At the Hayward Gallery, a four-decade survey of Yoshitomo Nara’s work explores solitude, memory and resistance through his iconic, unflinching figures.

Something tender and charged hums beneath the concrete skin of the Hayward Gallery this June. Inside its Brutalist vault—part fortress, part reliquary—Japanese artist Yoshitomo Nara’s universe unfolds not with spectacle, but with stillness. Forty years of work speak less in declarations than in glances. Big eyes. Small gestures. Echoes of unrest. The figures don’t invite you in. They hold your gaze and wait for you to catch up.

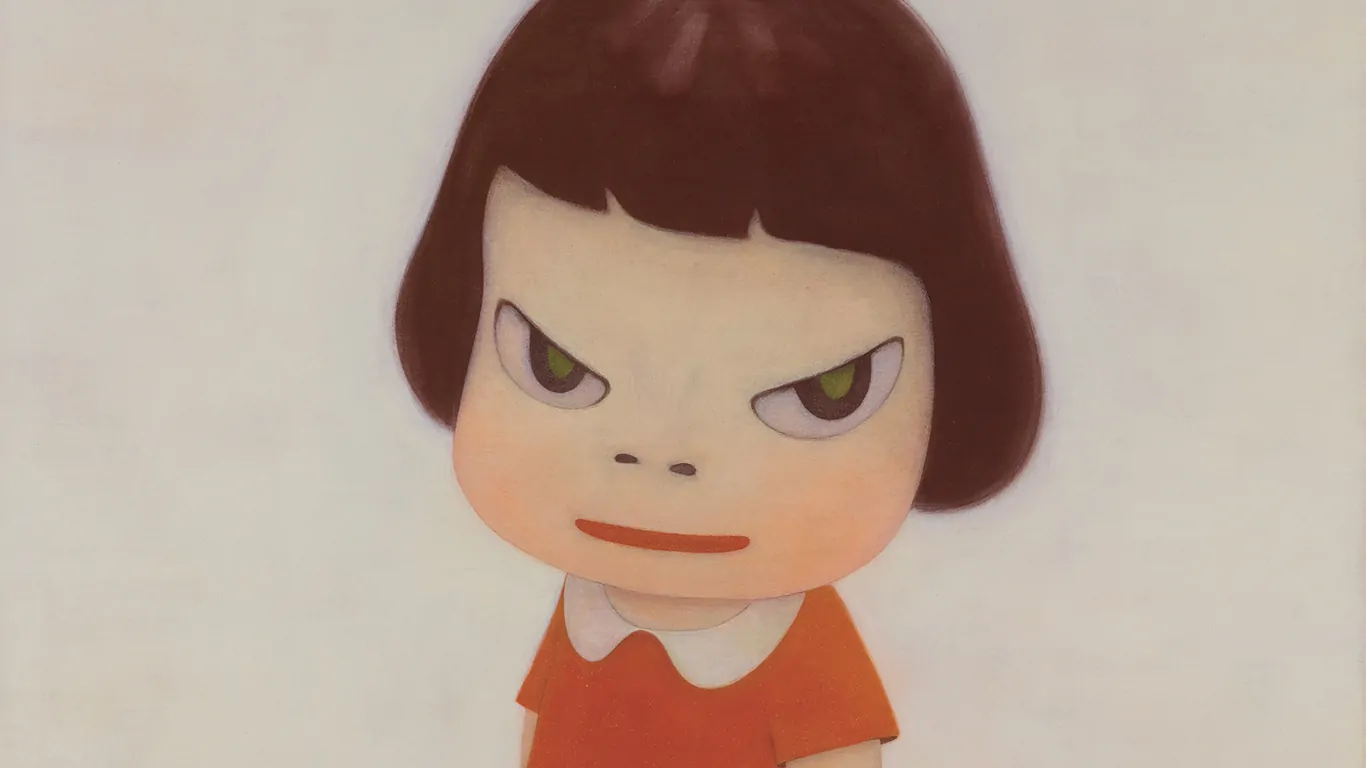

Acrylic on canvas, 227 x 182cm.

Courtesy of the artist and private collection.

This is Nara’s first UK solo exhibition in a public gallery, though his images have long since outgrown borders. On the South Bank, his wide-eyed children—sweet, sullen, eerily self-possessed—confront the viewer with a strange kind of honesty. These aren’t portraits of innocence, but of survival.

They are weather systems in human form: shaped by punk lyrics, German winters, and the quiet radio hiss of a distant American war. “It’s really difficult,” Nara said in a press interview, reflecting on the challenge of placing his work inside the Hayward’s uncompromising architecture.

“But I want to create the impression that the exhibit has been there for a long time… like a permanent exhibition instead of feeling temporary.” But nothing here feels settled. Nara’s world is built on impermanence—on memory, displacement, and the push-pull of resistance and retreat. His work doesn’t ask to be understood. It asks to be felt, then left alone.

The Hayward Gallery has long been one of Britain’s most daring contemporary art institutions, staging genre-defining retrospectives of international visionaries—from Bridget Riley in 1971 to Anish Kapoor in 1998 and Hiroshi Sugimoto in 2023. With Nara’s survey, it continues its tradition of spotlighting artists who challenge form, feeling, and the emotional bandwidth of contemporary art.

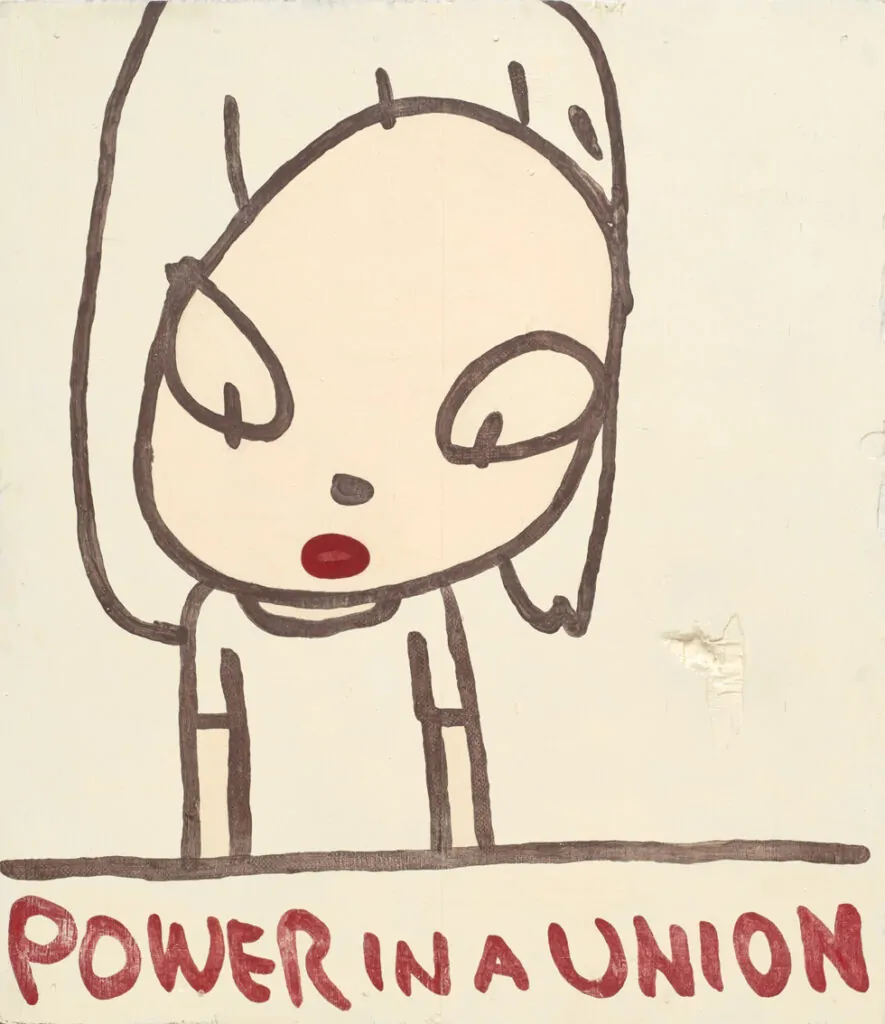

Acrylic on canvas, 100.5 x 91cm.

Courtesy of the artist and private collection.

The Echoes of Aomori

Born and raised in Japan’s rural Tōhoku region, Nara’s earliest influences came not from museums or curated culture, but from album covers and the distant, staticky transmissions of the Far East Network—an American military radio station that played folk and blues for homesick soldiers during the Vietnam War. “I would listen to songs in English I couldn’t understand,” he said in the same interview. “I used my imagination, feeling the songs melodically and coming up with my own stories of what they could be about.”

This sonic drift would later become a central feature of Nara’s art. Paintings like Alone in the Wind nod to Bob Dylan, while This Machine Kills Fascists repurposes the activist bravado of Woody Guthrie’s guitar. But if music offered a soundtrack, it was exile—emotional and geographic—that provided the score.

Germany and the Birth of the Gaze

When Nara moved to Düsseldorf in the early 1980s, he didn’t speak German. Instead, he spoke through paint. Neo-Expressionism, particularly the work of A.R. Penck, gave him a visual language—a way to reconcile the outsider’s gaze with the artist’s inward drift. “I reconnected with that little boy version of myself,” Nara said. “It helped me create a style that was very different from what I was making before—and is what I’m most recognised for today.”

His now-iconic big-eyed figures emerged during this time—not as kawaii caricatures, but more as small muses of resistance. “It never felt good when I would see reviews associating me with ‘kawaii,’” Nara added. Their expressions—sharp, ambiguous, often resistant—stand in opposition to any easy reading.

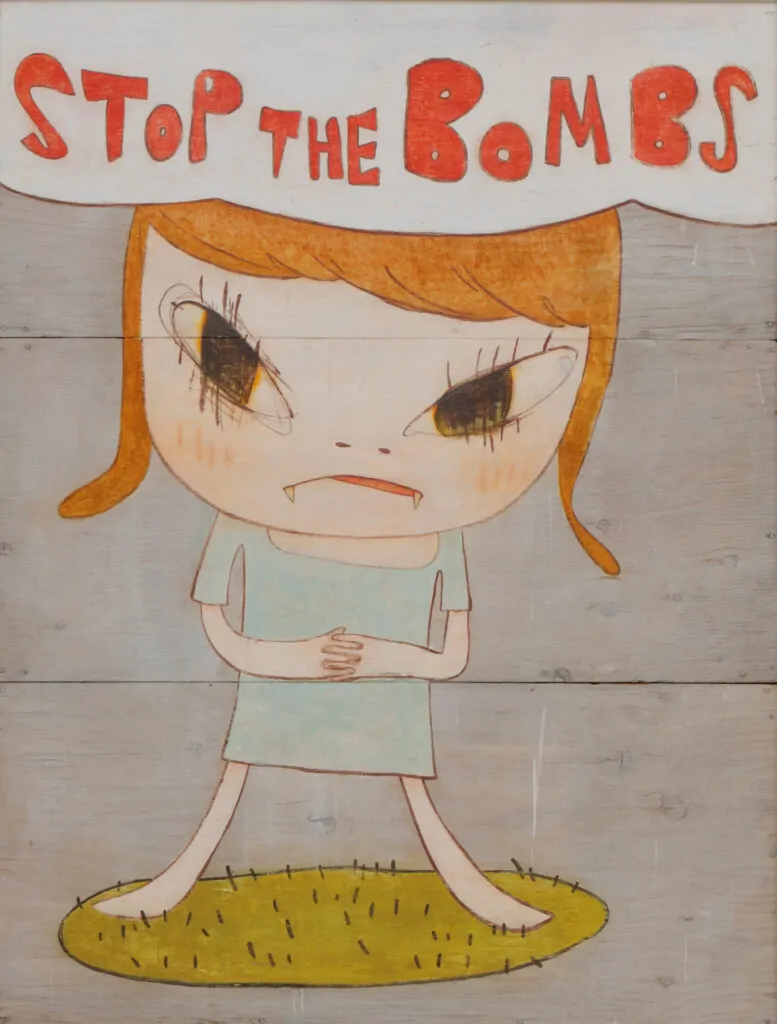

© Yoshitomo Nara, courtesy Yoshitomo Nara Foundation.

Disaster, Memory, and Mission

The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and Fukushima disaster changed everything. For Nara, the regions hit were not abstract—they were personal. “It connected the place I currently live and the place I was raised,” he said. His paintings grew more emotional, more urgent. “I questioned my role in the regional community and felt a strong sense of mission.”

He delivered supplies to devastated villages, held workshops for displaced children, and donated work for relief. “This experience fundamentally changed my viewpoint on life and encouraged me to think about my contribution to society beyond the art world,” Nara noted.

In From the Bomb Shelter (2017), a lone child peeks out from darkness—a metaphor as much for trauma as for tentative hope. More recent works like Midnight Tears (2023) soften Nara’s once-bold lines into ethereal washes of color and uncertainty, as if the emotions themselves had become too fragile to define.

Art as Autobiography, Not Activism

Despite the political undertones, Nara resists being framed as an activist. “I try not to cater to others when I am making art,” he said. “I see my work as self-portraits that allow me to explore my inner world.” Yet this inner world is populated by universal themes: alienation, resistance, memory, home. His work may be personal, yet it’s never insular. “People see their emotions reflected and can access their own similar feelings when looking at the images,” Nara said.

Acrylic on wood, 104.5 x 90.7 x 6 (1.2)cm.

Courtesy the artist.

The Politics of Presence

Unlike many contemporary artists, Nara isn’t preoccupied with the “art world.” “I don’t really think about things like this because I feel like they have nothing to do with me,” he said candidly.

Yet his visual language bypasses theory and speaks directly to something deeper. His characters don’t plead for attention. They occupy. Their stillness demands presence. Their eyes—enormous, uneasy, eternal—return our gaze with questions we’ve learned not to ask. “There is a rebelliousness in me which remains from my teenage years,” Nara explained. “I still feel as anti-establishment now as I did then.”

There’s something fitting about Nara’s presence at the Hayward Gallery, a space that itself seems to rebel against ease. His works don’t just sit on the walls—they feel anchored in the air. “I want them to feel what cannot be seen with their eyes, through what their eyes can see,” Nara said.

© Yoshitomo Nara,

courtesy Yoshitomo Nara Foundation.

Beyond the Canvas

This exhibition is not simply a survey—it’s a soul-map. Viewers move not through time, but through stages of emotion: uncertainty, isolation, defiance, tenderness. It’s a journey that reveals as much about us as it does about Nara.

In an era where feelings are filtered, sponsored, and served on demand, Yoshitomo Nara dares to paint like someone who actually felt things. Remember that? Being small, not as a branding aesthetic, but as a real, inconvenient truth.

Being alone—not “self-partnered,” just plain lonely. Hearing a song in a language you didn’t understand and giving it your own tragic translation, because your 9-year-old heart demanded meaning. Nara looks the world in the eye—not to perform resilience for likes, but simply because he never learned to look away.

Yoshitomo Nara at The Hayward Gallery opens on the 10th of June, 2025 until the 31st of August, 2025

©2025 The Hayward Gallery, Yoshitomo Nara