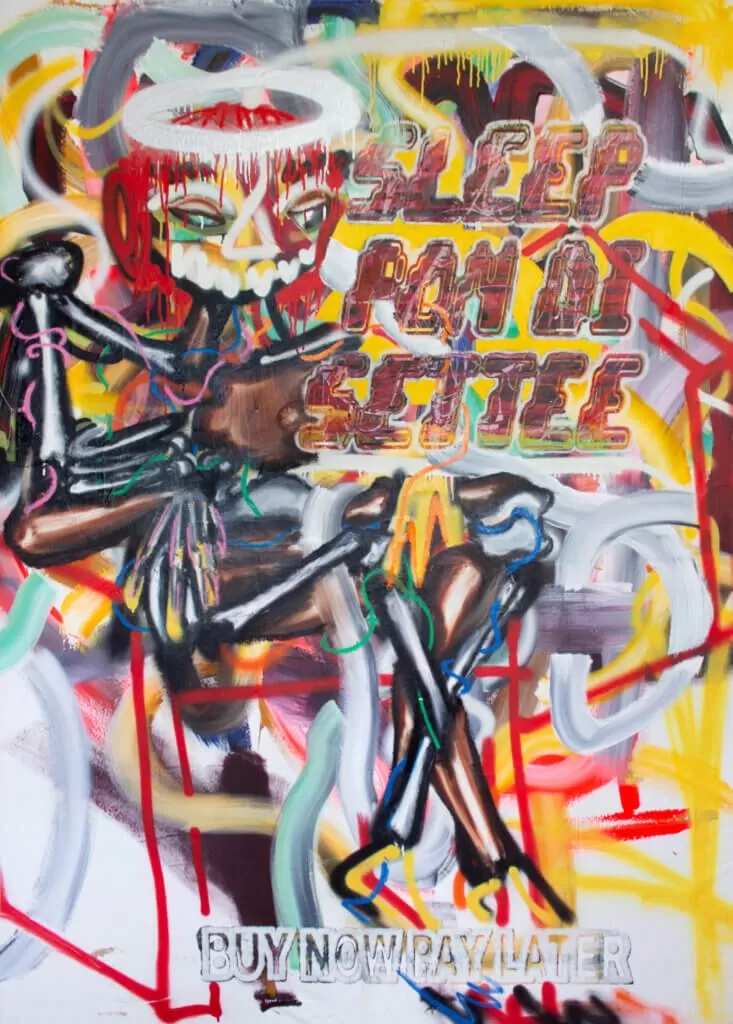

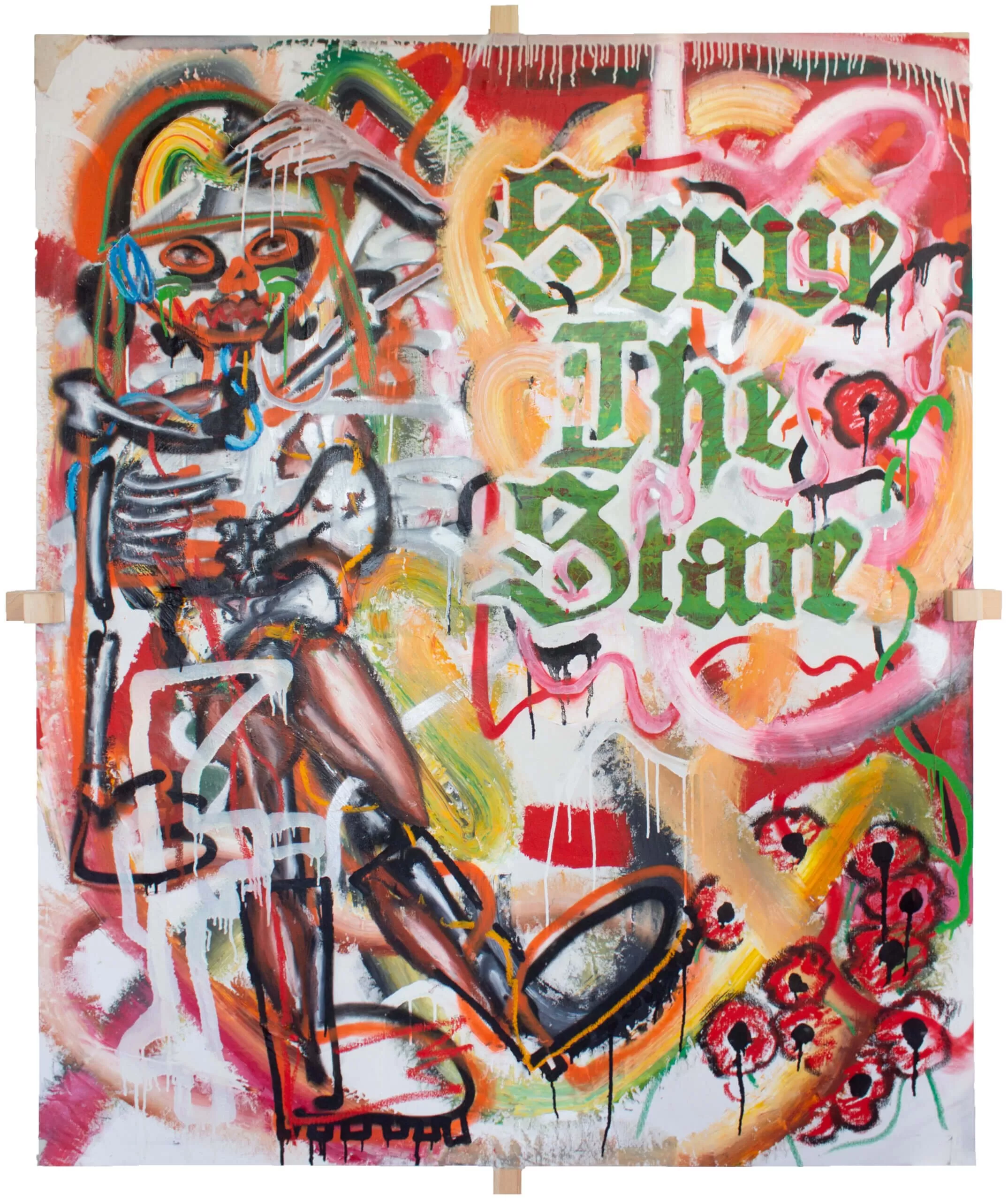

Emerging artist Niall Ashley is a self-taught painter from Bristol; his work explores authority, classism, racial identity and the Black experience manifested in vivid paintings.

Inspired by aristocracy’s red tape, he considers painting as his vessel to communicate society’s unheard voices. He reveals his experiences in a visual cacophony of colour fused upon canvas, incised with expressive figures defined by meaningful typography.

I identify as Black and Non-Binary, with my work sampling heavy from this experience, as well as the impact of bureaucracy and class

Niall Ashley

Naill has succeeded in amalgamating his presence amidst Graffiti and Neo-expressionism with a little Basquiat-Esque tactility. He is an imaginative talent who will continue to grow as he explores his creative palette, indeed an emerging artist to keep a watchful eye on.

Q: For those who don’t know you, can you please introduce yourself

A: Yo, I’m Niall. I’m an artist from Bristol making large-scale expressive paintings, combining aspects of typography and figurative painting. I identify as Black and Non-Binary, with my work sampling heavy from this experience and the impact of bureaucracy and class.

Q: What is your inspiration, and why do you do what you do?

A: I would say my earliest inspirations were seeing Banksy pieces thrown up all around Bristol. He was an artist who had a political tangent to his work whilst simultaneously talking to the average person who’s just making ends meet. Painting always seemed like an art form reserved for the well-educated upper class. When I found Basquiat, an artist who managed to pave his way identifying as Black and being previously homeless, it struck a chord in me that someone from a similar background did it too.

These two artists solidified a crazy faith in me that art is a means to change the visual landscape and platform voices of the marginalised. I feel part of a forgotten fraction of the population from low-income families, made to feel like a pseudo-citizen of their own home country. So, this is why I paint, to show that our experiences and stories have a place in this veneered and polished world.

Q: Can you tell us about your creative process?

A: Typically, I imagine the canvas as a sketchbook I used to take on my tube journeys. I sketch a figure instinctively using spray paint or oil stick, as it’s the two materials that match closest to a forever flowing pen. Sometimes I do the reverse, starting with envisioning the background as a 3-Dimensional plane where the strokes overlap weave to expose a hidden figure. I’ve borrowed this from Gerrit Noordzjj’s typography approach of seeing letters as 3-Dimensional carvings of space, rather than the convention of looking at letters as shapes.

The typography in my work is an aspect of my creative process. I delve into accuracy and measurement, taking phrases that are colloquial to my childhood or symbolising a current political tension voiced on social media. As the type we encounter in our day-to-day life is usually projected from screens and digitally printed fonts, I aim for my lettering to emulate that cold feeling it expresses to us. This is quite labour intensive, but I think the process of designing typography on a computer and transferring it to a painting through screenprint or painting by hand is worth the monotonous effect.

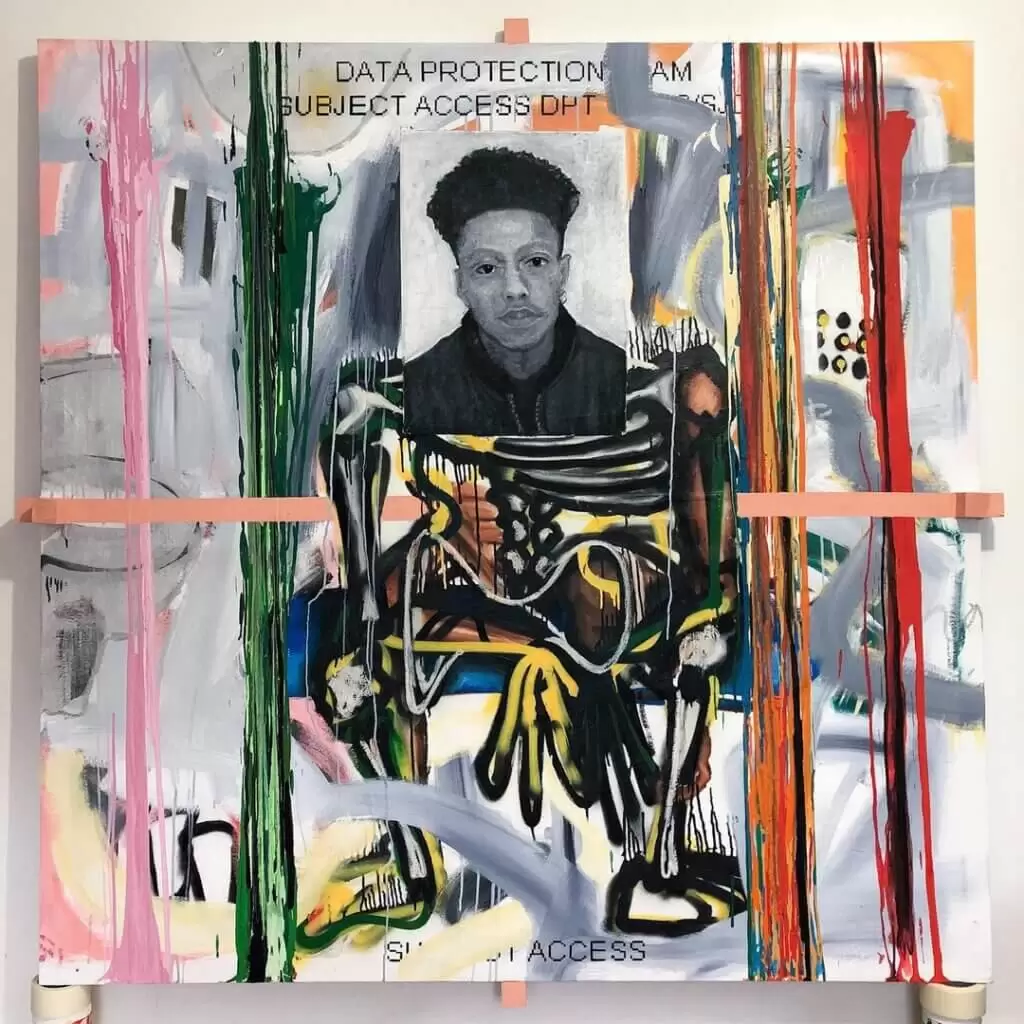

acrylic, oil stick and screen print on canvas mounted on wooden supports

161.7 x 186.1 cm

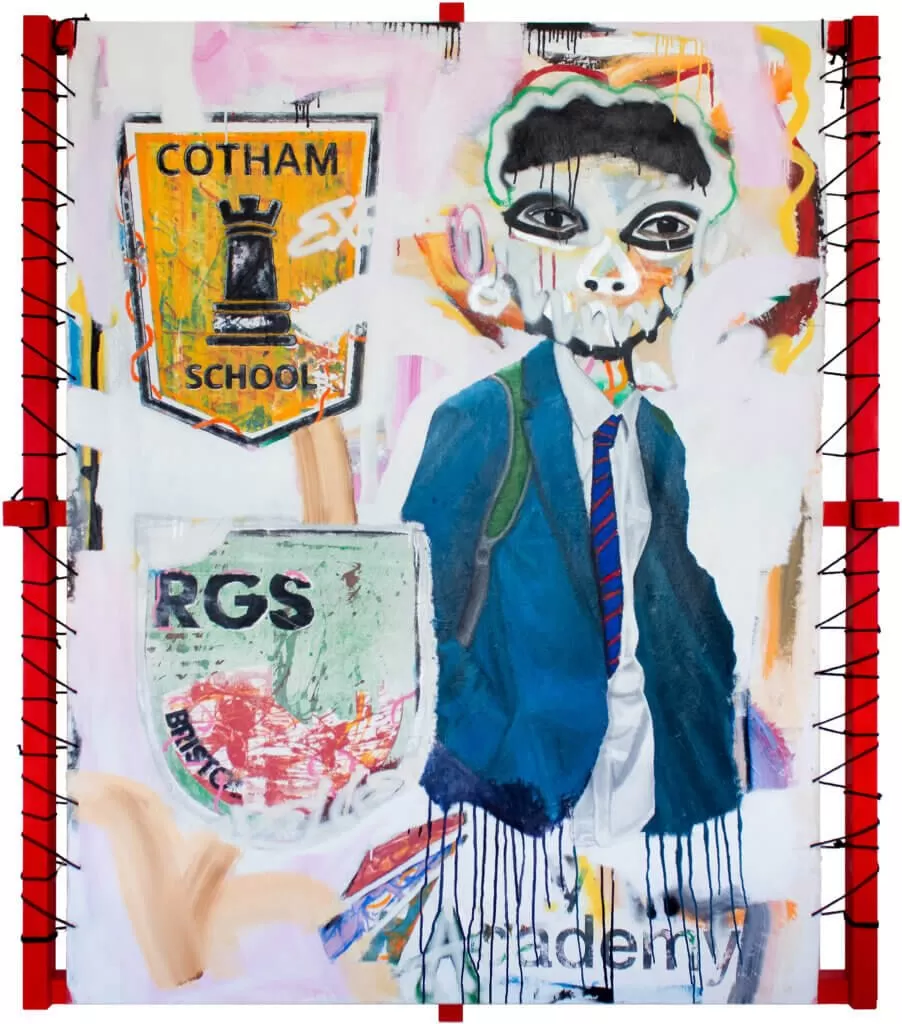

Q: What is the reason behind your fusion of bureaucracy, class and racial identity in your work?

A: I realised that bureaucracy plays a major part in the life of the lower class, where my younger life existed. Our livelihood is dictated by eligibility to benefit systems, council housing, free school meals, scholarships, bursaries etc. We almost become numb to the amasses of forms, letters and bills which take grasp of the normality in our lives.

All the complexities compressed into black and white. I communicate this cold feeling through typography, trying to fight the colourful and expressive aspects of the people I paint. I feel that blackness is depicted as a monotonous noir. When realistically, we see black people of so many different hues. I don’t want the black figures to be a fetishization of who we are but rather a transparent representation in my painting.

Q: What was the first piece of Art you made that cemented your path as an artist?

A: I started painting about two years ago, so I’ve had to catch up a little. But the first proper pieces which I felt opened up a conversation was the work I made in response to the xenophobia and anti-Asian sentiment after COVID-19 broke out. It was the first time I felt that I used my voice through my painting. These works are named ‘Daegu’, ‘Veneto’ and ‘Wuhan’. All locations where people suffered at the hands of the virus yet received brash amounts of racism from the media and the western world.

I tried to incorporate a bilingual approach of incorporating messages in response to hate-crimes; for example in Veneto I mirrored the phrase ‘nobody defended me’ in Italian, English and Chinese, using the languages symbolically and communicatively. It was eye-opening hearing the stories of friends who identify as Asian and hearing their experiences and concerns amid the outbreak. This is still an important topic now. As hate-crimes are rising rapidly, I think artists need to do more work that touches these topics, being an ally or representing their respective communities. As a black artist, I can recognise the feeling of being unheard and perpetrators of these crimes not being held to justice.

Q: What is your favourite piece?

A: My favourite piece of mine has to be ‘Wolf in Child’s Clothing’, a piece sampling one of my child police custody mugshots at 16. It felt like work that had been in the making since I was a teenager. I felt quite violated from all the run-ins with police I had, typically stemming from neighbours calling 999 whenever they heard my family argue. I had been arrested more than 20+ times because police would barge through our door and see me as some violent aggressor. It was like as soon as they saw it was a black family causing inconvenience for our over-sensitive and, quite frankly, racist neighbours, then they had to take one of us in custody. And because to the world, I was seen as an adultified black boy, and I was the one they picked. My brother was also already known to the police, and I remember them telling me at numerous points that they were going to institutionalise me just like they were attempting to with him.

Q: What do you think about the current state of the art world?

A: The artworld is already seeing a significant shift, I believe. The entrance of NFTs (Non-Fungible Tokens) and the crypto blockchain in selling and collecting art are changing what can be owned. I remember Marina Abramovic talking about how performance art couldn’t be sold.

acrylic, oil stick, spray paint and screen print on canvas mounted

on wooden supports

151.8 x 182.3 cm

Maybe you could take a video of a performance or photographs as excerpts from the performance. But the performance was ultimately deduced in the act of the collector owning a piece of it. With the format of NFTs, ownership and authenticity of a digital file (JPG, MP4, WAV, PDF) can be proven via the blockchain I, for one, have done performance works that extend from my paintings, and now with NFT, I can allow people to collect them. So as saturated as the art world has felt, this new technology is starting to add a breath of fresh air and room for all types of contemporary artists. The environmental impact of NFTs does need some attention, and the jump from Ethereum’s POW (Proof of Work) to a POS (Proof of Stake) system should reduce the energy needed for this technology.

Q: What role does the artist have in society?

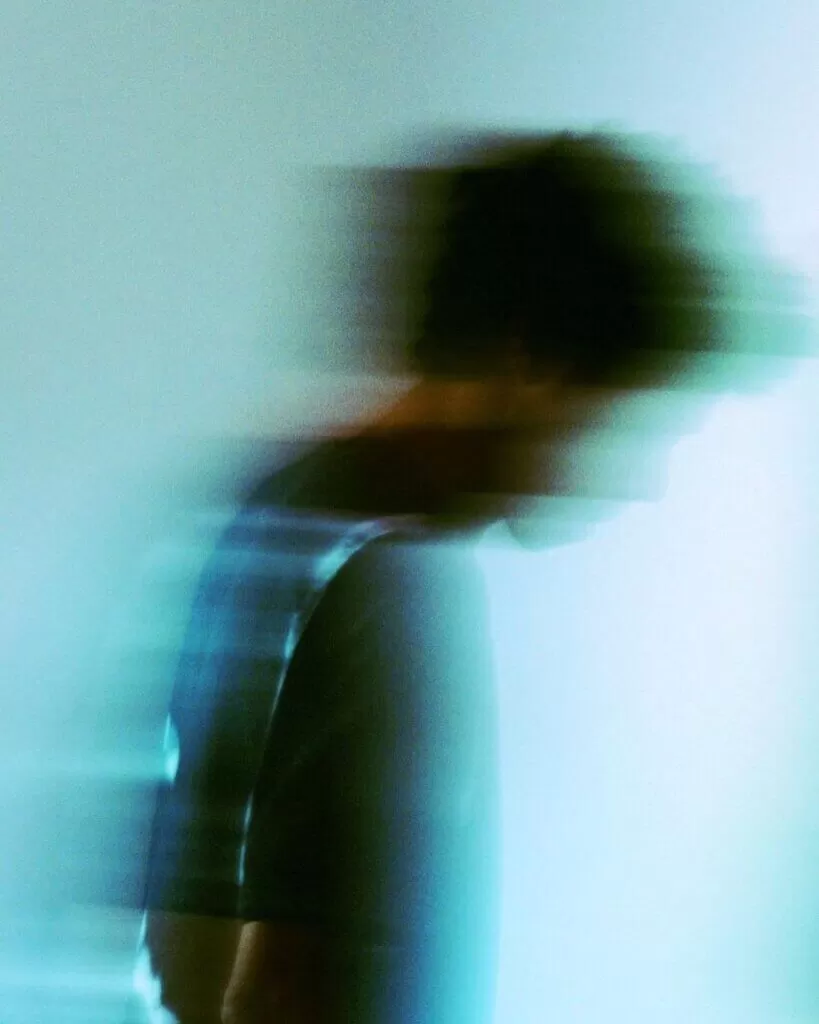

A: The artist is someone who fights for what they believe in. They expose all facets of their life out to the open. And in a society where many of us feel afraid of people discovering our identities, what we love, what we hate, the embarrassing things we’ve gone through which don’t make our social media highlight reel, we need artists.

Q: What impact do you think Instagram has had on Art?

A: I think the most exciting thing about Instagram is the format. You’re squishing your art into a compressed thumbnail on your profile. Yes, Instagram allows you upload at many different ratios, but it’s a square, very low detailed image on your profile. So, say someone finds your page; the first thing they are seeing is those cropped squares. I think inherently; it affects how we make art later published on Instagram because we have to factor in what our painting will look like on a screen and in a small square. There are a couple of artists’ works who I’ve loved on Instagram, but when I’ve gone to their shows, the work feels completely different in person. And I almost feel tricked in a way, but I don’t think it because the work isn’t the same; it’s just I was accustomed to seeing it presented in a particular light.

Q: Which artists have caught your attention in the last five years?

A: I went to Meleko Mokgosi’s exhibition at Gagosian last year; I was in complete awe of how well fleets of abstraction came together cohesively with realism. In a weird way, the paintings felt hyper-real, maybe due to the underlying cultures shared between Black experience. Jamian Juliano-Villani is another artist who’s making work that I’ve never seen before by congregating imagery whose context don’t traditionally overlap. I love Moyosore Briggs self-portraits; which act like a portal into their identity, psyche and experience. I see each portrait as a painting, showing a different side of their complexity.

Q: What’s next for you as an artist?

A: I would love to land my first solo exhibition and begin to start experimenting with the possibilities of machine learning. I’ve been intrigued with using it as a tool as it feels like a real threat to painting as we know it. I also want to keep exploring the medium of NFT, I think it’s an inspiring space.

Q: Lastly, what does Art mean to you?

A: Art, to me, is the act of opening dialogue. Its ability to spark debate and deep emotions within people is unparalleled. It’s unfiltered and non-conforming, which makes it such a cathartic obsession for me. I have been conditioned to bottle up my feelings over the years, and with art, I can say how I truly feel.

http://twitter.com/niallashley_

©2021 Niall Ashley