From being crowned Sky Arts’ Portrait Artist of the Year to earning spots on the Evening Standard’s Art Power List 2023 and Forbes 30 Under 30 Europe: Art & Culture, British artist Morag Caister‘s intimate portrait paintings have unquestionably riveted the art world’s attention.

Image courtesy of the artist

Drawing and painting always felt liberating and magical when I was younger, and it just felt like the best way to describe the things I understood.

Morag Caister

Caister’s practice delves deeply into the intricacies of human nature, exploring its layers through figuration, portraiture, and the nude, with a confessional intimacy, in her sittings, stories are shared, and connections are forged with each painting.

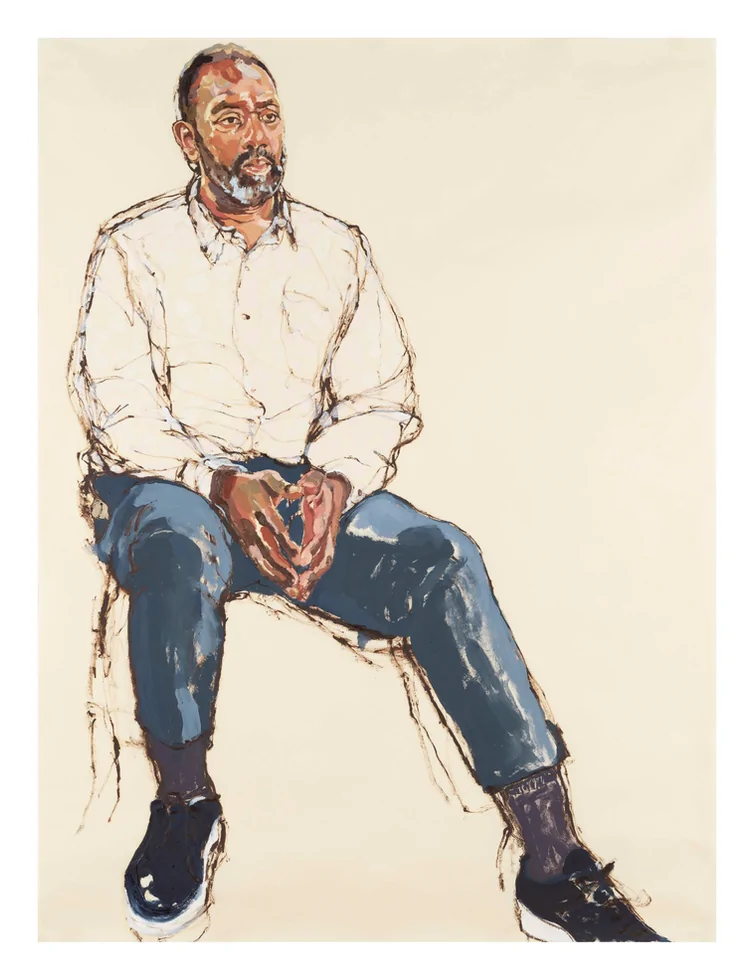

These emotionally charged works bear truth rather than perfection, her sketch-like application of paint renders her figures in a raw, almost skeletal form, echoing the rebellious spirit of Expressionist painters.

Exaggerated lines frame an earthy palette as colors bleed into each other, creating warmth and density that envelop both the sitter and surroundings, disarmed by vulnerability, the subjects appear relaxed and unguarded, surrounded by the subtle objects of their daily lives, as if the world outside the canvas simply fades away.

For Caister, drawing and painting have always been acts of liberation and transformation—a way to articulate what she understands and to bring her imagination to life—a curiosity that has continued to flow through her practice since childhood.

Her latest exhibition at London’s Rhodes Contemporary Gallery, Peacetime, features a series of humanizing portraits set against everyday backdrops, capturing moments of stillness and acceptance amidst the chaos of contemporary life.

Caister speaks to a primal sense of connection, prioritizing emotional resonance over precise reality, balancing vulnerability and trust in a blend reminiscent of the intensity of Austrian Egon Schiele and the emotional honesty of American Alice Neel—yet her expression is entirely her own. The result is introspectively rich, inviting us into the subtleties of human nature in the sense of personal space.

Since graduating from the University of Brighton in 2019, Caister has been on an upward trajectory, receiving numerous accolades and awards.

Now her works are now held in prominent collections like the National Portrait Gallery and Soho House, solidifying her reputation as an influential and compelling voice in contemporary portraiture—definitely an artist to watch as time progresses.

Morag Caister: Peacetime is on view until the 5th of October 2024 at RHODES

Hi Morag, thank you for joining us. To start, could you share your journey into the arts? Were there any moments or experiences that led you to pursue the path of an artist?

Morag Caister: Hello and thank you for having me. Drawing and painting always felt liberating and magical when I was younger, and it just felt like the best way to describe the things I understood. It would feel kind of urgent to share certain stuff that I’d pick up on about someone or something, as if to say, “I noticed this, did you notice it too?” I feel it comes from wanting to have a voice and engage with things. Going to big museums and galleries that were purely there to display art was mind-blowing.

I thought of adults as very serious people, and it was so crazy to me that they had made time and room for art. And not just that, but the people making the art were also adults. I think it made me feel like what I was doing was worthwhile and kind of grown-up. I come from a creative family, and I was lucky to be supported in going in that direction.

You’re mostly known for intimate portrait paintings guided and inspired by your deep interest in the intricacies of human nature. Could we delve into your practice, inspiration, and approach to your work?

Morag Caister: My practice involves painting people from live sittings, using line and patches of colour to build up a composition and working with oils on paper or linen. I feel it’s inspired by a love of experiencing new things and fantasising about the things that can’t be experienced. When I was younger, it would be stuff like flying, being able to breathe underwater, or being able to make sweets appear out of thin air. Then it became a little more existential, and my mind would be blown by the way we could never experience things from other people’s perspectives.

There was a limit there, and painting people felt like a way to overcome that limit. I was close to studying philosophy at uni, and I’m glad it didn’t happen because instead, I was able to put all of the curiosity into my practice, which really is still looking closely at things, ideas, and people. The interest in people and our nature comes from generally getting a lot out of understanding more about where and who we are and how everything works, and painting became the perfect place for me to join these things together.

I value the connection it gives me too. Elif Shafak is one of my favourite writers, and in her manifesto “How to Stay Sane in an Age of Division,” she says that sharing stories brings us closer together and untold stories keep us apart. It was in reference to the emotional distance we can begin to develop when we get used to hearing huge statistics rather than learning about personal stories. When I’m painting someone, I feel very close to who they are, and I get a sense of what kind of life they’ve had.

It’s like I’m witnessing their story. It’s a very moving experience, and it has only ever brought me more compassion and patience for what we’re like as people, and I think the sitters have a similar experience. So, these are things that motivate and inspire my practice.

You describe your portrait sittings as akin to therapy sessions or confessional moments. Can you elaborate on the role of the artist as a confidant or therapist in the creation of these portraits?

Morag Caister: I feel it’s the situation itself that becomes the confidant/therapist, and it allows both me and the sitter to have that special space. Often our interaction becomes frank and simpler, almost like we are both committed to giving the painting the best chance of becoming filled with something truthful, and that reminds me of the kind of upfront honesty people have when they’re hoping to get answers or solutions.

I feel a sense of duty with it too. I only want to paint people when they’re at ease, and sometimes that leads to emotions coming to the surface. However, I don’t feel good about someone being uncomfortable and then painting them in that state of discomfort.

How do you create an environment that encourages such deep reflection and honesty from your subjects?

Morag Caister: I try to make it clear that acceptance and curiosity form the work. I think it’s a relief to be told, “For this, you have to be exactly who you are in whatever form that is in this moment.” The person being there and allowing me to look at them closely is the act of honesty. After that, whether they are more open in conversation or on the quieter side are details of their personality and secondary elements in the work. Firstly, it’s their presence and aliveness.

In addition, the cyclical habits and behaviours of daily life are hinted at in your paintings. How do you decide which aspects of these routines to highlight, and what do you believe they reveal about the human condition?

Morag Caister: It feels important to keep pointing out the things that we all do, as if to point out the things we have always done. I’ll have phases where a particular habit sort of feels like it’s shuffled to the front, and I’ll delve into it for as long as it’s there. Something about people at rest in the home environment is very emotive for me at the moment; in the last few years, I don’t remember not having the urge to draw/paint figures lying down and stretched out.

It’s acknowledging the peaceful side of who we are as people, seeing as everyone has a version of doing this. I think it’s the needing of rest I find so moving currently, because I’ve always been conscious of our capacity for conflict and this other part is evidence of our softness and it represents the possibility of peace.

Key aspects of your portraits, like the backdrops and the subtle inclusion of domestic motifs, seem to play an integral part in the storytelling. How do these elements contribute to the overall narrative of your portraits, and what do they signify about the ‘quiet disorder’ of everyday life? What importance do they hold in the overall composition?

Morag Caister: I started including mess in the paintings because it kind of felt like hinting at the chaos that might exist outside the edges of the paintings. I liked the idea of this taking the quiet form of everyday things like crumpled towels or unfolded clothes because they felt like traces of disorder in the home environment, somewhere that we hope is safe. Including them felt like addressing the possibility that hangs in the air that things could go wrong, the sense that we teeter on the edge of chaos a lot of the time. Those things just need keeping in check and staying on top of like laundry. When it accumulates, it feels bad, it taints our space and time for rest.

Your upcoming exhibition, “Peacetime,” at London’s Rhodes Contemporary, explores the dualities of human existence through a series of new works. Could you share more about the exhibition’s essence and the featured works?

Morag Caister: I chose the title peacetime in the sense that when we are peaceful, it’s a temporary state, like the way that we go to bed at night and wake up in the morning, the sun goes up and down, the sea goes in and out. I wanted to recognise the pushing and pulling of stillness vs movement, rest vs action, peace vs conflict. I think I wanted to say something about us being multifaceted and our nature being capable of sliding up and down the scale and for the works to simply recognise that. I’d like the work to encourage imagination and compassion in regard to others and ourselves.

Having won Sky Art’s Portrait Artist of the Year and received other recognitions, such as Forbes 30 Under 30 Europe: Art & Culture, and inclusion in the Evening Standard’s Art Power List 2023, do you feel a shift in how you approach your work now compared to before these honours?

Morag Caister: Yes, they have hugely shifted my confidence in my work; it’s been validating for my practice and has urged me forward to paint more ambitiously and accelerated the speed at which I can do it, so it’s gifted me with more time as well as many more opportunities which I’m endlessly grateful for.

Building on that question, do you think these accolades influence how people interpret your art and your role as an artist?

Morag Caister: It has put my work in front of an audience that it wouldn’t have reached otherwise and I think it encourages those people to give it a chance.

Looking ahead, are there any particular themes or subjects you are eager to explore in your future work?

Morag Caister: Yes, right now, I’m interested in pursuing these figurative sofa-based works and the threads that keep coming off them, and I am excited for when it will become something else. I have ideas for making a series of miniature works that stay in the home environment centring around themes of childhood independence and imagination, as well as ideas using portraits to celebrate groups of people such as female writers or working with a charity and bringing awareness to a cause.

Finally, please share the guiding philosophy behind your art. Additionally, could you elaborate on art’s significant role in your life and career?

Morag Caister: When we make art, I think it comes from the purest part of who we are. For me, it has been expressing my inner world, and engaging with art has brought me joy and delight throughout my life. It’s helped me consider things I don’t understand and opened my eyes to the reality that different worlds exist, which makes communicating with someone even more special when it works.

©2024 Morag Caister