Shanghai-born and New York-based curator and writer Xiaoyu Weng, pronounced (sh-ih-ow-y-uu w-eh-ng), boasts a track record that reads like a who’s who of accomplishments.

Weng’s experience as a curator is nothing short of impressive, encompassing roles in both institutions and independent projects. She has worked with over 300 artists, practitioners, and organizations to organize exhibitions and programs across all continents. Additionally, she has penned and published numerous essays on contemporary art, visual culture, and curatorial practice.

Image courtesy of Xiaoyu Weng

Most of my curatorial focus comes from continuous and ongoing conversations and collaborations with artists and other practitioners

Xiaoyu Weng

In 2016, Weng curated “Tales of Our Time” at the Guggenheim in New York. This exhibition featured Chinese artists such as Chia-En Jao, Kan Xuan, and Sun Xun, challenging traditional notions of place by highlighting underrepresented cultural and historical narratives. The artists focused on diverse locations, from their hometowns to remote areas, exploring abstract concepts like territory and utopia. This approach presented China not just as a country but as an idea open to reinterpretation. The exhibition was inspired by “Gushi xin bian” (Old Tales Retold, 1936), a book by the renowned modern Chinese literary figure Lu Xun, who retold ancient myths and legends to criticize society, redefine history, and highlight the problems of his era.

Weng’s journey to becoming a curator was deeply personal, ignited from an early age as she observed her father’s conversations with fellow artists in his studio, absorbing the wisdom of collaboration. As a curator, Weng values the collaborative wisdom she witnessed in her father’s discussions. This is evident in her ongoing dialogues and partnerships with professionals from various fields, including scientists and engineers. With a focus on examining issues related to globalization and the intersection of art, science, and technology. As an immigrant, cultural dislocation and alienation are not just recurring themes in her curatorial work; they are deeply ingrained in her thinking and interactions with art, artists, and her practice.

In her latest curatorial project at Singapore’s STPI Workshop, Weng collaborated with renowned Korean artist Lee Bul, known for her multifaceted practice. The exhibition explores modernity, technology, and utopia through printmaking and unconventional materials. In short, Weng is a curatorial force to be reckoned with in the art world. We caught up with her to delve into her curatorial practice and recent collaboration with Lee Bul.

Hi Xiaoyu, please introduce yourself to those who may not be familiar with your work. Share your journey into the arts and your decision to become a curator?

Xiaoyu Weng: My name is Xiaoyu Weng, and I was born and raised in Shanghai. I have been a curator since my time in college. I was interested in contemporary art at that time and started working as a gallery assistant in the 798 Art District in Beijing. After that, I pursued a Curatorial Practice degree from the California College of the Arts in San Francisco and professionally launched my career in the Western world after receiving my degree.

My curatorial work has always focused on the issue of globalization and in recent years, the intersection between art, science, and technology. As an immigrant, cultural dislocation and alienation are themes that are hovering or permeating in my thinking and interaction with art and artists and practice. I don’t think that this is a thematic pursuit in my work, but something that is in the DNA of how I look and think at art practices, and also its relationship with the world.

Importantly, my father is an artist, and I grew up in his studio. It’s part of my everyday life, and my dad has integrated his life and work together. I remember vividly evenings where he and his artists and intellectual friends would debate over dinner and cigarettes. I would always fall asleep on the couch, and I have these very intimate memories and warm feelings of my dad trying to carry me and put me to bed. I also did a lot of drawings and sketches as a kid. There are works of my father and I making portraits of each other and my documentation of the scene of these debates and gatherings. So, for me, becoming a curator is very personal and closely connected to emotions and the fact of being human.

Your curatorial practice, with its broad focus on globalization, art, science, and technology, and its consideration of ecological and environmental changes through feminism, identity, and decolonization, is intriguing. Could you elaborate on how these elements shape your curatorial practice?

Xiaoyu Weng: I had touched upon this in my answers to the previous question. But at the same time, my interests and research area has evolved and developed over the years, and some of them is a running thread. While others continue to get informed of the interesting practice that contemporary artists have put forward, most of my curatorial focus comes from continuous and ongoing conversations and collaborations with artists and other practitioners. The boundary between disciplines which was well established during the imperialistic pursuit of knowledge in colonial times has gradually disintegrated, and I now have the opportunity to learn many new things from scientists, engineers, and people from different disciplines who are interested in art and having a discourse.

This was the early motivation of why I wanted to look at these fields interconnectedly, and I think these are the important issues in the forefront of our social and political reality. My practice always has that built in. It’s almost a default that I look at art that has a social or political impact. Art for me, is not just aesthetic experiences, aesthetic representations of beautiful things, or pleasant experiences. It has to stimulate thought and questions.

I also think that with a world that is increasingly becoming more localized and nationalistic driven, even with the rise of the Internet and the digital community we are facing a conservative political environment — these issues and topics become even more urgent and necessary in our future undertaking.

Building on that, how do these themes inform your approach to curating?

Xiaoyu Weng: My previous answer has touched on this question. I would like to add that my work as a curator is made up of different aspects, such as writing, making exhibitions, researching, putting together programs, and organizing gatherings. These aspects have very different functions and purposes, and outputs. In the case of making exhibitions, I’m curious of always trying to think outside of a traditional art or museum context and how can we borrow and reference visual elements, aesthetic formations from different disciplines, and how that can contribute to how art is being displayed and interpreted.

In terms of my writing, I rarely look into the reference in classic art history, because that is, in my opinion, written in a very narrow and uneven point of view, and it’s not very inclusive and diverse. For me, many of the interesting references and critical thinkers are come from other disciplines like anthropology and science.

How has your journey from Shanghai, through your educational experiences in Beijing and San Francisco, influenced your curatorial style and your perspective on art?

Xiaoyu Weng: I’m an immigrant, and I’ve lived in many different parts of the world that have vastly different cultural histories and traditions. This helped me in thinking globally and also thinking in this position and experience of the in-between. I do see myself often caught in the dilemma of being lost in translation or being the only person who understands something from different sides of the story while being incapable of communicating to either side.

This feeling of alienation and being stuck in articulating constantly oscillates from one extreme to the other in my practice and daily life, and I try to communicate this in my practice and work. I also find a lot of solidarity and community with artists, intellectuals, and cultural practitioners that share similar experiences. I really find that it is crucial in continuing to strengthen mutual understanding amongst people, but sometimes I do feel that there is a ‘glass wall’. On one hand, it can be frustrating, but on the other hand it’s something that motivates me to continue to do my work.

Photo courtesy of the artist and STPI – Creative Workshop & Gallery, Singapore.

What are the biggest challenges you face as a curator at the intersection of art, science, technology, and social issues?

Xiaoyu Weng: There are many challenges, with one of the biggest being trying to create more meaningful exchanges among these different fields, and how to help intelligent and creative people think outside of the box and create impactful and meaningful collaboration among them.

Oftentimes, we still see that not so great art is a simple visualization of some scientific discovery or data. Also, science still has a very difficult time to incorporate the ethical and emotional aspects of thinking through some world issues, and technology is pretty much trapped in this capitalist machine.

I really hope that in the coming time, we are able to create more exchange among these fields and minimize limitations.

Having worked in diverse cultural contexts, from North America to Russia and China, what are the primary challenges and opportunities you’ve encountered in curating art across these different landscapes?

Xiaoyu Weng: I’ll discuss opportunities first. It’s definitely rewarding and fulfilling to present contemporary art to different cultural contexts where I’ve helped to overcome so-called cultural stereotypes of place and identity. It’s also a powerful tool to overcome the politics in that nation state that shapes our world today. I’m trying to enter each context with an open mind to learn and to understand what is at stake and being presented.

In terms of challenges, there is this diminishing tendency of optimism over globalism and global connection, not surprisingly, because of all the side effects and negative economic, political, and social consequences that have been brought forward by globalization and the unequal distribution of wealth and resources, so people have become more sceptical of what kind of a world we are marching into. So I think this is something definitely worth reflection and further investigation together with artistic minds.

You’re known for organizing groundbreaking programs. What’s your key to creating trend-setting and boundary-pushing exhibitions in the contemporary art world?

Xiaoyu Weng: Thank you for this comment, I feel very flattered and honoured. I think in terms of thinking about ground-breaking programs, one angle is really about how I worked in museum and institutional contexts. Traditionally, contemporary art programs in the museum context can be very limiting and also conservative because of many administrative and management constraints and bureaucracies. So I think in that sense, curating in an institutional context is also about battling with these bureaucracies, and coming up with creative solutions to implement projects and to realize artists’ visions. It’s not always easy and comprehensible for different parties and different shareholders in the institution, so that is definitely something that requires patience, communication, and leadership skills.

And in terms of working outside of institutional contexts, for example, the biennial I was curating, I think that comes from my intuition and sensibilities in close contact with the artists and what they’re talking about. I’m very much a strong advocate for artists, and I’m also a curator who really enjoys working on the ground, doing a lot of studio visits, and really engaging in in-depth conversation with artists, so I think this definitely has been very helpful.

Photo by Toni Cuhadi. Image courtesy of STPI – Creative Workshop & Gallery, Singapore.

Regarding your latest exhibition Lee Bul: Prints with Korean artist Lee Bul at STPI Creative Workshop, which explores modernity, technology, and utopia through printmaking and unconventional materials, could you share more about the exhibition’s core themes?

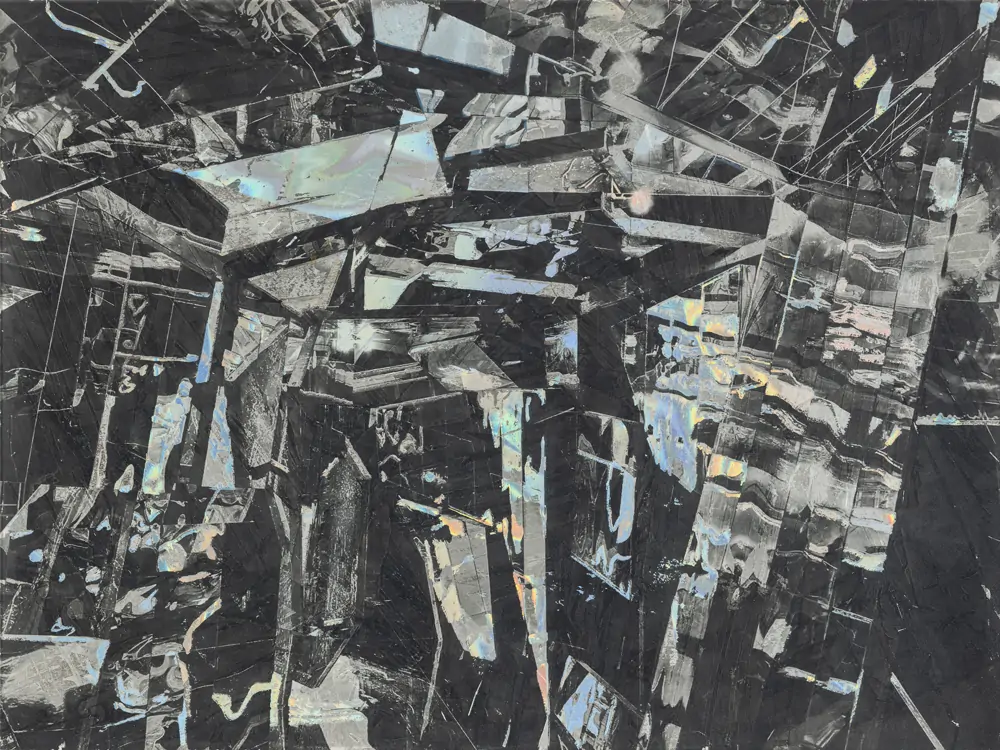

Xiaoyu Weng: Yes, of course. This is the first time that Lee Bul has ventured into making prints with the support and collaboration from a very esteemed institution that specializes in print printmaking. The exhibition essentially is an extension of Lee Bul’s practice and some of the fundamental and core themes that she explores in her long and established career, that ranges from ideas and thinking through the contradictions and dilemma of pursuing utopia in human history, to her famous figure – an image of a cyborg – and also to the symbolic aspects of the utopia pursuit.

I think one key theme that I had drawn out of the collaboration and conversation with Lee Bul is this idea of smithereens, which is implemented and manifested in many of her engagements, interest, or obsession with the material of glass and mirror, and reflective materials, oftentimes shattered, broken, placed in angles or have refractures and reflections. This idea of smithereens came from Zen Buddhist teachings. The original saying goes: when you appear in front of a mirror, you see the image of yourself, but what happens when a broken mirror is placed? This is a metaphor to describe how an image cannot be represented when it’s broken in the first place.

This is something I encountered interestingly, not quite through my East Asian upbringing, but through the French philosopher post-modernist, Jean-François Lyotard, on his work writing and curating for this exhibition called Les Immatériaux at the Pompidou Center in 1985. The exhibition became one of the most influential shows despite its negative reception at the time.

Lyotard was truly ground-breaking for me because he had placed traditional art objects like works by Korean avantgarde artist Nam June Paik, in juxtaposition with the newest invention of materials, the internet, the computer, in the car, etc. The show essentially is about the intersection of art and technology, and how one can help the other to think through these issues. One key subject matter that Lyotard wanted to address is this idea of the inscription and idea of recording, and by extension, history writing. And in his opinion, the Western epistemology or framework of technology has the essential task to record. Think about how we invented hard drives, and the computers – this is to help preserve history.

In this Western way of framing reality, it always wants to preserve everything in totality; there is this complete narrative. This for him, was very limiting, and there are certainly limitations in pursuing this approach. That’s where he became intrigued by this Buddhist thinking of smithereens. What if you just cannot capture everything in its totality? Does this image of totality also represent a kind of eagle? Kind of like a European way of framing the world.

Through all these contemplations, I found it very intriguing and became interested to connect that with Lee Bul’s thinking on utopia – how all humans desire and obsess about utopia, creating this grand narrative, that it is actually a very troubled situation. That became some of the key elements I wanted to build in relation with the show.

Expanding on that, how was collaborating with Lee Bul during the ‘Prints’ exhibition? Were there any significant synergies and creative dynamics? How did this partnership impact the exhibition’s final outcome?

Xiaoyu Weng: The collaboration was fantastic. Despite knowing Lee Bul’s work, I have never really directly worked with her. I’ve always admired her practice, and really think and consider her as a pioneer, and also a very influential figure as a female artist from East Asia.

I think the synergy that came from our collaboration is how we think about ideas of cultural influences, the so-called Western East, and the kind of references that we are interested in and were brought up and educated on navigating these different cultural contexts.

Photo by Toni Cuhadi. Image courtesy of STPI – Creative Workshop & Gallery, Singapore.

I definitely think that we created a bond in thinking through these issues and she is very happy with the writing, my interpretation and framing of this idea of smithereens. It was a very collegial, creative, fun, and inspiring process. Lee Bul originally wanted a very classic exhibition because these are prints, not installations or large-scale sculptures. But I suggested to incorporate some of the elements into the show, not necessarily as part of the work, but part of the context and architecture and environment.

That’s when we decided that we would have a reflective mirrored floor in one of the galleries, paying homage to her long-term interest and love of this reflective material. It turned out to be something that everybody really loved. There’s also another small element – the featuring of zeppelin – a symbolic image that recurs in many of Lee Bul’s work. The zeppelin repetitively shows up in the show; it’s like a little storyteller and a character that connects different sections and bodies of work in the show.

With your extensive experience and insights, what are your predictions or hopes for the future of art curation, particularly with the rise of digitalization and global connectivity?

Xiaoyu Weng: Great question. I have some first-hand experience discussing generative AI and AI curators, which is certainly a very interesting topic. People are already writing algorithms and training AI to be curators and to do the curation. I’m not against that. I think it’s something that you can’t really resist, it’s just happening. And with that said, it has actually raised the bar of curating, and raised the bar of our curation to really think outside of conventional structures.

It’s not just about creating some keywords to connect the themes; it’s not about selecting works to fit the themes, it’s not just about coming up with a title to group all the artworks together. It’s something much more complex, much more creative, requires much more care, and much more collaboration. Attention into creating frameworks that is diverse, inclusive, non-conventional, critical, is also needed to challenge the norm. I am very curious about how AI would get rid of the bad curations. That’s a more interesting topic for me to think about.

Have any artists particularly impressed you, and are there any you would consider collaborating with?

Xiaoyu Weng: There are many artists that inspire me — both historical and contemporary. I don’t like to pick my favourite as it changes over time. There are so many artists that I would love to collaborate with, and have learned so much from, but currently, I have just completed an essay on the practice of artist Gala Porras-Kim, so she’s on my mind. We have collaborated before, but I would be happy to collaborate with her again.

Lastly, what does art mean to you?

Xiaoyu Weng: Art means so many things to me. First and foremost, it’s an engagement, an undertaking, a process of becoming that resists the norms of injustice, historical trauma, and unfairness and many boring and interesting aspects of this world.

It’s a conceptual and emotional apparatus for freedom. Art is about curiosity. For me, it is a way to actively engage with the world and connect with people to look at the world in very different ways. It means a lot, but ultimately, it’s also always personal and always intimate. It always offers momentous enlightenment or a feeling of connection when one sees a piece of art or when one interacts with an artist.

http://instagram.com/xiaoyuxiaoyuxiaoyu

©2023 Xiaoyu Weng