

A focal point of his current exhibition at the Mead Gallery is Jason, Tulse Hill (2025)—an enigmatic piece that offers more than a portrait. It captures a narrative of presence: Jason mid-recline, casually drinking, absorbed in his own space. The setting—a modest South London council flat—offers no grandeur, but pulses with significance. A worn heater, scattered objects, and the soft geometry of afternoon light create an atmosphere charged with memory.

The title roots us in a specific place—Tulse Hill—but the painting’s emotional register transcends location. This is not about geography; it’s about the layered textures of a shared life. Jason is not posed for an audience. He inhabits his own moment, lit by a diagonal spill of sunlight that moves across his chest like a measure of time. Silva painted this from a photograph taken on Jason’s birthday—a moment of reflection, not celebration.

Silva’s brushwork oscillates between meticulous realism and gentle abstraction, allowing each scene to hover between remembered truth and emotional resonance. The surrounding details—a television, worn carpeting, old magazines, and the 1980s council gas heater, a staple of British housing schemes—aren’t props. They are anchors. Not nostalgic. Intimate, familiar, and real.

For me, Jason, Tulse Hill becomes a symbol—of place, of memory, of the sacred everyday. It doesn’t demand attention, but gently invites it, and in return, it offers something quietly profound.

As Silva’s archive continues to expand—through snapshots, phone photos, and images drawn from boxes or buried in books—so too does the emotional territory of his practice. These are not simply moments revisited. They are spaces of reflection, reimagined with tenderness, patience, and luminous care.

As his current solo show at the Mead Gallery makes clear, Silva isn’t just looking back—he’s reframing the past through a language of slowness, attention, and deep interiority. In conversation, Silva speaks with the same precision that animates his work: thoughtful, generous, and attuned to the delicate power of what lingers just beneath the surface.

Your work often evokes a sense of memory and quiet reflection. How do you choose which photographs from your archive to transform into paintings, and what draws you back to certain images after many years?

Mike Silva: Usually, photos are tacked onto the studio wall and left there, so they’re always in my eye line and I can work out how certain areas are painted. Occasionally, I’ll find an old photo in a book or in boxes. I’m not an organised person, so this way of finding an image is the best.

Image courtesy of the artist

You’ve described letting your images “cure” over time. Is there ever a concern that memory—and its emotional urgency—might dissipate as the image ages? Or do you trust time to reveal the real meaning?

Mike Silva: If anything, ‘memory’ can often morph into something bigger over time, in the same way a story often becomes embellished through history. Almost exaggerated for effect, but a photo is very grounding.

In revisiting old photographs and painting people who were once close to you, how do you navigate the line between personal catharsis and artistic distance?

Mike Silva: Once an image is painted, you kind of surrender to the fact that this is no longer a photo – it’s a surface. While I’m painting, I’m usually only focused on the process. The touch of the painting can reveal a form of longing (hopefully).

I usually paint friends, lovers or partners, as there’s a familiarity there and they’re part of my world. I have painted images from magazines before, though. I prefer painting people I know, as there’s a sense of intimacy there.

Image courtesy of the artist

How has your relationship to London—particularly the city of the 1990s and early 2000s—informed your artistic language? What does that time period mean to you now, through the lens of your work?

Mike Silva: I never understood what home meant, as I moved around a lot as a kid. I guess home is more about living with people I love. The flats I lived in in London during my 20s were often temporary and short-lived, so I was always documenting these spaces, and the light flooding through the windows gave them a quiet dignity.

Many of your paintings depict men in states of repose or reflection. How conscious is your exploration of masculinity, and what does it mean to portray male subjects in such quiet, unguarded moments?

Mike Silva: I think painters like Alice Neel and Chantal Joffe are very good at painting their subjects in the full-frontal pose. I guess their process is more evident, with the paint handling being almost centre stage.

Image courtesy of the artist

My process is a bit more delicate and muted, so the subject is ‘the thing’. Also, men in front of the camera tend to perform a lot more as a kind of defence mechanism. The culture we’re in now is even more self-aware, so I prefer using candid shots. I’ve always painted my friend Jason, as he’s great at being nonchalant when looked at. He has a kind of disinterested, yet attentive gaze I’ve always liked.

There’s a reverence in your work—for light, for skin, for domestic space—that at times feels like mourning. Do you see your paintings as a kind of elegy? And if so, what are you mourning?

Mike Silva: Yes, there is a kind of mourning, but also celebration too. I reflect a lot, but this experience has altered with the advent of smartphones, where we can casually scroll through images through the years and it blends into one big digital history. Discovering a worn-out photo behind a bookshelf is more rewarding.

Image courtesy of the artist

How has your idea of “home” evolved over the years, and how is that reflected in the interiors and atmospheres you choose to paint? Your paintings often dwell in bedrooms, kitchens, and overlooked domestic corners. What is it about these everyday spaces that continues to compel you?

Mike Silva: These domestic spaces weren’t furnished like conventional homes – they weren’t showrooms at all. They were very functional and utilitarian. The notion of ‘home’ has evolved as I’ve gotten older. Much of the subject matter I’ve used comes from images taken when I was in my 20s.

There is a sense of nostalgia and melancholy in remembering, but I can also use images taken on my iPhone from last year, and perhaps there’s a similar feeling. Initial ideas and subject matter are starting points, but the act of painting can collide with these choices, creating atmospheres and feelings that are beyond my control.

Image courtesy of the artist

In works like Jason (Tulse Hill) and Red, the viewer is drawn into quiet, intimate scenes. What role does ambiguity play in your paintings, and how do you decide what to leave unsaid?

Mike Silva: The recent painting Jason/Tulse Hill was from a snapshot of my then-partner Jason on my birthday in 1998. I recently discovered the photo in a pile of old snaps and loved how the daylight pouring into that room framed the scenario. It’s a very personal image, but also an everyday image.

There’s a sense in your work that the world is quietly falling away, leaving only light, texture, and memory. Would you say your paintings are, in some way, about disappearance?

Mike Silva: I don’t consciously want the images to disappear. Perhaps the painting process is part of that – the materiality of paint coming to the foreground. The image sort of evaporates when the viewer is close to the surface.

Image courtesy of the artist

The Mead Gallery exhibition marks a significant moment in your recent career. How did the new setting at Warwick influence your curation of the show, particularly in contrast with its earlier iteration at the De La Warr Pavilion?

Mike Silva: The Mead space gave the work a whole new context, including a purpose-built wall to hang the new painting Jason / Tulse Hill. The De La Warr space faced a row of windows that looked out onto the seafront. It was very beautiful and atmospheric. It seemed very connected to ‘light’ itself.

Credit Art Plugged

With your evolving archive and the meditative pace of your practice, how do you see your body of work developing in the coming years? Are there new themes or directions you’re beginning to explore?

Mike Silva: I wish to paint more landscapes. I have so many images of cruising grounds from the 90s which I’d like to revisit. I also have recent snaps of landscapes that I’d like to use. There are so many possibilities.

©2025 Mike Silva