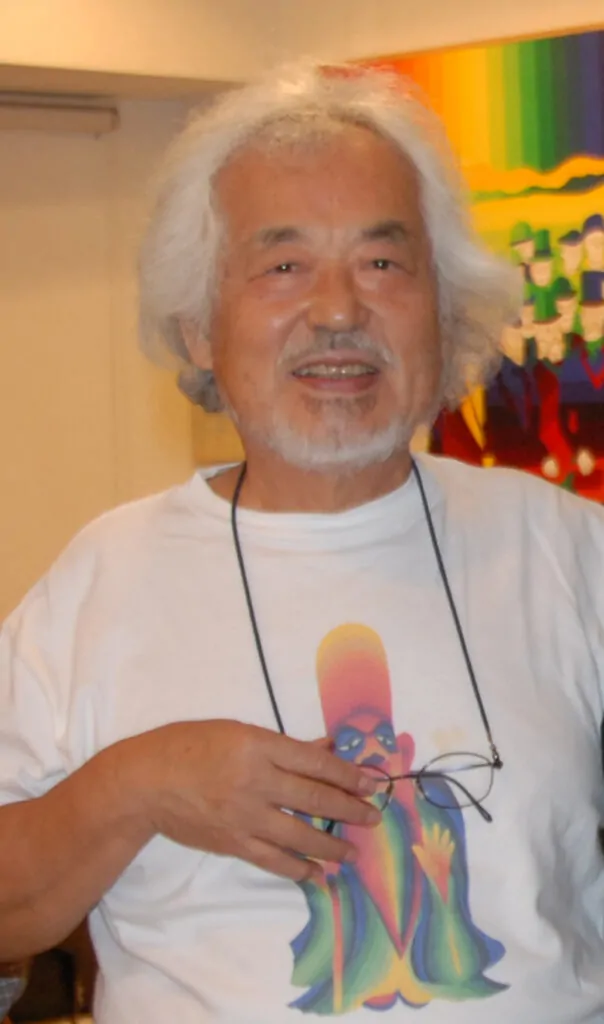

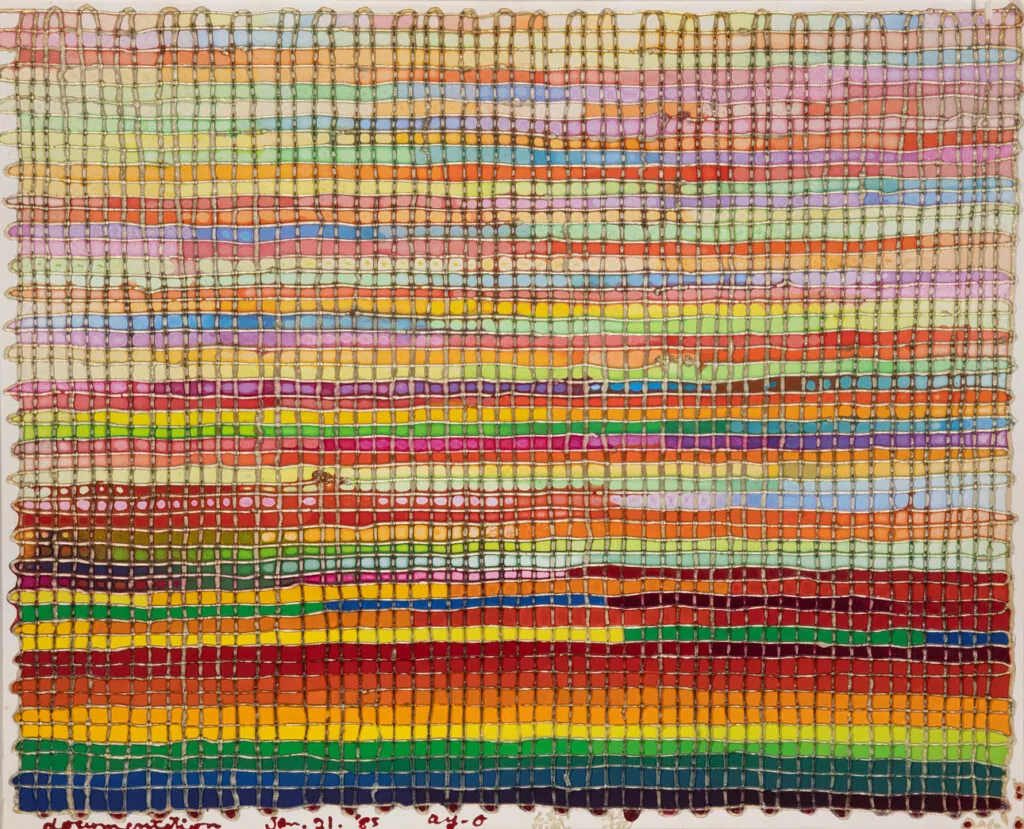

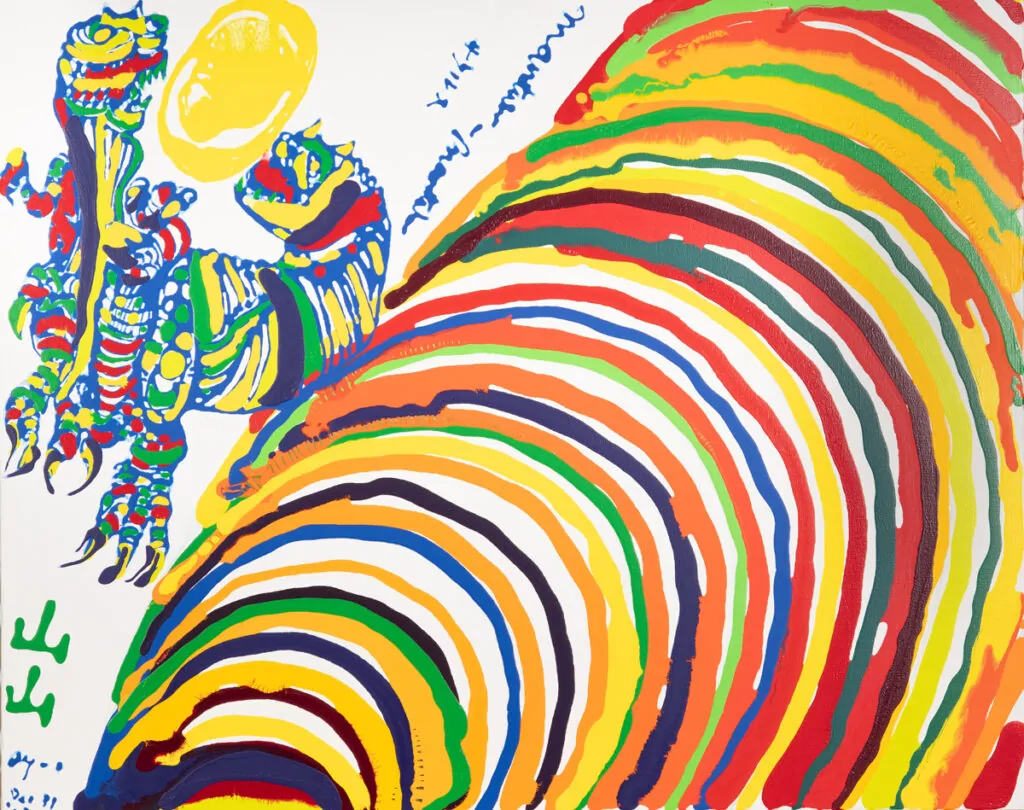

Visionary Japanese artist Ay-O, known as the “Rainbow Artist,” has captivated the world with his flamboyant command of colour for decades. A crucial member of the avant-garde Fluxus, he has engraved a legacy into the stone of art history for his playful yet conceptual engagement with colour and space.

Influenced by tactile and sensory elements, Ay-O’s early works explored texture and perception through interactive art. Born in Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan, in 1931 as Takao Iijima, Ay-O began his journey into the arts. He studied at the Department of Art at the Faculty of Education, Tokyo University of Education, setting him on the path to becoming one of Japan’s most influential artists.

(Photo: Yumi Takaishi)

Art is not something created entirely from scratch, but something that is discovered. This has always been my approach. There is always something on the other side.

Ay-O

As Ay-O studied fine art, Japan was undergoing rapid modernisation and industrialisation after World War II, which disrupted the cultural fabric of Japanese society and influenced the nation’s arts community, with many artists questioning the relevance of classical forms and seeking new ways to express themselves in this new era. This led to the formation of many artist groups, such as the Demokrato Artists Association, which aimed to explore new forms of expression.

Demokrato championed artistic freedom, encouraging its members to ditch academic rules and think outside the box. Ay-O joined the association in 1953, rubbing shoulders with artists like Ei-Q and On Kawara.

In 1955, Ay-O co-founded Jitsuzonsha (The Existentialists) with fellow artists like Masuo Ikeda. It was through this group that Ay-O’s love for printmaking took root—a medium he would continue to master for decades to come. By 1958, Ay-O was ready for a change, and where better to go than New York City? The Big Apple was a hotbed for avant-garde art, and Ay-O quickly became a link between the Japanese and American scenes.

In 1961, Yoko Ono introduced him to George Maciunas, the mastermind behind Fluxus. The group sought to break down the barriers between art, life, and what constitutes art. By 1963, he officially joined the group, collaborating with other avant-garde artists like Emmett Williams, Dick Higgins, and Nam June Paik.

The 1960s turned out to be Ay-O’s most transformative decade, and his first ‘rainbow happening’ at Carnegie Hall in 1964 was just the beginning.

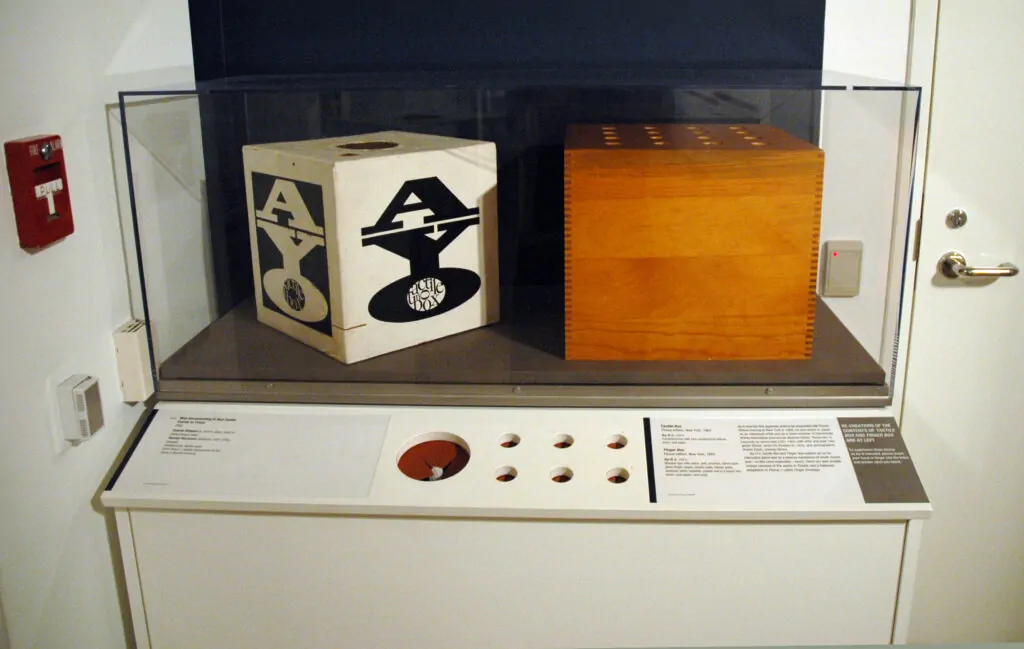

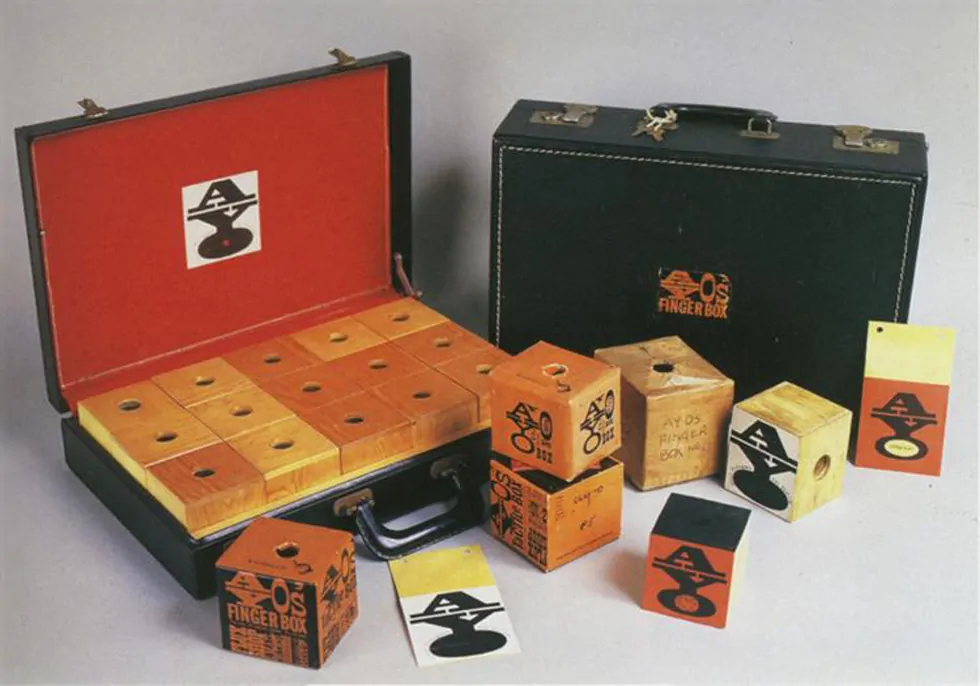

Soon, he was representing Japan at the 1966 Venice Biennale, with works that invited audiences to engage their senses in unexpected ways. His Finger Boxes series, for instance, asked people to touch and feel art without relying on their vision—a bold move that redefined sensory experience in art.

Ay-O’s rainbow dialect emerged during this time and defined much of his work going forward. He didn’t stop with prints and paintings—he brought rainbows to life in installations and sculptures, too. One of his most striking projects came in 1987 when he transformed Paris’ Eiffel Tower with his iconic rainbow colours.

Blending Eastern thought with Western avant-garde experimental energy, Ay-O’s works are more than just colourful art; it serve as a cultural bridge. Reminding us that creativity is not about reaching a destination, but about the joy of discovery. After all, art—and curiosity—know no borders, and this is what he has demonstrated for decades, inspiring countless artists across the globe.

In conjunction with Eiichi Matsuhashi, Director, Karuizawa New Art Museum we spoke with Ay-O.

Hi Ay-O, thank you for speaking with us. Please introduce yourself to those who might not be familiar with your work

Ay-O: My real name is Takao Iijima. I was born on May 19, 1931, in Ibaraki Prefecture. In 1950, at the age of 19, I entered the Department of Art at the Faculty of Education, Tokyo University of Education. I moved to the U.S. in 1958, at the age of 27. Since then, I have been creating artworks for 74 years, and I am now 93 years old.

Matsuhashi: What made you choose being an artist as your career path?

Ay-O: I became an artist because I have always enjoyed drawing since I was a boy, and I always planned to pursue a career in art. I am good at organizing things, and even as a student, I was involved in the theater club and various other activities. I love to create.

Matsuhashi: So you were already forming various groups when you were a boy. Was the idea of becoming a painter particularly special to you during the war?

Ay-O: I had that intention from the beginning; I never thought about anything else.

Matsuhashi: What is the origin of your name Ay-O as an artist?

Ay-O: I asked a friend to choose his favorite letter from the Japanese vowels: a, i, u, e, o.

Matsuhashi: So you create your own rules. Is it like a game?

Ay-O: Not at all; it was chosen seriously. It’s not playful like a game, but something earnest. I believe that finding something by entrusting it to others is what makes someone an artist. It is important that what is created organically becomes the artwork, and the artist discovers it. That’s what contemporary art is about. It’s not about creating something from scratch, but about bringing it forth from somewhere.

Matsuhashi: So, it’s about finding something. That is a very important concept in contemporary art. Surrealism also has a concept called ‘found poetry,’ and it’s amazing that you were already practicing such an idea when you were a university student.

Ay-O: Art is not something created entirely from scratch, but something that is discovered. This has always been my approach. There is always something on the other side.

Matsuhashi: It seems like your essence was captured in your introductory remarks. I’m also impressed by the fact that your methodology has remained consistent in thought from your student days to the present.

Ay-O: I believe that is what contemporary art is all about.

Matsuhashi: The fact that your artist name itself was created using the same methodology as your artworks is fascinating.

Matsuhashi: Mr. Ay-O, your career as an artist spans over 70 years. The first art group you joined was the Demokrato Artists Association. How did this period of artistic freedom and independence influence your subsequent activities? What kind of group was the Democrat?

Ay-O: The term “Demokrato” refers to democracy and freedom.

Matsuhashi: At that time, less than ten years had passed since the end of the war, and compared to today’s understanding of freedom, the desire for freedom among people back then was much more eager. This is because the previous era was wartime, during which there was no freedom.

Ay-O: In my youth, the purpose of life was to find freedom. That is the basis for everything.

Matsuhashi: There was once I asked you what kind of group was the Demokrato group, you replied that it was a very democratic group. At first, I thought that I was being somewhat misled, but upon reflection, I realized you were correct. It was a group that operated equally, without seniority or hierarchy.

Ay-O: Democrat is democracy. I like the new and want to erase the old. I aimed to remove distinctions between seniors and juniors. I actively tried to get rid of it. It’s a young person’s way of thinking, to get rid of the old things.

Matsuhashi: I think that this was made possible largely because of the group leader, Eikyuu. I think that Eikyuu was great for creating such an atmosphere of freedom. In traditional organizations and groups, there is a hierarchy of seniority and juniority, and I think it was normal that the opinions of long-standing members were valued and those of newcomers were often ignored. I have heard that veterans’ works were also considered important, while good works by young artists were not exhibited in prominent places.

Ay-O: All those things and ideas were discarded. Everyone worked together to create something different.

Matsuhashi: I believe that was Eikyuu’s philosophy.

Ay-O: Yes, it was. He was great. I respect Eikyu the most.

Matsuhashi: There were many different groups formed at the time, but Demokrato was truly a free group. It’s regrettable that it disbanded so early. I believe that the spirit of freedom is fundamental to your work and has continued since then. The artistic freedom of your subsequent stance of creating new experimental works and creating things that had never existed before was cultivated during this period. Additionally, I think Eikyuu was significantly influenced by pre-war Surrealist artists. Some of his photography, for example, is quite similar to Man Ray’s style.

Ay-O: I am influenced by Eikyuu.

Matsuhashi: In this sense, it can be considered that the influence was passed down from generation to generation. It is also an interesting fact that you later met the prewar avant-garde artists such as Marcel Duchamp directly after you went to the U.S.

Matsuhashi: Your work has continued to evolve throughout the years. This evolution became particularly noticeable after your arrival in the United States, and more so after you went to New York and joined the Fluxus group. How did these various experiences during the 1960s period create the multifaceted approach to your art over the following years and how did they influence your subsequent artistic direction?

Matsuhashi: You went to New York in 1958, when the action painting was at its peak. But since you pursued your own path distinct from such trends, I think you must have had a very difficult time financially.

Ay-O: From the beginning, I had no intention of joining the art group. I thought what I was doing was the most modern, so I had no plans to create abstract works. I can’t associate with old things.

Matsuhashi: When you first went to America, you painted in several styles. First, you created abstract paintings and then painted X over them to negate them, or made holes in canvas, and so on. Wasn’t this a period of experimentation when you were exploring various things?

Ay-O: What I wanted to express could not be done with the old materials. With old materials, you get old expressions. New expression required new materials, such as metals that I had not used before.

I don’t know if that is a good thing or a bad thing. No one recognized anything made with new materials as art. At that time, they were not recognized as art. Also, there is an accumulation of many works (studies) under these works.

Matsuhashi: So it was the result of a lot of trial and error. New art attracts the attention of new artists. After that, many young artists began to visit your studio. New ideas, new materials, and new works of art attracted new artists. Some of them would later become members of the Fluxus group. Works like Tea House and HYDRA, created in the early 1960s, are unprecedented. The idea that you could go inside the work and appreciate it is very innovative.

Ay-O: It is called Environmental Art.

227.5 x 82cm

Matsuhashi: Various people began to gather, and interactions became more active.

Ay-O: Yes, that is right. I am good at organizing things.

Matsuhashi: In the process, you began to interact with George Maciunas, the founder of Fluxus. As I recall, he was scheduled to have a solo exhibition at the AG Gallery, but the funds got jammed and he left for Europe, so the exhibition could not take place. A few years later, after things had settled down, Maciunas returned to New York and Fluxus began its activities.

Ay-O: I think he lived above or next to my room. Everyone around me started to gather.

Matsuhashi: This may be in a way the same as what you were doing in Demokrato. It was a free gathering with no hierarchy at all, wasn’t it?

Ay-O: There was no hierarchy. We had a lot of things together, and they belonged to no one. We did many things. George was doing George. We just picked up new things. It was not like learning, we were just doing it for fun.

Matsuhashi: So the person who found something first was the one who has recognized. The question is, how did your time in New York influence your later art? Perhaps it has always been the same. It seems to me that it still continues with the same content. Usually when you have been doing this for a long time, you pursue things like technical improvement and refinement, but I don’t think that’s what you guys are going for.

Ay-O: Yes. We have been doing only new things, not the same kind of art that someone else has been doing until now. I must have been at the bottom of the art world.

Matsuhashi: There have been many cases where something that was at the bottom of the art hierarchy suddenly became the most important one day. So I think the same thing is happening with your art.

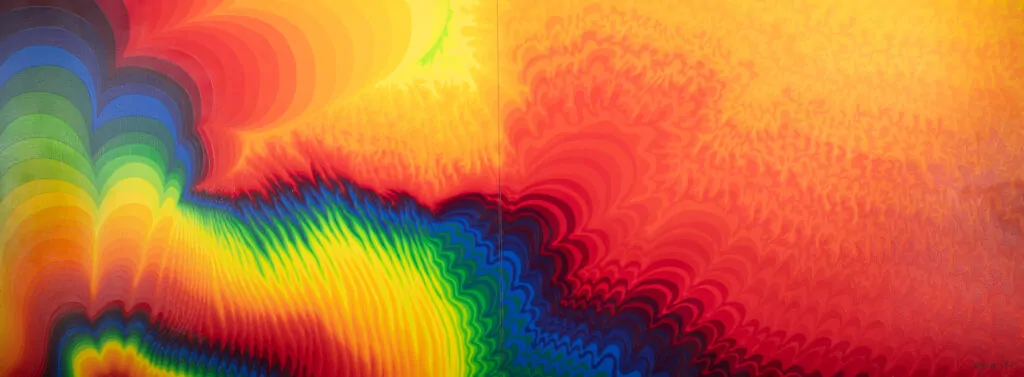

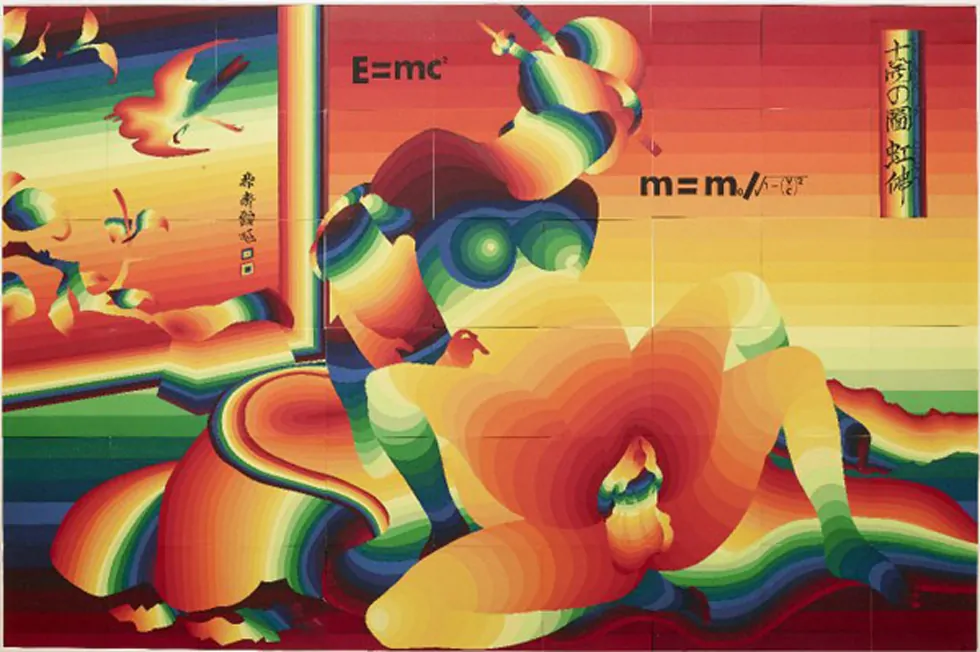

Matsuhashi: The title of your current exhibition in Hong Kong is Ay-O: Nijitsukai. (虹使い: Rainbow-charming). Can you tell us how your fascination with rainbows influences your artistic process and thinking? Rainbows are the main theme of this exhibition.

Matsuhashi: Rainbows are beautiful, but some people think that you create paintings with them because they are beautiful, but that is not how these works were created, and I think that needs to be explained in this interview.

Matsuhashi: As you have previously explained in your own writings, in creating works related to all the senses, the five senses, you created Fingerbox (tactile), Rainbow Dinner Show (taste), Perfumed Paintings (olfactory), Fluxus Orchestra (auditory), and finally, in pursuing the visual, I think you are saying that the Rainbow works were the beginning of a scientific process that systematically painted the spectrum of colors between ultraviolet and infrared, the human visible range, in sequence.

Ay-O: That’s right. That is absolutely right. I never thought of making something beautiful. I did not make rainbows because they are beautiful motifs. I never once thought of making something beautiful, and this is what I ended up doing when I pursued something interesting. I believe that there is beauty not only in beautiful things, but also in dirty things. This is what I arrived at in my pure pursuit of the visual.

Matsuhashi: It is important to understand that even if a work is beautiful because of the colors and gradations, it is merely the result, and that this style was not created with the goal of creating a beautiful work of art, but as a result of pure experimentation in painting.

Ay-O: It is always the case that something new comes out.

It is not something that you work hard to build up and create, but something that appears out of nowhere.

acrylic on canvas, 116.7 x 91 cm

Matsuhashi: I think there is a world of traditional art that is built up through accumulation. However, your art might not belong to that realm. Aspects like having a keen eye or good footwork could be important elements in your art, which may have been shocking to those who didn’t possess these qualities.

Ay-O: When you pick up a lot of different things, other people will say, “Oh, he picked up some good stuff.”

Matsuhashi: This was not possible in the old days in the art world, and I think the mainstream was to train over a long period of time.

Ay-O: It was a narrow world in those days when that was the norm.

Matsuhashi: If it were just pretty, it would be an ornament, but this is not that kind of thing.

Ay-O: Art is not limited to just beautiful things; it also exists in dirty things.

Matsuhashi: The 33rd Venice Biennale in 1966 must have been a major milestone in your career, but now that you look back on that time, how do you think this event influenced your subsequent work and direction as an artist?

Matsuhashi: Here are the magazines from the Venice Biennale and the blueprints that you made.

Ay-O: Where is this work?

(Looking at a photo of the installation work on display at the time that appeared in the magazine)

Matsuhashi: This piece is no longer here. Perhaps it was dismantled after the exhibition ended. However, there are models and blueprints here, so you can imagine the overall composition.

Ay-O: Was this exhibit created by me on site?

Matsuhashi: Probably yes. I believe that the entire exhibition plan was made by the professor at this time. The blueprint of the entire venue is here, and the teacher wrote all the configuration of the venue, including the placement of each artist.

Ay-O: I see. I forgot, but I tend to take the lead in whatever I do. I’m quick at my work, so I keep creating more and more.

Matsuhashi: I think the exhibition at the Venice Biennale made your work known to people in Europe.

Ay-O: Yes, it did. Before that, I was completely unknown in Europe.

Matsuhashi: At that time you were with Toshinobu Onosato, and Masuo Ikeda.

Ay-O: They were all new and unknown. I didn’t think that Masuo Ikeda would become that famous.

Matsuhashi: Mr. Ikeda received an award at that time. And Mr. Ay-O, you became very famous for something else. The finger box that was on display, one of which had a nail inside, and the person who experienced it injured his finger. The newspapers picked it up as news. The next day, a lot of people started coming to see that piece, and that is how the name of Mr. Ay-O became known locally at once.

Ay-O: That is a famous story.

Matsuhashi: After the Biennial your name became known worldwide and you went to the University of Kentucky. This must have brought economic stability, didn’t it?

Ay-O: Yes, it did. Until then, it had been difficult to make a living as an artist. Becoming a university teacher provided financial stability.

Matsuhashi: During this period, you created a very large work called Rainbow Tactile Room, which is a compilation of rainbow works and Fingerboxes in a 3.6m x 3.6m sized room with rainbow units and Fingerboxes. This work was also exhibited at the 1970 World Exposition in Osaka.

Ay-O: This wasn’t something that had a clear plan from the start; it developed as I continue to work on them.

Matsuhashi: I think it was created in cooperation with the students of the university at that time. Your methodology is not to create everything by yourself, but to collaborate with others by presenting a direction and having them work toward it. I think printmaking is also connected in the sense of division of labor with the printer.

Ay-O: Entrusting certain parts to others can be an interesting approach.

Matsuhashi: I feel that Mr. Ay-O, you have challenged some of the old conventions of the art world during your career. In particular, I think it is to your credit that you have raised the status of printmaking in the art world by advocating that printmaking is an art form on the same level as oil painting. What do you think about that?

Ay-O: I never consciously tried to challenge the old conventions. I don’t know about my peers, but maybe that’s what happened as I did various things.

Matsuhashi: Do you think you changed the hierarchy in the art world, where oil painting is at the top, followed by drawing and watercolor, and printmaking is below that? It has been said that you were instrumental in elevating the status of printmaking.

Ay-O: Prints were worthless in our time. They were like posters and were not considered art.

Matsuhashi: You started your career as an artist by making prints, which sold well and led to your professional debut.

Ay-O: That’s one thing, but at that time there was no one buying my paintings. The price was too high.

Ay-O: A few artists’ works were selling well, but they were out of the reach of the general public. At that time, prints were the main type of artwork I was making.

Matsuhashi: Nowadays, prints are appreciated as art, but at that time they were not art. However, there was a tradition of ukiyo-e in Japan, and there must have been a custom of buying prints.

Ay-O: That is also true. We were trying to sell prints by telling people that they were also art.

Matsuhashi: But do you think you were able to continue making them not just for the money, but because there was something appealing about them?

Ay-O: Yes, I think so. Relatively many people bought the prints I produced, which I also devised in various ways. Since many of them were the same, they were not considered art at first. Even so, I continued to sell them, saying that they were also art. There were no art galleries at that time. So prints, which were not highly regarded at first, later became the object of appreciation as art.

Matsuhashi: Nowadays, there are many galleries specializing in prints, and contemporary prints are highly regarded. I think that many of your silkscreen prints are contemporary and beautiful. They are also highly acclaimed overseas and displayed in large spaces in exhibitions.

Ay-O: That may be so.

Matsuhashi: Looking back over your career of more than 70 years as an artist, have the receptions of Mr. Ay-O’s works and activities changed as time has gone by?

Matsuhashi: Also, what aspects of your work do you think reach the hearts and minds of contemporary audiences?

Matsuhashi: I wonder if the general public recognized the activities of the early 1960s as art? Here is a picture of a Fluxus street event. Some people are watching, but did the people watching consider this art?

Matsuhashi: It looks like they were simply onlookers who gathered because they were doing something.

Ay-O: Yes, that’s right. Isn’t that still the case today?

Matsuhashi:: I don’t think people still don’t understand it, but even so, from the 1980s onward, Fluxus was reevaluated as an art form, and various museums began to take it up and introduce a variety of things to the public. Research books and publications of the time were also re-released, and objects were re-produced.

Ay-O: It was a strange thing we were doing at the time (1960s), but was it slowly being understood?

acrylic on canvas, 72.7 x 91.0cm

Matsuhashi: I think the concept of art expanded and the range of acceptable art became wider. In fact, in the 1980s, artworks were selling at a price. There were not only artworks but also various activities.

Ay-O: I remember that. However, my works were selling to some extent even in the 1960s. There were good artists, but many of them did not sell. I don’t know what it was that made them sell, but they were attractive to buyers. It was interesting that people were able to buy and sell, so that even if something was strange, there were people who would buy it, and those who bought it would begin to realize later that they had bought something strange, but it wasn’t so bad.

Matsuhashi: In the end, I think the concept of art has expanded.

Ay-O: Yes. Perhaps it was not just one piece of art, but many pieces that came out and spread out, and were recognized as such.

Matsuhashi: I think that the popularity of his works was due to the fact that many of your works are humorous and cute. I have some of your work myself, and I enjoy being in contact with your artwork.

Ay-O: Generally speaking, art is not fun. There is this idea that art has to be serious.

Matsuhashi: Yes, it is. Suffering, for example. Heavy themes are sometimes expressed.

Ay-O: We were kind of playing around.

Matsuhashi: The element of fun. Adding the concept of gags, humor, and laughter to art is something new. There are a lot of funny things in Fluxus.

Ay-O: (Looking at Robert Watts’ work in Fluxus with the weights of the various stones on them.) This is hard to weigh. I weigh them all. It takes a whole day, but I can’t do much. Everyone made so many different things.

Matsuhashi: I once read in a text that when Mr. Ay-O went to Jasper Johns’ house, you were very happy to see your finger box work on a shelf in his study. Does that mean that it was very encouraging to you that a senior artist liked your work?

Ay-O: I think so, yes.

Matsuhashi: I think it is wonderful that the artwork makes people happy.

Matsuhashi: What do you think future generations, in other words, future audiences, will think of your works and activities? How do you hope they will view your work?

Matsuhashi: How do you hope future generations will interpret your work?

Ay-O: I don’t know what the future holds. I have never thought about that. I don’t really care how they interpret my work. I want it to be seen as I want it to be seen. And I don’t know what the future holds. (Looking at the pictures of the Eiffel Tower Rainbow Project.) I think I made these things because people would see them.

Matsuhashi: So you wanted people to look at them freely.

Ay-O: I liked these things. It’s the same with big things and small things. I was doing strange things. I was thinking about all kinds of things.

Matsuhashi: You must have had many plans that never came to fruition. I once saw a drawing in your studio of a project to hang a rainbow sash from the Statue of Liberty.

Ay-O: Maybe I was thinking of something like that. I forget now.

Matsuhashi: Looking back on your career, what do you remember most? It may be difficult to pick just one, but what do you think?

Ay-O: There are many. I don’t know, there are so many things.

Matsuhashi: I think it could be a variety of people, meeting Eikyuu, meeting George Maciunas, and so on. It is probably our side of the conversation as to what we think of them.

Ay-O: There were many things that happened at that time. There are many things that left an impression on me.

Matsuhashi: Technology and the application of new technology to art — there are many pieces that are wrapped in foam rubber or that are not looking for visual pleasure or effect. There are works that take you to another world, like another dimension, but there are many forms of work that have never been done before. How does the application of new technology to art reshape traditional boundaries, and what role does this play in the future of artistic creation?

Ay-O: We are doing a lot of things with the intention of creating something strange, an odd world, a mysterious thing. However, it is not something that was created with the intention of creating something specific.

Matsuhashi: You have created many works using the new technology of the time. For example, when color copying was first introduced, you used it in your art. Similarly, when computers became available, you incorporated them into your work as well.

Ay-O: I always work with new materials and explore new dimensions. However, when creating, I don’t have a specific vision for how I want the piece to turn out or how I want to create it. After the work is completed, I might evaluate it based on the interpretations and reactions of those who see it. My process isn’t driven by expectations of how it should be done or what kind of feedback I might receive for using new techniques.

Matsuhashi: You incorporate everything, making no distinction between new and old techniques, only with the desire to create something. So there are no taboos?

Ay-O: No, there are no taboos. We use any method and create whatever we want.

Matsuhashi: How do you want to be remembered in the art world? How do you feel about this? I mean how do you want to be thought of in the future?

Ay-O: I have never thought about it. I have never made a work thinking about what other people would think of it.

Matsuhashi: I think your interest is in creating artwork, so you don’t have that kind of thought?

Ay-O: I’ve never really considered how I want to be remembered. I just focus on creating various things on my own. I don’t concern myself with others’ opinions or whether my work will sell. I’ve never thought about how people might perceive my creations.

Matsuhashi: I think it means that we’re not focused on creating works with the intention of leaving a legacy for future generations. We appreciate what’s around us, but Mr. Ay-O, you simply create.

Ay-O: “I just create”.

Matsuhashi: I would like to hear your philosophy of art. How do you explain and understand the importance of art?

Ay-O: I’ve never thought of art as being particularly great or important.

Matsuhashi: It doesn’t seem like you’re trying to leave a legacy or have a specific belief or philosophy about it.

Ay-O: Every day, you create spontaneously, and more and more works of art come into being.

Matsuhashi: Art is not something you make because someone tells you to, or because you are ordered to. It is not something you make because you want to be popular or to be praised. It’s not driven by any particular thoughts.

Ay-O: I don’t make art because of deep thoughts or intentions. It comes naturally.

Matsuhashi: So you have an internal urge to create. I suppose you could say, Mr. Ay-O, that your artistic philosophy is that you don’t have a specific philosophy.

Matsuhashi: Do you have any last questions or messages you would like to ask people?

Ay-O: I hope people will look at my work and reflect on it.

Matsuhashi: Your work has recently been showcased in several prominent locations,

including the Smithsonian Institution in the U.S. and M+ in Hong Kong. In June 2024, it was also on display at WHITESTONE GALLERY HONG KONG, where it has drawn many visitors. I’m confident that interest in your work will continue to increase. Thank you very much for your time today.

Ay-O: Thank you very much.

©2024 Ay-O