From South London train yards to gallery walls, Remi Rough blends graffiti, geometry, and rebellion into an abstract language all his own

In the austere, abstract compositions of Remi Rough, tension simmers beneath the surface — a collision of urban grit and modernist precision. Blocks of colour veer like trains in motion. Lines slice through space with the rhythm of sound systems and spray cans. What might first appear purely formal soon reveals itself as a language born on the steel of South London’s railway tracks.

“It’s like a varnish that runs through the entire body of my work,” Rough says of his graffiti origins in the 1980s. “Graffiti taught me discipline, form, rhythm, and an intuitive understanding of colour and composition.” That education — earned not through critique but on rooftops and in train yards — became his artistic foundation. “There are no abrupt shifts,” he adds. “It’s a continuous, layered progression from the early abstraction of letterforms to the language I speak today.”

Courtesy of the artist

Those early years laid the foundation — the patina — for everything I do now. It’s like a varnish that runs through the entire body of my work.

Remi Rough

Now recognised as a leading voice in abstract art and street culture, Rough’s work still carries the imprint of wildstyle graffiti — the most intricate, codified strain of the genre. “Wildstyle is abstraction, plain and simple,” he says. “It’s about deconstructing and reimagining letterforms — bending, twisting, camouflaging them to the point of illegibility.” He never asked for permission. Entirely self-taught, Rough built his own education outside the academy.

His standards remain exacting, even as his method is guided by instinct. That tension reaches its fullest expression in his public murals. The Megaro Hotel in London, created with LX One, Augustine Kofie and Steve More, remains the city’s largest. “Whether it’s a work on paper or a five-storey wall, the fundamentals are the same — composition, balance, movement, energy,” he says.

Yet some of Rough’s most meaningful works exist far from galleries. The Ghost Village project at Polphail — a derelict site on the Scottish coast — was transformed into a temporary open-air gallery. These interventions — including the clandestine Underbelly Project in New York — reconnect him to the purpose behind his work: to disrupt, reframe, and speak through form beyond commercial constraints.

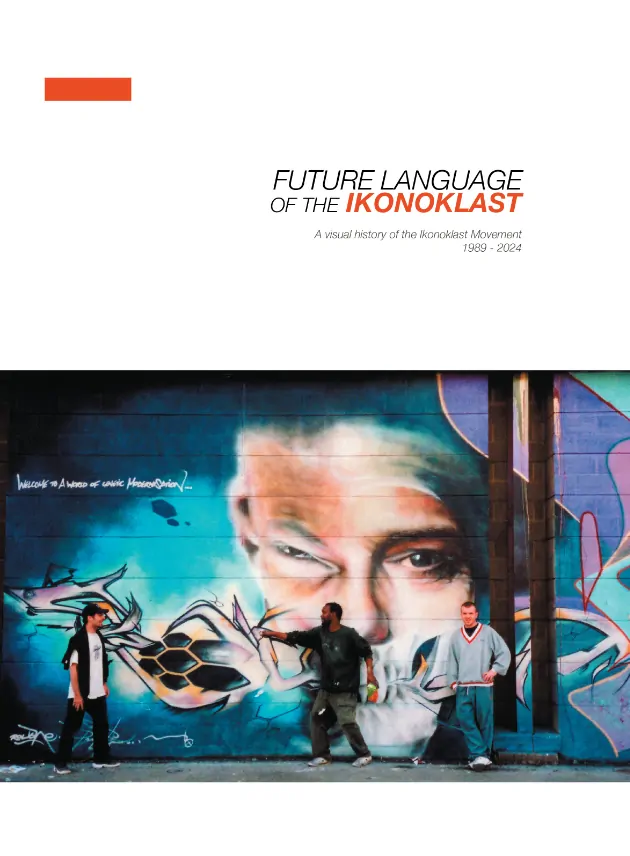

That language finds rhythm in sound as well. A longtime music producer, Rough collaborates with rapper and poet Mike Ladd under the alias TheDeadCanRap. This year, Rough turns to publishing. His new book, Future Language of the Ikonoklast, documents a little-known but pivotal chapter in British graffiti: the late ’80s Ikonoklast Movement, a collective including Juice 126, Jason System and Stormie Mills, that reimagined graffiti through abstraction and rebellion. “Graffiti had its own strict codes,” he says. “What started as defiance had become rigid and self-policing. We wanted to break away from that.”

Their mantra — “rebel against the rebellion” — captured that spirit of transformation. “We weren’t trying to mimic; we were trying to reinterpret,” he says. “We built a shared space of trust, experimentation and mutual respect — a movement with its own values.”

The book, complete with original manifestos, photographs and new texts, is part archive, part reclamation. “The story was being erased — or worse, ignored,” Rough says. “This isn’t just nostalgia. It’s about putting down a historical marker.”

Today, that voice continues to evolve. Whether on concrete, canvas, vinyl or in print, Remi Rough remains committed to pushing visual language forward — shaped by the city, sharpened by resistance, and still speaking in code.

Future Language of the Ikonoklast: A Visual History of the Ikonoklast Movement by Remi Rough is available from Velocity Press from 18 July 2025. Purchase a copy here.

You began your artistic journey painting trains and walls in South London during the 1980s. What aspects of that early graffiti experience still resonate in your work today, both technically and in spirit?

Remi Rough: Those early years laid the foundation — the patina — for everything I do now. It’s like a varnish that runs through the entire body of my work. Graffiti taught me discipline, form, rhythm, and an intuitive understanding of color and composition. While anyone can wake up one day and decide to become an abstract painter, my work shows a clear, traceable evolution spanning over three decades.

There are no abrupt shifts — it’s a continuous, layered progression from the early abstraction of letterforms to the language I speak through my work today. The energy, the chromatic intensity, the physicality of mark-making — all of it comes from those formative years. It’s not just an influence; it’s embedded in the DNA of everything I do.

Abstract graffiti has been described as “visual symphonies”. Where do you see the emotional or narrative power of abstraction compared to your earlier wildstyle graffiti?

Remi Rough: I’m not sure who coined that phrase, but I love it — it captures something essential. The thing is, wildstyle is abstraction, plain and simple. It’s the deconstruction and reimagining of letterforms — bending, twisting, camouflaging them to the point of illegibility. That was always the point: to create something coded, intricate, and inaccessible to the uninitiated.

It was conceptual as much as visual. When people compare abstraction to wildstyle, I think they overlook how radical wildstyle actually was — it’s a form of abstraction born directly from the street, with its own logic and language. What I do now is a continuation of that lineage, just expanded into different visual territories.

You are entirely self-taught. How do you feel that independence has shaped your practice? Has it allowed you to break rules that academically trained artists might have hesitated to challenge?

Remi Rough: For me, there are no rules — and if there are, I’ve never felt bound by them. Being self-taught has been both liberating and, at times, challenging. Some people in the art world dismiss you if you haven’t been through a formal institution, while others value that independence. Personally, I’ve always been deeply invested in learning — I consider myself highly self-educated. I’ve built a significant library covering everything from Baroque painting to minimalism and contemporary installation, and I spend as much time as I can in galleries and museums.

The freedom that comes from being self-taught has allowed me to forge my own path without needing to conform to anyone else’s expectations or academic frameworks. In a landscape that often feels overcrowded and rigid, that freedom is everything to me. Ironically, I think not going to art school may have propelled me further than if I had. I’ve had to define my own standards — and that’s what keeps the work alive. I think it has also given me somewhat of a disdain for the art world in general.

Remi Rough

Courtesy of the artist

You’ve cited modernist movements such as Suprematism and De Stijl, alongside your graffiti roots, as major influences. What is it about these early 20th-century avant-garde movements that speaks so strongly to your aesthetic and conceptual approach?

Remi Rough: Those movements were all about rebellion — about rejecting tradition and creating new visual languages. That resonates with me deeply. Graffiti, or style writing, began as a rebellious act, but over time it developed its own internal codes and hierarchies that sometimes contradict that original spirit of freedom.

What I admire about movements like De Stijl or Suprematism is how uncompromising they were in their pursuit of a new aesthetic logic. They were short-lived in some ways, but their legacies are immense. That’s the kind of impact I strive for — to contribute something distinct to the visual language of our time. The Ikonoklast Movement that I was part of was rooted in similar ideas — of rejecting trends and building something original and self-defined. If my work can add even a small thread to that historical continuum, then I feel I’ve done something meaningful.

Location Peckham

Remi Rough

Courtesy of the artist

There seems to be a constant tension in your work between urban chaos and precise geometry. How consciously do you balance spontaneity and precision when composing a piece?

Remi Rough: That tension is at the core of my studio practice. It’s a constant push and pull — control versus intuition. I’d say about 85% of my work is created spontaneously. I rarely begin with a fixed plan or sketch; instead, I follow impulses and internal cues. Over the years, I’ve developed the ability to sketch in my head — I can see the composition before it exists, and I work from those mental blueprints.

Often, I’ll make sharp U-turns mid-process or even scrap a piece entirely if it’s not working. It’s not a refined or linear process, but I love that. The unpredictability and the willingness to make mistakes often lead to more interesting outcomes. For me, the magic happens in the tension between chaos and control — that’s where the most honest and powerful work emerges.

Much of your work inhabits public space — from expansive murals to the Megaro Hotel façade. How does your approach shift when creating work for the street, as opposed to a gallery setting?

Remi Rough: I actually get asked this a lot, and honestly, there’s not a huge difference in how I approach scale. Whether it’s a small work on paper or a massive wall, the fundamentals remain the same — composition, balance, movement, and energy. If anything, walls are sometimes easier, simply because I always go in with a clear plan. When you’re working on something five stories high, improvising can quickly turn into chaos. Sticking to a design helps maintain control and consistency — it’s about making life a bit easier when the logistics are already so demanding.

Remi Rough

Courtesy of the artist

That said, things shift when it’s a collaborative project. Take the Megaro Hotel mural in London, for example — that was a collaboration between myself, LX One, Augustine Kofie, and Steve More. Each of those artists brings their own technique, rhythm, and way of working, so we had to find a shared visual language that allowed us all to contribute without compromising the integrity of the piece. It was a real negotiation of styles, but in the best way.

That wall has aged beautifully — nearly 14 years on, it’s still the largest mural in London and has become part of the city’s visual fabric. It’s almost like it grew into its environment, which I love.

The Megaro project was also a real journey in terms of labour. Steve More and I carried a lot of the workload once Augustine and LX had to head off, so it was physically and mentally demanding. But the end result was worth it. It’s a piece I’m incredibly proud of.

To be honest, I don’t think any gallery work can quite match the scale, presence, and impact of something like the Megaro mural. There’s a kind of magic to it — it lives out in the world, exposed to the elements, to the city, to time. I remember Banksy once told me he really liked it and said it reminded him of a World War II dazzle ship. I thought that was an incredible compliment. That visual disruption, the sense of movement and concealment — that’s exactly the kind of layered meaning I strive for.

The ‘Ghost Village’ project in Scotland saw you transform an abandoned space into an open-air gallery. What draws you to these large-scale, transformative, site-specific projects?

Remi Rough: The Ghost Village project at Polphail came about through one of my closest friends and collaborators, Timid, who co-founded the Agents of Change collective with me. He was always on the hunt for unusual, forgotten spaces — places with texture, history, and the potential to be reimagined. One day, we came across an article on the BBC about Polphail — this eerie, uninhabited village on the west coast of Scotland that had been sitting derelict for decades. That same week, we planned a recon mission with fellow AOC artist Derm, we went up, shot some photos, and came back buzzing with ideas. Within three months, we were ready to go.

We managed to convince Red Bull to support us with a modest budget — just enough to cover travel, a hire car, and two massive ladders they kindly left on-site. We pulled together a small but powerful crew: Jason System, Stormie Mills, and Juice 126 joined us, and we brought Burial along too — he’s a friend and was keen to make field recordings, which eventually became part of the project’s soundtrack.

This was right after the financial crash — the Lehman Brothers collapse — and the art world was in freefall. That context freed us from the usual commercial pressures. There was no gallery, no brief, no market — just raw creativity in a space that allowed for total freedom. It wasn’t without risk: we encountered open manholes with dead sheep, crumbling architecture, and plenty of hazards. But for three days, it was ours — a temporary museum without walls, where anything felt possible.

I’m drawn to these kinds of projects because they strip art back to its essentials. You’re responding to a site, to its energy and decay, its ghosts and history. There’s a kind of alchemy that happens when you intervene in those spaces — the artwork becomes part of the environment and vice versa. I’ve been lucky to take part in a few of these rare opportunities, like the Underbelly Project in New York, curated by Jordan Seiler and Logan Hicks. That one involved smuggling over 100 artists into an abandoned subway station and turning it into a secret underground gallery before sealing it off forever. It was a fleeting moment, but incredibly powerful.

These projects are few and far between, but they’re where I feel most connected to the roots of why I make art — to disrupt, to transform, and to create something meaningful in the margins. There’s even been quiet talk of doing something similar at a disused airfield with wrecked planes… but that’s still under wraps for now.

Courtesy of the artist

Your experience as a music producer seems to lend a rhythmic quality to your visual compositions. In what ways do sound and visual art influence one another in your creative process?

Remi Rough: The process is actually very similar for me — both are about layering, editing, improvising, and responding in real time. When I make music, it’s very much a cut-and-paste, collage-style approach, not unlike how I construct my paintings. I’m incredibly lucky to collaborate with one of my closest friends, rapper and poet Mike Ladd. He’s a phenomenal artist — his album Welcome to the After Future is listed in 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die, which gives you an idea of the weight of his work.

I’ve always thought of sound in visual terms. Back in the early 2000s, I was designing record sleeves for labels like Ninja Tune and Jazz Fudge, so that link between audio and image has always been integral to how I experience music. With my solo work, and with TheDeadCanRap — the project Mike and I created — I try to ensure the music is coming from the same conceptual and emotional place as my visual art. It’s all part of the same conversation, really. When you’re deeply invested in both fields like I am, the boundaries between them become increasingly blurred. They feed off each other.

Music is also a big part of my painting process. I always have something playing in the studio. Lately, I’ve been diving deep into jazz — Alice Coltrane, Sketches of Spain by Miles Davis, Ron Carter… those textures and moods absolutely seep into the work. My taste in sound is as eclectic and exploratory as my visual influences. At the end of the day, it’s all about energy, emotion, and atmosphere — whether it’s coming through a speaker or onto a canvas.

A Visual History of Ikonoklast Movement

By Remi Rough

Courtesy of the artist

Your new book, Future Language of the Ikonoklast, documents a pivotal moment in British graffiti history. What motivated you to tell this story now?

Remi Rough: It just felt like the right moment. The Ikonoklast Movement has always held a unique place in the story of British graffiti, but it’s a chapter that’s often overlooked or omitted altogether. We staged a small exhibition in October last year, which really helped crystallize the idea for the book — I’d already been working on the concept for a while, but the exhibition fast-tracked everything. I curated it with Part 2, and with help from artists like Stormie Mills, Juice 126, and Jason System, we began gathering images, archives, and stories that became the backbone of the book.

I’ve known Simon Armstrong, Head of Books at Tate, for years — he’s an old friend and someone who already had a strong sense of the cultural weight of the movement. Having him write the foreword just made sense. I was also working on an exhibition proposal with Lois Oliver, an accomplished art historian who’s curated major shows for the Royal Academy and Dulwich Picture Gallery. Initially, she was hesitant to contribute — she felt it might be outside her comfort zone — but she absolutely threw herself into it. She conducted interviews, did meticulous research, and wrote a phenomenal text that gives the project real academic and historical depth. I’m incredibly grateful she agreed to be involved.

But if I’m honest, the real credit for pushing this into existence goes to Kid Acne. He’d been on at me for years to do a book or a documentary about the Ikonoklast Movement. He’s always cited it as a major influence on his own work, and he understood its cultural significance better than most. Fortunately, between myself, Juice, and Jason, we’d managed to keep hold of everything from those days — negatives, photographs, flyers, letters, even the original manifesto that Juice sent out in 1989. We were sitting on an archive that hadn’t been shared in any real way.

What also drove me was a sense of responsibility. The Ikonoklast story had been excluded from some major UK graffiti and street art exhibitions, and I felt it was important to correct that — to make sure the movement was properly documented and preserved for future generations. This book isn’t just about nostalgia; it’s about putting down a historical marker and reclaiming space in the narrative of British art history. The time was right — and the story deserved to be told.

Courtesy of the artist

The Ikonoklast Movement’s mantra was “rebel against the rebellion”. Can you elaborate on what that phrase meant to you and your fellow artists at the time?

Remi Rough: “Rebel against the rebellion” was about reclaiming artistic freedom — pushing beyond the limitations that even so-called rebellious art forms can impose. By the late ’80s, graffiti and style writing had developed their own strict codes: how letters should look, what styles were valid, what rules to follow. Ironically, what started as an act of creative defiance had, in many ways, become rigid and self-policing. We wanted to break away from that.

Artists like Futura 2000 were already challenging those conventions. His abstract wholecar from 1982 — which I didn’t see in full until years later — had no name, no characters, just pure form, colour, and movement. It was radical in its restraint. That piece, and others by RammellZee and A-One, showed us that there was a path beyond traditional graffiti — one rooted in personal expression rather than adherence to inherited rules. They were rebelling against the rebellion, and that gave us permission to do the same.

But we were also operating in a different context — we were British, outside the New York scene, and that distance allowed us to reimagine what graffiti could be. We weren’t trying to mimic; we were trying to reinterpret. That meant forming something new — not just stylistically, but socially and structurally. When I say we “built a community,” I don’t just mean we had a group of artists hanging out. I mean we created a shared space of trust, experimentation, and mutual respect — a collective with its own values and vision. That spirit of exchange and openness is what transformed our circle into a movement.

The Ikonoklast Movement wasn’t about rejecting graffiti — it was about evolving it. About creating space for the kind of innovation and individuality that had once defined the culture. “Rebel against the rebellion” reminded us to never settle, never conform, even within the spaces we helped shape.

Looking back, how do you feel the Ikonoklast Movement’s desire to move beyond the so-called ‘rules’ of New York graffiti influenced not only your own trajectory, but also the wider international graffiti scene?

Remi Rough: That first decade taught me everything — how to paint, how to experiment, how to collaborate. Those skills became second nature, forming the foundation of my entire practice. But what was equally important was the mindset we developed: the belief that graffiti didn’t have to follow inherited rules, that we were allowed — even obligated — to push it somewhere new.By the early 2000s, when I came back to painting after a break, I made a conscious decision to strip everything back.

I focused almost exclusively on letterforms — painting them in black on flat colour backgrounds — really reducing things to their essence. From there, I began to deconstruct the letters further and further, until I arrived at the abstract language I use today. That evolution wouldn’t have happened without the Ikonoklast Movement. It gave me the permission to question everything, to take things apart and rebuild them in my own way.And I don’t think it’s arrogant to say that we helped break the mould — that’s exactly what we were trying to do. We wanted to liberate ourselves, and in doing so, we opened the door for other artists to find their own voices too.

You wouldn’t have the hyperrealist muralism you see today without the influence of people like System and Part 2. They were painting mind-blowingly detailed pieces decades ago — using terrible automotive paints, stock caps, even handmade stencil caps. No specialised tools, no curated colour palettes, just raw talent and ingenuity.Today, there’s an entire industry built around wall painting — purpose-made spray paints, endless cap varieties, corporate sponsorships.

Back then, we had none of that. We made do with what we had, and I think that gave our work a kind of edge and honesty that’s hard to replicate.Artists like Juice, who I often call the British Futura, were breaking new ground in abstraction and conceptual style work before most people even knew what that was. Stormie Mills is now a major figure in Australia. Chu runs an incredible design agency and creates large-scale installations. Part 2 continues to push abstraction into bold, conceptual territory. System remains one of the most technically gifted illustrative graffiti artists the UK has ever produced. And I’m still making my work, still evolving.So yes — looking back, I’d say that’s mission accomplished. At least… so far.

©2025 Remi Rough