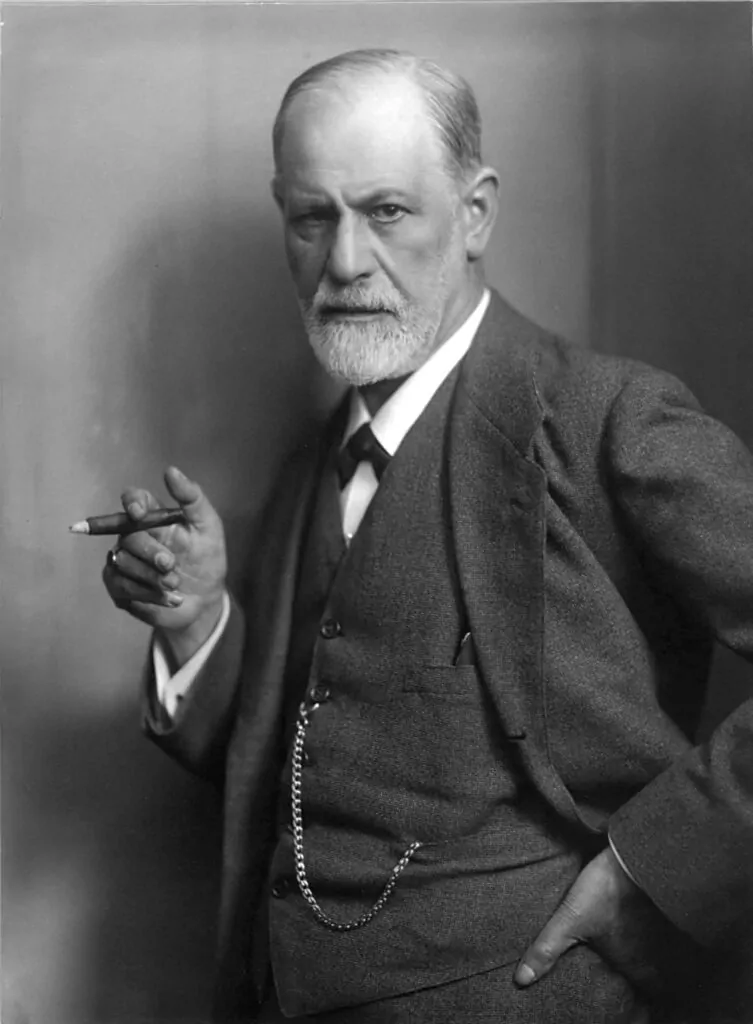

Trailblazing neurologist and father of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud‘s work has left a legacy that continues to ripple through the world of art, science and modern life. Freud’s exploration into the mysteries of the unconscious mind found a natural ally in Surrealism, an art movement coined and championed by André Breton in the early 20th century.

Freud‘s theories underpinned artists such as Salvador Dalí and René Magritte practices; the artists’ striking visuals of the bizarre and the uncanny were hallmarks of the subconscious mind as Freud described it.

Freud’s intellectual impact, however, extended far beyond painting. His theories profoundly influenced literature, theatre, and cinema, sparking a cultural shift toward introspective investigations of the human mind. Seminal texts like The Interpretation of Dreams (1899) and Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920) provided frameworks for understanding the hidden forces that shape the interiors of the mortal mind.

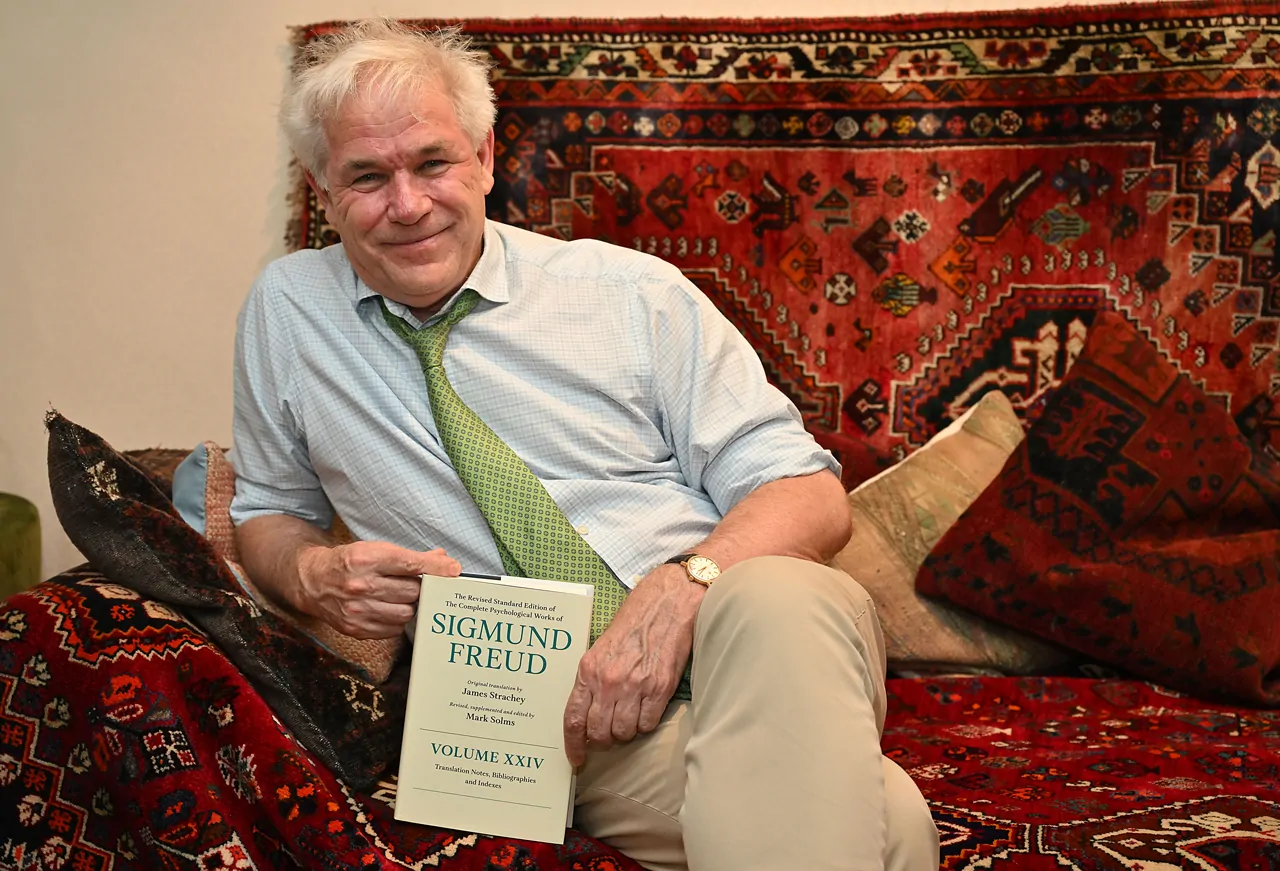

I have made Freud more readable for contemporary audiences by modernising the English spelling and grammar. I have brought the editorial apparatus up do date

Mark Solms

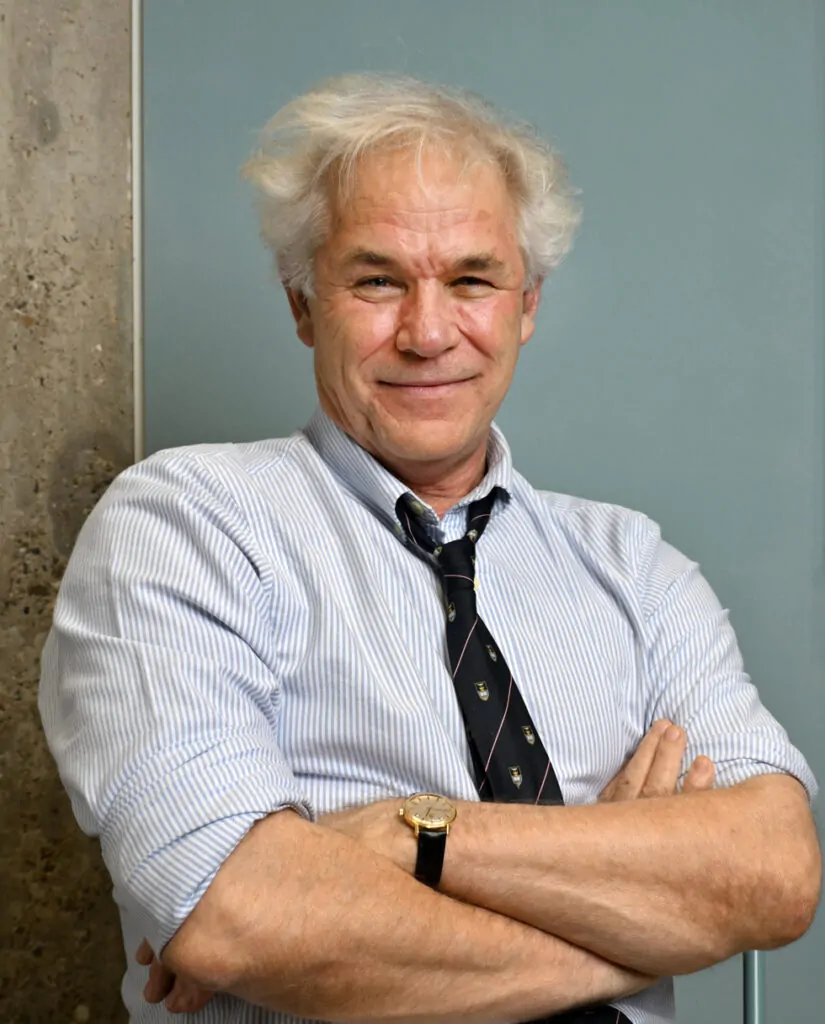

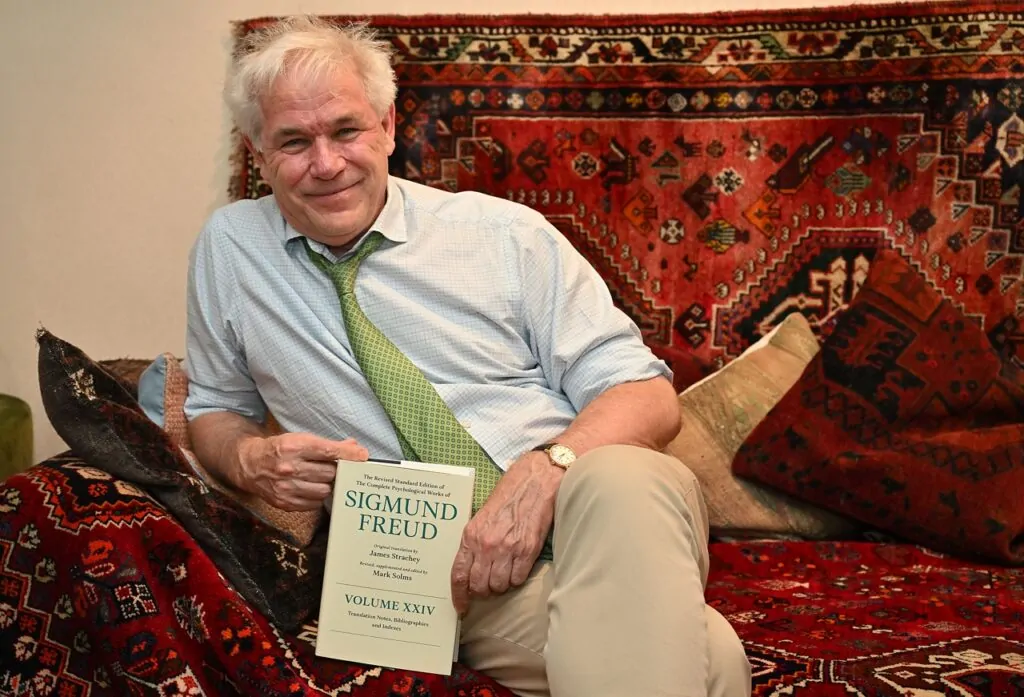

This year, as we commemorate the 50th anniversary of the complete release of Freud’s works, we are presented with a renewed opportunity to reflect on his transformative contributions. A newly revised standard edition of Freud’s complete works, edited by renowned psychoanalyst and neuroscientist Mark Solms, offers fresh insights into Freud’s legacy. Solms, known for integrating contemporary neuroscience with psychoanalytic theory and discovering the forebrain mechanisms of dreaming, continues expanding on Freud’s groundbreaking work.

We spoke with Solms to explore the enduring influence of Freud and the continued relevance of his theories in art and science today.

Hi Mark, thank you for speaking with us. For those who may not be familiar with your work, could you please introduce yourself and give us a brief overview of your career and contributions to the field of neuropsychoanalysis?

Mark Solms: I completed my neuropsychological training in 1985. However, I was frustrated by how little ‘psyche’ there was in neuropsychology – surely the most interesting thing about the brain is that it has subjective experiences – so, much to the dismay of my neuroscientific colleagues, I decided in 1989 to train also in psychoanalysis. From then on, I made it my life’s work to integrate these two fields: to bring psychoanalytic methods and theories into the neurosciences and vice-versa. I made interesting observations over the years, starting with my discovery of the brain mechanisms of dreaming and culminating in my most recent work on the affective basis of consciousness.

You have been instrumental in integrating contemporary neuroscience with psychoanalytic methods and theories. Could you tell us how this integration has influenced the revisions and new translations in the Revised Standard Edition (RSE) of Freud’s Complete Psychological Works? Are there specific instances where modern neuroscience has provided fresh insights into Freud’s theories?

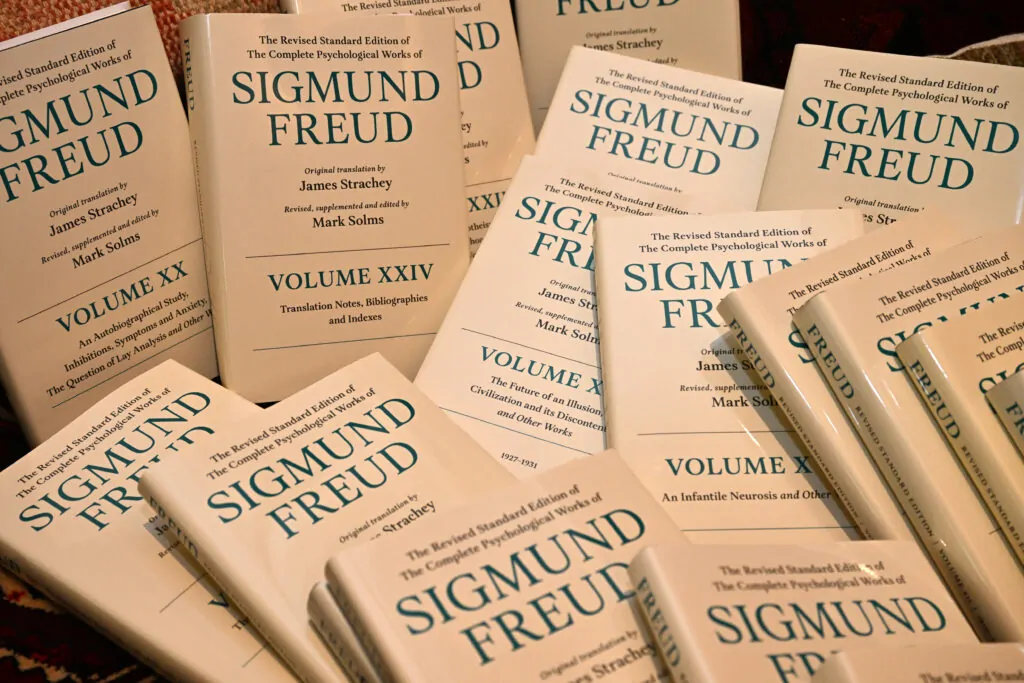

Original Translation by James Strachey

Revised, supplemented and edited by Mark Solms

Mark Solms: Modern neuroscience has corrected many of Freud’s theories. For example, there are at least seven emotional drives that motivate human (and all mammalian) behaviour, rather than just the two that Freud identified. Modern neuroscience has also confirmed many of Freud’s basic claims.

For example, nowadays we all agree that many mental functions are performed

unconsciously, that early childhood experiences are pivotal for later mental development, and that dreams are motivated mental processes. However, these new insights did not influence the RSE very much. I corrected the translation of Trieb, which Strachey translated as ‘instinct’ and I have since translated as ‘drive’, because instincts and drives are very different things, neuroscientifically speaking. For the most part, modern neuroscience permeates only the editorial apparatus of the RSE.”

The RSE includes extensive new annotations to address conceptual and lexicographic ambiguities in Freud’s original texts. What were some of the most significant ambiguities you encountered, and how were these clarified in the new edition?

Mark Solms: The strongest and most widespread criticism of Strachey’s translation concerns Freud’s technical vocabulary. Where Freud used ordinary, descriptive German terms, Strachey used neologisms derived from Ancient Greek and Latin. Thus, where Freud wrote Besetzung (an ordinary word meaning ‘occupation’) Strachey put ‘cathexis.

Where Freud wrote Anlehnung (an ordinary word meaning ‘leaning-upon-ness’) Strachey put ‘anaclisis’, and where Freud write Ich (meaning simply ‘I’) Strachey put ‘ego’. This criticism is based on a lack of familiarity with the conventions of German versus English scientific writing. Neuroanatomy was the science with which Freud was most familiar when he forged his psychoanalytic terminology.

However, to use some more familiar examples, what German chemists call Wasserstoff (meaning simply ‘water stuff’) and Sauerstoff (meaning ‘sour stuff’) we English speakers call ‘hydrogen’ and ‘oxygen’, respectively. These are the sorts of issues I clarify in the RSE.”

Credit Max Halberstadt

Freud’s writings, particularly on the unconscious mind, have had a profound impact on the surrealist art movement. Can you elaborate on how these theories shaped surrealism, and how you see this influence evolving with the release of the RSE?

Mark Solms: The surrealist art movement was predicated directly upon Freud’s discoveries and methods. For example, the dream-like landscapes of Dali and De Chirico are literal depictions of the inner world that Freud explored, the uncanny juxtapositions that inspired some of Magritte’s most famous works draw upon Freud’s theories concerning das Unheimliche, and Breton’s automatic writing was a direct application of Freud’s method of free association. Without Freud, there would have been no surrealism. The current renaissance of interest in Freud (prompted by no means solely by the appearance of the RSE!) might very well be reflected in

a renewed version of surrealism.

In contemporary art, how do you perceive the legacy of Freud’s theories on the unconscious mind? Are there specific modern artists or art movements that have been particularly influenced by his work?

Mark Solms: I think the German and the abstract expressionists were every bit as much influenced by Freud’s theories as were the surrealists. They were just less explicit about it. I think the same applies to the Dadaists. If you think of the influence upon contemporary art of just these three or four movements, then the full extent of Freud’s influence comes into view. I think that influence is so all-pervasive now that we do not even notice it anymore.

The release of the RSE coincides with the centennial of André Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto and the 50th anniversary of the final piece of Freud’s complete works. How do these milestones highlight the significance of releasing the RSE now?

Mark Solms: There was no conscious intention for these two events to coincide (if you will excuse the pun).

What can contemporary audiences and scholars gain from this new edition that might have been missed in previous decades?

Mark Solms: I have made Freud more readable for contemporary audiences by modernising the English spelling and grammar. I have brought the editorial apparatus up do date (incorporating the 60 years of Freud scholarship that accumulated since the publication of the old SE). Thus, for example, it has been possible to unravel the various disguises and distortions that Freud introduced to protect the confidentiality of his now-long-dead patients, thereby shedding important new light on his famous clinical case histories.

I have revealed the many continuities between Freud’s neuroscientific and psychoanalytic works, which previously remained hidden from view; and I have shown how he anticipated many modern neuroscientific discoveries.

I have provided much better (and more interesting) illustrations. I have provided a proper index to each volume and to the 24 volumes as a whole (I have to say, the previous indexes were really poor). I have radically updated the bibliography of Freud’s works, which is now almost five times longer than the previous one. But perhaps the most important gain is the one that you address in the next question…

The RSE includes 56 essays and letters not previously included in the Standard Edition. Can you highlight some of these additions and discuss their relevance to understanding Freud’s impact on both psychology and the arts?

Mark Solms: Some of the most interesting new works concern early lectures that Freud gave on hysteria and some other neuroses, a new clinical case study, a report on his own typical dreams, some strong attacks on the homophobic views of his colleagues (including his psychoanalytic colleagues), a defence of women’s rights with respect to marriage law, a blistering critique of everything American (!), a psychological analysis of President Woodrow Wilson, some moving letters written to Einstein, a new theory of Christianity — in which he claimed that priests suppress their homosexuality by identifying with Christ – and, finally, some humorous remarks upon the attitude of Jews towards death.”

As The Interpretation of Dreams is one of Freud’s most influential works, it has inspired numerous surrealist artists. How does the revised translation in the RSE potentially alter or deepen our understanding of this seminal text?

Mark Solms: I have mentioned already that I inform readers in my editorial introduction of subsequent developments in the science of dreams, and of the remarkable support that new discoveries provide for his (apparently unlikely) theoretical claims. I draw attention also to the fact that Freud reported dreams in the present tense, whereas Strachey rendered them in the past tense. I included the running heads that Freud used in the first German edition, which read as a sort of summary of his argument. There are only a few places where the old translation needed correction.

Freud’s theories have notably influenced surrealist artists like Salvador Dalí. Could you discuss how these theories specifically influenced Dalí and perhaps mention particular works that were directly inspired by Freud’s ideas on the unconscious?

Mark Solms: I think Dali almost literally illustrated Freudian themes. (I don’t think he was a great artist!) Freud, however, was impressed with his technical prowess as a painter. As for individual works: ‘The persistence of memory’ comes to mind immediately. Also ‘The great masturbator’ and ‘The metamorphosis of Narcissus’. The ‘Enigma of desire’, surely! Also ‘The melting watch’ and ‘The lobster telephone’. The list could go on and on…

How do you see the interplay between psychoanalytic theory and artistic expression

within the surrealist movement? Did Freud’s ideas provide a framework for artists to

explore dreamlike and fantastical scenes, and if so, how?

Mark Solms: As I have just said, I think some of them (the least interesting of them) merely depicted dreamscapes and explored Freudian themes in a fairly concrete and literal way. More interesting, in my view, was the use of Freud’s methods in automatic writing and drawing. Magritte, too, had a deeper and more intellectual appreciation of Freud than most of the surrealists did.

Looking forward, how do you envision the ongoing dialogue between Freud’s theories

and the art world? Are there emerging trends in art that you think will draw from the

newly clarified and revised works of Freud in the RSE?

Mark Solms: I think it is impossible to trace the influence of Freud upon contemporary art; it is just too ubiquitous! I hope that the RSE will make that influence more explicit once more, even if only for a moment. In my opinion, the most interesting artist working with Freudian ideas (in a deep and non-obvious way) is William Kentridge. But then again, I am biased of course!

The Revised Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud was commissioned by the Institute of Psychoanalysis, who chose Rowman & Littlefield as the publishing partner. Over the past 30 years, editor Mark Solms has undertaken this major work of comparative scholarship reviewing James Strachey’s English text against Freud’s German original.

The 24-volume set includes 56 new notes, essays, letters, and lectures and is available to purchase for £1,500/ $1,950.00. For more information visit: Rowman.com

©2024 Dr Mark Solms