In an age hooked on dopamine hits, algorithmic approval, and swipe-sized intimacy, British artist Mitch Griffiths moves against the current—with the slow, deliberate gravity of oil paint. His canvases, rendered with Old Master precision, refuse to be ignored. They demand time, attention, and unease.

Griffiths paints like someone out of time, yet acutely attuned to the present. His style harks back to the Renaissance, with its compositional weight and technical discipline, but his subject matter is unmistakably modern.

When I’m standing at an easel, painting, I tend to inhabit my own little pocket of reality, trying to create my own reality on the canvas. I think everybody has these different levels of reality.

Mitch Griffiths

Fast food wrappers, branded logos, and faces etched with 21st-century fatigue emerge beneath layers of varnish and shadow. His work explores themes of isolation, obsolescence, and the blurred boundaries between consumerism, surveillance, and the curated self. Entirely self-taught, Griffiths is uninterested in irony or visual quotation. “When I’m standing at an easel, painting,”

he says, “I tend to inhabit my own little pocket of reality, trying to create my own reality on the canvas. I think everybody has these different levels of reality.” His practice is both sincere in its ambition and rigorous in its execution.

Mitch Griffiths

Image courtesy of Halcyon

Each painting is built slowly, methodically, through layers of oil that give his figures the

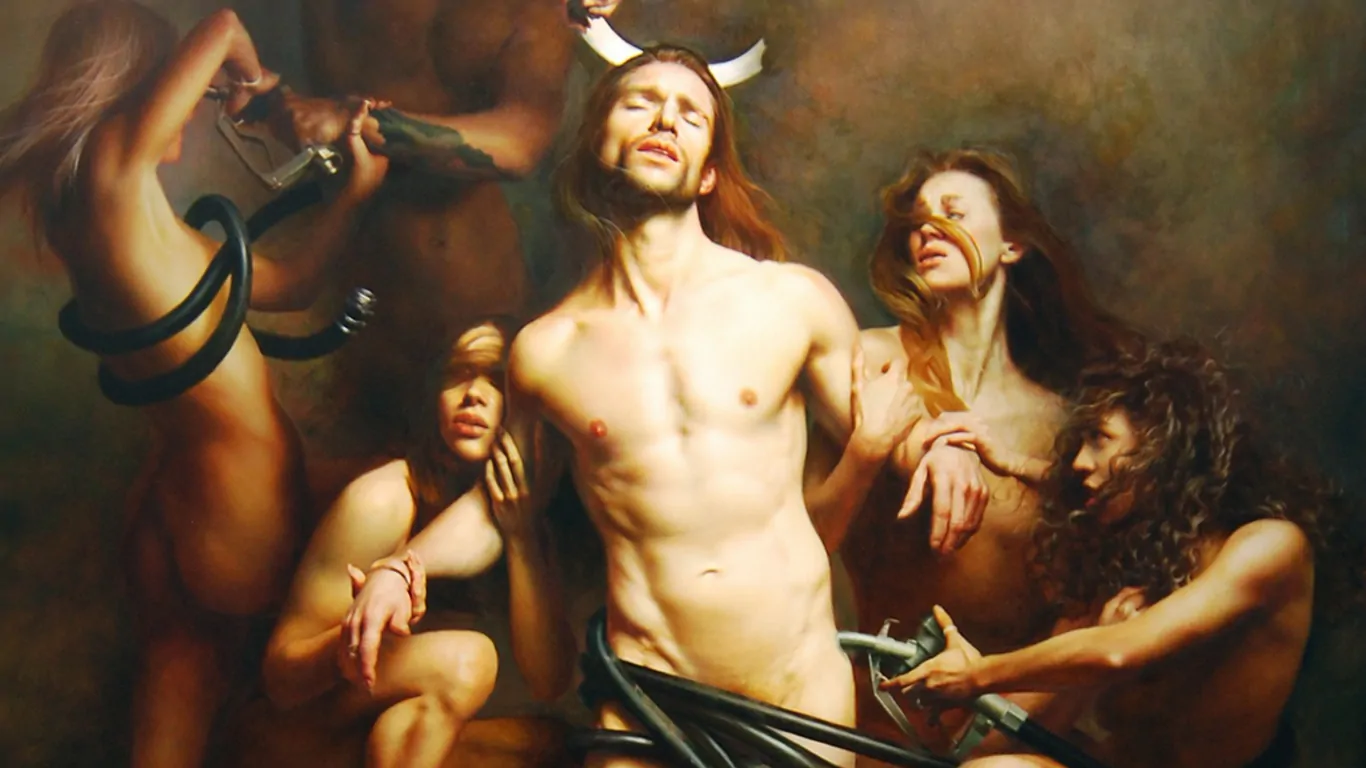

weight—and fragility—of flesh. This collision between the classical and the contemporary finds perhaps its starkest expression in Destroy Me Again (2024), a painting that delves into power and pain with operatic intensity. At its centre stands a bare-chested man, arms outstretched in a cruciform pose, bound by black industrial hoses. Around him, nude figures claw in a chaotic frenzy, while skulls below evoke the slow decay of systems—ancient, modern, or both.

The lighting is painterly yet cinematic: a chiaroscuro of moral ambiguity. No one emerges blameless—not the figures, not the viewer. This painting doesn’t raise its voice; it beckons, then unsettles. That may be its most disturbing quality. Griffiths uses light and shadow as emotional instruments, not just stylistic ones. He draws heavily on the tradition of chiaroscuro—not to imitate Caravaggio, but to deepen the emotional resonance of his scenes. In his Unreel series (2024), subjects appear caught in moments of private tension, their faces lit with the starkness of truth, suspended somewhere between calm and crisis.

Mitch Griffiths

Image courtesy of Halcyon

At a time when much figurative art either leans into classical nostalgia or retreats into

irony, Griffiths occupies a rare space. His work is serious in its technique and unsparing

in its subtext. It reminds us that the human body—long central to the story of Western

art—still has new traumas to carry, and new truths to reveal. His latest works appear in Sacred and Profane, now showing at Halcyon, an exhibition that examines how artists reinterpret religious iconography for a secular age. At its centre is Shrine (2022), a portrait of a woman with a drone resting on her head like a crown.

Image courtesy of Halcyon

She gazes out, calm and commanding, a modern Madonna encircled not by saints, but by the instruments of war and surveillance. Reverence and dread share the same frame. In Griffiths’ work, nothing is sacred—but everything is taken seriously. And within that seriousness lies a quiet kind of faith. Not necessarily in religion, but in painting. In light. In flesh. In the idea that a hand and a brush, when wielded with intent, can still tell us something vital about who we are.

Exhibiting alongside Griffiths in Sacred and Profane, Colombian artist Santiago Montoya employs banknotes as his canvas, reimagining currency as a vehicle for sharp, often satirical critiques of capitalism. Together, the two artists navigate the tensions between history and modernity, urging viewers to reconsider entrenched notions of value, legacy, and the constructed narratives of everyday life.

Sacred and Profane is on view at Halcyon, 148 New Bond Street.

©2025 Mitch Griffiths, Halcyon