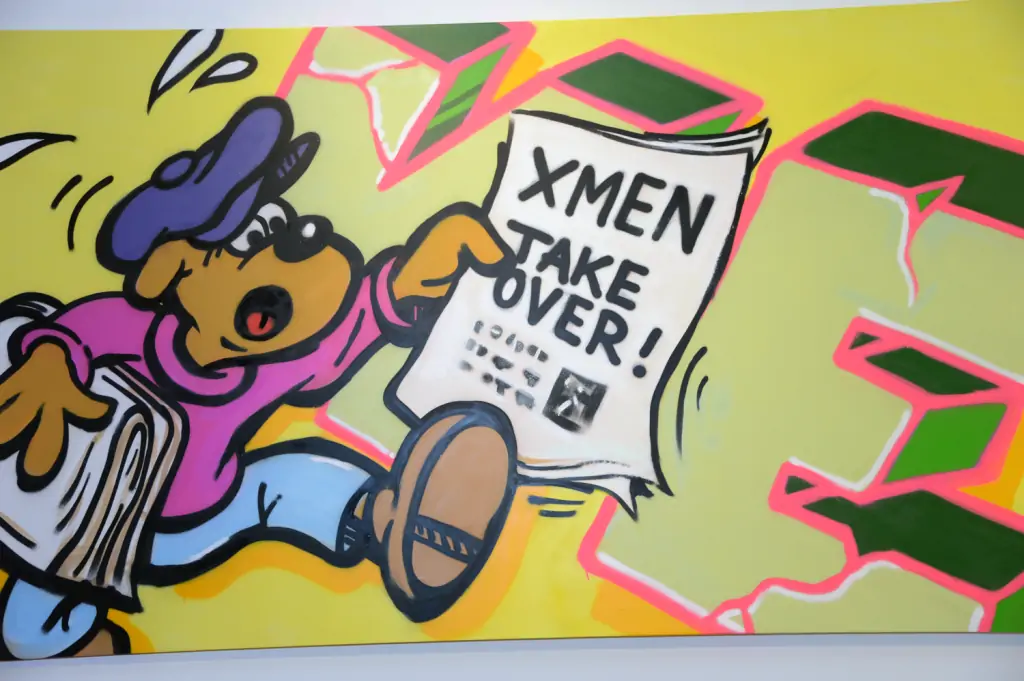

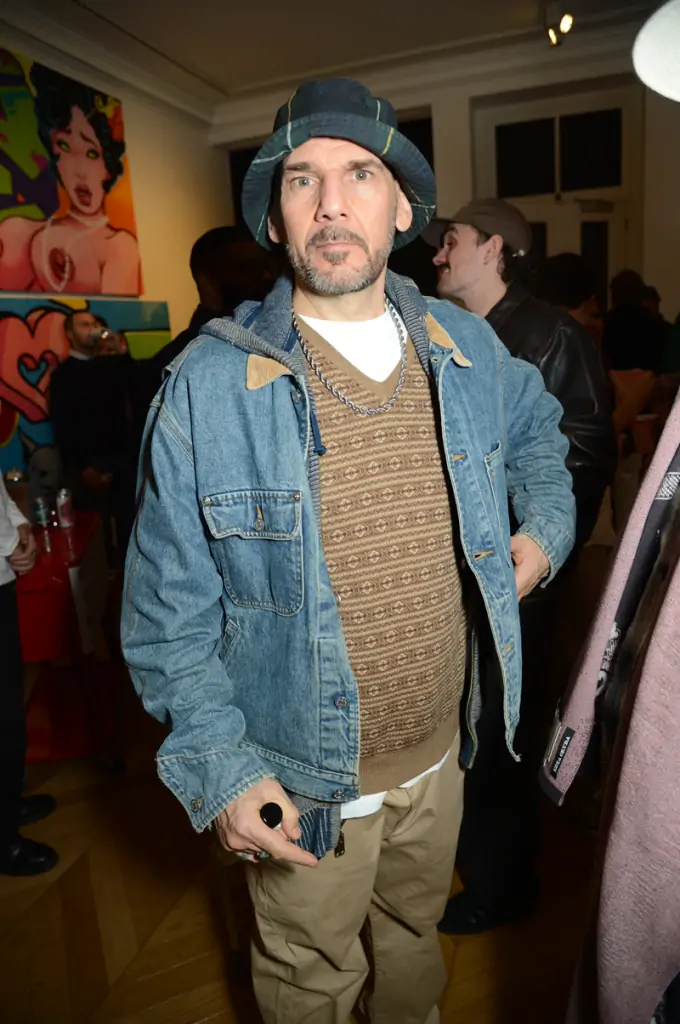

In today’s landscape of Graffiti, or as some say, Street Art, there are only a few original Kings left from the golden era of subway canvases and aerosol artistry; genuine monarchs from this realm are a rare breed. And I was lucky enough to sit down with one of them, the legendary graffiti writer KEO from New York City’s X-MEN crew, to learn more about his craft, history and more.

Hailing from Brooklyn, the cradle of his creativity, KEO became obsessed with Graffiti at a very young age, viewing the writers as elusive superheroes as he saw their tag appear almost out of nowhere; this sparked his intrigue. Yet, it wasn’t until he blessed his first subway train that KEO was anointed as a writer.

It’s my duty to continue to show them the authentic. This is not the sparkly Hollywood version. This is the real

KEO-XMEN

KEO wrote under a few names, KEO-XMEN being one of them, and also as Lord Scotch or Scotch 79, leading him to become a mythologized underground figure. In parallel to his writing, KEO is celebrated for his creative direction, illustration, and influence on numerous Hip-Hop groups in the early to mid-80s. KEO is tied to the fabric of New York City’s Graffiti World and has deep roots in the inner circles of old-school Rap. There’s even word of KEO being the first White Rapper.

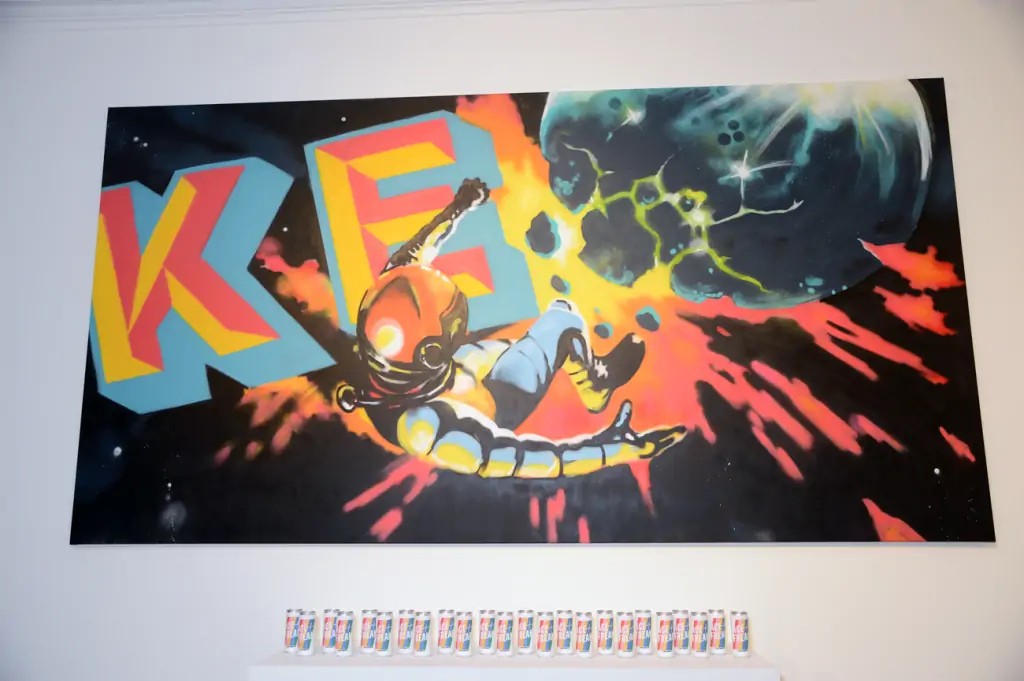

KEO’s work is deeply rooted in traditional subway graffiti, blending elements of pop culture, comics, and classic animation. His commitment to preserving the historical essence of subway writing is evident, with a focus on styles dominant in the early stages of the movement during the 1970s and 1980s. This approach reflects his profound respect for the origins and evolution of subway writing.

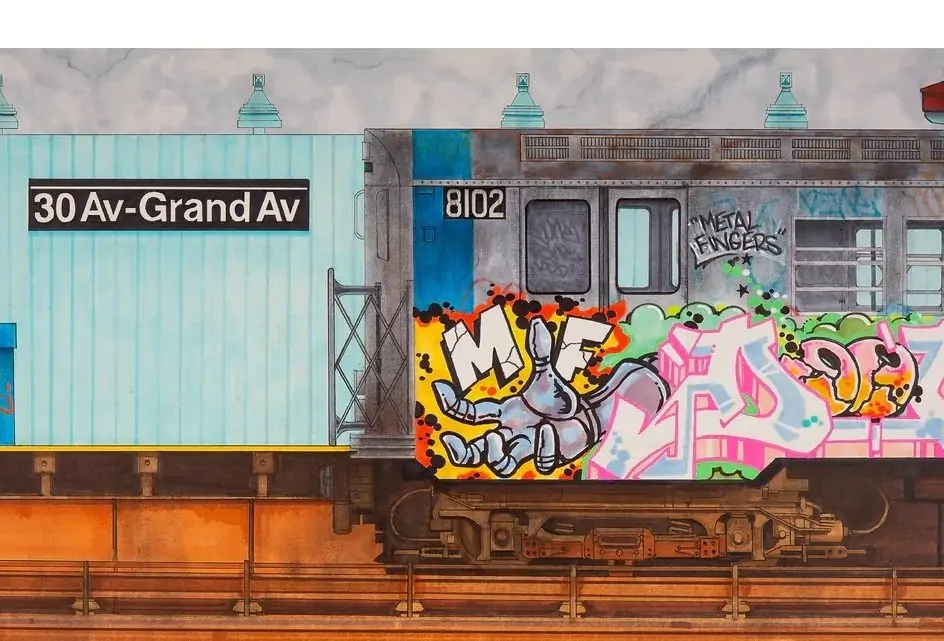

Unlike contemporary graffiti artists who often utilize a wide range of modern tools and technologies, KEO strictly uses only the original tools available in subway writing’s nascent stages, such as spray paints and markers. Inspired by the ones who came before him, he embraced the tradition to hone his aesthetic. In his roles as an art director and creative illustrator, he is celebrated for his work with “your rapper’s favourite rapper“, all-caps MF DOOM, creating the legendary artwork for DOOM’s Operation Doomsday and his first and second masks. KEO’s career is a story of resilience, homage, and respect. KEO shares his path into art, writing, music, and more in this in-depth conversation.

Hi Keo, please introduce yourself to those who may not know you. Could you share your journey of how you first became involved in graffiti and what drew you to this particular art form?

KEO-XMEN: My name is KEO, XMen Crew from Brooklyn, and I became obsessed with graffiti as a very young child. I was always artistic; some kids draw on the walls with crayons; I just never stopped. It seemed really mysterious and intriguing to me how this artwork was done, who had done it, and when they did it. It just seemed to appear out of nowhere.

I noticed pretty young that the other kids had a sense of awe and respect for these guys. They were almost like superheroes in my mind because they had a secret identity like Zorro. So I knew pretty young that’s what I wanted to do, and I was willing to go to any length to figure it out. Some kids are obsessed with a sport or learning a musical instrument. But I feel really fortunate that I found my passion early, and it’s been something that has carried through.

© KEO-XMEN

Reflecting on your early days, especially your first show at FUN Gallery alongside prominent artists like Basquiat and Haring, how did these experiences and interactions shape your artistic vision?

KEO-XMEN: Honestly, there were so many graffiti artists that I really admired. Though Basquiat, Haring, Kenny Scharf, Richard Hambleton, and some of what they called the East Village School at that time, street artists were showing with us, that wasn’t the stuff I was drawn to. I was really drawn to the mechanical lettering, wild style, guys like Dondi, Tack FBA. They had the pieces at the Fun Gallery that fascinated me and that I wanted to emulate.

I respected what Basquiat was doing, but that wasn’t my particular style. There are tons of artists working in the style of Basquiat now. There are many artists working in the style of Keith Haring now; cartoony stuff. I’m trying to keep alive a tradition of lettering that came up in New York City.

© KEO-XMEN & Woodbury House

There were other movements in other places. I wasn’t aware of them. What I’m really focused on is what developed between like 1972 and 1982. This style was evolving so rapidly, and it was incredible. I was watching before my eyes innovation, because it’s a very competitive art form. Right?

If one guy did an arrow on his piece, the next guy, the next night, was like, “I’m doing three arrows.” “Oh, he did polka dots? I’m doing stars.” That quickly was the impetus for rapid development and innovation to where this thing became super technical, almost like architecture, schematic drawings, or blueprints, really, really advanced geometry.

Sometimes, with fine art, I don’t see that; the math involved in it, you know. The technical side of it is what really intrigued me because it’s not easy, and I still haven’t mastered it. That’s why I’m still working in this style because there are things that still elude me. You know, maybe once I get it perfect, I’ll be bored with it, and I’ll be ready to do something else.

Building on that question, your style fuses traditional subway graffiti with elements of pop culture, comics, and classic animation characters. Can we delve into your creative process and inspiration?

KEO-XMEN: So, in the ’70s in New York, I was born in 1967, so by the time I got to school, the city was bankrupt, right? There’s no money for public school arts programs. When the budget gets tight, arts are the first thing to get cut. So we had no music program, we had no art supplies, and we had to look elsewhere for our inspiration to study. We were looking at sign painting, comic books, and album covers. You have to understand we didn’t have access. Today, you can Google image search anything.

But to get a comic in your hand and be like, OK, this is how they put the shadow on one side and the highlight on the other; this was really instructional manuals for us. If you got hold of like a Parliament-Funkadelic album or Earth Wind and Fire, you know, or even a box of laundry detergent, or a cereal box. Captain Crunch had a cartoon character; these are the things we absorbed, sampled, and remixed into our work.

© KEO-XMEN & Woodbury House

There were certain very rare comics that were super hard to find and desirable: underground comics with adult themes. We would go into Manhattan, travelling as young kids to go, try to shoplift these things. It was work; you had to hunt. I learned the proper way to do a three-dimensional letter from Superman, and then later, the X-Men and you still see that in my work. Had I learned from the Dutch masters of classical art and oil painters, my work would look very different today. I’m a product of a specific time and environment.

Today, there are so many amazing tools and digital aids to create things, such as AI and CGI. It’s very easy and accessible, so how do I keep that same sense of wonder and excitement that I had? When I was a kid, making a record was a very rare thing; you had to have a studio, engineers, and money—people behind you and backing you. Now, someone can pick up their iPhone and record an entire album, press a button and send it out to the whole world.

Making a movie. If you were in a film, that was incredible. Somebody from Hollywood had to come find you and whisk you away in a limousine. That was like a one-in-a-million thing. Now, I could make a movie right here, a feature-length film from this phone.

Things are easier, doesn’t necessarily make them better. In fact, they lose some of the magic. It becomes commonplace. It’s no longer miraculous. The sense of wonder that I experienced as a little kid to see an entire train car, eight feet tall, 80 feet wide, painted with psychedelic colours and cartoon characters; how to instil that same sense of wonder in the next little kid when they’ve got everything at their fingertips, How do you keep the magic?

Again, I’m going to reference music because there are drum machines that can create perfect patterns, mathematically infallible. The drummer never gets tired. He never skips a beat. But it doesn’t have the same warmth. So, people still go back and sample the funky drummer from James Brown. To loop something human with all its imperfections is what makes it so warm and alive. I could get these perfect. I could tape off every line, I could stencil and airbrush, and it’d be boring as hell.

So I try to do them quickly, and I use only the materials that we had access to back then. It’s just straight spray paint, and I need to work this large because you can’t get fine-line details. For that, I would have to go to an airbrush for some of that. There’s new technical caps and paints that have low pressure that allow you to do things you couldn’t do before, but it doesn’t have the same feel to me.

So, in a lot of ways, I’m anachronistic. I’m like, you know, there are people in Pennsylvania that drive horses and buggies as part of their religion. They eschew anything mechanical or modern. So I’m kind of like one of those dudes, what do you call it, a shaker. I hope that people can see it. Because that’s the thing is that the guys that inspired me, they had a whole lot of soul and a whole lot of funk, and it was never perfect, it was rendered quickly. There’s something about when you move a certain way, naturally loose and flowing quickly, that something comes out that you can’t force or, you know.I looked at a lot of guys and how they did their signature right, and it looked perfect to me, and I would try to emulate it.

And of course…I had to find my own flow, because your body and my body are not the same. So I have a rotator cuff injury that when I do, I form a perfect circle, when I get about here, it goes click. If you notice, every one of my O’s will have a crack at a certain place, and that becomes part of my signature style. No one else’s body is going to do exactly what mine does. So that’s something that’s in your physical makeup, in your DNA, maybe even in your spirit.

© KEO-XMEN & Woodbury House

So if I tried to be Haring or Basquiat, I’ve tried hard to be Dondi, right, I’ve tried to copy his stuff, it doesn’t come out exactly like his. What I thought was wrong as a kid is exactly what’s right with it, because that’s my style. So again, music analogy. If you’re playing a jazz standard that a million other people have recorded, how do you put your own spin on it? I’m working with 26 letters of the alphabet, there’s only so many combinations and permutations in which to arrange them. There’s only so many ways you can bend that letter before it no longer reads as a letter.

So how to put my own little spin on it, and it’s small subtle. I’m not reinventing the wheel. I’m not a maverick or an innovator. This thing evolves by little tiny degrees. Because most of what was going to be innovative about graffiti was all created by 1977, when I’m starting to get into it, there wasn’t a whole lot left to add. This stuff was perfect, man.

Could you walk us through your creative process, from conceptualizing to executing a piece, and how you select locations and the environment’s impact on your work?

KEO-XMEN: Very important because graffiti is site-specific. When it’s on a train car illegally and it pulls into the station, it has incredible power, that if you put it on a canvas in a gallery, it loses some of that impact. Right? It’s no longer illegal. It’s like a tiger. If you bump into a tiger in the wild, that’s an awesome and scary thing. You see the same tiger in a cage in the zoo, and he’s all fat and lonely, depressed, and you know he can’t get at you. So, that element of fear and danger is gone.

Is he still a tiger? How do we define a tiger? Right? A tiger has the potential to smack your face off. So if you take that away, if you take the illegality of this painting away, is there still something of value there? That’s what I’m trying to translate that same power and excitement to canvas. And that’s my challenge, man. I think every graffiti artist’.

Even the hip-hop music that I loved when I was a kid wasn’t recorded in a studio. Early hip-hop, it happened in the park or in a rec centre, in the projects, and it was live, you could hear the crowd in the background, and it was call and response. The quality of the recording cassettes was very low-fi, but it had an excitement. That, often, when those groups like the Cold Crush went into the studio to try to replicate that, it didn’t have the same power, didn’t have the same impact.

© KEO-XMEN & Woodbury House

So I felt that about a lot of graffiti artists that I love. They were incredible on the trains, and then they got the opportunity to have a gallery show, and they didn’t know what to do. Like somehow, and I want to scream at them, like, just do what you f**king do. Do you. Don’t try to change it up for what you think belongs in a gallery. These people came to see you, man. And I have to scream that at myself. I can’t tell anyone else, but I can learn that lesson for myself because I could be a mediocre knock-off pop artist, or I could be a really first-class graffiti writer.

So why would I want to switch up and try to do what’s already been done far better than I’ll ever do it when I’ve spent my entire life mastering this to change lanes now? You know, it’s like Michael Jordan. He decided he wanted to go play baseball. He’s a great athlete, but there are better baseball players, like they already got that covered.

Do what you do best. So, I’m trying to stay within my lane. Maybe, like I said, maybe one day I’ll have mastered this, and I’ll be ready to move on to the next thing. But I haven’t even figured out all the secrets of this yet. I haven’t solved all the mysteries for myself.

© KEO-XMEN & Woodbury House

You’ve worked with legendary Hip-Hop artists and labels, such as Kool Keith, Inspectah Deck of the Wu-Tang Clan, and EPMD. How do you approach the integration of your graffiti style with their musical identity?

KEO-XMEN: You know, a lot of the cats that you mentioned came from the same time and place that I did. I used to try to rhyme; I used to Electric boogie, pop, and lock. They were graffiti writers, too. Back then, you were like a Renaissance man. You didn’t just do one thing. If I said, well, I’m a rapper, OK, that’s all you do? Because we were ready to battle in many different forms.

A lot of these cats already had a vision of what they wanted. So, I’m probably most famous for my collaborations with MF DOOM. Rest in peace. That was like a brother to me, he knew exactly what his visuals looked like. In fact, he could have done all the artwork himself, but he was smart enough to know, I’m going to focus on this music and find someone I trust that gets it, understands the vision.

I was fortunate enough to be that guy for him. But I was basically just the hands because he was the vision; he was the brains. You understand? He knew exactly what he wanted. Other artists, it’s not that clear; sometimes, with a major label, you may never meet the artist. So you’re dealing with an art director and 30 other people between you and that guy. I try to listen to the album, I’ll just have it on repeat while I’m creating the visual. Because if it doesn’t sync, you know, it doesn’t fit, it doesn’t belong.

We have a wonderful marketing team and PR behind this show, and they’ve been putting out video clips to promote it with my work. But the music they chose wasn’t particularly my vibe, and I had to say, “Hey, this is cool, but it’s not me. So how about this?” Boom, boom, boom.

Music is very important to the visual, and the visual is important to the music. I’ve been successful at creating logos, and album covers for artists whom you know….if I didn’t really like your music, I probably wouldn’t do a great job designing your logo. So, I’ve been really fortunate that I’ve worked with artists that I enjoy. I want to listen to their shit. I get it. I’m excited about it. I got it – I can see it already. They inspire, so it’s not difficult. Now, if you told me to work with an artist that I thought was trash, that’d be a hard job to make it look good because I’m going against my instinct.

That vibe, that alignment is very important, and music has always been super integral to my process. I went to a high school in New York. It’s a public school, but it was specialized. So you had to take a test to get in. It was called Music and Art. It was two schools within one. You had music majors who might be vocal or instrument, and then you had the fine arts majors. We went to math and science classes together and then went to our majors separately.

I was real fortunate at the time when I went to music and art, I was there with some of the greatest. I was with Slick Rick, Dane Dane, and these cats every day: MC Battles in the lunchroom and the Fresh 3 MCs.

But not just hip hop, punk rock, great vocalists, R&B, Gospel. You know, the woman who had the lead in the Broadway play “Mama, I Want to Sing” was in my class. Bernard Wright, who made his first album in high school, went to my school, a couple of years older than me. He was graduating as I was coming in. So all these jazz musicians. The funny thing is they were writing graffiti, and I was trying to be an MC. I could never carry a note. I didn’t really want to rhyme. I wanted to be able to sing like Marvin Gaye or Teddy Pendergrass because the ladies like that.

I was real fortunate at the time when I went to music and art, I was there with some of the greatest. I was with Slick Rick, Dane Dane, and these cats every day: MC Battles in the lunchroom and the Fresh 3 MCs.

© KEO-XMEN & Woodbury House

But if you can’t carry a tune, MCing is the next best thing. You don’t have to actually hit a note or stay in a key. You can deliver it in your own natural speaking voice. See, when you do visual art, often, the audience is not there watching you in progress. When you’re a performer, when you get on stage, right, when Teddy Pendergrass sang to the audience, he could feel the reaction coming back at him. They were throwing panties on the stage.

Now, I create something, and I hang it up. Somebody might see it later and have a reaction. Maybe they throw their panties at it, but I’m not there for that. So it’s not that back and forth. The feeding, that’s why an event like we’re going to have here on Wednesday night, is so amazing to me because I get to see people’s reactions.

Once in a while, if you make somebody feel something, that’s amazing power. Like a D.J., man, they can control a crowd. I went to clubs where there were violent killers in the club, and it could have been a problem. If you had to bring the music down, you couldn’t play M.O.P. and then say, “OK. Lights on, everybody go home.” You had to bring the vibes down slowly. The last song had to be like Frankie Beverly and Maze “Before I Let Go“ or “Computer Love“. You know, ease them out the door because music has a profound effect on your mood and your spirit. I hope that my art has that same effect. I can inspire you to feel something.

Building on that question, you also created the iconic artwork for MF DOOM’s ‘Operation: Doomsday’ and designed his first physical mask. Can you share your experience working with MF DOOM and the process behind creating this iconic artwork?

KEO-XMEN: So, I did his DOOM’s first and second masks, this one and the earlier version, which was a cheap plastic one we spray painted. I did many, many album covers for him and his logo, the Metal Face Records logo, Monster Island Czars, KMD, and some other side projects.

Rest in peace, he’s no longer with us in the physical, but it’s still an ongoing process because his wife is continuing to release material and new album covers, and she still calls on me because she knew that Doom trusted me. So there were other albums where he did deal with another label. It wasn’t his own imprint, Metal Face Records, where they had their own in-house art. And he would always try to fight, “No, get Keo. I need Keo to do the artwork”.

Image courtesy of KEO

© KEO-XMEN

Sometimes, they didn’t want to pay, so they used their photograph or whatever, and that’s fine. But I’m really fortunate that I got to collaborate with him on that level because, as I mentioned before, he was a graffiti artist, an incredible artist. The vision, we just clicked. And we were friends. We really bonded on a whole another level to where when he stayed in New York, he would stay at my house.

We’d spend three, four days just vibing, listening to music, talking. It was to where he would sketch something and bring it to me, and boom, I got the idea, you know. All these photographs of him and his brother, Sub Rock, rest in peace, that I had the physical photos. I scanned them in. You know what I mean? Like, that whole process was incredible. Because prior to that, I had done, like, the graphics, and then someone else, the art department, put it all together.

Original Cover by KEO-XMEN

Listen here

This was the first time I had done the whole nuts and bolts. When you create packaging for music, whether it’s a vinyl LP, 12-inch, a gatefold double LP, a CD, or even a cassette, it has to have certain things that you don’t think about as the artwork, a barcode and legal notes, and liner notes, and ASCAP, and BMI, and these things that, you know, I had never had to deal with before. They had people, an art department, to do that. A record label has a whole staff of people. I hand them a raw drawing, and bing, boom, it turns into an LP. So, it was a learning experience for me.

© KEO-XMEN

They had people, an art department, to do that. A record label has a whole staff of people. I hand them a raw drawing, and bing, boom, it turns into an LP. So, it was a learning experience for me. Bobbito Garcia, who is a genius, man, he was really the one that put DOOM and me together, and he’s created so many opportunities for me. I also did the Cenobites, which was another amazing project with Bobbito. That was Kool Keith and Godfather Don. We did some projects that had become cult classics. I had no idea at the time.

You know, it’s funny because I was doing major label stuff like the Wu-Tang and EPMD. I thought that these were side projects, you know, a favour for Bobbito and my man, and, you know. I never thought that these would be what I was famous for. And some of the larger budget projects that I worked on have been forgotten over time. People don’t even know who they are today. You know what I mean.

DOOM process was similar to what I’m trying to do with my painting. In that, he studied the masters and kept it. He would use the same equipment and techniques that the first hip-hop producers and DJs had access to, And you can hear that in the sound. There’s something about that when it’s raw and it’s a little crackly.

It’s the same way I do my spray painting really quick. And if it drips, it drips. Oh well, it’s done. I pretend, in my mind, I put a clock on it. The cops are coming. You got to finish this. I got it. So that helps me to keep it raw, and Doom would spit his lyrics the same way. Yes, he could have done 12 takes and punched himself in and done the ad-libs, and he liked to spit it one time, and it’s good enough.

© KEO-XMEN & Woodbury House

At first, it might sound imperfect or a little off-beat or whatever, but the more you listen to it, it’s like, you know, it grows on you. He was super, super deep lyrically. Only those who know him can really see that there were levels to what he was saying.

There were inferences in every line that related to real life. Even though he might cloak it in comic books or this Toho movie monsters from Japan or some other mythology, he was talking about actual events and people that he had experienced. So the same way I’m grabbing a cartoon character or a comic book superhero, it actually represents something deeper than just that. It’s a time and place. That time and place is still capturing the imagination and the hearts of young kids is incredible to me. Like, DOOM has fans that are just getting hip to it, like it’s the new thing. KMD came out in like 89, it couldn’t have been no later than 1992. So what are we talking about, 30 years? It’s still like brand new. People are still listening to it and finding new levels, and, “Oh, shit. Oh, I just peeped what he said.”

So, and graffiti continues to do that. People thought it was a phase, a trend, a fad. There was nothing really there of substance. But how many other art movements, modern art movements? They’re not 12-year-old kids around the world practicing Cubism right now. This has had a global impact. Whether you like it or not, you can say it’s lowbrow, it’s derivative, it’s, you know, poppy, or whatever you want to call it, street ghetto.

See, street art bothers me because I think it’s diminishing. If you say something is street food, you expect to pay less for it. If you say that’s a street musician, somehow, he’s not as accomplished as a philharmonic musician, as an operatic musician.

They like to talk about street dance. “Well, that’s just street dance. You can’t bring that in the Royal Ballet.” But what does that mean, street? What street are we talking about? Wall Street? Because if I say, yeah, I’m from the streets. Well, most people are from a street. Right? We’re on the street right now.

It’s revolutionary, and it’s scary to the authorities. Because when you have a language that 15-year-old kids can understand and yet you don’t know what they’re communicating, this is the reason why they didn’t let slaves play their drums in the United States. They didn’t let the Indians have their traditional forms of communication because they thought you might be saying, OK, we’re going to start the revolution at 12 o’clock.

So even though we were only writing, you know, “Keo is fresh,” “Keo is the best,” as far as they knew, we could have been writing, you know, “Kill the police.” So, it’s power, it’s the same reason they tried to co-opt hip-hop music. Because anything that has that much influence and has the attention of kids. You know, they had the trials with Tipper Gore, and they were trying to put censorship labels on music. They had congressional hearings in the United States, and it was Frank Zappa, KRS-One, Ice-T, and KMD.

KRS said something, and I’m misquoting him; I’m paraphrasing, but the gist of it was, “If you say that music has the power to negatively influence a child’s behaviour, and that’s what this Court is saying, then you must concede that it has the inverse power”.

So when we were kids, we were using this power of communication we had just to say, “Hey man, I’m here. I’m fresh. I’m the king. I’m the best.” Right? And when you’re a kid with no voice, right, with no money, no means, that’s a powerful statement. That in itself. But once you become a grown man, and now, like I said, we have access to the internet and all this, we have a voice, what the hell am I going to say with it.

So a lot of music I hear today, and it’s great music, I don’t deny it. I’m not knocking it. But what they’re saying is take Molly, Molly, Percocet, buy Louis Vuitton, or even worse, shoot your ops. But where are the positive messaging? Where is that? You know what I mean? And it’s out there. It’s being made. Why isn’t it not getting equal time on the radio? Why is it not being promoted?

I know that this art form that I’ve practiced all these years has an influence. Young kids, particularly young kids from an impoverished background or a broken home, this attracts them the same way it attracted me. So, I have a responsibility.

© KEO-XMEN & Woodbury House

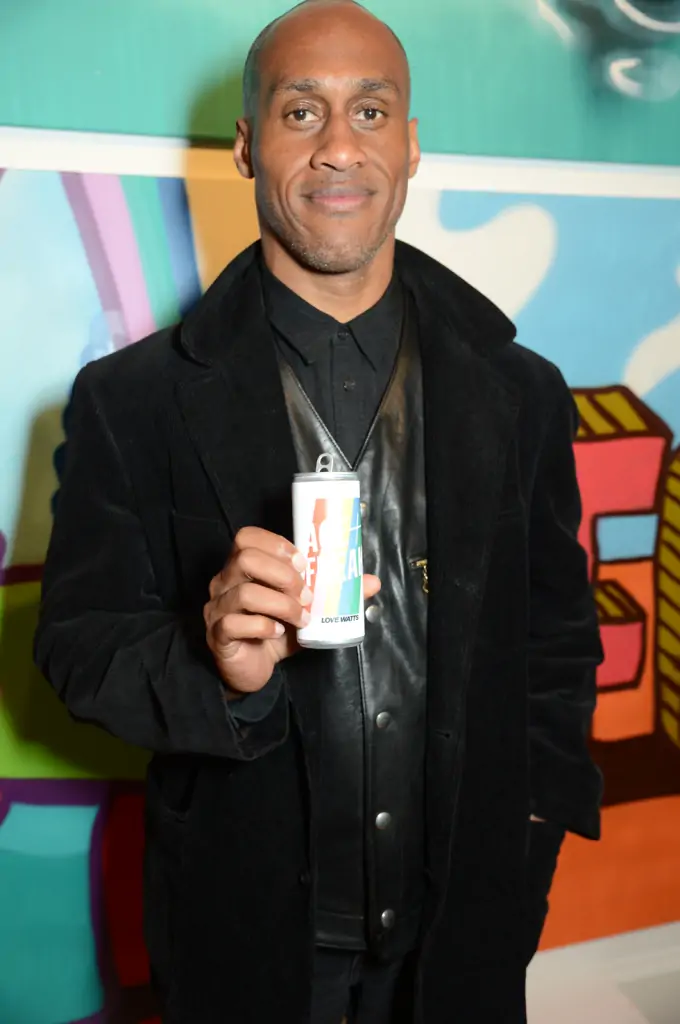

Your exhibition at London’s Woodbury House with renowned curator Jordan Watson, aka ‘Love Watts,’ is highly anticipated. Can you share how the collaboration came about, the essence of the exhibition, and what we can expect to experience?

KEO-XMEN: I said there are good and bad things with this new technology. So the magic of the internet, and Instagram in particular, is that it’s connecting you. If you recall, when I talked about how crazy it would be for you to get whisked off to Hollywood and be in a movie, it was a one-in-a-million chance. Now, people are connected. They don’t have to find you in a malt shop somewhere and say, “I’m going to make you a star.” You have the opportunity to promote yourself.

So many old systems, be that record labels, publishing houses, and galleries, are no longer necessary. So through Instagram, Love Watts found me, I found that. It’s just an organic thing that 30 years ago would not have been possible. In the same way, you can connect directly with your audience; you can also connect directly with collaborators and partnerships. I can reach out to Clark’s or Adidas right now on here, and boom! Hey, send them a DM. Whereas before, you had to know somebody and make an appointment, and maybe they let you in the door. Maybe, just maybe. “Yeah, I got five minutes. Let’s hear your pitch, buddy. OK, next.”

Now, you don’t know who’s looking at your Instagram today, or who’s looking at your social media, or what’s going to come on that. So, I’m a New Yorker; I’m suspicious by nature. If somebody stops you in the streets and says, “Hey, can I ask you a question?” You already did, my man. You keep it moving. Right? But I take every request and DM seriously because you don’t know what may come of it. And yeah, 99% of it is bullshit. It’s opened up the world. Where I only used to have a small circle of trusted friends, guys I grew up with. They came from where I came from.

© KEO-XMEN & Woodbury House

The problem with only associating with people who come from where you come from, do what you do, and have the experiences that you have is you’ll never grow beyond that. People talk about keeping it real and keeping it true, and staying in it. That’s wonderful. But you also have to open your mind. There’s a whole world out there. And you don’t; you no longer need plane fare. I’m talking to dudes in the United Arab Emirates and Australia. Graffiti writers hit me up from all over the world. I got crew members now in Argentina and in, Johannesburg, and in Shibuya. I have friends I’ve never met in person. In fact, when I touched down in London, dudes were like, “Yo! You coming? You need me to pick you up at the airport?” “Yo! I got a wall for you to paint.”

If I were my same old untrusting, kind of guarded person, like, who the f**k is you? I don’t know you. Get the f**k out of my face. You know what I mean? Which was always my attitude; that’s really fear-based. That’s a defensive mechanism. While it may protect you from some negativity, it’s also going to block you from some opportunity.

There are those in my circle, my peers, who would say I’ve sold out. “Oh, he changed up on us. He crossed over to the other side. He’s one of them now. He got fancy. He’s doing interviews.” Should I remain true to what those guys think I should be, or should I see what the world has to offer? Because I’ve already done that. I’ve done my time in the trenches, in the hood, in the subway tunnels, covered in track grease. Now, I’m ready to see what else is out there, you know. I don’t have anything to prove to those cats back there, as I’ve already proved myself.

Dave Chappelle had that great bit about when keeping it real goes wrong. Keeping it real can keep you stuck in the same place you were 20 years ago, 30 years ago. For me, 50 years ago now. So, what have I got to lose by opening up to new experiences and new collaborations? Like I said, all money is not good money, and you have to really research who it is you’re aligning yourself with.

Jordan Watts, Love Watts is solid good people, man. I see what he’s doing, he did it for a long time with no real remuneration. He didn’t capitalize on it. He did it because he truly wanted to expose new artists to the world, create a platform for them. And if you do something, you know, for the right spirit, eventually, the money will come. But that can’t be what you chase.

I do this because it’s my passion. If nobody wants to see my graffiti or buy this painting, that’s fine. I’m still going to be doing it. I was doing it when they tried to lock me up for it. They hated this. So, it may go in and out of favour, I’m still going to be doing it. That’s what I see with a lot of cats who are building these organic grassroots kind of platforms through social media, through the internet, is that. Those who are successful are doing what they really love and not worrying about the money. You build it, the money will come, or it won’t. But at least you’ll be doing what you love.

As someone who curated the first major auction of graffiti, how do you perceive the evolution of graffiti from street art to a recognized art form in mainstream culture?

KEO-XMEN: OK, let me clarify: I didn’t curate that, and I don’t even know if it was the first, but it was a major auction house called Guernsey’s, and they sought me out. I didn’t curate it. They brought me on for my expertise to help curate the thing and bring in other artists. I did not curate that auction. They were going to do it with or without me. They’d have found somebody else to do it. So, I just happened to be the guy, and I was grateful for that experience.

They were a little before their time; had that gone down ten years later, it would have been a lot more lucrative. It was a beautiful event, they made some money. But I was also surprised at some of the things that didn’t sell that were really incredible.Now, those same artists and the same types of black books, sketchbooks, and ephemera are fetching huge amounts of money. In fact, there’s a 50th anniversary of hip-hop auction, wait, Christie’s? No, Sotheby’s right now, and all types of ephemera. They’re selling sneakers for $100,000. You know what I mean? Let alone original Dondi and black book drawings, so they were ahead of the curve on that.

Opening night at Woodbury House

Preserving traditional New York City subway graffiti styles is a mission close to your heart. What challenges have you faced while trying to conserve this art form in an ever-evolving art world?

KEO-XMEN: Well, you know, there’s what’s popular, and I know, I understand. If I wanted a quick buck, I got the formula. You do Mickey Mouse and you put X’s in his eyes. There are a lot of guys doing that, but I would always be a third-rate or a fifth-rate copy of KAWS. Or somebody’s already done that.

I’ve yet to see anybody take traditional subway graffiti and really, without changing it up, without switching it, diluting it to what they think the art world needs to see, and take that all away. So that’s the challenge, if I wanted to get rich quick, this would not be the particular route I take. Again, I’m doing this out of love. It was like the NFT thing. You remember that? People were hitting me up left and right. “Hey, man, let’s do some NFT.” I’m like, what the f**k is that? I saw that it was a Ponzi scheme, a money laundering scheme.

A lot of people made a lot of money. But guess what? That thing crashed, and a lot of people lost their shirts. So, I wouldn’t feel good about just trying to create art for the sake of cashing in. But I’ve never really been a guy who, you know, I grew up poor. We ate welfare cheese. Not that I’m saying I need to be a struggler. But money is not my main motivation. It’s just a tool and doesn’t necessarily bring peace or happiness.

I’ve seen cats get a lot of money and want to kill themselves. So more money, more problems. You know, I’d like to think that I’m mature enough now that I can handle some financial success. I’m open to it. I’m not opposed to it. But that can’t be my reason for getting up in the morning. I want to inspire somebody, man. I want to touch somebody’s spirit, you know, and that’s invaluable. Like I said before, I believe that if you chase that, the money will come. The cream rises to the top.

Looking back on your diverse career, which projects or moments stand out to you as defining milestones?

KEO-XMEN: I have a name, Scotch 79. I have a name, KEO X-Men, and then I have the name my mother gave me, right? So, as Scotch 79, people talk a lot. There have been articles written. They say I was the first White MC, and I don’t know that to be true. There might have been another one. I never saw him. And it was a very small circle back then. If you didn’t meet that person, you heard about him. Somebody say, “Yo, my man from the Bronx, he burned you. He’s better than you.” And you go try to find that dude to battle him. You know what I mean? So, it was a small world.

But I never thought about it in terms of being a maverick. I was just doing what my friends were doing. To me, it wasn’t about “I’m going to be the first white guy to do this.” No, I just was doing what everybody in my class and my friends were into; we loved MCing. They call it rapping now, but we called it MCing. That’s one thing that I’m very well-known for. In the history books, it’s been published many times.

Then of course, in my visual art, I’m probably best known for the MF DOOM album cover, my collaborations with music. I’ve been in a few films, I’ve done some video music videos that were very influential. I’ve also designed a couple of logos that the public recognizes; Everyone doesn’t know it’s me. But when they hear, “Oh, you did that.” it’s something that everyone can identify with. Now, my personal milestones have very little to do with that. Things like when I first hit a subway train. That was a huge thing. Because in New York, in the culture at that time, I could say I got into graffiti when I was eight years old.

But if you were just hitting your schoolyard or your desk or practicing in a book or a little wall in the cut where you could, hone your skills, you weren’t a real writer yet. It wasn’t until you went to the layup with a yard and got your name running on the train that you were official. That was the rite of passage. It’s like you’ve come out of basic training, and you’re in the army now.

So, that was 1979 for me; that’s why you’ll see 79 in a lot of my images. My name is SCOTCH79 because I was writing the year. When it turned to ‘80, which it did that winter, people, back then, when you would meet another graffiti writer, they’d say, “What do you write?” So, I’d say, “SCOTCH.” They’d be like, “Oh, SCOTCH79? I saw that.” So, I just stuck with the 79, and it’s become my number. There’s a lot of numerology around it.

Other milestones for me. I’ve had two lives, you know. So, I had a whole career as a kid. I did all these things that people talk about. “Oh, you were in the fun gallery. That was all the ‘80s, then I kind of disappeared. Now I’m back. I have this second opportunity at life. That, to me, the milestone was when I got clean off of drugs and began to live in a positive way. That ripple effect, then it became, I can now practice my art and it’s with a serious discipline. I can now enjoy my family on a level that affects everything.

When I started getting high as a kid, drinking, smoking cigarettes, weed, and it led to other things, it had a negative impact that affected all aspects of my life. Eventually, my artwork, music, family, school, and all those things had to take a back seat. The same way, when I got clean, all of a sudden, things I thought were lost to me. I was sitting in Rikers Island, bored out of my mind when I picked up a pen and a piece of paper again and started practising my craft, which I hadn’t been doing for many years on the street.

It took me getting locked up to remember who I was, and then other people, other inmates, were like, “Oh shit, you got talent. What are you doing? You don’t belong in here.” I thought about it, I said, “Shit, nobody belongs in here. You don’t belong in here.” So, this brought me back to sanity. I began to do it in jail, and people want you to, “Oh, design a card. I’m going to send it to my girl or make me a tattoo or, you know…” It was like a little trade in there. You get some commissary and some cigarettes.

I began to realize that this thing had the potential to create a means for me to have a different lifestyle. I didn’t have to rob and steal and hustle. I can actually support myself, and now, I’m supporting my family. It’s crazy. I’m super grateful. I should have been dead a long time ago. Then I’m here, even drawing breath is a miracle, but I’m able to have an art show, and the BBC wants to interview me, and people are going to come see my work… Insane. It’s crazy. If you made a movie of my life, nobody would believe it.

Lastly, what does graffiti mean to you?

KEO-XMEN: Graffiti is a term that the media put in us because originally, in New York, we called it writing. The problem with that is that we call ourselves writers, but journalists and authors also call themselves writers. So it was a little confusing. The first people to write about us, Norman Mailer, wrote a book called “The Faith of Graffiti.” I believe he’d written a few articles prior to that book that led up to that. Graffiti, literally, is an Italian term for “to scratch” or “to inscribe”. What you see in ancient Rome, they carved it in stone; that’s not really what I do.

I use the term because everybody knows what it means. But there are many styles of graffiti. There’s gang graffiti. There’s Joanie Loves Chachi with a heart around it. There’s Eric Clapton is God or the Rolling Stones or Disco Sucks, and these things have a different motivation, each of them. There’s racist graffiti and hate graffiti; I could kick over a tombstone and paint a swastika on it. They’ll say somebody did graffiti. I don’t like to be lumped in with those others because the motivation is totally different.

I often say, “I practice traditional New York City subway writing.” But that’s a mouthful. I don’t like to be lumped in with street art. But things have to be classified and have to have a genre. Labels: I’m sure nobody likes to be labelled. The whole movement of punk rock, they didn’t call themselves that. Hip-hop wasn’t called Hip-hop for many years somebody had to say, “Oh, that’s what it is.”

We talked about a tiger, right? And is a tiger in a zoo all fat and lazy? Is it still a tiger? Can you call it that? Does it have the same power? The same spirit. Physically, it’s the same thing. If I take street art off the street and put it in a museum, is it still street art? If I take graffiti and put it on a canvas, does it have the same power? Probably not. No. It was a time and place and location-specific thing.

So sometimes I feel like I’m one of those doo-wop bands that gets together and harmonizes and, you know, ’50s music. When I was a kid, there was nostalgia for the ’50s. We had Sha Na Na and Happy Days. As little kids, though I’m born in 1967, I never experienced the ’50s. We walked around combing our hair a certain way and wearing a leather jacket with the collar flipped up. Maybe we had no idea what it really was like to experience being a greaser in those times. We had the Hollywood television version. Now it seems like there’s nostalgia for the ’70s, ’80s, even ’90s and there are kids who are very young that are interested in this.

But they get the Hollywood version. So they learn how to hip-hop dress from watching “In Living Color“. That was exaggerated; everything for the camera has to be a little. So I feel like it’s my duty to continue to show them the authentic. This is not the sparkly Hollywood version. This is the real. In fact, I get hired for films now to create authentic New York graffiti because what they used to do and what some productions still do is they just have an art department do some fake graffiti. And they say, “Yeah, this is the South Bronx.” And it’s in Toronto.

Everybody knows it. But you go to such care that if you’re doing a period piece set in the ‘40s, you’re going to make sure every automobile parked on the block, every sign, everything is correct. So why would you not take the same care with graffiti? So I’ve actually become a journeyman in the union. It is called the USA Scenic Artists. Right. It’s part of IATSE, a larger group. I get called upon to create period-specific graffiti for movies sometimes.

That’s another thing that I do; Martin Scorsese has hired me, and the RZA has hired me. Guys who know New York, who are there, who give a shit are like, “Nah, I need a real graffiti artist. Get me a real graffiti artist.” So the union didn’t have anyone like that. I became like a specialist. There are lots of other things out there, and they’re all great. I’m not mad at them. I’m not against street art or new styles or evolutions. I’m all for it. But I feel there’s a place for the real thing as well. I want to offer that. I’m not saying it’s the best or the only option. I’m saying I want that to be an option. I don’t want that to get lost.

Know your history. Don’t forget where you came from, right? Those who forget are doomed to repeat. All that wonderful stuff. So I feel I’m doing a service by showing. I’m not the only one. There are other guys out there from my generation who are still practicing that are incredible. I wish them all the most success because I come from a very competitive sport where guys don’t always give each other props.

I’m trying to get past that because even though I might have talked shit about you secretly, I appreciate what they’re doing. So, being true to myself. Even if I don’t like your personality, I’m going to say, “Yo, he’s a great artist.” I don’t have to be your buddy. We don’t have to hang out. But it doesn’t take away from the fact that your artwork is incredible.

I give props where I can, and I always acknowledge who taught me and who came before me. I don’t claim that I invented something that was shown to me. That’d be doing a disservice to the guys who taught me. I try to give credit where it’s due. It’s like, in America, they didn’t appreciate Black music, American Black music, African American music until the British got hip to it and sold it back to them.

So the Beatles and the Rolling Stones were the biggest thing. When they began interviewing the Rolling Stones, Mick Jagger said, “Well, I got it from Muddy Waters.” Then the American public went back and said, “Wait a minute. Who the f**k is Muddy Waters?” They started digging into their own history, realizing that there were gems. So I try to do that. “You know what? If you like me, you’re going to love this. Let me show you who inspired me. Let me show you where I got that from.” Because it’s the least I can do, I owe a debt. You know what I mean? I owe a debt I can never repay.

https://www.instagram.com/keo_xmen

©2023 KEO-XMEN