Bowman Sculpture Gallery is the foremost gallery in the world for sculpture by Auguste Rodin, and is situated in the prestigious Duke Street, St James’s, an area renowned for blue-chip art galleries. The gallery’s young director Mica Bowman, who is rapidly establishing a reputation as a pioneering young curator with an eager eye for young talent, had the idea for a Graduate sculptor exhibition.

Mica Bowman and Bowman Sculpture Head of Sales Daniel Pereira visited the graduate shows at London’s leading art institutions including Central St Martins, City and Guilds, Royal College of Art and SLADE, and selected 13 young artists for the graduate exhibition.

The featured artists represent a diverse range of cultures, genres and sculptural techniques, originating from as far afield as Bahrain, China, Iran and the USA. The Graduate Show at Bowman Sculpture spotlights some of the most promising talent in the world of sculpture and features artists who are pushing the boundaries of sculpture and working in a variety of mediums, as well as those who are reimagining or reinventing traditional methods of sculpture.

Mica Bowman, Director, Bowman Sculpture Gallery explains: “I believe it’s essential to shine a spotlight on artists who have consistently showcased their work and made significant strides in the art world over the past few years. Their perseverance and success speak to the strength of their talent and vision. The more we invest in these rising stars by providing opportunities for exposure and recognition, the more we contribute to a richer, more diverse cultural landscape for both artists and audiences alike.”

As the Graduate Show opens at Bowman Sculpture in Mayfair, I spoke with artists Lydia Smith, Rufus Martin, Cami Brownhill, Caroline Williams, YeYe, Harrison Lambert, Alex Ford, Naroul, Harmony-Cree Morgan, Isis Bird and Zayn Qahntani about their process and inspirations.

The Graduate Show is at Bowman Sculpture until 22nd November, 2024.

Lydia Smith

Lee Sharrock: As a next-generation sculptor how would you say you are pushing the boundaries of traditional sculpture?

Lydia Smith: I see my sculpture practice as a conversation between dimensions. While I begin by shaping clay in three dimensions, each piece undergoes a transformation through digital scanning, revealing its unique DNA blueprint. These pixelated scans act as a digital ‘still life,’ preserving the essence of each sculpture in a new form. Each digital blueprint then inspires another physical artwork, establishing a lineage where every piece is a part of an ongoing ancestry, connected through a shared creative bloodline.

Lee Sharrock: Can you summarise in a few sentences the inspiration behind your work and the process of creating it?

Lydia Smith: The inspiration behind my work centres on people and human connection. Through a research-based practice, I delve into subjects like technology, science, spirituality, and ancient history, allowing these themes to infuse my creative process. Sculpting in clay becomes a meditative act; as I enter a flow state, the research I’ve absorbed intuitively channels into the form. I let go of any preconceived design, allowing the piece to emerge naturally, guided by the resonance of my studies and the energy of the moment.

Rufus Martin

Lee Sharrock: As a next-generation sculptor how would you say you are pushing the boundaries of traditional sculpture?

Rufus Martin: Traditional sculpture has been an enormous influence for me; we are after all standing on the shoulders of giants. Rodin, Rosso, Claudel, Michelangelo are titanic figures of emotive, excellently composed, beautiful figurative sculpture, and provide an incredible foundation to learn from and build.

Like them, I work figuratively but I prioritise the expressive mark in and of its own right. They are vital for the final feeling of the work; the sum of the marks working together to describe something greater. Within the boundaries of the marks in clay, or stone, or wax lies the emotive power of both the artist and their creation, allowing for a dynamic dialogue that connects past traditions with present expression.

Can you summarise in a few sentences the inspiration behind your work and the process of creating it?

Rufus Martin: I draw inspiration from monumental cultural works, such as Milton’s Paradise Lost, on which my bust of Lucifer was based, as well as the natural beauty of contemporary individuals. My creative process is quick and raw, allowing me to capture the unique character of each subject through expressive marks. Typically, I complete the initial clay work in 4 to 12 hours, before casting it into bronze.

Cami Brownhill

Lee Sharrock: As a next-generation sculptor how would you say you are pushing the boundaries of traditional sculpture?

Cami Brownhill: I am trying to push the boundary of the abstract figure within sculpture to create unique portrayals of emotions and memories in ceramic form through creating intensely personal designs. I would say that my take on automatism to create works that present my life in this current climate means I am naturally creating sculptures that evolve with me. My art intentionally shows horror and the potential grotesque which allows my work to be unrestricted by conventions. I feel that my style of sculptural heads is forcing an acknowledgement of distress that viewers try to avoid and at the same time challenging the idea of the beauty behind craftsmanship.

Can you summarise in a few sentences the inspiration behind your work and the process of creating it?

Cami Brownhill: My work is autobiographical that presents my continuing journey of being trans and the current social climate. Taking influence from artists I admire such as Berlinde de Bruyckere and Otto Dix and with modern writing by James Tynion IV and the horror genre I aim to create impactful works. My new sculptures are adapted from unintentional drawings which reflect a memory or current emotional stage. The drawings are then distorted to create a sculptural form with no pre-determined visual end point. I work in ceramics and other physical forms as I find the taking up of space demands attention from the viewer.

Caroline Williams

Lee Sharrock: As a next-generation sculptor how would you say you are pushing the boundaries of traditional sculpture?

Caroline Williams: As a self-taught stone sculptor, in an era where everything can be done by machine, I am pushing the boundaries of contemporary art by returning to the source of what constitutes, for me, the essence of art. Working with stone and bronze has given me the opportunity to discover the processes and techniques that have made it possible to create masterpieces since the dawn of time. I appreciate this relationship with time and the permanence of these materials to link contemporary art to traditional sculpture.

Can you summarise in a few sentences the inspiration behind your work and the process of creating it?

Caroline Williams: My work expresses the movement of a fabric created by an invisible air current. Starting with a fabric model dipped in a mixture of PVA and water, I recreate what I call a “static movement”, a movement frozen in permanence. Inspired by the work of artists such as Bernini, Titian, Iris Van Herpen or Alexander Mc Queen, through time consuming craftsmanship, I capture and express the flickering instant where the fluidity and softness of the wind transforms an inert fabric into a living thing.

Alex Ford

Lee Sharrock: As a next-generation sculptor how would you say you are pushing the boundaries of traditional sculpture?

Alex Ford: I’m always trying to question the necessity of material truth in my art, disrupting the boundaries between the physical and digital. We seem to think of sculpture as a physical end product, so I incorporate digital processes as much as I can into the creation of each art-object. What’s the difference if someone sculpts physically with clay, or digitally on a laptop?

Can you summarise in a few sentences the inspiration behind your work and the process of creating it?

Alex Ford: My work has been described as ‘Looney Tunes meets Hieronymus Bosch!’ I’m drawn to immediacy, and so tend to utilise recognisable symbols or materials that are preloaded with meaning, combining these features with more corporeal forms to recontextualise the way we encounter ourselves, the world around us and art itself.

Yeye

Lee Sharrock: As a next-generation sculptor how would you say you are pushing the boundaries of traditional sculpture?

Yeye: My sculptures push beyond the idea of sculptures being a single object. They repeat themselves in large quantities, and they are never about a single object, but rather a group entity. Every piece is a representation or an image of a conceptual abstract entity, and this connection does not go away even when one of the pieces is singled out. Just like how people imagine a common daily object, for instance, a piece of tissue paper, they are much less likely to remember a particular piece of tissue paper they saw, but rather an imagined abstract image of a piece of tissue paper.

Can you summarise in a few sentences the inspiration behind your work and the process of creating it?

Yeye: My metal sculptures are inspired by my imagination of a stereotypical public abstract metal sculpture. I see them everywhere and I can never remember any of them in details, instead they altogether left a vague impression in my head. This ongoing impression can be deconstructed into a reproducible visual language to create individual small pieces of metal that are free to be reconstructed into any new forms. They are always perceived as undergoing the process of formation, there is no end nor beginning of the forms, thus the formless forms.

Harisson Lambert

Lee Sharrock: As a next-generation sculptor how would you say you are pushing the boundaries of traditional sculpture?

Harrison Lambert: My recent wood sculptures are crafted from recycled timber which is planed and laminated to form one solid piece of wood, which is then carved by hand. As an artist making work in our current time of ecological crisis, using salvaged materials makes sense both on an aesthetic and moral level. Our natural ecosystems are slowly but surely breaking down, and using scraps of wood found in a skip seems like a good way of talking about that ecological anxiety without contributing to the problem.

Can you summarise in a few sentences the inspiration behind your work and the process of creating it?

Harrison Lambert: My work shapes iconic symbols of nature, filtered through history and cultural contexts, into new remixed sculptural objects. My practice is largely informed by the materials- both stone and wood require a time intensive and tactile process. In its slowness, my process is reminiscent of an archaic style of art production, where craftsmanship and skill chase after an aspirational sense of mastery.

Neal Camilleri

Lee Sharrock: As a next-generation sculptor how would you say you are pushing the boundaries of traditional sculpture?

Neal Camilleri: As a sculptor, I constantly seek new methods and materials to enhance my creativity. By stepping outside my typical routines and embracing new challenges, I can uncover a realm of exciting and innovative ideas that will elevate my creative journey to new heights and expand my imaginative capabilities.

Can you summarise in a few sentences the inspiration behind your work and the process of creating it?

Neal Camilleri: My work revolves around exploring my past, present, and future, and transforming those experiences into reflective art pieces that resonate with viewers, evoking joy through sculpture. I incorporate colour and form to infuse happiness into the space.

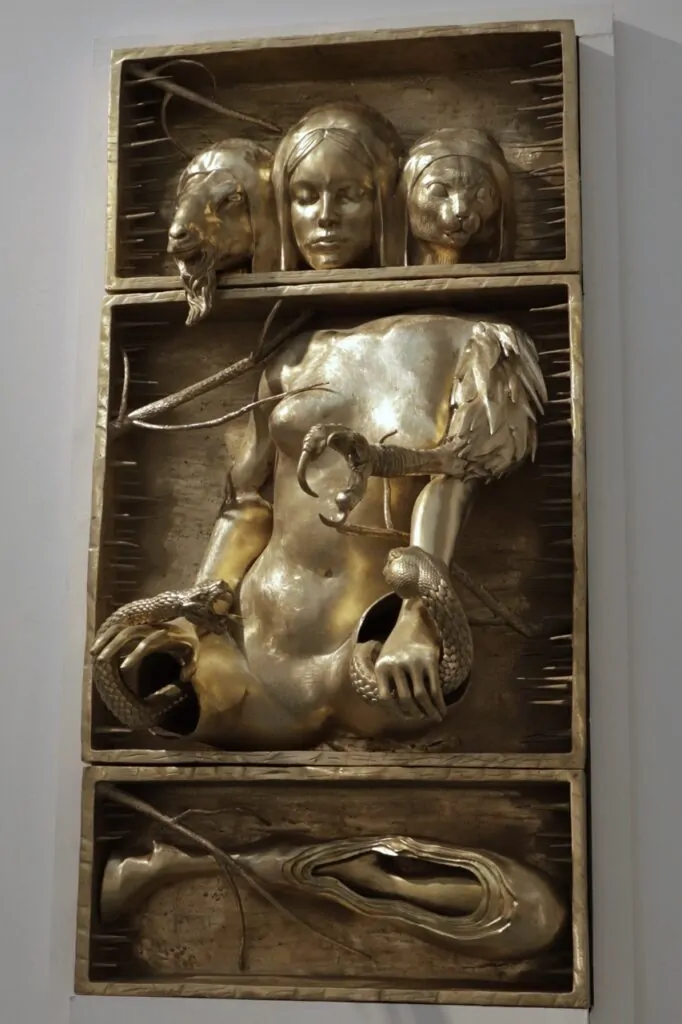

Naroul

Lee Sharrock: As a next-generation sculptor how would you say you are pushing the boundaries of traditional sculpture?

Naroul: As sociologists like Zygmunt Bauman have noted, the core of modern life has shifted from a solid to a liquid state. Over the past century, the gradual erosion of public space has rendered the traditional concept of the “monument” somewhat awkward within artistic discourse. Modern sculptors, such as Shalev-Gerz and Jochen Gerz, have successfully reimagined the narrative of public spaces through counter-monuments. However, I believe that the shift from public to personal space has become nearly irreversible. In response, our era requires a new discourse from a fresh perspective to reconnect increasingly fragmented communities. Therefore, a hidden thread in my work is the construction of monuments within “non-public spaces.” By strengthening the narrative and personal attributes of my pieces, I aim to offer new possibilities for the concept of the “monument.”

Can you summarise in a few sentences the inspiration behind your work and the process of creating it?

Naroul: The two works in this exhibition aim to explore how the identity of the “witch” has been constructed for political purposes. My interest in this topic began with Silvia Federici’s discussions on the relationship between witches and social reproduction. In my creative process, interdisciplinary literature and research methods play a significant role. For instance, in these two projects, I adopted an anthropological approach to writing and organization, integrating visual concepts with research. This approach has helped me utilize symbolic imagery within a specific framework.

Harmony-Cree Morgan

Lee Sharrock: As a next-generation sculptor how would you say you are pushing the boundaries of traditional sculpture?

Harmony-Cree Morgan: In my first year of art school and exploration with this body of work I was often told that I was not attending a design school but an art school. Alluding to furniture in my work which, is inherently anthropomorphic to me, walks a thin and fun line between object and sculpture. I like to challenge the functionality aspect of traditional sculpture that allows the viewer to interact with the pieces as they see fit. A challenge / invitation that is hinted at in some of the titles of the works.

Can you summarise in a few sentences the inspiration behind your work and the process of creating it?

Harmony-Cree Morgan: I am inspired by our daily interactions with everyday household objects that go unnoticed. Through touch and ownership, our associated memories of the chair that lived through decades of Christmas dinners or through the sleepless nights of essay writing become imbued with a sense of identity. These objects combined with live casts of my body impart with the viewer the duality of beauty and pain in gestures that I am interested in. To kneel, is not only an act of love but also is one of protest or one of punishment. I subject my own body to these gestural acts in an attempt to embody the life of an object, and so my works are born.

Zayn Qahtani

Lee Sharrock: As a next-generation sculptor how would you say you are pushing the boundaries of traditional sculpture?

Zayn Qahntani: I am in constant fascination with taking traditional methods of craft and innovating new ways of thinking about them – my sculptures often include cultural elements that link back to the island I grew up on – papers made from Bahraini date palm trees, hammered shell nacre, odes to traditional shapes in architecture and world-building.

I also think that sculpture is traditionally an exploration of the 3d object in space – a lot of my work includes elements of drawing, or sculpting on paper, or wall-based work. In these peripheries of the ‘in-between’ is where I find the most exciting opportunities to express myself with sculpture.

Can you summarise in a few sentences the inspiration behind your work and the process of creating it?

Zayn Qahntani: I am inspired by the life that I am living, and the stories I’m narrating could be my own or of the people around me. I find a lot of potency in expressing the more ‘twilight zone’ emotions – ones that we all have but keep to ourselves – such as grief, mourning, yearning, our deepest wishes and wants. I like being able to place these feelings on an altar-piece of sorts, a venerative space, so that they may be viewed in a different light or perhaps with more forgiveness.

I write a lot of poetry which is usually where my process begins – either with a few words that have been floating in the back of my mind or through something which someone has said – and will go from there. My process also includes equal amounts of pre-planning and intuition – I usually have a loose form indicative of where to start the piece, but more often that not it will take on a life of its own halfway through.

Isis Bird

Lee Sharrock: As a next-generation sculptor how would you say you are pushing the boundaries of traditional sculpture?

Isis Bird: My work comes from an immaterial space through my dreams, thoughts and poems. I think it’s amazing to see these works exist within the Bowman Sculptue space, a space embedded with so many traditional representations of sculpture.

Can you summarise in a few sentences the inspiration behind your work and the process of creating it?

Isis Bird: My recent work ‘The heart of the fool’ explores the immediacy of found objects. I was inspired by the historical and personal context that furniture holds. I have an interest in reverse-engineering neglected things: paper, chairs, objects from the street. Inspired by their previous context, I disassembled these furniture pieces, cutting, sanding and filing them to reveal the blueprints of new forms. This led to a reconfiguration process of assembling narratives.

The interplay of each connecting part and joint allows for an evolutionary lens, where both myself and the sculpture are defining our roles within the studio. Play is a key part of my process and has become intuitive. Each wooden component acts as a piece of the puzzle, guiding me towards the final sculpture which resembles an anthropomorphic object, insect-like and alive.

I’m interested in metal as a material and it appears a lot in my practice. Metal has a memory as each mark made by the artist is recorded in the material and it naturally patinas and ages over time, this reminds me of nature’s state of flux. My work ‘Orchidaceae’ is a magnified view of an orchid, a flower symbolic of sex and female genitalia. Flowers are a recurring motif in my work as a reminder of rebirth and reproduction.

An orchid plant which is found now in nearly every office space and supermarket in London but has a history of manic wealthy Victorians sending explorers to collect and discover new rare breeds of the flower. I was intrigued by this as well as the feminine form – An orchid represents perceived ideas of women’s sexuality as an equally dangerous and alluring creature.

I used reclaimed metal pieces to make this piece, using a hydro-forming technique to inflate the stem of the sculpture with high pressured water. Merging both manufactured and found pieces of metal gives this work a quality which feels both assembled and ready-made.

©2024 Bowman Sculpture Gallery