British visual artist Mat Collishaw‘s practice represents a sublime synergy of technological skill and conceptual depth within the spectrum of artistic brilliance. A luminary amidst the seminal cohort of British artists who blossomed from one of the meccas of British art, London’s Goldsmiths’ College during the twilight of the 1980s.

Where his love for photography and video matured, shaped by an interest in pathological literature. Collishaw’s journey into contemporary art began with an explosive bang as he unveiled his now-iconic work, Bullet Hole (1988), a shocking, intimate photograph of a bullet hole through a human scalp mounted on 15 lightboxes. Shown in Damien Hirst‘s groundbreaking Freeze Exhibition in 1988 served to amplify Collishaw’s debut. An epochal event that galvanised the art world and spurred the YBA’s (Young British Artists) movement.

From that point, Collishaw’s notoriety for his expression which delves into the crevices of imagination, grew, celebrated for intertwining the natural with the manufactured, the organic with the fabricated, that engulfs viewers in a whirlwind of sensations, from the chasm of wonder to the grips of fear, from the pinnacle of reverence to the edge of breathtaking beauty.

As an artist, you always want to try and experiment and find new ground, and one way of doing it is using new materials, mediums, techniques, things that have only just arrived

Mat Collishaw

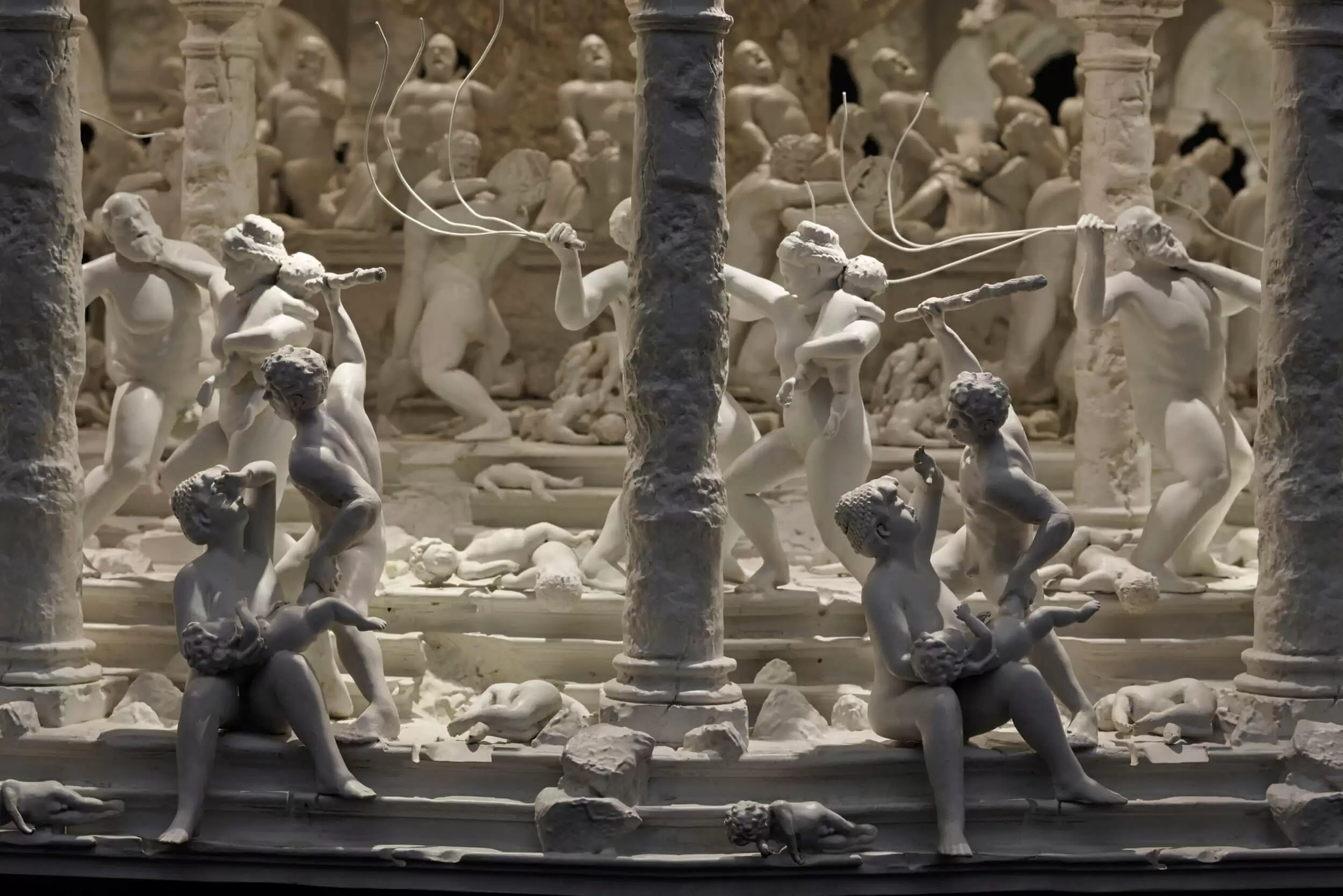

Yet beneath the beguiling veneer of his work lies Collishaw’s ongoing exploration of life’s transience, longing, and the human condition, which echoes throughout his drawings, paintings and intimate depictions of flora and fauna plagued by sexual infections, to polished sculptures where wires and circuit boards converge in harmony, coming alive during data feeds. In one of his most haunting pieces, “All Things Fall“, Collishaw’s portrayal of the biblical Massacre of the Innocents, an intriguing Zeotrope, becomes more graphic and soul-piercing as it rotates, an artistic masterpiece capable of stirring even the most apathetic parts of one’s psyche.

Collishaw’s contributions to the world of art have been significant for nearly four decades, marked by impressive solo shows and involvement in international group exhibitions. Garnering acclaim for his evocative expression from art lovers, connoisseurs, and experts has solidified him as a renowned artist. His current exhibition at London’s Bomb Factory, “All Things Fall“, explores the ominous perspective of social media and the potentially harmful way we perceive the world through these platforms conveyed through diverse mediums, including animatronics, Zeotropes and raw painting.

Collishaw’s works possess an undeniable appeal. Within his domain, the inescapable twist of beauty and dread harmoniously interlaces with artistic ingenuity, cultivating an atmosphere that nurtures our senses, bringing into question the way we see things—elevates the conversation to an art form in itself—a poignant reflection of our complex and ever-changing world.

I had the privilege of catching up with the creative maven to learn about his practice, his creative process, and what’s next for him.

Mat! How are you doing? Thank you for taking the time to speak with us. Can you please introduce yourself to those who do not know you?

Mat Collishaw: My name is Mat Collishaw and I’m a visual artist. I exhibit in galleries and museums and I make work in a wide range of media. Generally, depending on the idea that I’ve got, I try to find the best medium for the idea that I’m trying to deal with.

You’ve been a practising artist for nearly four decades. Can you tell us how you started in arts and how art has played a role in your life?

Mat Collishaw: I didn’t think I was going to be doing it for so long. Originally, I wanted to be a soldier. Then I wanted to be a footballer and then I wanted to be in a band and play music. And I started to realise that I wasn’t good at any of these things. I couldn’t do any of them very well.

But what I was doing obsessively is drawing them all. I like drawing battles, drawing football games and then drawing guitars and that kind of stuff. And I thought well, ok, I’m getting pretty good at this drawing thing. It’s the only that I can do well. And then of course you have to make a decision about which discipline to focus on. You could potentially become a graphic designer an industrial designer, a textiles designer, or whatever.

I did a foundation course at Trent Polytechnic and I knew instinctively that Fine Art was going to be my choice, but I didn’t even really know what it was. I initially thought it was just very finely drawn lines. I vaguely understood that it was about ideas, and dealing with ideas through using images and sculptures and this made a powerful impression on me.

I think it was because I was a quite shy. I find it difficult to communicate with people and art was an alternative form of communication where you could create something and then leave the room. People could then come and look at what you’ve made and it’s as if you’re having a conversation with that person through this thing that you’ve made. So it was a way of bridging that gap between me and the world. This has now ironically led me towards doing more interviews and conversations than I wouldn’t have done if I hadn’t started making this stuff in the first place.

You studied at Goldsmiths University with several other artists, including yourself, who would go on to play a significant role in shaping British art. Can we discuss your areas of interest during your time at Goldsmiths and examine whether your education there played a role in your artistic growth and contributed to shaping you as an artist?

Mat Collishaw: Right. Yeah. I don’t know how much you know about it but it was quite a brutal college. I don’t know if it’s still the same now. They didn’t give you anything to do. There’s no agenda, no plan. So you get there and they say “OK, get on with it.” You think, “What am I going to do? What am I interested in? Am I good at painting? Should I be doing photography? What about sculpture and filmmaking?” All the options are intimidating.

You have to slowly discover and question what your specific interests are. I went through a lot of different experimental periods during the first year at Goldsmiths. Because I was pretty good at good at drawing, I could craft things fairly well but it wasn’t enough. For example, I would work on a smouldering, sensual portrait of a heavily pruned local tree in charcoal and conté crayon. One of my tutors just said, “Yeah, it’s ok but does it make a difference to you that the tree you’ve drawn is growing in the inner-city through concrete, rather than in the green fields of the countryside?” It’s something I had never considered. So I thought maybe I should be thinking of these kind of things.

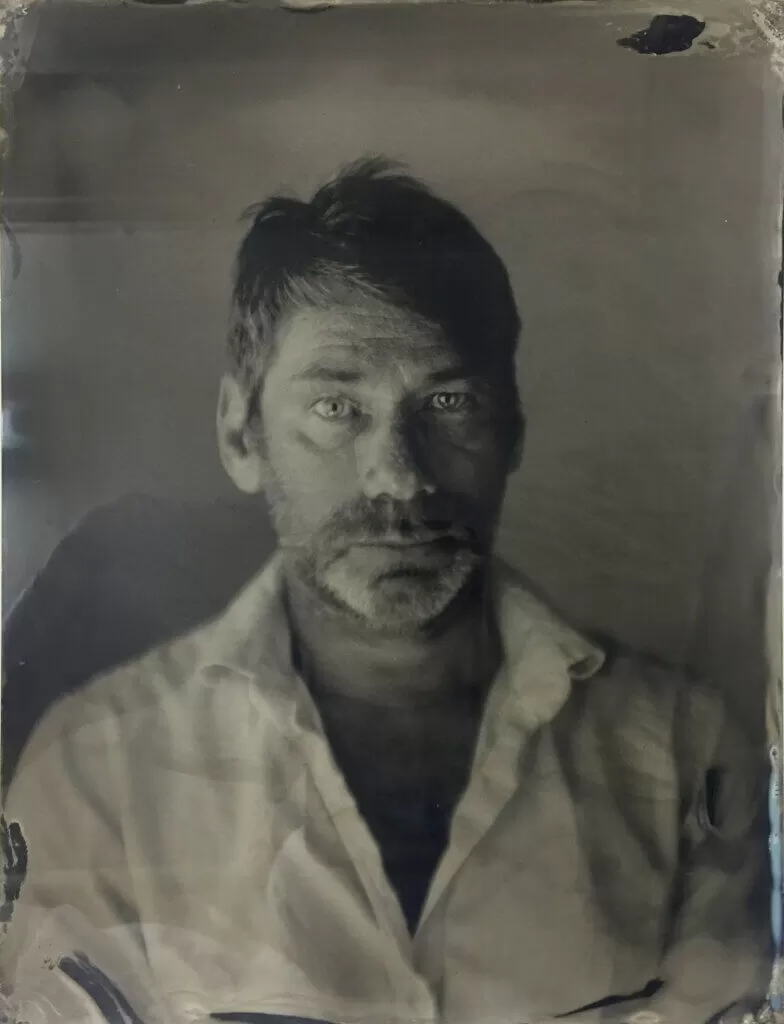

Image courtesy of Mat Collishaw ©Mat Collinshaw

One of the tutors would give me a tutorial after I had been making work for several months and they would say, “Hmm.. interesting, I’m quite intrigued by that thing over there.” They were pointing to a scrunched up Camel cigarette packet on the floor and they considered it sculpturally more interesting than anything I’ve been making. It sounds like they were being silly or being facetious. But I think they were saying that that packet had a cultural/sculptural significance because you could read it semiotically. It was a ubiquitous, omnipresent cigarette pack, the pack was empty, it was discarded, it was crushed and neglected, useless.

However, every facet of it was readable and decodable. Sculpturally it was interesting because you could read it’s significance, and that is what an artist should be paying attention to. Pay attention to the smallest detail because it’s all information that as human we are responding to all the time, generally unconsciously. Goldsmiths taught me that a neglected fag packet could be as interesting as Rodin sculpture because aesthetics and ideas shouldn’t be academic, art should be a means of invigorating our responses to all experiences however mundane.

I think the first significant thing I started doing was to stop making the drawings and find photographs in books and magazines and then try to do something with these found images.

I started working with medical pathology books and pornographic images, visuals that were heavily loaded and where there was a charge to the image. There was a lot of quite formal art exhibitions on at the time, artwork that were concerned with artistic concerns, things that the general public couldn’t really engage with without reading a Hell of a lot of text.

I wanted to work with things that people couldn’t be indifferent to, things they couldn’t just walk up to and look at and walk away from. Something that has this powerful charge to it. That led me to creating the first real work I made which was the Bullet Hole which was a photograph of a wound in the top of a guy’s head which I blew up and installed in a light box. It was an 8 feet by 12 feet image, larger than you when you stood in front of it. It was like a backlit advertising billboard with this horrific image of primal violence.

J.G. Ballard’s Atrocity Exhibition, was particularly influential at the time and still is. In this book he’s writing about the end of the 20th century and our dependence on machines, car, planes, all the metallic, mechanical, seemingly superficial entities that we embrace and interact with and the emotional detachment this fast-paced impersonal world spawns. An unhealthily but not abnormal obsession with the fascination with celebrity and violence.

I was trying to make it emotionally charged art in this emotionally detached age that we are living in.

Your work practice often incorporates historical art references, reimagining them through a contemporary lens. How do you select these historical pieces, and what do you hope to achieve by presenting them in a new context?

Mat Collishaw: I think as an artist, you always want to try and experiment to find new ground, and one way of doing it is using new materials, medium, techniques, things that have only just arrived, things like virtual reality or certain animatronic techniques. But I think if you use these techniques purely or their own sakes it’s not so interesting, I try to anchor those modern technologies with something historical so that I can bridge the gap between what happened in the past and where we’re going to in the future.

It’s more exciting to see things that have happened historically and mediate it using technology. When virtual reality became relatively cheap about seven years ago and we could create our own content I thought, I’m a visual artist and working with lots of different visual mediums, I’ve should attempt working with this game changing media. But I couldn’t really find anything that was that compelling to me as a subject matter.

Then by chance I was involved in a chat about the first ever exhibition of photography which happened in1839, the public saw, for the first time, a revolutionary new media, a new method of making visual documents of the world. These muddy little images became the medium that spawned all the other image-based technologies that came after this innovation.

I thought if I recreate this room where people had first experienced this exhibition of cutting-edge photography in 1839, and contemporary visitors engage as though they’re looking at an exhibition from 1839, but they’re actually looking through the lens of this new modern media, virtual reality. Then I can link these innovations.

I then read that the exhibition in 1839 was under threat by demonstrators. This largely working class movement were protesting because they were losing jobs through industrialisation, work was becoming mechanised. The protestors had no representation in parliament, no vote. In 1839 they were outside on the street near the exhibition, burning buildings, smashing windows. Demonstrators were arrested, hanged or sent to inhumane prisons in the colonies. I included an angry mob of demonstrators outside the window in the Threshold installation to offset the triumph of innovation and engineering exhibited in the 1839 exhibition.

There is a parallel with what was happening in the industrial revolution and what is happening with digital technology now. It’s possible that this technological revolution is going to take a lot more jobs than the industrial revolution. AI is taking so many jobs particularly, routine jobs, but it’s going to be a whole lot more. It’s been said that as humans we have two assets. The ability to work manually and the ability to think. The industrial revolution removed the need for for manual labour, if the digital revolution removes the need for human thought, what have we left to give?

The invention photography in 1839, was wonderful, modern digital technology is awesome, but what are the social consequences?

Throughout your works, you uniquely balance the grotesque and the beautiful, which often evoke potent responses. Can we delve into your creative process from concept to finished piece?

Mat Collishaw: That’s a good question. I think that we are disturbingly vulnerable to being manipulated by visual stimulation. Visually seductive things, whether it’s a flower or a nice car, a woman or a man. Most things can be embellished. The design and colour of a car, or facial makeup, the kind of clothes we are wearing. All these components are forms of manipulation which we can use or which could potentially seduce us. This weakness for attractive, recognisable patterns can be dangerous and toxic.

Flowers for example, are beautiful, seductive species, but they’re fundamentally breeding machines. All they are compelled do is to attract insects or birds using their attractive shape and colour, using their perfume to seduce a bird or an insect. A lot of flowers use visual mimicry, orchids in particularly. Male wasps mistakenly assume they are gravitating towards a female wasp to mate with, but it is actually a pattern the orchid displays which designed to look like a female wasp. Inadvertently, the wasp then propagates this flower. These little flowers are beautiful and seductive but they are essentially just predatory breeding machines, that just need to survive and propagate their species.

This phenomena of deception and manipulation occurs in multiple incarnations. I thought as a visual artist, it’s something I should be aware of and try to work with. It’s apparent in religious iconography, beautiful churches with beautiful architecture, iconic paintings on the ceilings and walls. It’s invested in convincing us to believe in this particular religion, ‘come in, serve our God’.

There are many examples in political propaganda; paintings of kings and emperors, portraits saying, “Look at me. Look how important and glamorous I am,”. Political propaganda which propagates disinformation for a more specific agenda. Convincing us to believe certain things, to distrust the immigrant, fight a certain war etc.

Then there is commercial advertising, persuading us to buy this car, buy that milkshake. They’re all using these visual mechanisms to convince us to behave in a certain way.

I’m a visual artist and I operate in a visual world. I love making things with involve, composition; line, colour, lighting etc. But I’m also aware that there’s an element of duplicity going on and these components can used for malevolent ends. I try to reflect that in my work by making things that are beautiful but then they’re also kind of repulsive when you get closer up. I made flowers that from a distance look quite nice and when you get a closer view, have these syphilitic sexual disease. It’s not a new observation, writers like Baudelaire and J.K. Huysmans write about it, decadence and decay.

Continuing from that question, how do you find this delicate balance and decide when a piece has achieved it?

Mat Collishaw: That’s very difficult but good question because the temptation is to overwork something. You develop an idea, you refine it and you refine it until there’s nothing left of it. There’s no life left in it. I think it’s important to leave something in there that’s raw. So I don’t know if I ever succeeded in doing that, but it’s something I’m aware of. It is something I constantly struggled with.

I heard a story about when Quincy Jones was producing Michael Jackson and everyone went home for the day Michael was still in the studio. He was in there all night just putting little trills on there and little frills getting everything in the mix, making it really complex. Quincy Jones walked in and said, “Michael, come on. Sometimes you just got to step back a bit, you got to leave some room for God to come in and do His work.”

I think you have to leave some space, so that when people come in to experience the work, they can project their own experiences and thoughts and feelings on to it. It’s not exclusively one thing. You can look at it from different perspectives and the work refracts ideas or thoughts in a different ways. Different people can have different responses to the work.

That is an ongoing struggle for me, because every work is quite different, it depends on the artwork I’m making, because every artwork is different and some things need to be more refined than others.

One of the sculptures in the exhibition in Marylebone Road is a robot which took a long time to build, to design, to refine, and to build and to polish so it looks kind of like a squeaky, clean, modern, and very kind of intensive production. And the contrast to that in the same exhibition right next to them, I have these paintings of like raw linen and they’re not primed. It’s just like raw, like sandy-coloured linen with just monochromatic primal image on them. It’s rough, basic and primal. Oil on unprimed linen.

Your exhibition, ‘All Things Fall,’ at The Bomb Factory Art Foundation will showcase two never-before-seen works, ‘Insilico’ and the ‘Palantir’ series of paintings, along with the debut of your large scale zoetrope sculpture, ‘All Things Fall,’ in London. Could you share more about the exhibition’s importance and provide a glimpse of what visitors can anticipate experiencing?

Mat Collishaw: OK. Yeah, sure. Some of these works are a couple of years old now, works I developed during COVID when everything went quiet outside, planes stopped, transport stopped, all the shops were closed, everyone went indoors, and it all appeared to fire up on social media. On Twitter and Instagram, there were a lot of people calling people out, shutting people down, cancelling people, a lot of aggression going on there. People were attacking each other. And I thought, well, this is interesting.

Obviously, it had been going on before but I think the intensity escalated. I don’t think it’s solely the responsibility of social media. I think it’s something within us, within human nature. Anger stimulates adrenaline which develops rapidly into a feedback loop. It’s intoxicating.

I started working on paintings which were animals, predators, and prey. There were deer on the one side and then wolves and coyotes on the other side, hunter and hunted.

I collected a lot of night vision images where the eyes of the animals glow in the dark. Hunter and hunted see each other using their weirdly high tech glowing eyes, a primal night vision facility. There’s this kind of strange remote relationship in the dark going on between the predator and its prey.

I thought it’s not dissimilar to what’s going on with our phones like all these conflicts going on remotely. It’s not face to face. It’s using digital devices but it’s across the world or across the city or across the country. I decided I wanted to make the animals in the night vison photographs ghost-like creatures, appearing out of nowhere. Spectres only discernible in the adversarial world of nocturnal combat.

So I spent a lot of time refining the technique, using raw canvas and preparing it so I could make these ghostly images of predators and prey.

I thought I should have a sculpture to accompany them and that’s when I came up with this idea of building the Stag and having a Stag struggle to stay up, its movements dictated by a live Twitter feed that was following the most abused person on Twitter. An interesting idea but in reality a was a lot more complicated and challenging than I’d imagined.

When the exhibition space became available about seven months ago, I thought, ok, now, we’ve got to build the Stag. The paintings were all ready to go. Adam my engineer and I had been designing this Stag for a couple of years. It was a very complicated piece of engineering. I’ve also been working with data analysts. Sentiment analysts or a hate speech analysts, people whose job is to go online and analyse text for the emotions and determine what is anger, or sadness, or whatever. Their job was to track who is trending on Twitter negatively and then analyse their feed and rate their incoming tweets. We then feed that rating to the Stag and the Stag responds with corresponding levels of distress.

The software will then search for the next person because it’s working live so there’s always another person who is going to be the next most abused person on Twitter.

Another artwork in this exhibition is The Machine Zone, six small animatronic sculptures based on the psychological experiments of B. F. Skinner and the things he learned in behavioural experiments that were then used by designers at Facebook, Twitter and Instagram in order to capture our attention and keep it locked in to our devices. Things he learned during these experiment are chilling, basically that we can be programmed to behave in certain ways and that we are highly vulnerable to manipulation. The little pigeons in these modular experiments pecking on these buttons reminded me of everyone on number 36 bus, pecking on their phones, all in this like grid-like format. The ghosts of these experiments lives on in the phones we carry in our pockets.

Another work in this show is a zoetrope, a recreation of the massacre of the innocents when Herod sent his men to kill all the male infants under the age of two. It’s a work that attempts to reflect on the unsavoury but familiar trope of suffering sacrificed for the sake of spectacle. It’s a carousel of cruelty, an animated orgy of violence where I tried to make something about how violence is used as entertainment; it’s on the news, it’s on YouTube, It’s in video games. It’s prevalent everywhere and some of us seem to be addicted to watching and enjoying images and films, experiences of violence on our TVs and smartphones and laptops, and etc.

So that’s the show basically. It’s the dark lens of social media, the toxic experience of the world through these potentially dangerous devices. Hopefully done in a way that’s accessible, interesting, and engaging. It doesn’t attempt to be preachy or to – I’m not against Twitter or Instagram per se.. I’m a sucker for new technology. But I think we have to be wary because there are significant dangers.

What’s next for Mat Collishaw?

Mat Collishaw: I am doing an exhibition in Kew Gardens in London in October and there’s going to be quite a lot of work in there. All he works have botanical themes, trees or flowers or birds and things that you might see in Kew Gardens.

I will have a couple of new works in there. I’ve been making some work with artificial intelligence, as has half of the world it seems. And in these, I’m making work with flowers and it’s something that I talked about earlier, which is the way that the flowers use mimicry, pretending to look like wasps and the wasps come in and inadvertently procreate the flowers. So I feed instructions into the AI, and the idea is that the AI is generating things in a blind way. It doesn’t really know what it’s doing. It’s not conscience. It’s not sentient. It’s just drawing stuff from online and then spitting it out. And these flowers evolve in a similar way. Evolution is blind. It doesn’t really know where it’s going. It stumbles on what works, and what doesn’t work doesn’t survive.

And I’m also doing exhibitions in Istanbul, Valencia, Milan. I’m also excited about this film I’ve made which accompanies live performances of Fauré’s Requiem. We are bringing that to the Barbican in London in November. I’ve been performing it in several different places around the world. So far, we performed it in Germany, in Antwerp, Belgium, in Moscow, Paris, and Hong Kong, Denmark, Sweden and Tasmania.

We mix the film I’ve created live with the orchestra and choir, approx 140 performers in total, the sound is extremely powerful.

We project on a large screen behind or over the heads of the orchestra. The film was created in the pandemic period. It features the practice of sky burial, which is what happens in Tibet where they feed their dead to vultures. The vultures come down and eat the bodies and the dead go up to heaven in the bellies of vultures rather than in the arms of angels. There are several other threads woven into the in the film.

I’m also still live on my Heterosis flower project, which I don’t know if you’ve seen. It’s an online thing. It’s a collaboration with Danil Krivoruchko on the OG.Art platform, it’s a collection of digital flowers NFTs. You can buy a flower and you can hybrid your flower to another flower to adopt properties of that other flower. And then you can try to make your flower more beautiful and more rare and all the flowers collectively are viewable in a kind of abandoned and neglected recreation of London’s National Gallery as it may look if the humanity had disappeared and organic life has taken over.

Lastly, what does art mean to you?

Mat Collishaw: It means a lot to me. It’s great, and I still love it as much as I used to 30 years ago. You can walk into a gallery and see something somebody has made as a response to living in the world. They’ve experienced suffering, and joy. They’re familiar with horror and excitement and all the emotions everybody feels, and you can see it, and you can interpret it for yourself in whatever way. That’s a very special thing. And the way that all artists see other artists’ artwork and are influenced and inspired by it, it is this network of ideas, all of this communication between human beings is very special.

For me art it has got to be about the human condition, about us struggling to live and everything that we go through. And that’s what I try to put in the works I make. All the confusion, horror, beauty, and all of those things are what I try to put in my work.

I’m not so interested in just art, just for art’s sake, like wallpaper that you can put on the wall. I’m not into art; that’s just propaganda that’s just saying, “This is wrong! and This is right!” I think for the art. It should make people question things rather than deliver a sermon. It should be a mirror, not a hammer. It should try to open people’s ideas up to ambiguity and raise questions rather than give answers.

https://www.instagram.com/matcollishawstudio/

©2023 Mat Collishaw