Hauser & Wirth curator Isabella Bornholt explains how a rural farmhouse in Somerset provides culture in contrast to London.

There has been a distinct shift in attitudes towards London’s place in the art market. Some have

claimed a stale over-saturation of ‘safe’ shows – often paintings. In an age where strenuous PR and social media efforts have challenged the necessity of physical spaces, risk-taking is essential in cementing the brand of smaller galleries.

The state of economics hasn’t just discriminated against smaller galleries in London’s art world; however, recent closures of leading galleries such as Simon Lee and TJ Boulting have sent ripples throughout the city. Markets and tastes have shifted along with economic states – no one seems to understand what’s going on.

For Hauser & Wirth – one of the world’s leading galleries, risk-taking has always played a role in

their rapid success. Their recent Somerset show, An Uncommon Thread, curated by Isabella

Bornholt, continues this trend.

A gallery location in a rural farming town of just 2,800 people challenges the quick-moving, citycentric model. London suffers the consequences of its relentless pace. One day you’re hot, the next day you’re not. Now, it’s not uncommon for galleries to be in small towns or rural locations – Gstaad in Switzerland has a population of just 9,000 yet houses Gagosian, Patricia Low Contemporary, and Hauser & Wirth themselves. Bruton, Somerset, is a rural farming town with a population of 2,800. So why does this work so well?

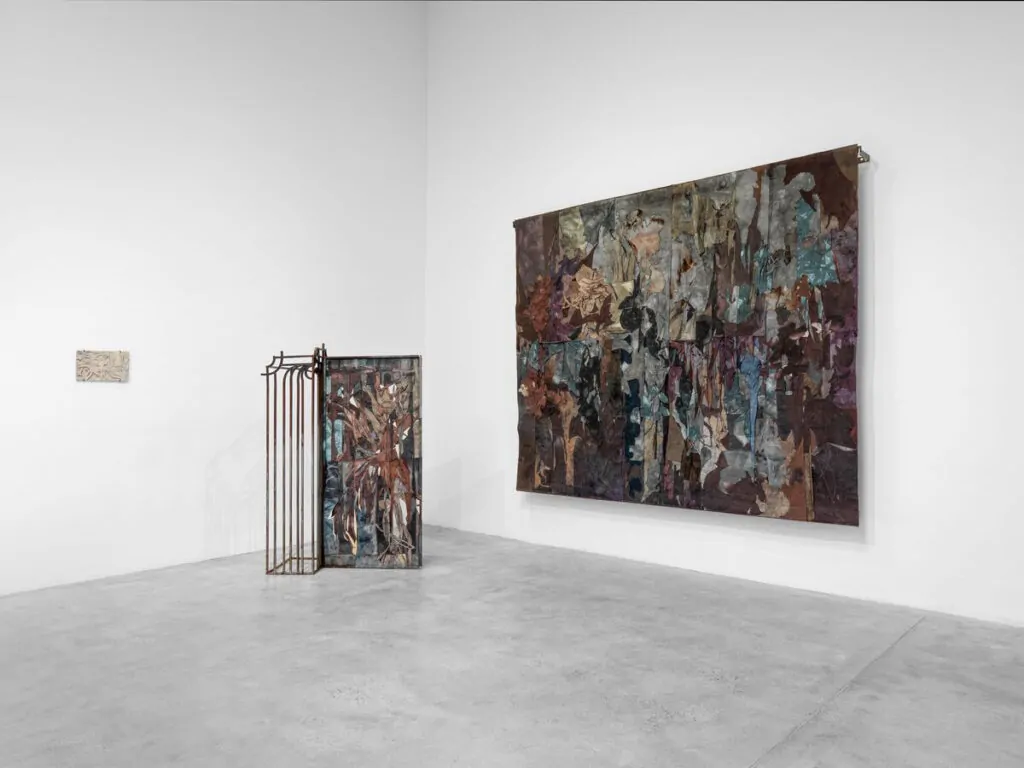

Courtesy the artists and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Ken Adlard.

I’ve visited Hauser & Wirth Somerset twice in the last month. Every time I go, I’m astonished by

the number of families, elderly couples, and leisure-goers touring the gallery alongside the ‘arts

crowd’. I’ve never personally witnessed this in their London locations.

If we think of regional institutions, generally they are doing exhibitions with well-established or

dead artists. Very rarely are mid-career or emerging artists brought to these regional areas.

Household names such as Andy Warhol or J.M.W. Turner attract visitors willing to pay or donate,

especially in areas with lower casual footfall. So why does this risk in Somerset work?

“There is a freedom felt in Somerset. Considering the simple contrast even in rental prices, the

ability to show emerging and mid-career artists in London is trumped in comparison by large spaces in regional areas,” Bornholt states. And whilst this seems obvious on reflection, rarely does one acknowledge a large-scale regional approach – especially in a city-centric international market. With a farm shop and multiple bars and restaurants on site, their Somerset location fosters a sense of community that feels almost impossible in London. And, sadly, it is.

It goes without saying that smaller galleries couldn’t risk packing up and relocating to Somerset— or any rural farm location, for that matter. However, larger galleries with the funds should be taking the risks that smaller galleries can’t afford to. Large galleries could generally use rural locations to ‘test’ emerging artists with local communities, who tend to be more responsive and vocal than Londoners.

I’m not stating that’s what H&W Somerset necessarily do, but risk-taking can undeniably occur more prevalently in large spaces outside of London. Showcasing new experimental mediums comes with less financial pressure in rural locations—a potential indicator of why this model works so well. “Even if the drive is an hour away for some, people make the trip.

The space isn’t just a location for collectors and art lovers, but a place where the community can engage in contemporary art without having to travel to London. Even if you aren’t versed in art history or visual references, visitors to our farm shops and bars are invited to engage with our artists, hopefully not feeling intimidated by the pretense of fine art, as can sometimes be the case in London,” Bornholt expresses.

Courtesy the artists and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Ken Adlard.

From firsthand experience, I truly echo this. My friend’s mum drove us to the gallery (she’s a local but had never visited) and was blown away by the display of art she hadn’t seen before. Seeing new materials (Isabella’s latest show featured no paintings) was a profound experience for her, and I noticed others feeling the same.

Although regional locations do get shows featuring renowned artists, as stated earlier – they’re usually dead or well-established. Even that alone can come with a level of intimidation, creating an expectation to ‘understand’ the seriousness before entering.

Yet in Somerset, showing completely innovative techniques from relatively unknown artists (at least to farming villages) creates access in a way that’s typically reserved for Londoners like myself. Showing emerging artists priced up to £20,000 may not be so viable in Mayfair for example, where monthly rent can reach six figures. It may work for a large warehouse in East London, but unless the artists themselves are on an intense trajectory, central London feels like a distant dream.

Courtesy the artists and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Ken Adlard.

Curator Bornholt states: “We wanted to collaborate with galleries who were taking risks and

pushing boundaries with their artists… we get to showcase emerging and earlier-to-mid-career

artists outside London in an almost museum-like setting.” This simple risk, enabled through the

gallery’s global successes, is such a crucial element of why Somerset does so well. Locals feel

involved – invited even, and are able to participate in city-derived art scenes without facing tube

confusion or rancid pollution. Instead, a slice of contemporary culture is placed on their doorstep, with an added bonus of local ciders, cheeses, and produce awaiting their visit.

In an over-saturated city, talent unfortunately doesn’t always equate to success. The ability to stand out also depends on suitable space: a work might look terrible in a cramped Hackney group show, but a huge wall in Somerset allows for a significant museum-like setting – a much cleaner way for visitors to absorb perhaps more conceptual artworks.

Courtesy the artists and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Ken Adlard.

Wrapping this piece together, I want to question the large galleries making millions per month yet producing boring, uninspiring shows – ones that may sell out to collectors but do nothing to push the boundaries of art.

We all have our opinions on large galleries, but I really want to stress the difference in approach that Hauser & Wirth are taking. They could easily rely on showing guaranteed names, yet they continuously invest in developing the wider art ecosystem. Their expansive list of niche locations and residency programmes, their community learning models, their dedication to hospitality, and their genuine sincerity – all mark how a globally leading gallery should champion art beyond commercial incentives.

I urge more curators, gallerists, and so-called ‘champions of art’ to actually push boundaries – stop hiding behind commercial staleness or blaming the ‘terrible art market’ to excuse a lack of

curatorial ambition.The UK needs to remain a risk-taker in art, and while things may seem bleak,

we can look to curatorial efforts from those such as Isabella Bornholt, with a bit of hope that things might get exciting again.

©2025 Hauser & Wirth