Contemporary art today is rife with contradiction. For every piece that provokes thought, there are countless others that elicit only a weary sigh. We’re inundated with artistic output; everyone wears the badge of an “artist,” and curators emerge from every corner, myself included. But does this saturation bring depth—or just clutter? More often than not, today’s art resembles a movie reboot we never asked for.

The issue boils down to accessibility—or a lack thereof. Art has grown distant, complex, and, at times, humourless. It’s as if it has forgotten its audience. Great art endures because it speaks across time, resonating not just with critics but with anyone willing to engage with it. Yet much of today’s art caters to a select few, creating a loop that alienates rather than invites.

Think about it: how many works today truly make you pause—not for a quick swipe or double-tap, but for a genuine moment of reflection? The experience has become mechanised, filtered through screens, and limited by fleeting attention spans. In the gallery, visits are often reduced to “I was there” photos—snapshots instead of memories. Art, it seems, has become something to be seen with, not something to be felt.

So is art now all just open for mischief?

Brooklyn-based art collective MSCHF might argue it is—and proudly so. They’ve built their identity on disruption, treating art as both a mirror and a provocation. For MSCHF, breaking the mould isn’t just a choice; it’s the point of their existence. They turn irreverence into a strategy, reframing the mundane and asking: can art thrive in a world of distractions, or must it become the distraction itself?

The initial spark was meeting a number of other people that I think also felt very creative and wanted to work towards this idea of making stuff in culture that really did participate directly with the culture that it was trying to critique

MSCHF

In an age of seconds-long attention spans, MSCHF refuses to compete for passive consumption. Instead, they upend expectations, drawing audiences into their world through satire, irony, and chaos.

Their work channels Marcel Duchamp’s irreverence—subverting expectations and inviting audiences to reconsider what art can be. Much like Andy Warhol’s pop-art interventions or Yves Klein’s exploration of value, MSCHF challenges traditional ideas about art, consumerism, and their intersections. Unlike their predecessors, who often spoke to elite circles, MSCHF’s work courts mainstream audiences through platforms and methods of pop culture.

Through tools of capitalism like merchandising, limited releases, and viral marketing, they critique rather than conform. From their oversized “Big Red Boot” to the notorious “Satan Shoes,” MSCHF injects satire and irony, turning cultural critique into an art form.

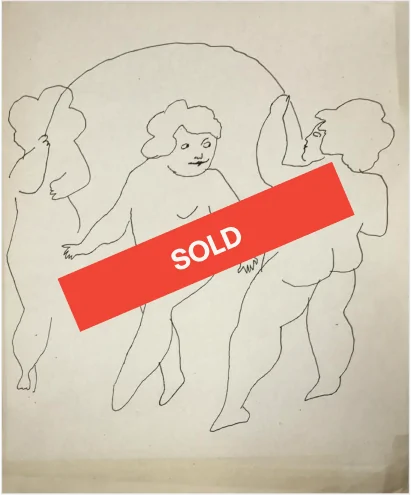

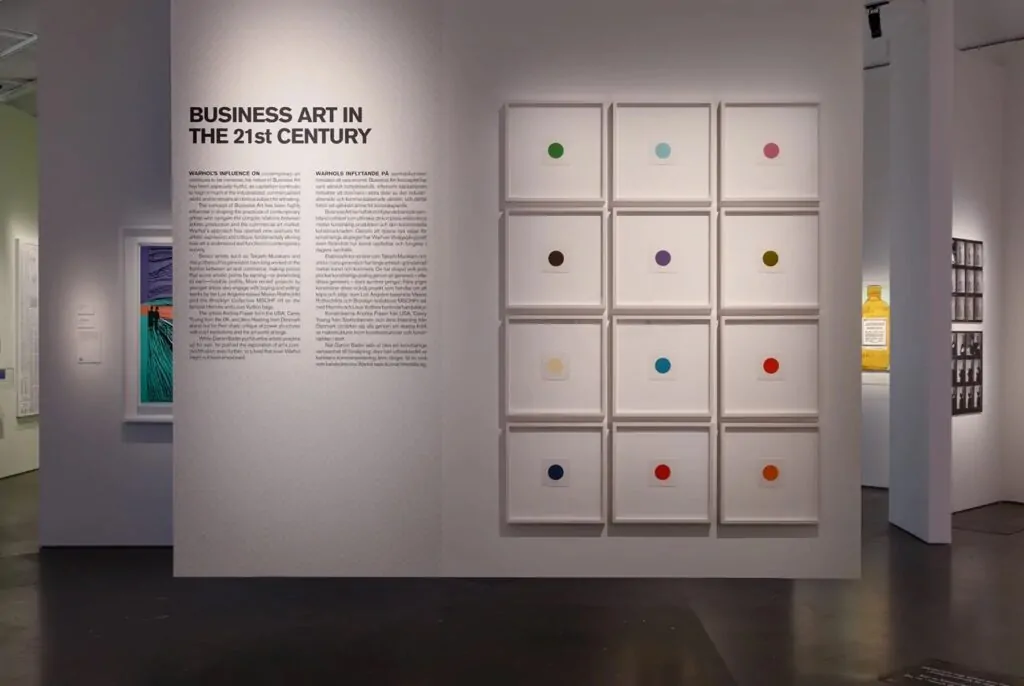

Consider their “Severed Spots” project, where MSCHF dissected a Damien Hirst spot painting, selling each coloured dot individually. The result raises a profound question: does the value of art lie in the whole, or can it be fragmented? By dismantling an iconic work, MSCHF dares us to reconsider the meaning of originality and value.

Then we got “Dead Startup Toys,” a collection of miniatures commemorating tech’s notorious failures, from Theranos’s Edison device to Juicero’s pricey juice packs—artefacts that poke fun at society’s obsession with innovation. What MSCHF achieves here is more than satire; they transform cultural hubris into critique.

Their ability to turn the prosaic into the radical moves art from gallery walls into real life. Take, for example, “Key4All,” where participants shared access to the same car. This social experiment exposed the absurdities of communal ownership, turning participants into performers to completed the piece, performance art 101.

Yet, there’s an irony here that can’t be ignored: MSCHF critiques capitalism while utilising its very tools—merchandising, scarcity, and viral campaigns—to drive their impact. Are they critiquing the system, thriving within it, or exposing its absurdity? Perhaps the answer is all three, a reflection of art’s paradoxical role today.

With growing recognition—now represented by Perrotin and hosting retrospectives worldwide—MSCHF stands as provocateurs redefining the contemporary art landscape. I spoke with four members of this 25-strong collective at Money on the Wall: Andy Warhol, an exhibition curated by Blake Gopnik at Stockholm’s Spritmuseum, to dive deeper into their practice, explore their inspirations, and discover what makes MSCHF tick.

MSCHF featured in Money on the Wall: Andy Warhol Curated by Blake Gopnik which on until the 27th of April, 2025 at Stockholm’s Spritmuseum

MSCHF has really made a name for itself with provocative, unconventional work. What do you think drove the group to start? Was there something missing in the art or social world that you were trying to address?

Jake: I’m Jake from MSCHF.

Lucas: Lucas from MSCHF.

Hope: I’m Hope from MSCHF.

Kevin: I’m Kevin from MSCHF.

Kevin: MSCHF started in 2019 originally as a group of five-ish people and we were coming from different backgrounds, not necessarily art world backgrounds. Lucas and I here are. But the other guys are coming from tech and business and marketing and advertising, all of that stuff.

So I think the thing that sort of tied us together is that we all were concerned with both making and proactively distributing work online for where we were starting from. I know for Lucas and I in particular coming from a more art world background, there was a sense that you would see people making work, we ourselves making sculpture, what have you.

And the final destination for those objects was a gallery or maybe a museum if you’re doing really well. And that was a limited audience. It was often the same audience. And often, when you had work that was sort of just investigating specific concepts or mechanisms in the world, it was living in this art space which is kind of like a – it’s like constructed space that maybe doesn’t have any overlap with the kind of like whatever in the real world is the inspiration for the work.

So we had sort of come together thinking about the idea of distribution as a core part of the concept of the things we are making from the beginning, not as something where, “Oh, I made this. Now, I figure out how it goes into the world.” But how things got, how they live, how people interact with them is kind of integral to what were making.

MSCHF x Guo O Dong

MSCHF Drop #01

Image courtesy of the artist © MSCHF

What was the moment or idea that sparked the creation of MSCHF? Did something specific push you to challenge the traditional boundaries of art and consumerism?

Lucas: I think initially, the initial spark was meeting a number of other people that I think also felt very creative and wanted to work towards this idea of making stuff in culture that really did participate directly with the culture that it was trying to critique or engage with. I think the whole show that this involved was sort of points towards that as a good strategy with making objects and making arts. In some sense MSCHF was easy name to continue working under.

Kevin: One thing that we should talk about is also kind of like there’s – one of the things that we were interested in is an idea that comes out of the traditions of like speculative and critical design, which is sort of this idea that we are in this incredibly consumer society and within that context, the forms of products, of commercial goods are extremely accessible which makes them very power communication tools.

So specifically, speculative and critical design is like an art world movement. They’re making things that look like products that then go into a gallery, which feels like it misses the point a little bit. And so when we were thinking about the objects that we’re making sort of like the forms that we’re choosing to be the vehicles for these concepts, they are often productised forms because they are very effective and we also want them to go out into the world as products. We’re doing online releases. We’re selling objects and we’re trying to use all of that to kind of like sort of Trojan horse a specific type of usually anti-consumerist absurdity into like the most mainstream spaces that we can find.

MSCHF Drop #13

Image courtesy of the artist © MSCHF

@stylingantics

Lucas: I also think and maybe we’ve mentioned it a little bit before but there’s a thought that we’re looking for controversy, and I think well, let’s see. Sometimes we are playing into controversy but we’re never really looking for legal action or anything like that. I think sometimes people assume since we’ve ended up in a few different situations that that is something we are actively seeking out. But I think we very much believed every project we’ve done were completely legally in the right to do.

I think it’s important for artists to play in spaces like this because it’s important to sort of push back on sort of prevailing culture that is hoisted upon us often by brands and other companies without our input and excessively pushed in our face and it feels like a thing that artists should be able to use and push back on a bit.

Jake: Just like expand on that. I think it is important to know like Lucas said that like outrage pretty much never the genesis of like the things that we do. We do a huge amount of like brainstorming and ideation. In all of my time in MSCHF, I can’t remember a time where going after a certain idea or going after a certain company or trying to elicit a certain response was the genesis of a project. It was more that we wanted this thing to exist and if the result is outrage or the result happens to be legal action or something like that, it’s a risk we’re willing to take to have the thing exist out in the world.

So like the steering up controversy is something that obviously gets kind of put upon us pretty often, but it has never what our initial goal is in putting something out. It’s more wanting the thing to exist and being willing to risk that controversy happens to let that thing exist.

MSCHF Drop #34

Image courtesy of the artist © MSCHF

Hope: Similar to the notion of that we’re not starting out with outreach, I think we as a collective but also the individual members of the collective, we’re subject to our own patterns of consumerism, living in a capitalist society, the different things that come across our social media and like exposure to trends.

In some ways, our reactions come from a deep understanding and intimacy of the things that are going on around us. So our work definitely does push back in a sense or like causes people to question those, but it’s always from a starting point of what we understand.

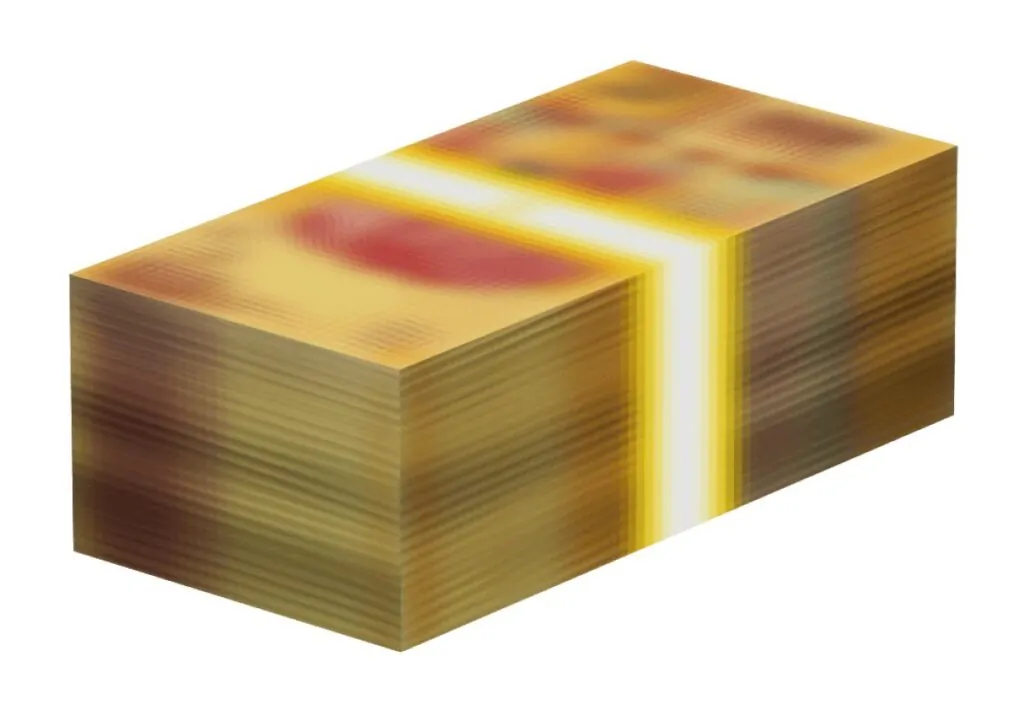

I think Blurs are kind of an interesting object to talk about here of like a phenomenon that we witnessed or maybe have been prone to but then that we took advantage of of the Blur that was just a blurry image of a stack of money that we shared exactly that on the website and it was designed to kind of make people question like the instantaneous purchase of maybe you know or don’t know what the product you’re buying is, right?

Ultimately, a lot of people exactly did that and they received a Blur work in the mail instead of like a stack of money, right? It did surprise people. Maybe some people were outraged but also, like a lot of people understood the commentary. I think one example of a phenomenon that we’re intimately familiar with that we just wanted to call attention to and wanted to adapt into a more artistic and thoughtful format to make people question.

MSCHF Drop #84

Image courtesy of the artist © MSCHF

Your work crosses into so many areas—art, commerce, technology, pop culture—and often stirs up controversy. Can you talk more about the main ideas behind your projects and how they push back against societal norms, consumer behaviour, and the idea of what art can be?

Kevin: Key for All, which I think is maybe internally one of our favourite ones. It’s from the past couple of years. It was a single car PT Cruiser 2004, not a great car but a car that a lot of people love with 5,000 keys hooked up to it so that anyone had a key. If they found the car, they could drive it. And as soon as they left it, if anyone else with a key found the car, they could hop in and drive it off.

So you have this sort of structure in which a lot of people are effectively stealing the same car from each other and it daisy chains its way around through that. The car is hooked up to a GPS so there’s always a locator for people to try to find it.

I think there’s a lot of stuff that we can talk about with this drop in terms of sort of where it went and the dynamics that emerged around it. One of the things I think it does extremely well that a lot of MSCHF drops, in fact, sort of set themselves up to do is it’s a work that’s really completed by its participant audience.

In some ways, what we’re making here is kind of like a set-up. We’re making a stage, a set of drops if you will. The performance of the work is not conducted by us. It’s conducted by the 5,000 people who have the keys to this car and it’s in fact largely out of our hands. This is a project that we thought could quite likely end as a car crashed in two days, and instead, it was on the road for nine months, and it was cruising the country, and it’s doing all of this stuff.

BY MSCHF, 2021

MSCHF Drop #59

Image courtesy of the artist © MSCHF

The life that it has is entirely due to people who are now kind of inhabiting this sort of reality that we’ve created with this car where it is an experiment in ownership. It’s also an experiment in competition, in how this group of people handles the bad actors who want to rip the GPS out of the car and try to keep it for themselves.

It’s something that all of these people are directly involved in and creating both as drivers, for example, and also as spectators. Because the spectators also get wrapped into it. There is a dynamic where once someone would try to steal the car, they often just be like relentlessly cyberbullied by the crowd of people who were observing the project and wanted the car to stay on the road. And so, they find the person who stole it, find their Google business listing and start spamming it one-star review. You have people posting these apology letters of like, “Oh, I did a bad thing. I’m giving the car back.”

Lucas: I think sort of to the point of the core of what MSCHF stands for, I feel like that project really illustrate well, just making it a conceptual object very accessible to a lot of people. I think there are a lot of pieces and artworks and objects that people design that are very unreachable by mass audiences. I feel like a large part of the practice has been sort of making work for more mass engagement.

Speaking of accessibility, a number of projects in the show are also sort of playing with that idea as well, making art objects that are normally well out of price range, easier to buy with both severed spots and possible copies of Fairies by Andy Warhol. I think those are some of the core concepts that sort of drive MSCHF.

Image courtesy of the artist

©MSCHF

Hope: That really sums up a lot of that project; adding on to the accessibility point, we sold the keys for around $18, a relatively low price point. I mean accessible than like a lot of collectables or other consumer goods. Very cheap for a car. The number of keys that we produced was 5,000 keys, which were actually purchased throughout all 50 states, even in places like Alaska and Hawaii; even though they had low chances of seeing it, they even purchased the key.

Kevin, you’ve mentioned before that a large number of people, the density of people helped the car to continue on its journey. It didn’t stay parked. That’s part of why the trip was so successful, which is the level of involvement in it.

We actually showed the car in LA earlier this year in April, and I think it’s just a nice anecdote of a lot of people who follow the car throughout its journey and, even after it got impounded in California, made a trip to come to see the car in LA. They were so excited to take pictures with it and tell stories of it even though they were spectators, so kind of that larger community involvement whether actively participating or a customer or just curious about the broader implications and the story going on.

MSCHF Drop #20

Image courtesy of the artist © MSCHF

Building on that question, The shoes—can we talk about the shoes? The Lil Nas X release marked a turning point for MSCHF in footwear; how did you see this project expanding the dialogue within sneaker culture?

Lucas: I mean the Lil Nas X one is sort of the start of that whole exploration sub-journey of MSCHF which has been more of a sculptural exploration of footwear in some sense. I also think it was sort of right at this time in sneaker culture where there were a lot of people playing around but they weren’t really playing around enough. I think we sort of fit into this interesting niche along with a number of other I think higher fashion brands that are really trying to use the form of an object and really morphed that shape was.

MSCHF x Lil Nas X

MSCHF Drop #43

Image courtesy of the artist © MSCHF

But I think we often talk about the shoe program is sculpture for our feet and I think it could be sort of read through that lens. It’s also a very good vehicle to sort of keep initiative running to some extent.

You’re part of the ‘Andy Warhol: Money on the Wall’ exhibition right now. How do you see MSCHF’s work relating to Warhol’s ideas about consumerism, mass production, and turning art into a commodity?

Lucas: I mean very concretely, we are an artist group and we are a business. We operate as such and Andy Warhol was one of the people that did pioneer that as an artistic practice and advocated for it and really participated as fully in society as possible from an artistic lens. And I feel we are walking well within that tradition.

Kevin: Just to this notion of business arch that sort of is one of the thesis of the show, there’s a sense to which – there’s a lens where we think about, “Oh, what are MSCHF drops?”

And there are a lot of them that are – they are small businesses just structured in a way that has sort of no relation to traditional business goals of long life and profit.

The car for example technically as well was – that’s literally the business ZIP car if they had exactly one car, right? We are using the same tools on constructions like down to the insurance, but to make artworks instead of to make businesses. I think really looking at both literal business structures and then also markets as working material is something that we draw a lot of inspiration from Warhol, even when we were forging his drawing, we’re doing it in reaction to a lot of these art world market mechanisms that he is also lampooning with the original discipline.

Photo Dan Kullberg

Andy Warhol Spritmuseum

MSCHF has pushed a lot of boundaries. Where do you see your work going next? Are there any new directions or mediums you’re excited to explore in the future?

Jake: In terms of new directions or mediums, we have a lot that we are working on. I can’t share exactly what those projects are but I feel like a helpful way to think about it is not necessarily like new mediums or arenas that we want to go into. It’s more that I feel like as a group, we don’t see a new arena or lane as being an Impediment to putting something out. So if we have an idea and it’s not one that we’ve done before, that doesn’t really stop us from doing it.

Last year and one of my favourite things we’ve done, we’ve put out something called Tax Heaven 3000. It was an animated dating simulator that by going through the game, you were preparing your Federal tax return. It was in the arena of taxes. That was something completely new. We had to consult with tax accountants to figure out what we were doing exactly.

But we wanted this thing to exist. We thought it was important. We said something about a certain world and the fact that it was in the arena of tax accounting wasn’t an Impediment to us doing it. So I think there are spaces that we’re like, “Oh, we want to go in there,” but also more so like, “Oh, we have an idea. It’s in this arena. We’re going to go into that arena.”

A lot of what you do is tied to internet culture and social media. Do you think MSCHF could have existed in a different era, or is your work something that can only happen in today’s digital world?

Lucas: When we started, we said a few things. We said we make work in a bunch of different genres. We initially even said we would not make the same type of object more than once and sort of existed through that. We also said we’d put stuff out on a regular time scale, every two weeks or so.

Both of these things I think have been very important for our practice is keeping things really fresh and up-to-date and current. I think there’s a thought that we are really paying attention to social media. And in fact, I think it’s sort of the opposite. I think there are a lot of artists who try to operate at the same pace that everybody is posting and working.

Personally, I think it makes the work much worse because you’re always reactive. By the time you finish something good, the moment has passed. We’re never operating that quickly. In fact, I think we’re operating on like a year, 1-year, 2-year, 3-year timelines for most projects, even if they come out within two or three weeks of each other. It’s always funny to me when someone comes up and says, “Oh, so you started working on that project when this one – the previous one ended?” We’re like, “No, that would be impossible.” But that’s a very nice thought. You think we can do that.

MSCHF Drop #117

Image courtesy of the artist © MSCHF

I do think we could have worked in a different era. I mean the methodology makes sense, any era. But I think the subject matter and the material that we’re playing with would be very different. I think today, the dynamics of social media and the internet and all the technology and culture that we’re playing with, there were different forms of that at different periods of time. Art I think often is just a reflection of that period of time for that artist. So looking back at art history, you can really see that very clearly with the types of business projects that Andy Warhol was even working on.

Kevin: I mean, you went immediately to Dada earlier, but it’s also very much – I think it’s – even if it’s sort of mechanistically totally different, it’s a similar sense of humour. It’s a similar philosophy that’s showing through in some of those works. There are a lot of things that you see in kind of art history that are like would hold up shockingly well in a contemporary climate as well.

There’s like an Yves Klein show that that’s this chequebook he had and he would like sell you a piece of art and it was just the cheque and then you tear it up and throw it in the river in France. I think that nihilism about money is like completely at home today.

The other thing you’re talking about just sort of – like how the way we’re thinking about even distributing the work would translate it. It would just be different. Just even – it’s a really short time scale but I’m even thinking of early on in our artistic practice, we were sort of like – we were making speculative companies and this was in like 2014 and it was apparent to us that if you made a nice-looking website, everybody in the media sphere online would basically take you as seriously as the realist business in the world.

It is sort of like pre-fake new era. There’s not particularly good digital literacy. If you had a website, you can get all the press coverage you wanted in the world. From then to now like that vector I think no longer works, right? All of these distribution channels are extremely tailored to their moment in time. And you don’t have to go to a historical scale to start navigating that, either.

To keep up to date with MSCHF and to participate in their drops, head to their website 👉🏿 here

©2024 MSCHF