Avery Singer. Free Fall

11 October – 22 December 2023

Hauser & Wirth London

23 Savile Row

London W1S 2ET

With ‘Free Fall’, her first solo exhibition in the UK, American artist Avery Singer reflects upon her personal experience of the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City and explores the wider societal impact of collective trauma and proliferating image culture and media dissemination. Based entirely upon Singer’s childhood memories, the works and architectural intervention in ‘Free Fall’ are a testament to the power of memory—and a memorial to a moment of terror and survival.

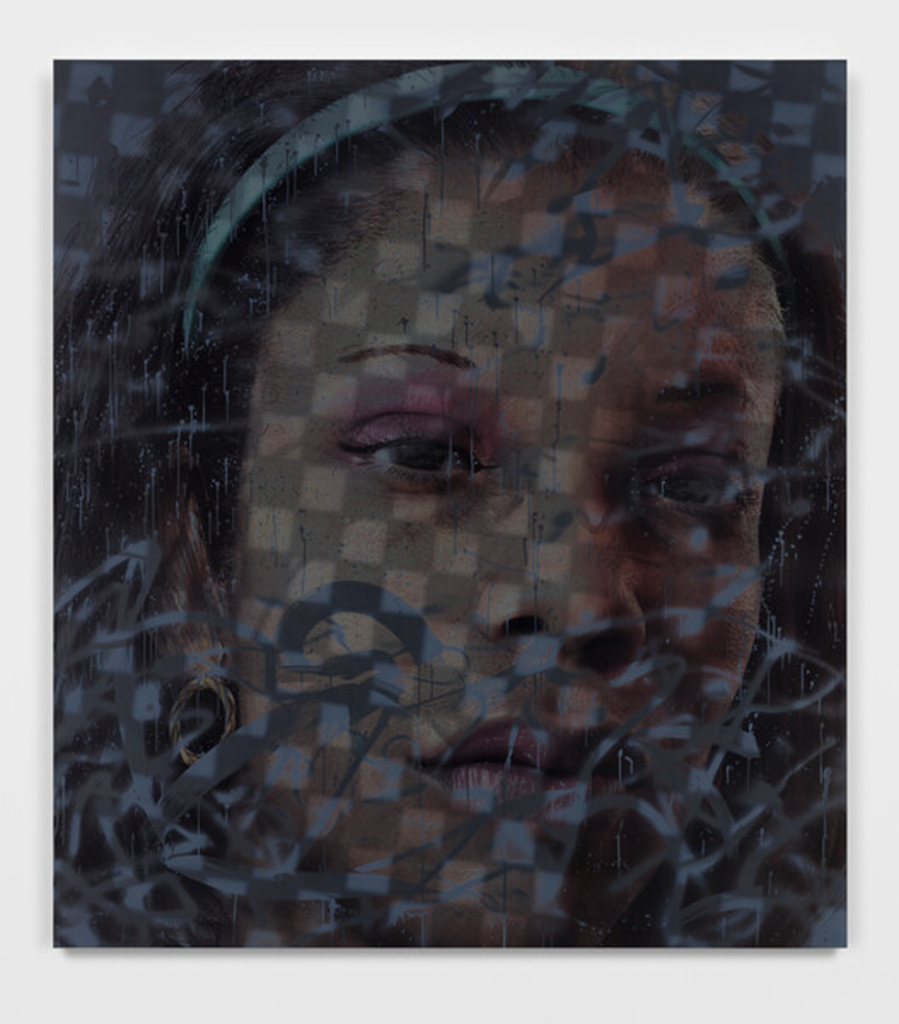

Deepfake Marcy

2023

Acrylic on canvas stretched over aluminum panel

216.5 x 241.9 x 5.3 cm / 85 1/4 x 95 1/4 x 2 1/8 in

Courtesy the artist

© Avery Singer

For the exhibition, Singer has created an environment that replicates her memories of the interior of the World Trade Center offices—spaces she regularly visited in the years prior to 9/11, as her mother worked in both towers of the World Trade Center. Here, Singer combines the atmospheric banalities of office life with the architectural specificity of the towers’ iconic design by Minoru Yamasaki, creating a quietly disorientating installation that is part stage-set, part minimalist sculpture.

Within this environment, the artist displays new paintings that bridge the gap between the anonymous digital world and her own interior universe by merging computer generated worlds created on programs such as Autodesk Maya, the same 3D software used to build the exhibition’s immersive architectural environment based upon Singer’s memories.

Since 2010, Singer has employed the binary language of computer programs and industrial materials to remove the trace of her own hand while engaging the great traditions of painting and the legacy of modernism. The new large-scale paintings on view in ‘Free Fall’ combine digital renderings with manual and digital airbrush techniques, liquid and solid masking, and complex layering processes.

Avery Singer gives her personal account in the following statement:

‘Free Fall is part of an ongoing body of new work that combines changes in my painting technique, to construct images using high-definition digital rendering and poor-quality machine airbrushing. This development also brought with it a shift in subject matter, to explore something autobiographical that took place in my life before I became an artist.

unk-righthand.obj

2023

Acrylic on canvas stretched over aluminum panel

216.5 x 241.9 x 5.3 cm / 85 1/4 x 95 1/4 x 2 1/8 in

Courtesy the artist

© Avery Singer

I turned fourteen on September, 10 2001 and had just enrolled in high school. The following morning, home alone in my parents’ Tribeca apartment, I heard a plane, followed by an explosion that felt like an earthquake. From my front window, I saw the north tower of the World Trade Center in flames. Later, I found myself watching people fall to their death, wondering if they’d chosen to jump. I evacuated

downtown and that night, my family and I slept in the projection booth at MoMA, where my father worked as a projectionist.

When considering this event now as an artist, one thing that strikes me is the change in image culture between 2001 and 2023. Today, we live in a reality in which tragic events can be livestreamed and broadcast on a mass scale. If 9/11 happened today, we might have seen people’s real-time footage, an audio-visual experience of the last moments of their lives, every pixel of their trauma being put online.

Unlike those in the vicinity, most people viewed 9/11 as a cinematic event on television; gruesome images of human body parts scattered across my neighborhood are burnt into my memory. When I thought about how to approach my experience of 9/11 in my mid-thirties, I wondered how I could I filter these fragmented images through the lens of making art: the injured man I saw lying in the doorway of my school, the engine from the second plane which exploded on my street, a severed hand found on my best friend’s windowsill. And I also thought about the images I experienced second-hand in the media—particularly the ‘famous’ faces of 9/11, such as Marcy Borders and Rachel Uchitel.

I allowed myself to be intuitively led by these images and began to make computer models of them, to memorialize my own experience and create a monument for that moment in time. I took Renee Jeanne Falconetti’s acting from The Passion of Joan of Arc as a source of inspiration for the portraits, also evoking the iconic stylization of the 1950s starlet. The portraits, which I have titled deepfakes, are mostly based around photographs I have gathered of the subjects. They aren’t manipulated using AI, but I have added details (such as makeup, jewelry, dust) that cannot be found in any of the original photos. A fictitious character I call “art student” is depicted smoking an opium or crack pipe, an avatar depicting myself from an earlier time in my life. These images are interspersed with paintings of objects, including a severed hand, a cop car, a local bus station, and other fragments of my memories.

I began conceptualizing the layout of the exhibition pre-9/11, and constructed details of the interior architecture of the two towers. My mom had worked in both the north and south towers up until 2000 as a secretary, so I’d spent a lot of time in the buildings. There were these incredibly long, narrow, windowless hallways—I’d walk past suite after suite, each demarcated with a number. I remember the iconic eighteen inch slit windows, designed by Minoru Yamasaki to combat people experiencing vertigo, so distinctly.

Courtesy the artist © Avery Singer

I’ve designed the exhibition space to recreate architectural elements as an installation within the show, so that it feels as if you’ve walked into the lobby of an office, both past and present. The windows, elevator doors, bland carpet, curtains, building materials, and paint finishes, all conjure a corporate environment. I wanted to create something that is part minimalist sculptural installation, part stage-set, a space that forms a narrative backdrop for my paintings. I’ve also designed a bookstore that will house self help books, reminiscent of the Borders below the towers that I visited as a kid, looking at books like ‘Chicken Soup for the Soul’ by Jackhansen Canfield.

In confronting this topic, I wanted to use art as a kind of conceptual mediator, to create an emotional landscape of this history for the audience to enter into and define their own experience.’

As part of Hauser & Wirth’s global learning platform, this exhibition will be complemented by an Education Lab for the first time in the London gallery. In keeping with the concept of memory in Singer’s works, visitors will be encouraged to transform their own personal positive memories into physical form through creative writing and drawing. The solo exhibition ‘Avery Singer: Unity Bachelor’ at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Miami is also on display until 15 October 2023.

©2023 Hauser & Wirth London