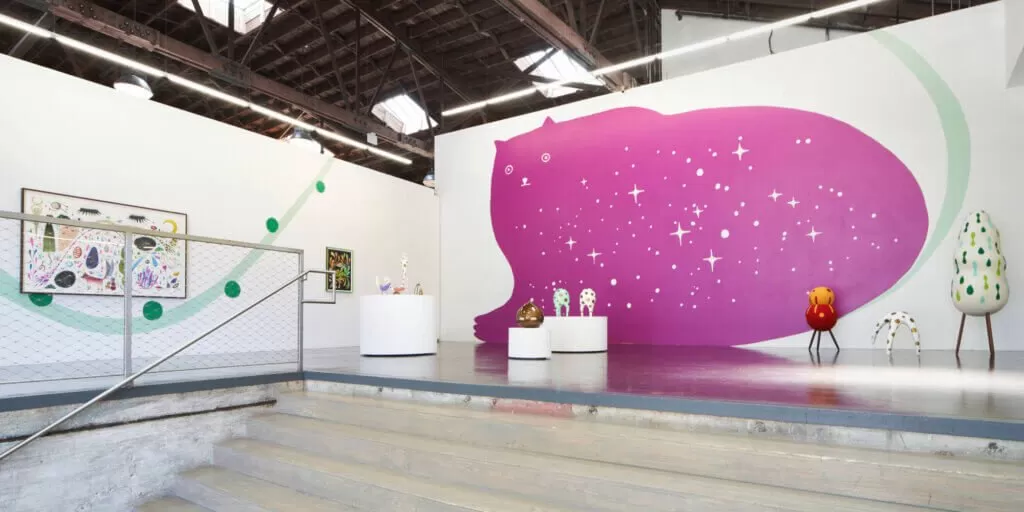

While the rest of us were hiding from the world in Lockdown, California based Japanese artist Masako Miki has been rather busy. She recently created a monumental installation of nine bronze sculptures for Uber’s new headquarters in San Francisco, hosted a stunning solo show New Mythologies at CULT Aimee Friberg Exhibitions and is about to embark on a streetscape project. The collaboration between city departments, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Yerba Buena Community Benefit District, plans to turn 800 feet of Minna and Natoma Streets into an arts corridor. Her sketches for the street furniture draw from Filipino myths, creating simplified, three-dimensional forms based on boulders, the sea, sun, moon and stars.

The Shapeshifter series started because I wanted to share my process of dealing with dilemmas and questions concerning my bicultural identity between Japan and the US.

Masako Miki

Her work is characterised by anthropomorphous felt sculptures, detailed animal portraits, bulbous bronzes and fluid watercolours which collectively explore interconnectedness and a spirituality beyond binaries. Her work is joyful and deceptively complex, drawing on multifaceted and diverse mythologies such as the Shinto concept of yōkai (shapeshifters).

Her overall oeuvre carries a positive message, championing a fluid liminality that pushes beyond the binaries culturally enforced in western society, such as secular and non-secular, animate and inanimate. Her shapeshifting entities exist between dichotomies and remain irreducible, drawing on her own experience as a Japanese immigrant woman living at the intersection of two cultures. I caught up with her in the wake of the very successful New Mythologies solo show.

Q: The past year, year and a half, has been a busy period for you, with multiple exhibitions and public art installations. Can you speak about your practice and life during the pandemic: keeping busy, making art, planning ahead?

A: It was chaotic, but I feel very lucky. For my outdoor installation at Uber’s new headquarters in Mission Bay San Francisco, we had just started to pour the foundations for nine large bronze pieces the week the city shut down. For a long while there were just giant holes in the ground where the pieces would be. Fortunately, we were far enough along where the project had to continue. So, it was interesting coordinating remotely with so many project managers on such a complex project. And I was designing four large stainless-steel sculptures for a new coastal cultural park in Shenzhen, China. They were doing all the production with their foundries, so we were able to manage that job remotely.

I was also preparing two shows in San Francisco and New York, so it was serious studio time for me — which I think benefited from the isolation. I had plenty to focus on. There was one project that just disappeared. A 30-foot bronze sculpture. We were literally a day from signing the contract, and they cancelled. It was right when everything started shutting down in March 2020. I was very anxious around that time wondering what would happen with work and my art. But I feel very grateful for those opportunities. I have two public art projects coming up this year. I cannot wait to work on these projects.

Q: Your current show, New Mythologies at CULT Aimee Friberg Exhibitions, expands an ongoing investigation of yours, one exploring your dual Japanese and American identities. Has the pandemic, the surge of AAPI hate in America, the many movements for social justice, affected the way you view this exhibition?

A: Accepting and celebrating dual/multi-cultural identities as a self-hood is one of the important ideas I express in my work. I believe we must evolve and re-invent our identities as the old identifications don’t apply to our non-binary society anymore. And our unjust social and racial inequalities are based on old mythologies and fictions that do not reflect the truth of ourselves. The last few years have been a challenging time for everyone, and, especially in the US, the real unresolved issues on race surfaced in the worst ways. As our social values need to be seriously re-examined now, it is my belief that we ask the right questions to redefine our collective identities.

Relating to my on-going research, the exhibition New Mythologies also reflected largely on life and death. I responded to tragedies caused by social injustice, racial discriminations, and the loss of my father last year. Witnessing my father’s passing made me reflect deeply on life and death and realise everything is connected at the end. I think we all experienced grief as a collective last year. The exhibition shares my process of grieving and positive narratives of empathy and resiliency needed in our current society.

Park, OH Bay, Bao’an District, Shenzen, China Photo courtesy of Shangqi Art

Q: The exhibition also furthers your exploration into the Shinto concept of Tsukumogami yōkai. For those not familiar with yōkai, could you speak a little about this rich body of Japanese folklore, and, also, what drew you to/drew you back to these mythologies?

A: The Shapeshifter series started because I wanted to share my process of dealing with dilemmas and questions concerning my bicultural identity between Japan and the US. I began to explore these questions by referencing Japanese traditions based on Shinto’s animism. Yōkai (shapeshifters) appear in my ancestral mythologies and folklore.

The simple translation of yōkai would be something like ghosts, deities, or preternatural creatures. Yōkai appear as different forms like human, animal, natural object, and man-made objects. Yōkai are not personifications of the spirit or ideas, the spirit is usually experienced through the unique physical entity. It’s a bit difficult to define who/what they are because they possess dual characteristics of being sacred and secular and animate and inanimate.

These characteristics resonated with me because they manifest the synthesis of dualities by accepting contrary characteristics. So, shapeshifters are inherently boundless in their nature as they continue shapeshifting throughout their existence. These hybrid beings can become more than one thing. Because of their unique characteristics, they do not conform to accepted identities; instead, they generate new identities. I felt these ancient yōkai characters offer interesting narratives that are relevant to our current society. In our non-binary society where multiculturalism, gender fluidity and biracial identity seem to be more the norm, our identities have become more complex than in the past.

Shapeshifters also bring non-human-centric perspectives of the universe. In Shinto animism, everything in the universe is sacred because spirituality exists within materiality. Nothing is considered insignificant; even a mundane object like a simple tool is imbued with spirit. The embodiment of this idea is a group of shapeshifters called Tsukumogami yōkai (shapeshifters of aged-discarded tools); They include a wide range of characters — from an animate iron pot to animated scriptures — and these objects have come alive after 100 years of existence. This is rooted with the Shinto idea of “Yaoyorozu no kami,” which literally translates to Eight Million Gods. It means there are a myriad of gods in this universe. The interpretation of the idea is that many deities exist because they are incomplete deities. They can only fulfil their duties as a collective.

Courtesy of CULT Aimee Friberg Exhibitions

Q: While we have been talking about a number of your ongoing interests, you have started to assert yourself in a new medium: bronze. After largely working in felted wool, what was it like making the transition to working in bronze?

A: I began to explore bronze when I worked on the Uber headquarters outdoor installation. Working with bronze has been such an interesting process, and I am learning so much about the medium. I am intrigued by its history and depth.

The process becomes collaborative with the foundry. My large felt pieces share a similar process: involving multiple elements of 3D scanning and CNC cutting to produce works. But working with bronze requires more parties to complete works. This necessitates clear communication and trust with the foundry. I feel so much possibility working with bronze in terms of the scale and placement. Bronze can be installed both indoors and outdoors and can scale up in monumental size by collaborating with master artisans and foundries. I am looking forward to working with this material in the upcoming years.

Q: New Mythologies features work in bronze, felt sculpture, and watercolor, offering different textures, depth, color, and form. How do you understand and view these materials? Do you see yourself continuing to work in these different mediums?

A: I respond to materials almost instinctively, then begin experimenting with small pieces. Exploring new materials makes sense because my work is about being able to shift and evolve by keeping idiosyncrasies.

I enjoy working with multiple materials because each one offers a unique identity. The authentic quality of each material helps to create strong narratives in the work. Watercolour’s quality ties with the idea of fluidity. The transparency of the medium shows complexity by a wide range of colour mixing and layering processes. Needle felting with wool is generally considered a craft medium. I tend to gravitate more towards craft mediums than fine art mediums. I have made a lantern series with two materials — Japanese rice paper and starch glue.

I love the simplicity and accessibility of the materials. For felt sculpture, I just need a single needle and wool felt. The wool material invites viewers with its tactile textures and bright colours. I love the transformation of these simple materials when the work is completed. With bronze, I responded to the material because of the flexibility in casting process and final finish, which can be patina-ed or painted. Bronze is a durable material for the outdoors as well.

I continue to learn and practice using materials like bronze, felt and watercolours in my work. But also, I have the privilege to collaborate with other artisans, and I get excited to work with new materials. I have been exploring wood and possibly glass fibre reinforced concrete for my upcoming public art projects next year. Sometimes projects introduce me to these new materials.

Reminding of the Universe Photo by Henrik Kam. Courtesy of the Masako

Miki and CULT Aimee Friberg Exhibitions

Q: You received a commission from Uber for an outdoor installation at their new campus in Mission Bay, San Francisco, which is just a short walk away from your CULT show. What was executing this large-scale, prominent project like for you?

A: I was beyond excited for this opportunity. It was quite an involved project due to the scale. I created nine bronze sculptures from three feet to 20 feet high. I love how everything came out, and I appreciate everyone’s enthusiasm to create something meaningful together for the community.

Collaboration with many talented professionals was one of the highlights from the project. I am grateful to everyone who made this installation possible. I also learned so much about working on large-scale installations. It is quite a process to complete this level of project. It takes a long time to plan, produce and install. Every step requires great attention, communication, and collaborative efforts. This project expanded my visual language and opened more opportunities for outdoor installations.

Q: This comes on the heels of a public art installation show you did in Shenzhen, China, in December 2020. Are you interested in working more in public, outdoor contexts?

A: Yes, I am. I enjoy the process of collaboration in public art projects. Another reason I like to work in public, outdoor contexts is accessibility. Now that I have completed a few public art projects, I started to think about how we can experience more art every day.

Public art can expand the audience in a significant manner. When art lives openly in public, people can pass by on the way to their work or taking a walk with friends and families — artwork becomes part of their everyday life experience. I think this is an important idea in our communities. Art installations can be a reminder of current issues and create dialogues for new perspectives that are relevant to our lives.

. Photo by Henrik Kam. Courtesy of the artist and CULT Aimee Friberg Exhibitions

Q: Finally, both of these shows find you moving away from the human scale to something larger than life. What has it been like extending beyond the intimate scale of so much of your previous work?

A: Being able to change in both material and scale echoes the idea of fluidity. My art emphasizes the idea of accepting dualities and continues to expand the definition of unique identity. I enjoy seeing my work expanding from miniature size to life-size and monumental scale. It shows the process of growth and evolution. It is a different way of expressing ideas. Intimacy can be experienced with a smaller scale, whereas a viewer becomes a part of the installation in a large, monumental work. I will continue to work on both scales in the future. It is not about either/or — each scale offers a unique way of connecting with viewers.

I find it interesting to create monumental outdoor sculptures that are not historical heroic figures. Many of my sculptures are discarded aged tools of shapeshifters. It is ironic that scale here creates the importance of mundane and replaceable objects. They are ordinary characters in ancient mythologies, like the ordinary people in our society. This mirrors the importance of collective efforts by the ordinary who bring extraordinary deeds to our society. Perhaps these sculptures can make ordinary people more visible.

https://www.instagram.com/masakomiki/

©2021 Masako Miki, Andrew Payter, CULT Aimee Friberg Exhibitions.

Art writer, curator and public relations specialist, focussed on platforming emerging talent across the visual culture sector. When not walking my dog in rainy East London parks, I can be found on my sofa writing articles for FAD magazine, Bricks Magazine, Art Plugged and Off the Block Magazine. Find me on Instagram @bellabonner