Robert Colescott: Women

November 15, 2022 – January 14, 2023

Venus Over Manhattan

55 Great Jones Street

New York, NY 10012

Venus Over Manhattan is pleased to present Robert Colescott: Women, an exhibition organized to trace the development of the artist’s depictions of female subjects over the course of his sixty-year career. Serving as a coda to the recent, critically-lauded traveling museum retrospective Art and Race Matters: The Career of Robert Colescott, this presentation charts the evolution of Colescott’s ambitious practice through some thirty works produced between 1955 and 1996. Organized in close collaboration with The Robert H. Colescott Separate Property Trust, Venus Over Manhattan’s exhibition is the first to trace the development of Colescott’s representations of women through major works from key moments in his career.

Robert Colescott: Women will be on view at Venus Over Manhattan’s downtown location at 55 Great Jones Street from November 15, 2022 through January 14, 2023.

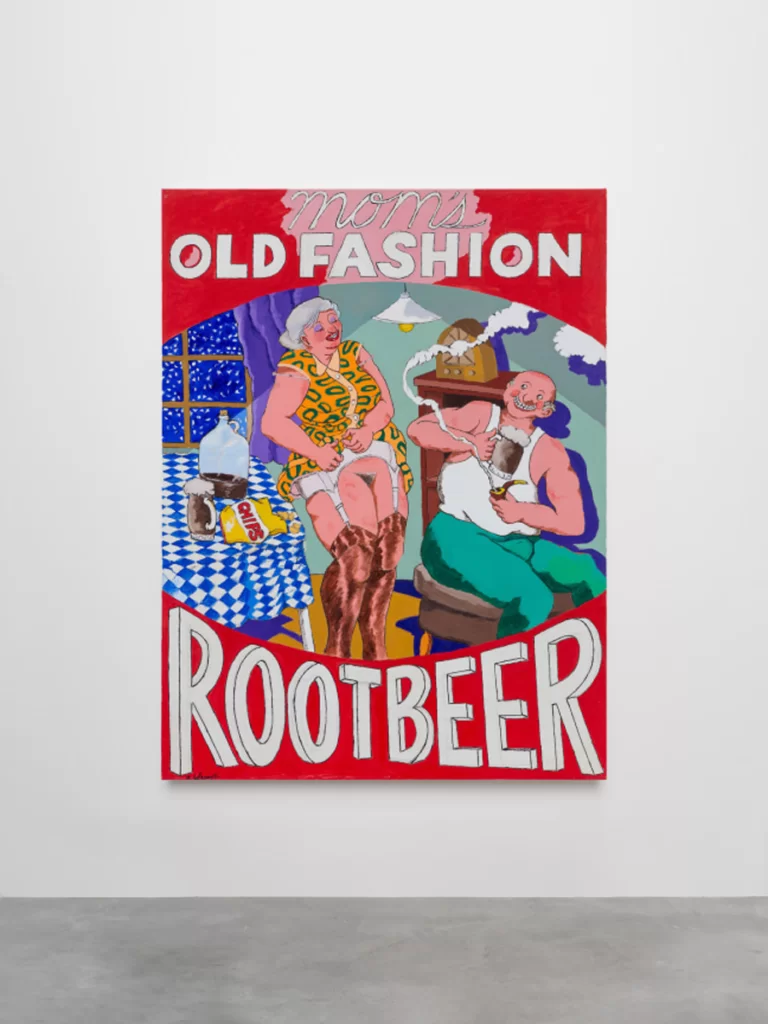

Nearly fifteen years after his death, Robert Colescott remains best known for audacious, satirical, and racially charged paintings like Eat Dem Taters (1974), George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware: Page from an American History Textbook (1975), and Natural Rhythm: Thank You Jan Van Eyck (1976), which recast familiar Euro-centric compositions to interject “[B]lack people into art history.”

Populated by a cast of racist and misogynist caricatures, these blunt appropriations enlist the artist’s signature blend of confrontational humor, startling subject matter, and vivid color to undermine widely held cultural assumptions about history, race, and gender. These bawdy, troublesome works date from the middle of Colescott’s career—he turned fifty the year he painted George Washington Carver—but their concerns, and the painful stereotypes they employed to address them, were hardly new to his practice.

A light-skinned Black man raised to pass for white (and whose brother identified as white), Colescott made work that often exploited racist and sexist imagery to address his “perception of himself as a Black male and an artist in America.”

Tying his private concerns to public issues, Colescott deployed this imagery with various intensity throughout his career, but consistent across his work is a frank engagement with the female figure, which he used to explore his complex—and sometimes objectionable—relationship to women.

Writing about his career in 1987, curator Lowery Stokes Sims noted that “Colescott’s depictions of women have pro- vided some of his most interesting and relentless imagery,” and until the end of his career Colescott would continue to cast women in difficult roles, considering the layered effects of race, power, and stereotypes on their position in both society and his own life.

Private Collection. © The Robert H. Colescott Separate Property Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of The Trust and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo, and Venus Over Manhattan, New York. Photo:

Colescott developed a set of consistent visual strategies that he used to explore increasingly complex topics around gender, many of which are evident in his early work. There Are Two of Us (1955), the earliest painting in the exhibition, employs a strategic doubling to render a pair of nude figures, and renders his subjects racially ambiguous with expressionist brushwork fashionable of the era. In Cloud Watch (1963), a nude man and woman lounge in a sparsely appointed interior, from which the woman observes a bucolic landscape through large windows that bisect the composition.

The window allows Colescott to juxtapose interior and exterior space, and he would continue to exploit the visual possibilities of what he called the “magic window” to great effect in his later work. Discussing this strategy, Colescott described the window as “a kind of barrier” that allowed for “looking at two planes in existence. The outside was not just looking through a window, but the outside seemed to be a very different kind of place, and maybe a different time.” In his depictions of women, Colescott would frequently juxtapose discontinuous scenes to animate tensions about race and gender and establish visual distinctions between art and reality.

©2022 Robert Colescott, Venus Over Manhattan