Terror, disruptions of liberty, incarceration, and War echo throughout the work of British artist Edmund Clark, a powerful practice, potent in its approach yet aesthetically gripping. Clark delves into the complex interplay of state power, personal experiences, and the mechanics of control in times of conflict, effectively linking history, politics, and representation.

Credit © Oliver Abraham

I am often having to develop ways of visualising or representing subjects that are unseen, hard to see, cannot be shown, or hidden or obfuscated in some way.

Edmund Clark

That delivers a rousing narrative scrutinising the intricate facets of human experiences under duress. Clark’s photography makes your soul shiver as you are greeted head-on with the reality of secure detention, humanities rendition of the Zoo with no visitors; this is seen in Clark’s ‘Guantanamo: If the Light Goes Out.’

This series vividly captures the realities of incarceration and the disruption of liberty, offering a haunting reflection on the human cost of conflict, its dystopian, raw and cold. In works such as Camp 6, part of the series abstractly captures the essence of modern-day slave shackles. The image shows several cushioned ankle bracelets scattered across the grey, unforgiving concrete floor of the infamous security facility linked together by cold, unyielding metal chains.

This piece provides a stark contrast and is thought-provoking: the softness of the cushions against the brutal reality of confinement evokes a complex mix of emotions. This series also signifies Clark’s dedication to researching his themes. Gaining firsthand access to Guantanamo allowed him to dive into the facility’s complexities from a unique perspective: inside it, feeling its ambience, speaking with ex-Guantanamo and former CIA black site detainees, expressing dynamic stories that go beyond typical narratives.

In ‘Negative Publicity: Artefacts of Extraordinary Rendition,’ Clark and investigator Crofton Black expose a dark narrative of covert operations; this series reveals images of ephemeral leftovers from interrogation scenes and secret government locations, echoing the ‘war on terror’ era initiated by President George W. Bush, it reveals the chilling reality of individuals disappearing into the abyss of undercover networks of secret prisons managed by the CIA, where human rights and laws are suspended in a void. This illustrates the terrifying control and exercises of political power wielded outside the eye of legal scrutiny.

Clark’s work has garnered critical acclaim for its investigative approach, bridging complex themes within his regime of artistic expression, which often involves extensive research and collaboration with individuals impacted by the issues he explores. Throughout his work, Clark encourages us to consider the severe implications of political and social actions and their effects on individual lives and human rights. We managed to catch up with Clark to learn more about his practice, inspiration, and more shortly after his work “Control Order House” was acquired by the V&A from Flowers Gallery and will be on show at V&A Photography Centre in June.

Hi Edmund, How are you doing? Could you share with us how you got started with photography, your journey into the arts, and what led you to pursue a career in this field?

Edmund Clark: I grew up surrounded by images as my father always painted and collected drawings and sketches by other artists. I started late as a photographer, though. I did a history degree and worked for five years before giving up my job and travelling. By chance, I then met a tutor from what is now the London College of Communication who told me about a one-year post-graduate diploma in photojournalism.

So, I started as a photographer working for magazines and design agencies but always developing my own projects for publication. These got longer and more complex in terms of subject matter and form until they took over. My work developed into books, installations and exhibitions – and I was fortunate to have opportunities to show work with galleries and museums.

Throughout your practice, you explore themes of power, conflict, and control, focusing on individuals’ experiences in complex global scenarios like terrorism, war, and state control. Let’s delve more into your practice, how you approach these topics, and why they are of significant interest to you?

Edmund Clark: In terms of subjects, I was moved to pursue my interests in systems of power and control because of their importance and because of what was happening in front of me. Initially, through work about incarceration and criminal justice,then in response to unseen processes and experiences of detention, control and interrogation in conflict and counter-terrorism measures.

These are significant because they define what sort of societies we live in. They expose the political underbelly of our systems – how power is used and why, and the individuals over which this power is exercised, and the messages or justifications for this.

Building on that question, could you walk us through your creative process? How do you conceptualise and then execute a project? What does your research process involve when preparing for a new project?

Edmund Clark: I approach each project differently. I am led by what I know or can find out about a subject, how it is represented in the media and by the government or system of power involved, what I think an ‘audience’ may know or recognise about a subject, and what access I can get to key individuals and locations.

I look at the media a lot, read relevant material, and talk to experts (often lawyers) and protagonists caught up in these events. I am often having to develop ways of visualising or representing subjects that are unseen, hard to see, cannot be shown, or hidden or obfuscated in some way. That is an interesting challenge. In terms of conceptual form, I try to visualise how a project could work in different ways and on different dissemination platforms.

Can you discuss the role of combining photography with documents and other media in your work? How does this enhance the narrative?

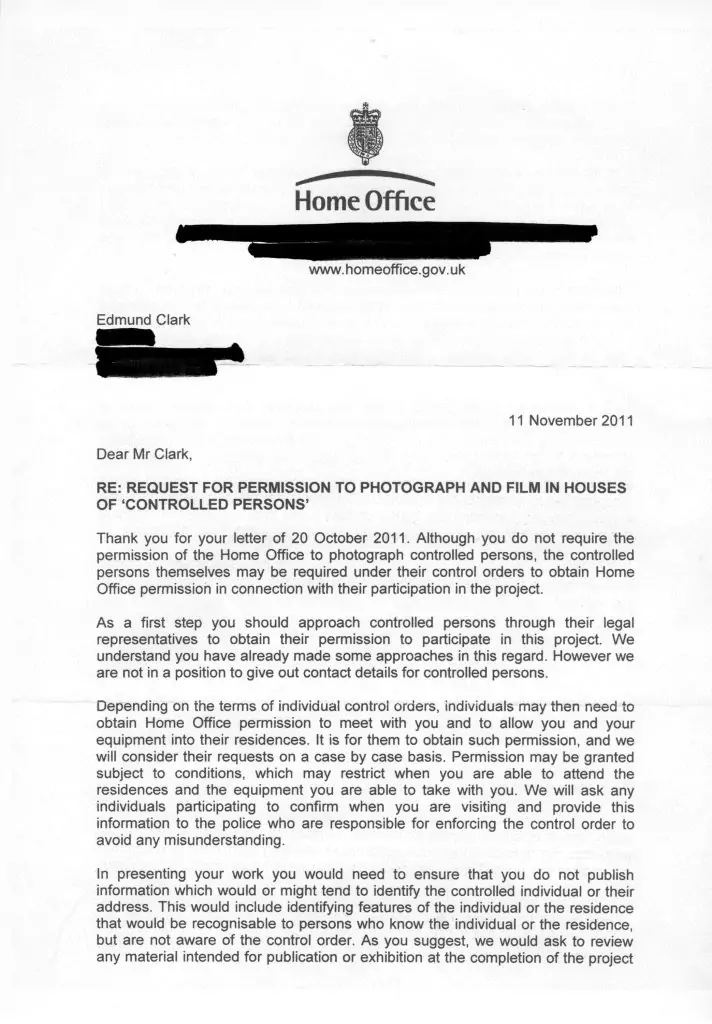

Edmund Clark: Documents of administration and bureaucracy are interesting as evidence in terms of their content as words or diagrams and as visual things that communicate through the forms they take in the processes of their production. Pieces of paper are often the interface between individuals and the authority or system that is exercising control over them. These pieces of papershow traces of this through how they are produced and the language they contain. They also exist as traces of networks of activity. Banal but politically charged. Particularly if they are redacted.

The images I make (or use) to go in conjunction with documents, in finished outputs, have to work formally in response to these pieces of paper, and what they show or don’t show. Sometimes, there is a formal need for visual variety; sometimes, there is a conceptual resonance between what documents and images do or don’t show. Lens-based media are predicated by looking and showing. Using the lens to define what you can’t see or show, is, therefore, more interesting – and important.

Can we discuss one of your key works, “Guantanamo: If the Light Goes Out?” What were the challenges in portraying such a complex and politically charged subject?

Edmund Clark: Visualising the complexity behind a subject that is represented through such simplistic, stereotypical and charged narratives. Responding formally to the way my understanding of the subject evolved over time, and the material that related to this. Incorporating different types of visual material to develop a different and more complex representation of the subject. Getting access to Guantanamo and to the individuals who have been held there.

Building on that question, how do you navigate the ethical implications of your work, especially when dealing with sensitive subjects like terrorism and detention?

Edmund Clark: My work is ultimately about systems and processes of power and control, but it has involved working with people who have been profoundly impacted by experiences of detention, interrogation and torture. These relationships are an essential part of my research and process. There are ethical implications concerning these relationships and how these individuals’ experiences are represented.

My work looks at the ethical and legal impact of the measures taken in response to the threat of terrorism, so the impact of terror, and the charged representations of this in the media, have implications for how to present and contextualise my projects.

Can we discuss the role of an artist in political and social discourse? What, in your opinion, is that role?

Edmund Clark: I think the role of an artist is to question and to find strategies for exploring and recording what is going on behind the official messages and processes. It is very unusual for artistic, documentary or editorial work will directly impact government policy, but it can and does effect discourse around and representation of political and social subjects. I think the role of the artist is to engage in this through their work.

Chromogenic print

40 x 50 cm

15 3/4 x 19 3/4 in

Edition of 10 plus 1 AP (#0/10) (c) Edmund Clark, courtesy of Flowers Gallery

How do you envision your work evolving in response to changes in the global political landscape? Are there any new themes or issues you plan to explore?

Edmund Clark: I am continuing to look at the ongoing legal and ethical implications of twenty-first-century conflict. In terms of new themes, I am developing a body of work with the investigative researcher Crofton Black. This is an exploration of knowledge and meaning in relation to the overwhelming edifice of power that is the budget and image of the U.S. Department of Defense. It uses an analysis of scale to define the granular detail of the military-industrial complex.

Chromogenic print

66.5 x 85 cm

26 1/8 x 33 1/2 in

Edition of 8 plus 1 AP (EC 1/1) Edition of 10 plus 1 AP (#0/10)

(c) Edmund Clark, courtesy of Flowers Gallery

From billions for global destruction to quarters for cookies, this new work shows the global breadth and depth of influence of the American military dollar and the U.S. military’s self-representation and soft power as it reflects on its activities at home and around the world in the 21st century. I am also interested in working collaboratively on shared readings of archives and images with artists, writers and academics from, and interested in, countries from the region defined as the Middle East and North Africa. To share contemporary readings of archives to develop understanding of the political histories of this area, and the events taking place there today and in this century.

Looking back at your career, is there anything you would have done differently in your artistic journey?

Edmund Clark: I could say I would like to have started earlier, but I do think that life experience is important in informing the singularity of each creative vision. Having said that, I could have found the time to read more, and learnt a musical instrument for my sanity.

How do you view the role of art in today’s society, particularly in an era of digital media and rapid information dissemination?

Edmund Clark: I think the artist in today’s society has to think about their relationship to the systems of control and ownership behind digital media and platforms disseminating information. In turn, do they want to critically reflect on the complexity of the world they inhabit or provide entertainment and decoration for rich people? Perhaps the most successful artists do both.

Lastly, could you share your philosophy of art? How do you define and interpret the essence and significance of art in your life and work?

Edmund Clark: It’s what gets me out of bed in the morning.

©2024 Edmund Clark