Brooklyn-based artist Natalie Wadlington‘s work is a captivating exploration of the relationships between humans and animals. Brought to life through her practice, which encompasses paintings, drawings, and sculptures, she deeply immerses viewers in her craft of storytelling and figuration.

Wadlington delves deeply into the complexities of these interactions, using them as metaphors for broader themes like love, conflict, and misunderstanding. These themes are especially pronounced in our interactions with animals, reflecting the intricate dance of mutual understanding we often struggle to achieve with our human counterparts. Wadlington’s pieces advocate for a mutualistic approach, underscoring the essential interdependence that sustains humans and animals on our shared planet.

All photos by Paige Beitler.

Courtesy of the artist and Library Street Collective

I find painting to be a great space for exploring tensions, because different elements must all coexist on the canvas

Natalie Wadlington

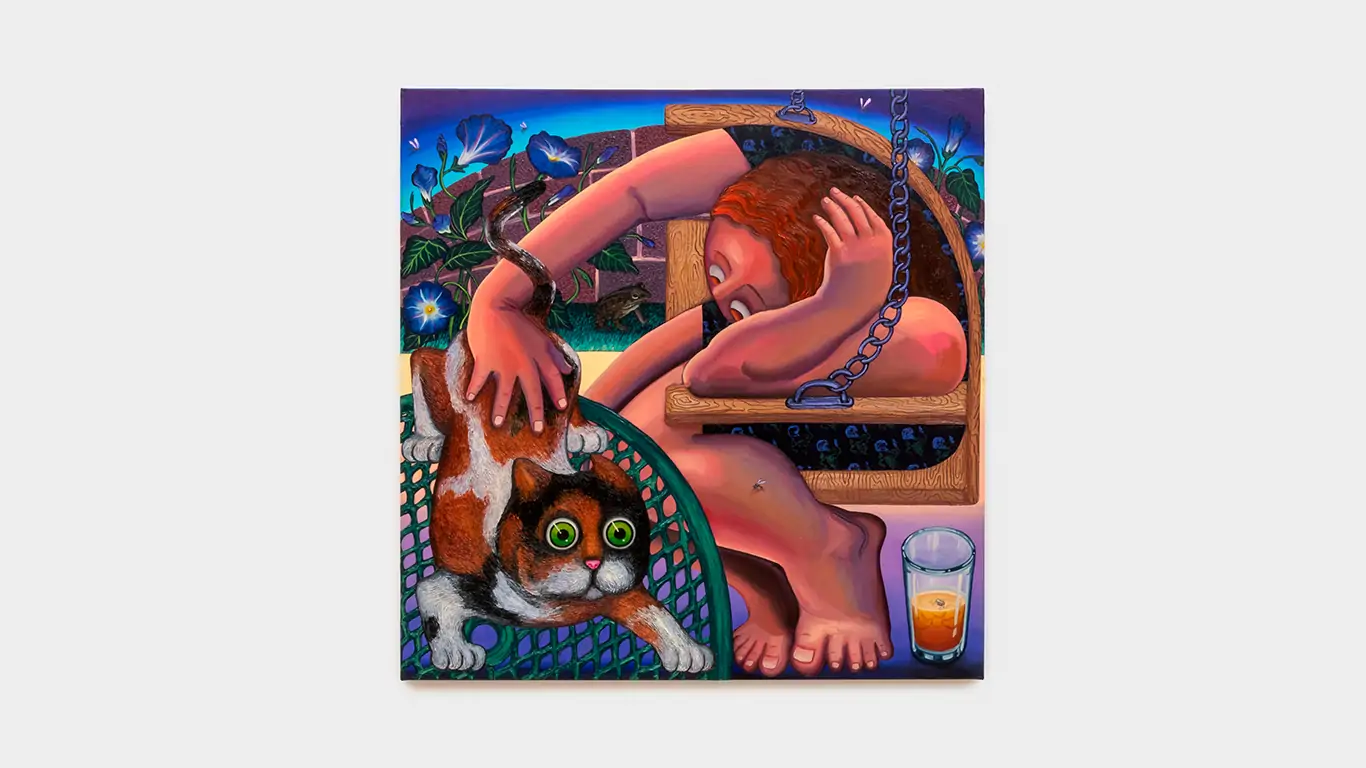

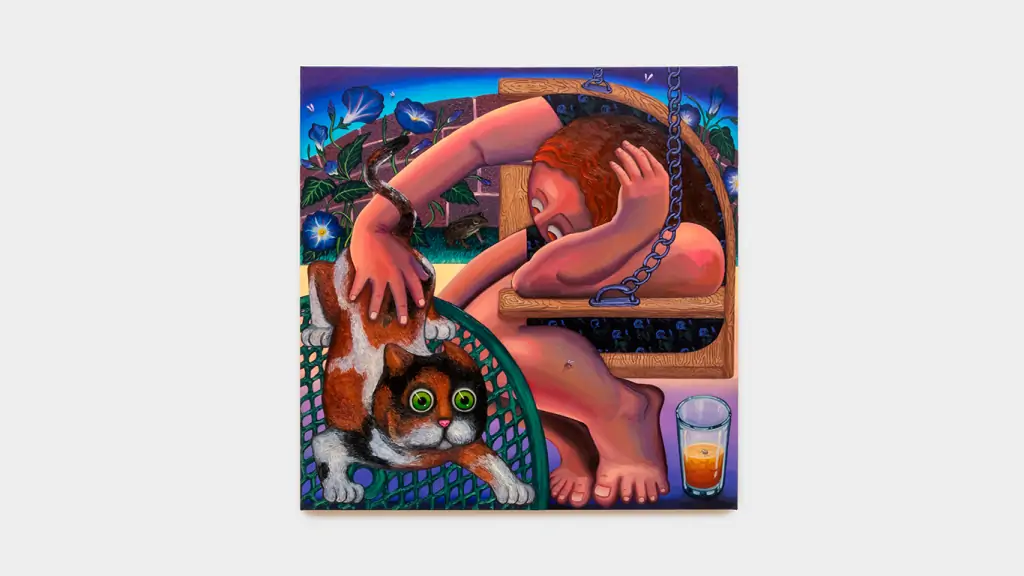

The themes that are vividly portrayed in her piece “Swing Bench” stands out to me. In “Swing Bench,” Wadlington’s use of light and shadow casts a warm, tangible glow over the scene. The palette is awash with the luminescent hues of twilight, the blues and purples of the flora, emitting a dreamlike quality central to the narrative.

At first glance, you are greeted with an intimate moment of domestic repose. The central figure, relaxed in the embrace of a swing, displays a fluidity that defies conventional portrayal. The presence of the glass, seemingly containing iced tea with an insect floating in it, innocuously placed, is rife with latent symbolisms, suggesting the heat of a summer’s day. Yet, the insect hovering above and the frog witnessing the interactions speak to the transience moments of nature and daily comforts.

However, it is the interaction with the feline companion that truly encapsulates Wadlington’s rendition of anthropomorphism. The figure’s hand, draped over the cat in a possessive yet gentle manner, raises questions about mutual understanding and the projection of human emotions onto animals. With its wide, almost human-like eyes, the cat’s expression is one of surprise, curiosity, or perhaps a tinge of anxiety, mirroring our own reactions to personal intrusions. Wadlington’s figure reaches for connection and understanding, but does the cat want to be touched? Is this a mutual exchange or merely a projection of human sentiment?

Wadlington’s work is a conversation between humans, the tame, and the wild animal—a delicate dance of narratives spun from human-centric introspections. It makes her canvases more than mere visual delights; they become portals into the ebb and flow of mutual reliance and existential entwinement, echoing the deep-rooted symbiosis of shared existence. Unscripted conversations with Mother Nature’s witnesses become poignant observations of life.

Wadlington is originally from Modesto, California. She received her BFA from California State University, Stanislaus, in 2017 and completed her MFA in painting from Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield, Michigan, in May 2020. Wadlington currently lives and works in Brooklyn. Recently, she exhibited her work at Library Street Collective in an exhibition titled “Pollards“. We had the opportunity to catch up with her and learn more about her art, creative process, and sources of inspiration.

Hi Natalie, please tell us about yourself and how you embarked on your path in the arts. What inspired you to pursue a career as an artist?

Natalie Wadlington: I’ve always drawn since I was a child. I was first encouraged to pursue art by a professor in undergrad, and it all clicked into place for me. I began ravenously reading art history and scouring the university library for art books, and have not looked back sense. I was immediately taken with the history of painting and the contemporary discourses around it, particularly the ground broken by artists like Dana Schutz and Nicole Eisenmann. I want to contribute something to painting conversations and histories.

40 x 40 in

101.6 x 101.6 cm

Your practice revolves around paintings that blend storytelling, figuration, and specific metaphors, creating expansive tales of love, conflict, and misunderstanding, with a special focus on our interactions with both wild and domestic animals. Could you give us deeper insight into your practice, what inspires you, and the importance of these themes in your artwork?

Natalie Wadlington: I find painting to be a great space for exploring tensions, because different elements must all coexist on the canvas. The finite, two dimensional nature of the canvas is quite restrictive, but there is so much scaffolding to build off of that framework. Story telling, emotional expression, psychological slippage, and phenomenological experience can all be explored in paint, and what you choose to put down on the surface is crystallized like amber. Our relationship with animals is complex because it can illuminate not only what is inside us but also give us insight into our limitations as people, and connect us with worlds beyond our strictly human conceptions.

I’m also curious about the artistic influences that have shaped your storytelling and figurative techniques in your paintings. How have your style and thematic focus developed over your career?

Natalie Wadlington: Regarding the flatness of the canvas: it’s important for me conceptually to think of everything on the canvas existing in a simultaneity. The imagery on the canvas can be thought of as hieroglyphic and symbolic, with everything existing for the viewer’s perception. That is why the figures are turned towards the viewer, and the compositions are pieced together through much drafting and reworking. The canvases are also mostly square, because I don’t want to privilege either the figure (portrait) or environment (landscape) orientation. The figure, though central, is flattened and abstracted, surrounded by a space that is comparatively dynamic and “realistically” depicted.

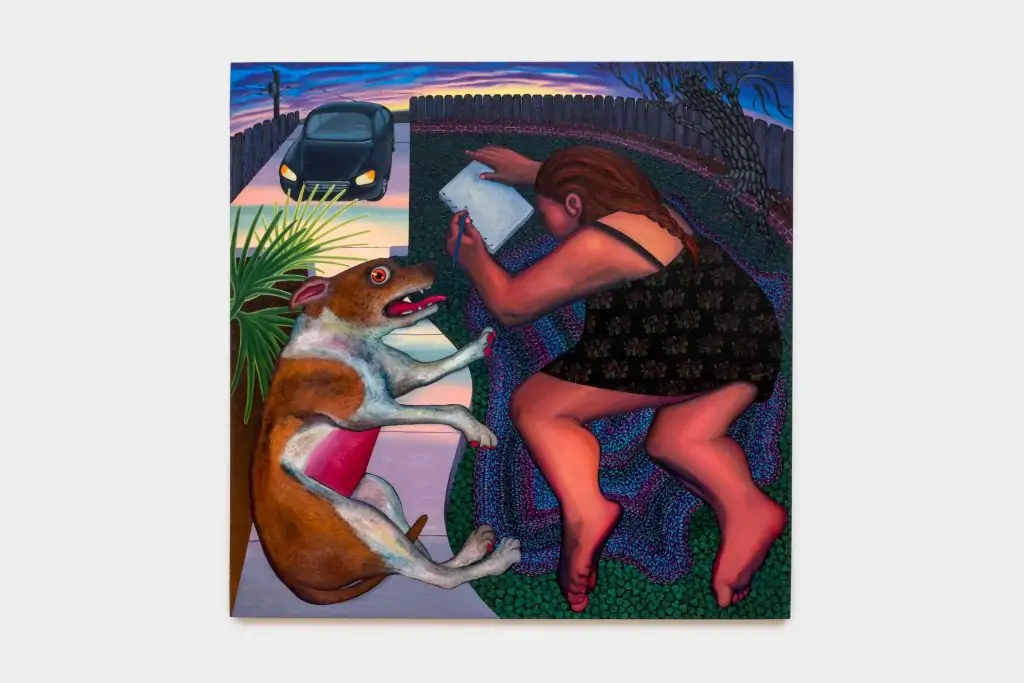

60 x 60 in 152.4 x 152.4 cm

Moreover, your paintings are rich in symbolism and seem to draw upon archetypal stories. Could you explain your process in selecting and cultivating these symbols and how they reinforce themes of love, conflict, and understanding in your work?

Natalie Wadlington: The story telling is informed by personal experiences, but generalized so as to be legible to the viewer. It is less important to me that I tell a specific story, but that the viewer see shared experiences in the work. However, the scene must be drawn from personal experience, as that lends the work a specificity that informs everything about the piece: from the composition, to the colors, the mood, and the figure’s gesture. I channel the feeling I recall from that experience into the making of the piece. Emotional potency is important, because I think paint has the power to hold those feelings and moments.

60 x 60 in

Your technique of merging different painting styles within tightly framed compositions is fascinating. How do you think this approach influences the viewer’s interpretation of the dynamics and relationships between human and animal figures? Does this method amplify the narrative aspect of your artwork?

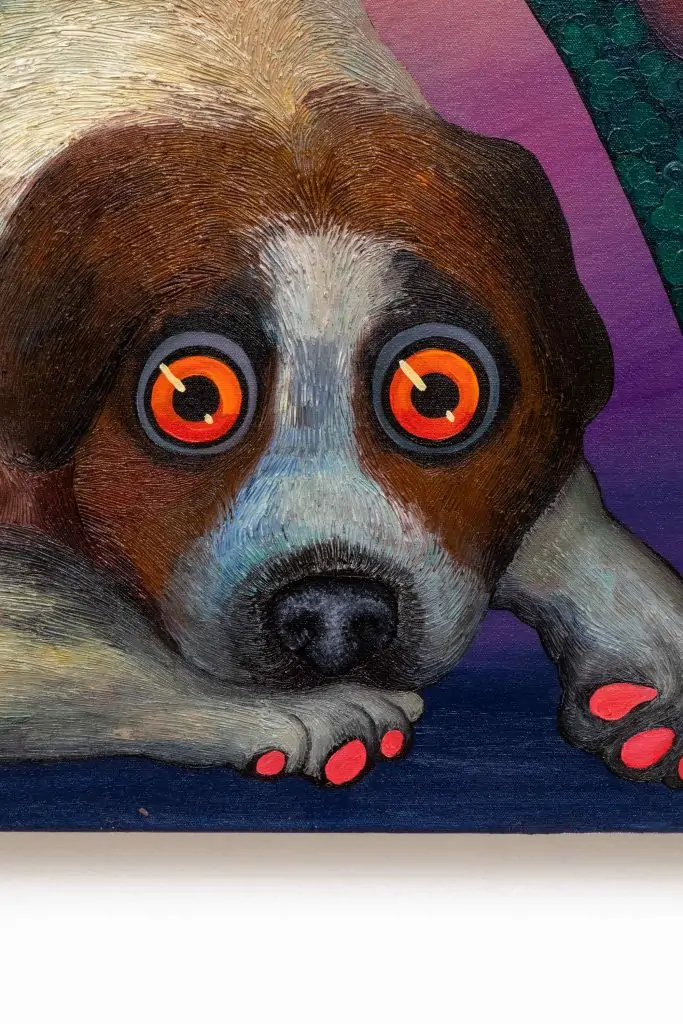

Natalie Wadlington: Yes, the disparate styles of depiction is intentional, as I want the space to seem both lived-in and fractured. I am suspicious of a sense of “atmosphere” in painting, I don’t want the paintings to be windows into a space, but physical things that are present on the surface of canvas: something that exists both in physical space and in the conceptual mind of the viewer. Things are depicted in the paintings either more or less stylized: some things seem like real depictions of an object or animal, others are abstracted and stylized to elicit an emotional tenor about the thing. This is a decision I make intuitively, based on what I think is the appropriate representation of the thing, given its specific narrative import for the painting.

Your recent exhibition at Library Street Collective, titled “Pollards,” features a variety of works, including paintings, drawings, and sculptures. Could you elaborate on this exhibition and the concept behind its title?

Natalie Wadlington: Pollarding is a practice of pruning trees either for agricultural or ornamental value. It keeps them manageable and in a slightly juvenile state. This is beneficial for the tree, as pollarded trees tend to be healthier and live longer. I think much of living is a process of pruning for self care and benefit. Yet artists always have a curious and porous relationship with boundaries, and it is what we are always pushing. The canvas, as I spoke of earlier, is quite a bounded thing, yet so much is possible within it. These tensions are a source of endless fascination for me, and the guiding theme through all the works in this show.

Considering the artistic process is often non-linear and cyclical, how do you balance and sustain your creative drive amidst a distracting world and external influence?

Natalie Wadlington: It’s true that many artists can feel uninspired at times, or feel directionless. I am fairly early in my artistic career, I have been pursuing painting seriously for about 10 years. I have yet to feel like the questions in painting are exhausted; painting is both fairly easy to do, yet infinitely challenging and impossible. I’m lucky to not have too many external distractions right now in my career, but as they arise, I find going to the studio makes everything else in life more manageable.

24 x 36 x 24 in

61 x 91.4 x 61 cm

Looking forward, are there any new themes or methods you are eager to explore? Are there any upcoming projects or collaborations you are excited about and can share with us?

Natalie Wadlington: I’m going to be working on some sculptures in the next few months, more ceramics and additionally some metal work. I’m hoping to some day make an immersive installation of paintings and sculptures, where the audience can feel sort of immersed in the world I create.

Lastly, what is the significance of art to you?

Natalie Wadlington: Making art frees you, and experiencing art forces you to grow.

©2024 Natalie Wadlington