It’s Tuesday the 28th of January 2020 and I’m joining Maddie Rose Hills in Copeland Park’s ‘Social’ for a G&T and a chat about art. Hills had got in touch the previous week to ask if we could have this chat. In addition to her own artistic practice, she regularly interviews other creatives. Hills has seen the benefit for her interviewees in discussing their own practice, an exercise which places the artist in a simultaneous maker-viewer role giving them fresh perspective on their work. Now it’s Hills’ turn.

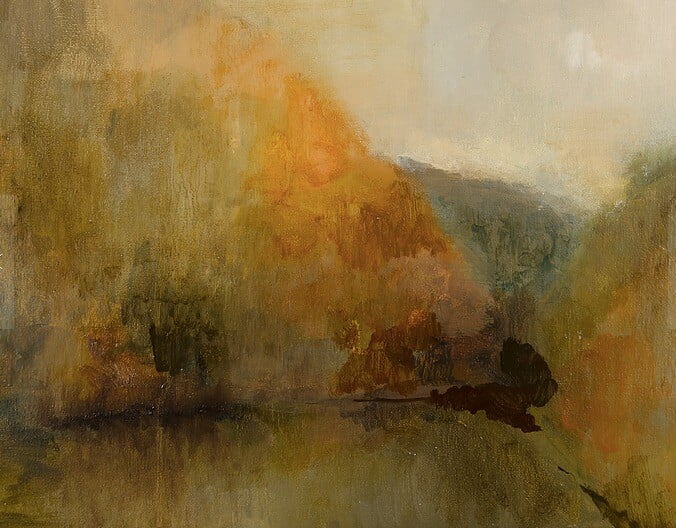

Since ’19 Hills has almost entirely stopped selling her works. A large amount of her time is spent on curatorial practice and on her work at Copeland Park, but the artist continues to paint a couple of times a week, focusing on landscapes from memory.

Hills’ landscape work marks a notable visual change in her portfolio. During her BA at Bristol and for a short time afterwards, Hills was creating large scale abstract work with the goal of documenting time through the multiple layers of paint which would be worked on for up to half a decade at a time.

‘Hues of Blue’ for ‘Where You Are Not’ – 2019

The move towards landscapes came about a year ago, beginning with representations from memory more literal than those she currently produces. The artist explains that she didn’t have much time “to think about what [she] was making or why”, and that building up the studies as if they were final works was a good practical exercise. For Hills, an artist with an early portfolio full of sensual, textural work, the act of memorising and recounting these memories in paint draws on a passion for expressing the tangible.

I’m meeting Hills at the end of her current SPROUT Residency. She tells me joyously about the overwhelming feeling she had visiting Wandsworth Community Scrap Project during the residency’s second week. The centre “promote[s] the reuse of reclaimable or lost resources for environmental and community benefit” (https://www.workandplayscrapstore.org.uk/about-us) and she tells me about the struggle to remain focused while searching for materials for her project there.

Her final creation involved (brass rubbing) on the walls of her wooden studio walls using pencils, graphite, and charcoal. Evidenced here is Hills’ devotion to texture, layer build-up, and the expenditure of time. “I have so much more of a connection to something I’ve made the longer that it’s taken” says Hills as we discuss the very physical processes involved in creating her work. Just like her abstract university works, the piece involves additions over time, and physical manoeuvring across a large space, and demonstrates the accretion of material and texture.

SPROUT Piece directly onto wall, 2019

We discuss the “importance of the underneath”. A return to “slow art” (as opposed to the speed and cleanliness seen in the production of contemporary ready-mades or work from Warhol’s Factory) is embraced by Hills through her ever-evolving pieces which she watches dry, the materials crack, and the canvas thicken. On the first day of the SPROUT Residency Maddie uploaded a photograph of the day’s work on her Instagram.

She was met with praising comment after comment and her mum told her not to touch the piece, it was perfect. Hills tells me how this potentially more “Instagrammable” work may be popular but that it “means nothing” to her. She can’t throw off the feeling that she “can’t put that out to the world as it is… it only took me a day”.

Hills’ work is Slow in a double sense: it requires the time for deep inspection from the viewer, as well as being a lengthy process to produce. Arden Reed in his 2017 book Slow Art: The Experience of Looking, Sacred Images to James Turrell describes his journey to defining Slow Art:

I collected works of visual art that compel rapt attention, or at least cultivate patience, works that lead us to look scrupulously, even indulgently, or works like Ad Reinhardt’s “black” paintings, that only reveal themselves over time.

Arden Reed

It is this coaxed out “revealing” which rings so true with Hills’ work. There is a growing significance being laid on the hand of the artist, a rebellion against commercial art produced quickly and slickly. Such a return to 19th Century values seems at odds with the birth of social media and digital gallery spaces. However, we seem to be witnessing a return to an ideology of artist as craftsman and patient viewing.

Although more people than ever are visiting art galleries, the average time spent viewing each work is currently around 18 seconds. Our viewing habits in a gallery mimic our infinite scrolling through social media: “Next!” Anyone who has been to an art gallery in the last decade will have seen visitors looking at the art through their phone camera.

The Slow Art Movement (and Slow Art Day celebrated in April) is beginning to penetrate the gallery space, with museums running drawing classes, yoga sessions, and playing music to calm down the quick-paced viewer and encourage closer, longer examination of art works.

Hills relationship to oils is like that of a sculptor to their raw material. Oil paint requires a similar “sculpting”, a slow drying material which requires physical shaping and steadying. Hills’ attitude is that as long as a piece is in the studio, it is not done. Her works are rarely “finished”, but in a state of display before further work is done. Hills’ father purchased a work from his daughter while in an unfinished state, unsure why Maddie protested. I’m reminded of an urban legend that Damien Hirst having sold a spot painting to a family member returned to it while hanging on the recipient’s wall to “correct” the colour of one spot. Discussing her work with Hills highlights the idea of artwork having an organic lifespan which you cut short by deeming the piece finished.

Hills has been attempting to let go of the pressure to produce quickly, and says that not trying to sell work helps. Having gone through a commercially successful period after university producing quickly “finished” abstracts, Hills is finding her current landscape phase a good vehicle for slowing down.

The style of her commercial period isn’t one by which Hills wants to be defined despite it being one she is justly proud of. Following a framework sold well but Hills describes feeling dutybound not to cave into the lure of commercial repetition at the cost of expanding creativity: “if I wanted to make money I wouldn’t be an artist”.

‘Yellow Cliffs’ 2019

We talk at depth about Instagram and the desire to curate. Hills has to accept that in order to stay creatively free, her Instagram is going to look “all over the place”. With no real set style to speak of, her uploaded images are eclectic and show real development, trial, and primary references. We agree that painting is having a “moment” online and we’ve noticed a boom in emerging figural painters.

Instagram is visually over-exposing by its very nature. We also agree that it’s not the best platform for explaining background. Hills’ work depends on a knowledge of its literal and chronological layers: the final piece created for her SPROUT Residency – a multi-layer painting of white oil paint – is entirely unsuited to digital display on Instagram. “Slow Art” may struggle to thrive on digital platforms alone. Slow Art requires the intimacy of live-viewing, as opposed to the pornography of digital imagery. To view slowly and feel deeply during physical encounters with visual art is at the foundation of the Slow Art Movement. To quote Reed:

Antidotes to our computer-screen worlds, these encounters anchor us in the here and now, in addition to laying down memories … Maybe in a secular age Slow Art can give us the kind of consolation that everyone is looking for.

Arden Reed

https://www.instagram.com/maddie.rose.hills/

©2020 Maddie Rose Hills