Brooklyn-based artist Matt Kenny explores the history and tragedy that underlie contemporary urbanism by combining meticulous research with various styles. An unorthodox thinker, Kenny’s practice examines the constantly changing cityscape and what lies beneath its perpetually morphing veneer.

An avid reader and investigator of American cataclysms, Kenny has a keen interest in the significance of 9/11, the evolution of New York City’s skyline, and particularly the structural response in the shape of the World Trade Center’s “Freedom Tower”.

What I am inclined to do is take one subject and come at it from a couple of different directions and see where the subject takes me

Matt Kenny

A crucial ingredient in the artist’s current work, yet his paintings don’t concentrate on divulging the totalising truth about these earth-shattering events. Kenny’s photorealist scenes portray the iconic tower as a vivid caricature in a monstrous manner seen from a street-level perspective.

We managed to catch up with Matt Kenny to learn more about his new series of works, practice and more.

Q: Hi Matt, can you please introduce yourself for those who do not know you?

A: My name is Matt Kenny. I was born in Kansas City, Missouri, raised in New Jersey, and lived in New York City for over 20 years. I’ve been showing pretty actively since 2014, primarily with Halsey McKay Gallery and The National Exemplar.

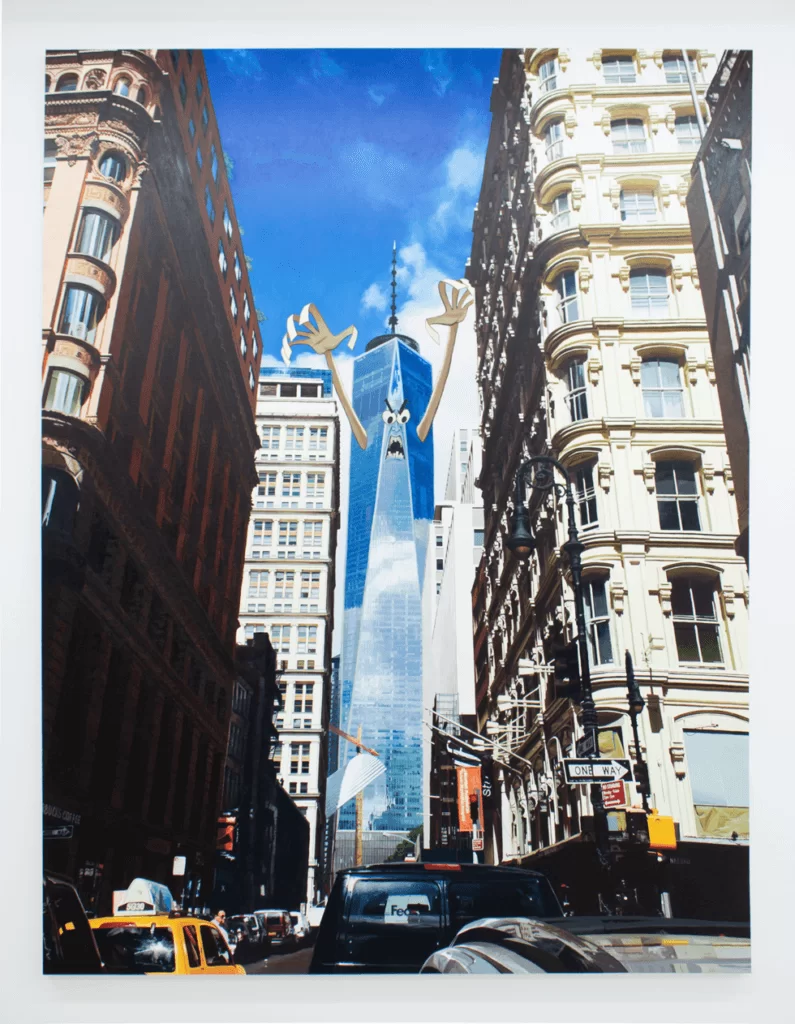

Oil on canvas 40 × 30 inches

Courtesy of the artist and Halsey McKay Gallery

Q: Can you tell us how you got started in arts and why you decided to become an artist?

A: It started young my parents picked up on my interest in drawing from a young age, and I was encouraged by them and my teachers. My parents brought us to museums. From an early age, I was in love with New York City. That was essential. Loving New York made me all the more susceptible to its mythical art histories. I was also lucky to have some really good, clued-in art teachers as I came up through school. I went to a public school in a town on the border of the burbs and farmland and won the lottery in terms of art teachers.

I still think about a moment when our art history teacher presented a Mondrian painting as a response to World War I. We trusted her enough to really try to go there and let the possibility of that idea sink in. Those were vivid, dignified ideas in an often dreary day at school. I was a terrible student, except in those rooms. The art department had a strong photography program. Even my painting teachers were committed photographers.

What that meant was these teachers were interested in art that was still unfolding in the world. We weren’t just talking about golden oldies. In retrospect, I think that was really important. From there I went to RISD, and I had classmates whose company I enjoyed, who I learned from and took seriously. A large number of us moved to New York City and are still kicking around making things. Being around people who share your concerns is crucial.

Q: Can you tell us about your practice, your creative process, what inspires your work, and the direction your work is going?

A: Since around 2014, a significant portion of my work has been centred on the World Trade Center. In 2015 I showed a series of paintings of One World Trade Center made into a cartoon-ish angry man with bad teeth locked in a somewhat plausible cityscape. Following that, I made paintings of One World Trade Center, sans the face and arms, as seen from a train window in New Jersey’s Meadowlands. In 2017 I published Coercive Beliefs, a non-fiction poem that told the story of Omar Abdel-Rahman, a cleric who was accused of being at the center of the 1993 World Trade Center attack.

Over time it turns out that what I am inclined to do is take one subject and come at it from a couple of different directions and see where the subject takes me. Subjects naturally lead to other subjects, often in surprising ways. It has surprised me to find myself making landscape paintings, or developing an obsession with Pissarro’s cityscape paintings, or spending a couple of weeks researching Anwar Sadat. I’ve found that cycling through these approaches, in addition to intensive research, helps to keep me excited about the material.

Recently I’ve been working on a sequel to Coercive Beliefs focused on Rudy Giuliani. Researching not just Giuliani but Ed Koch, David Dinkins, and Bloomberg, thinking about the city from the point of view of the mayor’s office has taught me so much about the city. It has made walking around the city more vivid, and I seek out that place where the inspiration and the work develop a feedback loop. I am about to revisit the view of the World Trade Center from the Meadowlands. I’m busy exploring these parameters that I’ve set for myself in the last couple of years.

Q: Your current exhibition, World Trade Center Paintings at Halsey McKay Gallery, explores the history and tragedy of the iconic World Trade Center in a series of urban caricature works. Can you tell us some about the exhibition and the significance of these works?

A: I had been following the rebuilding effort at Ground Zero pretty closely. There was a stretch of time where the city sought to air the process of deciding what would be built on the site publicly. In retrospect, it is actually pretty impressive how democratic the World Trade Center design process hoped to be. As One World Trade Center started to rise, you could see the paranoia in the bones of the building.

The base is this dense web of steel and cement that is designed to protect the building from truck bombs. The idea that this bunker would eventually be cloaked in this mirrored skin that presented a false sense of airiness and transparency was fascinating. Around this bunker was another web of fencing, surveillance cameras, images of future building sites and a statue of a guy on a horse with a machine gun. It was insane down there. Do I blame them for building a camouflaged bunker with an office tower on top?

No, on that site, it seems to me a camouflaged bunker is the best you could hope to do, which is a wild place to be both practically and theoretically. Welcome to the new world. It spoke to other changes taking place in the city. The militarization of the police. The vulnerability of public discourse to paranoia and division. The financialization of the economy. Wild speculative real estate projects. The radical shifts in the economic character of the city. For me, Ground Zero in the twilight of the Bloomberg administration distilled these trends.

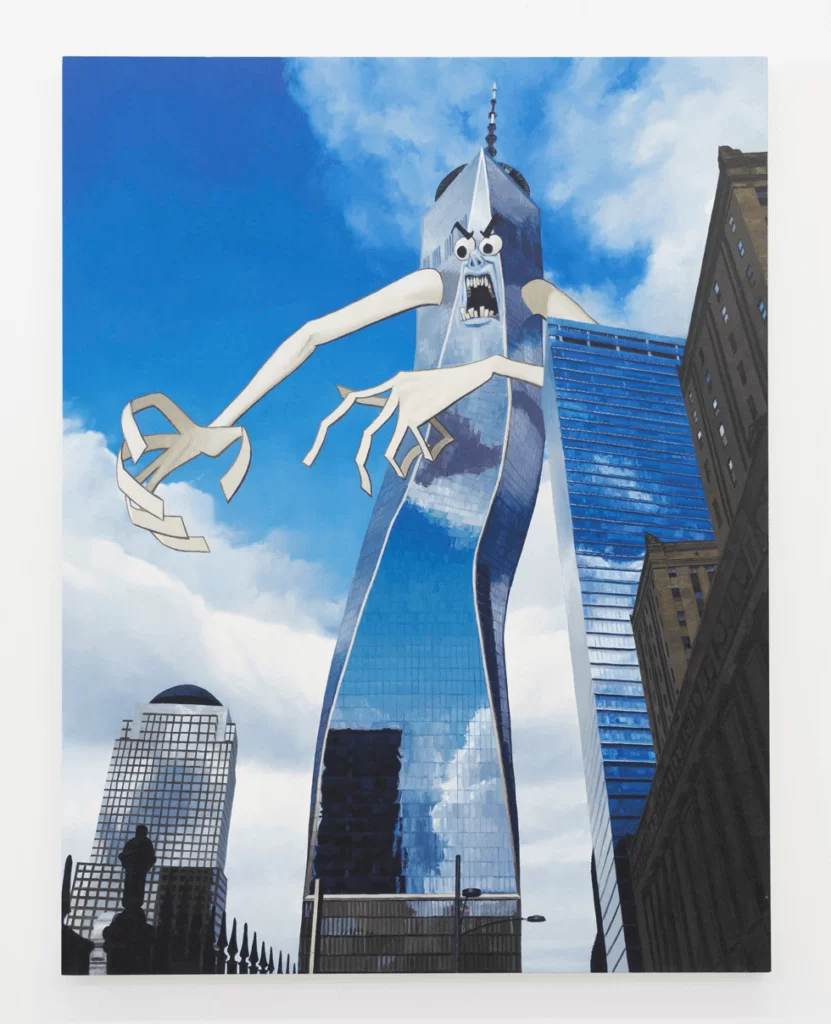

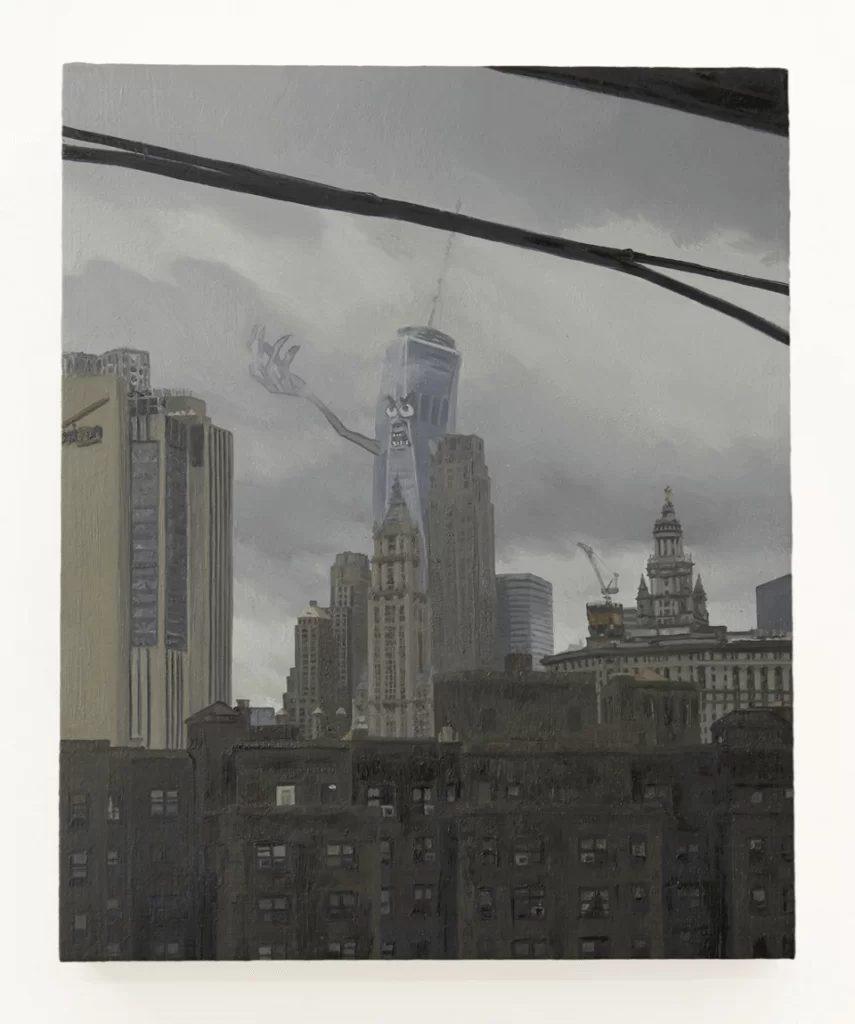

Around the time that One World Trade Center was topping out, I saw something in Houston, Texas, that blew my mind. On lawns all across Houston, there were signs protesting a proposed residential high rise that was being planned for a neighbourhood that primarily consisted of single-family homes. These signs, designed by Marshall Wilson, a Houston architect, featured a simple tower with bulging eyes and floppy hands terrorizing a wealthy Houston neighbourhood. I absolutely love these signs. It didn’t take long for me to start putting Wilson’s monster on One World Trade. Pretty quickly, my 1WTC monster evolved away from Wilson’s protest posters and my own cranky menace, with visibly apparent psychological problems emerged.

The paintings really are about One World Trade Center and its awkward relationship to the 9/11 attacks. The fact that an office tower with its vaguely antagonistic size, stripped of its early symbolic name — the Freedom Tower — stands over the 9/11 memorial as a muted expression of resilience is itself an emotionally complicated banality.

Oil on panel 10 x 8 Inches

Courtesy of the artist and Halsey McKay Gallery

The paintings address that area where a horrendous disaster has started to recede into the past, and time has brought us waves of new glass buildings and new disasters. For me, painting cityscapes is a way of thinking through and making sense of the city. In the past, I’ve said that the face I put on the towers is a false observation, an imposition. The true personality, were it to have a more appropriate face, is hard for me to imagine. The elusive character of the new World Trade Center is one of the reasons the site continues to fascinate me.

I still struggle to make sense of it. Putting a false face on it has revealed to me how elusive the building really is. As I’ve revisited the monster, the tower itself has receded, and the city has begun to take up more of the paintings. I’ve been focusing on windows, rooftops and streets, all of these features that have a palpable sense of life and history. There is a shift from meditating on the World Trade Center in and of itself to meditating on the WTC in New York City. That contrast reveals that somehow the brick and iron tenements or windowless Madison Square Garden are somehow more transparent, more legible than the psychic opacity of mirrored curtain walls of the office buildings at ground zero.

Oil on canvas 54 x 72 inches

Courtesy of the artist and Halsey McKay Gallery

Q: They say the studio is the sacred template of creativity. What are the three things you cannot live without in your studio?

A: My studio is pretty straightforward. I have a computer desk on wheels with a glass top that is a great palette. I like to have t-shirt rags on hand — even though it isn’t absolutely necessary I really feel it when I don’t have any—Saran wrap for storing paint.

Q: What’s next for you as an artist?

A: For the fall, I’m working on a show and a publication with F, Adam Marnie’s gallery in Houston, Texas.

Q: Lastly, what does art mean to you?

A: That is a huge question. I love examining artworks, and I love making artworks too. I’ve gone to great lengths to make it so that engaging with artwork is my life’s central activity. I’d like to leave it at that.

©2022 Matt Kenny, Halsey McKay Gallery