The Chinese-born, London- and Beijing-based artist strips words to sound and fragments history to reveal how language disciplines bodies and reshapes power.

A black rectangular panel bears a spare inscription: /tɜːn əˈraʊnd/. At first glance it looks like a scrap of phonetic notation from a dictionary.

Courtesy of Li Yu

This is part of Li Yu’s installation In Other Words (2023), which turned the whole gallery into a participatory exercise for its audiences. Built from video, sound, and sculpture, it casts viewers as “respondents,” subject to prompts that demanded decoding, listening, and even turning their bodies. The audience may find themselves at an advantage if they have a higher fluency in English, yet they also fall more easily into the traps of these commands.

That tension between familiarity and estrangement, polish and fracture, runs throughout her work.

Courtesy of Li Yu

Born in China and now working between London and Beijing, Yu has built a practice that spans sculpture, performance, poetry, and sound. What holds it together is her relentless probing of systems of language, politics, and institutions – questioning the margins of knowledge and culture while examining how value is assigned in art and life.

Courtesy of Li Yu

Making art for me is largely about observation

Li Yu

Training and Distance

Yu received training in traditional sculpture during her five years of study at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. This background shaped her to be extremely observant and attentive to detail, constantly drawing creative inspiration from her daily routine.

Courtesy of Li Yu

Later, in London, where she first studied and then worked, Yu began to see layers and contradictions she might not have noticed at home. In Britain, she often found herself on the edges of social life, where belonging was conditional. It was there she began to treat language itself as material.

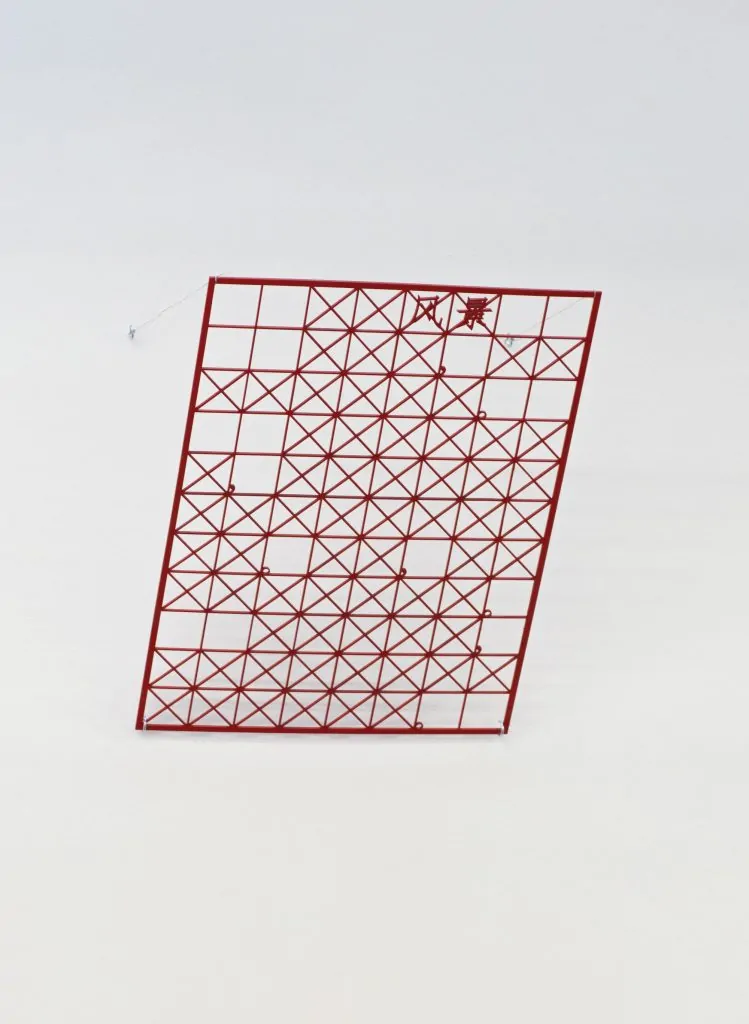

This shift shaped works like Listening Practice (2023), where a parrot repeats what it has been taught on a language-learning tape; Writing Practice (2022), where only the Chinese word for “scenery” (风景) remains on the page and the rest is left to be imagined by the audience; and In Other Words (2023), which pares “turn around” down to sound alone. All these works investigate how language disciplines behaviour, and how repetition and absence can expose that discipline.

Cassette player sound

Courtesy of Li Yu

Life on the Edge

Much of Yu’s practice is informed by theories rooted in feminism, which allow her to sense the power relations that remain beneath the surface of her daily encounters. Her recent sculptures reflect that unsettled position. Hands point, offer, or pass – yet the gestures never quite land. These suspended movements resist closure, suggesting a time held open, where everything still carries the potential to change.

Preservation as Resistance

In 2023, Yu and fellow artist Chaney Diao founded DUMP – an archive for works abandoned when artists could no longer afford storage. DUMP emerged as a response to the precarious reality of being an emerging artist in London, where many artworks end up disposed of not for lack of merit, but for lack of space. Through exhibitions and a 3D archive, DUMP catalogues, digitises, and re-presents these orphaned works.

Courtesy of Li Yu

For Yu, DUMP is both an artwork and an act of resistance. Its existence challenges the standards that decide what is worth preserving and what can be discarded. She hopes it will serve as a counter-record, capturing not only the artists who enter museums but also those left outside them.

Retooling History

Yu’s interest in power also looks backward. Recent projects retool Assyrian reliefs – monuments once carved as imperial propaganda, now displayed as colonial spoils in the British Museum. Long celebrated as “classics” in sculpture education, they are also enduring images of conquest.

She sees their language of domination as something that persists across histories. She pulls fragments into the present as commentary on how propaganda continues to circulate. As she puts it, her work does not dismantle or preserve history. It retools for today.

Courtesy of Li Yu

A Continuous Sentence

For Yu, the variety of mediums she works in does not dissolve her practice. They feel, she says, like parts of a single continuous sentence. Each individually they may appear as broken sentences: parrots repeating lessons; gestures halted mid-motion; words stripped into phonetic code. But they are all precisely threaded together through the return to questions of power, language, and survival.

Yu’s artworks ask the viewers to notice what institutions neglect, to sense the discomfort in everyday speech, and to value what has been discarded.

The philosopher Michel Foucault once observed: “People know what they do; frequently they know why they do what they do; but what they don’t know is what what they do does.” Yu’s art lives in that gap – between intention and effect, language and command – reminding us that even the smallest utterances and simplest gestures do more than we know.

It is in that blind spot, at the margin, that her work insists on beginning again.

©2025 Li Yu