Through a landmark retrospective in Hong Kong, curator Valerie Wang reflects on the transcendent philosophy behind Hoo Mojong’s art — and what it means to reframe modernism through an Eastern lens.

In a world of fast-paced visual culture and crowded international art calendars, Valerie Wang chooses a different path—one marked by reflection, clarity, and conviction. As the director of the BAO Foundation and Zhi Art Museum, Wang has become a leading voice in bringing overlooked Eastern narratives into global conversations.

Her latest curatorial project, Objects of Play: Hoo Mojong Centennial Retrospective, opens not only as a long-overdue recognition of a singular artist, but as a wider meditation on history, memory, and artistic virtue.

The retrospective, the first major exhibition of Hoo Mojong’s work in Hong Kong, takes place in a city long shaped by cultural intersection. It is a fitting setting for an artist whose life crossed borders—from Ningbo and Shanghai to Taipei, São Paulo, Barcelona, and Paris—and whose work eludes easy categorisation.

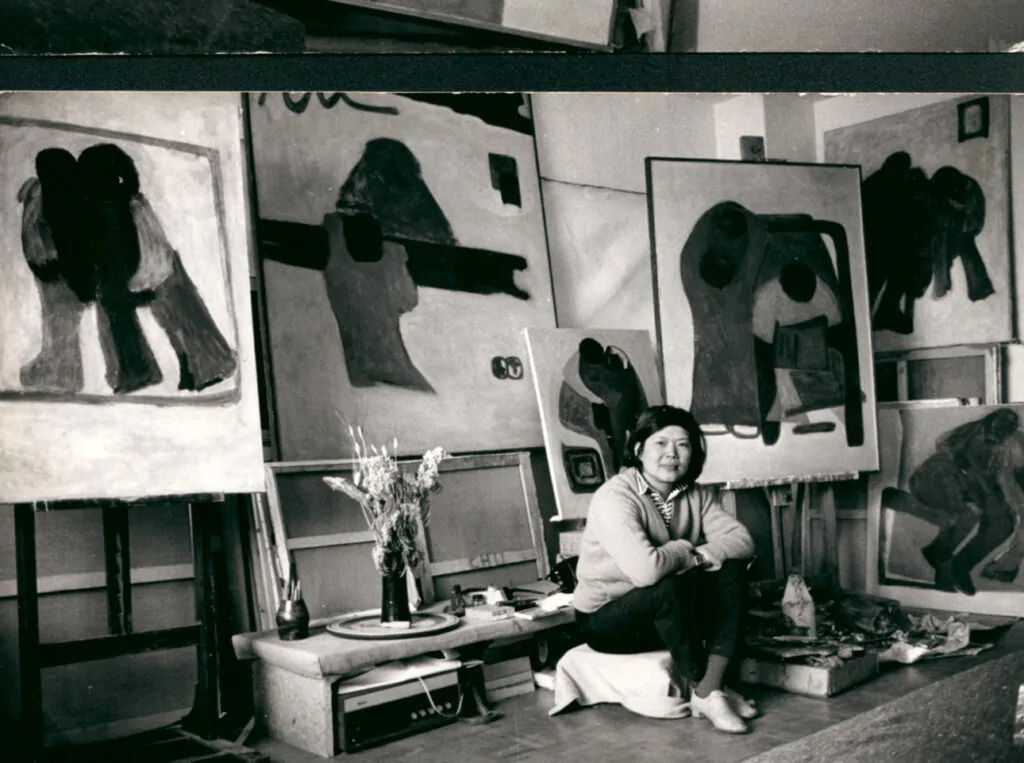

The Opening of Objects of Play: Hoo Mojong Centennial Retrospective.

Courtesy of Bao Foundation and Asia Society Hong Kong Center.

I believe institutional exhibitions should always go deeper—grounded, visionary, and capable of inspiring a recalibration of art history

Valerie Wang

“The most valuable philosophy in Eastern aesthetics literally is ‘Tian Ren He Yi’ (天人合一), means the human are harmoniously living as one with the Universe,” Wang explains. “Hoo is such an artist that achieve this peak. The name Objects of Play implied this term. She becomes what she painting, forgetting herself in artmaking, like children playing fully devoted. Hoo’s paintings are not made but artifacts of a state of being.”

Organised around five verbs—Roam, Play, Refine, Return, Etch—the exhibition maps not only Hoo’s biography, but the evolution of her artistic language. These verbs speak to experience as much as process, and to a way of working that, as Wang puts it, is “extremely ancient, yet contemporary, and global since thousands of years ago since human being began to create art.”

The exhibition also opens during Hong Kong’s “Super March,” coinciding with Art Basel. Wang sees this as a moment to distinguish institutional depth from market spectacle. “Institutional exhibition should always go deeper, being firm and inspiring the vision, leading the reshape of art history,” she says. “This Hoo’s exhibition could be a quiet earthquake. The more chaotic the art fair, the louder Hoo’s silence resonates.”

Valerie Wang is Director of the BAO Foundation and Zhi Art Museum, specialising in global curatorial practices rooted in Eastern aesthetics and Asian art. She holds a Master’s Degree in Aesthetics from the Philosophy Department of Peking University. A former senior reporter at China Central Television and specialist at Sotheby’s and Christie’s, Wang now leads research-driven curatorial initiatives and institutional collaborations. Her exhibitions include Fantasy Luis Chan: A Retrospective (2018), Wei Ligang: Universality (2019), and The Art of Escape: Gao Yu (2023). She also founded the Open East: Asia Museum Forum in 2019, a platform to advance the re-narration of Asian art in the international context.

With Objects of Play, Wang not only reintroduces a long-neglected figure, but raises larger questions about modernism, memory, and the place of Asian women in the global art canon. “We wish to redress the eternal power and value of art in an everchanging world,” she says. “Hoo poured her whole life into her art. She was a thoroughly genuine person, with strong looks, powerful hands, and a steadfast and generous nature… She remained true to the essence of life, capturing with her brush and burin a beauty that transcends time and space, culture context and political turbo.”

Your curatorial approach often bridges Eastern aesthetics with global narratives. How did this philosophy shape the creation of Objects of Play: Hoo Mojong Centennial Retrospective?

Valerie Wang: The most valuable philosophy in Eastern aesthetics literally is “Tian Ren He Yi” (天人合一), which means humans are harmoniously living as one with the Universe. Hoo is such an artist that achieves this peak. The name “Object of Play” implied this term. She becomes what she is painting, forgetting herself in artmaking, like children playing fully devoted. Hoo’s paintings are not made, but artifacts of a state of being.

I think that approach is extremely ancient, yet contemporary and global, since thousands of years ago when human beings began to create art. In an effort to reshape the multi-modern historical perspective, this retrospective marks the centenary of Hoo’s birth and is the first major show dedicated to her works in Hong Kong, a cultural and commercial crossroads between Asia and the West for well over a hundred years.

The date and venue have great symbolic significance, as they offer an occasion to re-examine questions of diversity in global modern art history with Hoo as a case study, and to reconsider, with a century’s hindsight, the position of Asian women in international modernism.

Private Collection

You’ve structured the exhibition around five verbs. Could you walk us through this concept, and explain how it charts Hoo Mojong’s artistic and personal evolution?

Valerie Wang: Hoo’s works are like the artist herself: supremely simple, quiet, profound, and honest, shunning showiness and excess. Hence, the exhibition curation is structured with five simple verbs used to name the chapters—five chapters that span the last 100 years:

• ROAM: The Lone Traveller – Hoo Mojong’s life spanned multiple cultural contexts. Born in Ningbo and raised in Shanghai, she later lived in Taipei, São Paulo, and Barcelona before settling in Paris. Her early years of travelling the world forged an independent and multicultural background that shaped her artistic vision.

• PLAY: The Light of Paris – Reaching its peak during the 37 years in Paris. She developed a unique modernist language in France’s vibrant artistic atmosphere while honestly finding herself in the bustling Paris modern art trend.

• REFINE: The Eternal Everyday – Drawing inspiration from ordinary objects, discovering the divine in everyday life.

• RETURN: The Flowers of Home – Reconnecting with her Eastern heritage, redefining her spiritual ties to her origins and hometown after half a century of living overseas.

• ETCH: The Queen of Copperplate – Breaking the boundaries of traditional printmaking, pioneering new visual expressions between East and West.

By walking through these five chapters, we can come to the conclusion that, without a doubt, Hoo Mojong was a trailblazer in her day, an unrivalled figure among 20th-century Asian women artists. Her exceptional legacy, eloquent yet unassuming, transcends time and remains vitally contemporary today.

What initially compelled you to engage with Hoo Mojong’s work? Which aspects of her life or practice felt most urgent to reintroduce to an international audience today?

Valerie Wang: I first noticed her works in an Aye Gallery exhibition in Beijing about 10 years ago. At that time, Asian modern women artists were very rare in both the primary and secondary markets. The unique tone of her work aroused my curiosity to do more research on this special artist. The first work collected by the BAO Foundation was Toy Series (1968) — a work from the same year she won an award at the “Salon des Femmes Peintres” in Paris, a series that established her position in the European art scene. We felt this work had a special mix of Eastern and Western styles. Since then, we have collected more works from her across different periods whenever masterpieces appeared on the market.

As we enter her world, we gradually discover that behind her simple purity and gentle vigour lies an avant-garde spirit, independent of any trend. Her self-assuredness makes her an exception among Asian women artists, both in the past and today.

For this reason, we present her as a contemporary artist. We’ve titled the exhibition Objects of Play as a tribute to the most admirable concept in her artistic philosophy: an in-depth exploration of spiritual force and everyday life. We view this philosophy as not only Eastern but also global and eternal — something that feels especially urgent to share with an international audience today.

Private Collection

Despite her international career, Hoo Mojong remains less well-known than male émigré artists such as Zao Wou-Ki. Why do you think her contributions have been overlooked, and what does this retrospective seek to redress?

Valerie Wang: Owing to her geographical distance and reticent nature, this outstanding Chinese female artist was almost unknown in her own country—even within art circles—until she returned to Shanghai.

Firstly, through this tribute to her legacy, we aim to examine the centrality of Asian women in rethinking art history and opening up new perspectives on modernism as an interconnected, multi-dimensional phenomenon. Likewise, we cast a candid and confident new light on the artistic value of this underrated master.

Secondly, and more importantly, we wish to reaffirm the eternal power and value of art in an ever-changing world.

Hoo poured her whole life into her art. She was a thoroughly genuine person, with strong features, powerful hands, and a steadfast and generous nature. Throughout her career, she instinctively avoided passing trends, popular tastes, fame, and politics. She remained true to the essence of life, capturing with her brush and burin a beauty that transcends time and space, cultural context, and political turmoil.

This exhibition is curated to present Hoo as a pioneer who charted a solitary path through the tumultuous twentieth century and across one hundred years of art history—and to reconsider, with a century’s hindsight, the position of Asian women in international modernism.

You’ve described Hoo as transcending the traditional East–West binary within modernist discourse. Could you elaborate on what makes her work resistant to categorisation—and why that matters today?

Valerie Wang: Today, a century after her birth, the world seems louder and more garish. Amid the head-spinning changes in technology, business, geopolitics, and the media, distraction and anxiety have become universal afflictions. Hoo Mojong, holding herself aloof from history, left a lasting, extraordinary legacy that remains strikingly contemporary.

Precisely because of this contemporary quality, our exhibition does not place Hoo solely against the backdrop of modern history: viewing her only as a modernist is too limited.

As we enter her world, we gradually discover that behind her simple purity and gentle vigour lies an avant-garde spirit, independent of any trend. Her self-assuredness makes her an exception among Asian women artists, both in the past and today. However, as a solitary figure, her extremely introverted personality and unsociable lifestyle increased the difficulty of categorising her within art history, with limited archival material and research resources available.

Courtesy of Bao Foundation and Asia Society Hong Kong Center.

The retrospective opened during Hong Kong’s “Super March” and Art Basel. How do you see institutional exhibitions engaging with the energy of global art fairs, without compromising curatorial depth?

Valerie Wang: I believe institutional exhibitions should always go deeper—grounded, visionary, and capable of inspiring a recalibration of art history. This is especially important when they coincide with global art fairs, where audiences are often overwhelmed by a flood of artworks, shown in a hurried and chaotic manner.

This exhibition of Hoo’s work could be a quiet earthquake. The more chaotic the art fair, the louder Hoo’s silence resonates. The question is: how do we ensure that audiences don’t merely see her work, but truly feel the unity it embodies?

Institutional exhibitions must serve as anchors of depth, historical re-evaluation, and cultural equity—reasserting the true value of art, rather than riding the waves of passing trends.

This year, during Hong Kong Art Week—a city where East meets West—we believe it’s not only important to present renowned figures like Picasso to local audiences, but even more crucial to spotlight Asian artists who have been long overlooked on the global stage. That is precisely what we are doing with Asia Society this season, through Hoo’s retrospective exhibition.

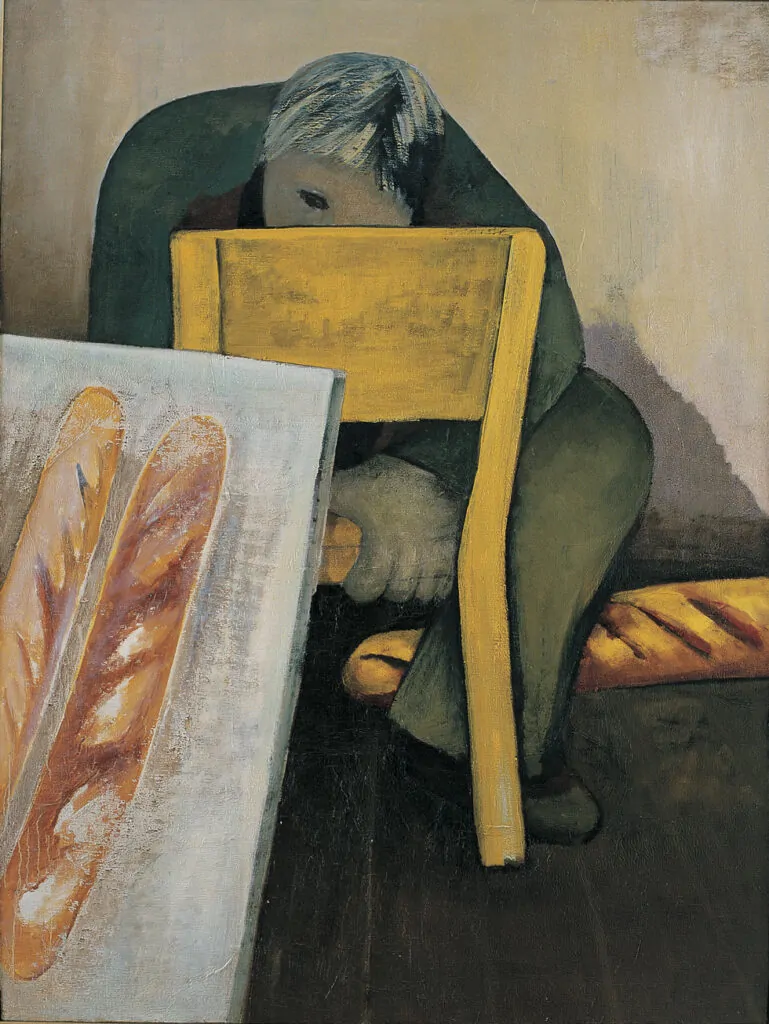

Oil on canvas,

146×114 cm

Private Collection

You’ve worked across journalism, auction houses, galleries and museums. How have these diverse roles shaped the way you approach exhibition-making and legacy-building for artists?

Valerie Wang: Yes, definitely. Every stage of my career has been important in helping to shape the way I approach exhibition-making and legacy-building for artists.

- Journalism: storytelling, sensitivity towards unique figures, and uncovering overlooked histories.

- Auction houses: perspectives and insights into the secondary market, which is extremely fast-changing in terms of artist rankings, trends, and prices. Yes—like surfing.

- Museums: inspiring audiences and pioneering within the professional arena, bearing the responsibility to rediscover and reshape history, present potential value, and offer a different angle and vision beyond the art market.

Museum exhibitions and activities are like building and nurturing the eco-environment of the sea: discovering new specimens, protecting and raising awareness for those species that need attention. Meanwhile, auctions are like surfing big waves and fishing from a boat—taking what the weather offers.

However, compared to career experience and background, my graduate study at Peking University Philosophy department is very crucial. It’s the unseen architecture of my curatorial and collecting practice.

Was there a particular work or archival discovery during your research that altered your understanding of Hoo Mojong—or moved you on a personal level?

Valerie Wang: Hoo impressed me most with her extensive portfolio of copperplate print works.

In 1970, because of the success Hoo had won in Europe, the French government arranged a professional studio for her in the 14th arrondissement, which allowed her to produce larger-scale works. Around the same time, to make a better living, she started to study copperplate printing, opening up an entirely new field in her art.

Like other modern masters in Paris, she viewed her early printmaking practice as a market supplement to her art and business. Even so, Asian women in printmaking at that time were few and far between. Hoo Mojong’s printmaking studio once belonged to Zao Wou-ki, and stood right next-door to Alberto Giacometti’s studio.

Hoo plunged into this new field with her characteristic persistence and eventually became a talented printmaker who produced outstanding work. Indeed, her prints took part in exhibitions in different countries in Europe and sold well. Printmaking naturally became an indispensable part of her career, and an important component of her decades-long exploration of a formal language. It is also a testimony to her growing artistic maturity and independence in Paris.

Yet time spares nothing, and of that once considerable body of work, only some 90 prints remain, scattered after half a century. Our exhibition is lucky to be able to show 20 copperplate prints of different subjects and styles from the 1960s to the 1980s. What’s more, nine rare original copperplate masters of early prints are also on display, allowing the public to see with their own eyes the artist’s delicate touch from her printmaking period—doubtless an invaluable legacy.

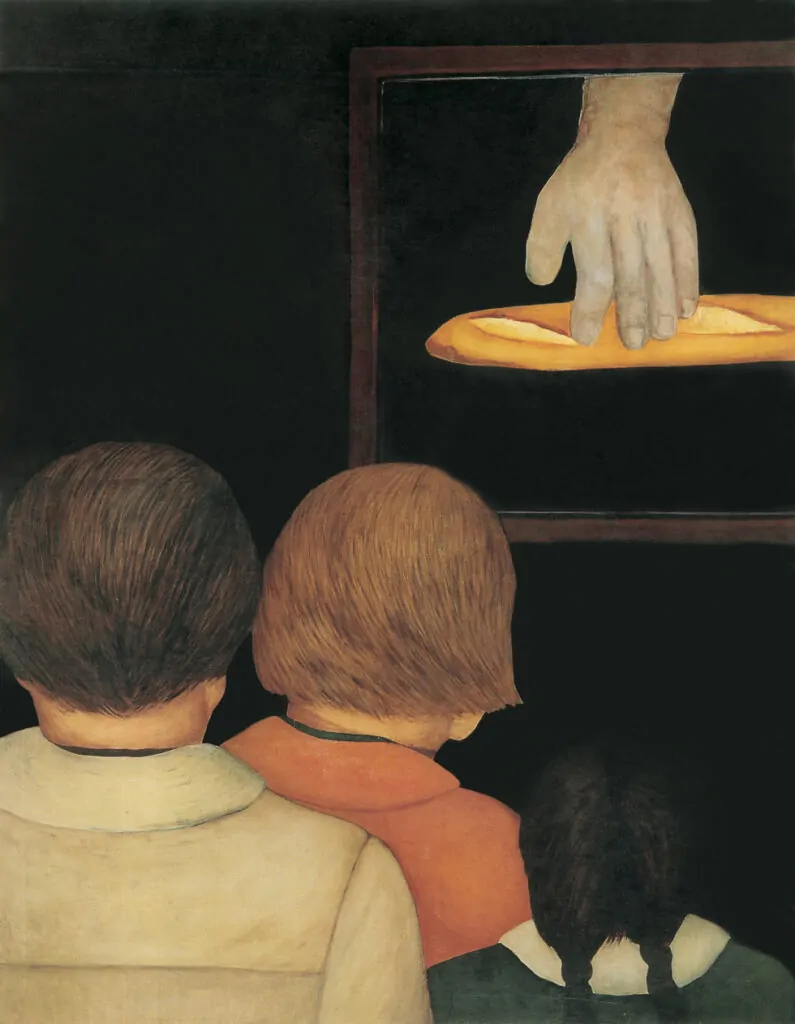

Hoo’s prints retain her familiar simple, natural qualities, and her subject matter often echoes that of her paintings: fruit, bread, utensils, and ordinary people. Unlike the thick intensity of her oils, here we can often see fine, delicate details and unexpected colour combinations. Her prints likewise show more playful, amusing animal subject matter, such as a fat, lazy cat, an owl with gleaming eyes, or a stout tortoise.

These have the understated charm of the familiar. Poignant moments often appear on the paper, such as a daughter cuddling up with her father, a mother playing with her son, workers at rest, or an outing to the countryside. With a sharp tool, she portrays stirring scenes that transcend the turbulence of the day and perennially warm the heart.

You’ve led both commercial and non-profit art institutions. How do these diaerent models influence the way underrepresented stories—especially those of women and diasporic artists— are told and valued?

Valerie Wang: A Distinct Phenomenon in Asia’s Art Ecosystem

A unique characteristic of Asia’s art landscape is the disproportionate influence of commercial institutions over non-profit entities. This stems from several structural factors:

- Comparative Youth of the Ecosystem

Unlike the West’s established art infrastructure, Asia’s ecosystem developed later, resulting in auction houses advancing faster than museum-building. Consequently, collectors have traditionally relied more heavily on auction results when assessing artistic value. - The Shifting Paradigm

This dynamic is now evolving. The growing establishment of both private and public museums—supported by increasing governmental and private funding—is gradually rebalancing the ecosystem’s valuation mechanisms.

The greatest challenge—and most exhilarating odyssey—in leading an institution lies in carving pathways for underrepresented narratives with purposeful vision.

At ZHI ART MUSEUM, our eight-year journey as a non-profit has been a sustained pursuit of this mission: redefining Eastern aesthetics through global discourse. This intellectual commitment demands more than trend resistance—it requires scholarly rigour, strategic patience, and active cultural mediation. Through deep research, we pioneer academic frameworks that anticipate rather than follow, influencing both critical discourse and market evolution.

While the market undoubtedly serves as an important barometer, it should never be regarded as the definitive measure of artistic value. In commercial art institutions, success demands agility, adaptability, and the courage to innovate—not merely following trends, but actively shaping them to elevate artistic works.

These two institutional models have honed distinct competencies within me—they function like dual wings, equally indispensable in empowering artists to soar. I’ve been fortunate to engage deeply with both, participating in the full cycle of establishing and redefining artistic value—particularly for women and diasporic creators. As both the founder of the museum and a woman myself, this mission resonates with profound personal passion.

Foundation and Asia Society Hong Kong Center.

The Bao Foundation formally launches with this exhibition. What is your vision for the Foundation, and how do you hope it will help reshape the discourse around Asian art globally?

Valerie Wang:

Reconstructing the Eastern Imaginary

The Bao Foundation is a creative platform dedicated to re-examining and enhancing the appreciation of Eastern art, culture, and philosophy within a global framework. Rooted in the sustained exploration and practice of Eastern thought, the foundation was established amid significant global historical shifts.

From its base in the Hong Kong SAR, with branches extending across China and Asia, the foundation collaborates with artists, curators, researchers, and scholars who share its vision—fostering a reimagining of the “East” through interdisciplinary projects.

Through active participation in the co-construction of global artistic and cultural discourse, the foundation seeks to build bridges between cultures, promote deeper transcultural resonance, and drive global collaboration and understanding.

Courtesy of Bao Foundation and Asia Society Hong Kong Center.

Through initiatives like Open East: Asia Museum Forum, you advocate for a re-narration of Asian art. What kinds of institutional or curatorial changes do you believe are still necessary to achieve this?

Valerie Wang:

Open East: Asia Museum Forum, initiated by ZHI ART MUSEUM, is both a strong will and a concrete action—aimed at connecting art institutions specialising in Asian art across the globe to promote Eastern art, aesthetics, and philosophy.

The first Forum, held five years ago, was just the beginning of this journey. We invited Asia Society to participate in that inaugural edition, and Hoo’s exhibition now marks the second significant collaboration between our two institutions. With The Hoo Retrospective, we aim to present a case study in institutional leadership.

Through this regular annual event, we hope to foster more collaboration in academic research and publication, case studies, curating, and the global touring of exhibitions.

Our purpose is twofold: to help the world better understand Eastern civilisation and, more importantly, to awaken shared human values and wisdom through that understanding. Ultimately, we come to realise that there is no fundamental divide between East and West—universal wisdom transcends such boundaries. Art serves as our ladder to this enlightenment.

For emerging curators working across cultures and disciplines, what advice would you oaer

on navigating art history, advocacy, and institutional structures while maintaining a critical

voice?

Valerie Wang:

- Observe trends, but never follow blindly

- Dive deep into human hearts, and fundamental truths to create new movements.

- Truth and goodness inevitably blossom into beauty—eternal and self-evident. All constructs of artifice are but fleeting shadows in time.

Learn more

©2025 Valerie Wang