“The Future is Now PT.II: Re/Form~ation” at CasildART Contemporary showcases seven vibrant Black British artists utilising various materials such as glass, wood, textiles, and tissue paper to create new worlds and narratives, pushing the boundaries of form and reshaping perspectives on Black experiences, art, and culture.

The featured artists Asiko, Christopher Day, Donald Baugh, Othello De Souza, Elaine Mullings, Maggie Scott and Theresa Weber explore themes of worldmaking and legacy.

CasildART Contemporary is a not-for-profit gallery dedicated to addressing the underrepresentation of Black artists in fine art institutions, commercial galleries, and museums. Founder Sukai Eccleston launched the gallery with a mission to be a catalyst for change and transform the visual landscape in the UK by inserting Black narratives into the culture.

I spoke with some of the featured artists, including Christopher Day, Donald Baugh, and Maggie Scott.

Credit Lee Sharrock

© Lee Sharrock

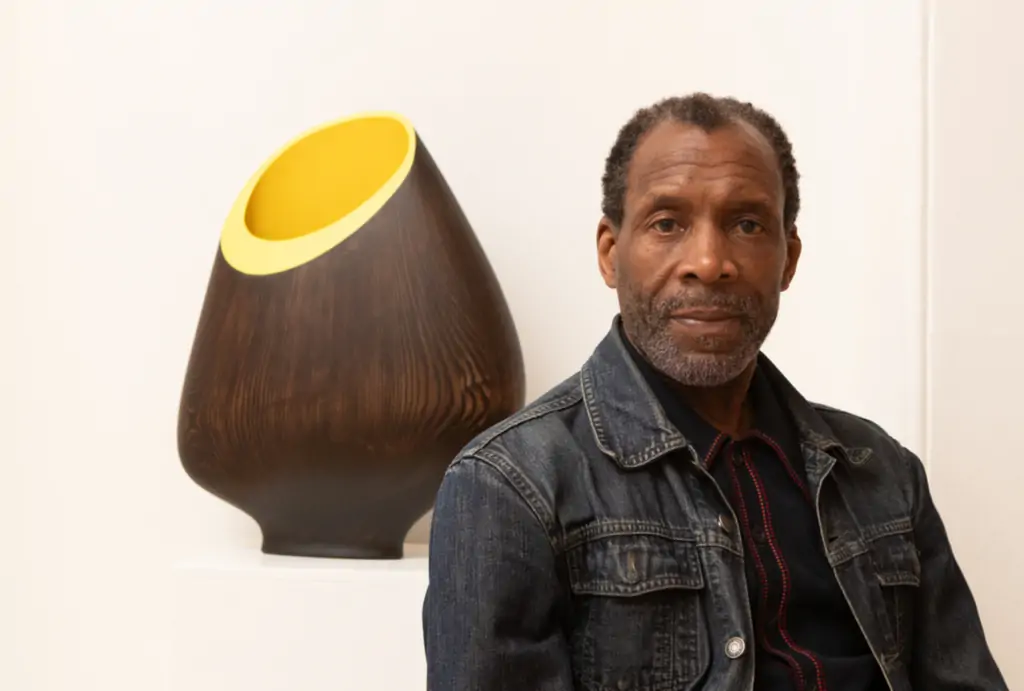

Christopher Day

Day creates highly personal works in glass and mixed media, and his intention is to discuss and investigate the treatment of black people in Britain and the USA, with much of his research focussing on the history of the slave trade in the Eighteenth Century and the events leading to up & during the Civil Rights Movement.

Combining materials used in both heating and electrical systems into his creations, Day finds he is able to create the perfect marriage of his artistic path and technical knowledge, both of which rely on dexterity and high levels of skill and craftsmanship. A reoccurring and signature theme are ‘copper cages’ which enclose his glass, representing the restriction of movement both physically and mentally that traders possessed over other human’s lives that were viewed simply as ‘commodities’.

Lee Sharrock: Why did you choose glass as an art form?

Christopher Day: To be honest, I didn’t choose glass, it chose me. When I started at University doing a BA course in glass and ceramics, I was studying slavery and civil rights, and looking into my own identity. The first time I blew into a piece of glass it wanted to escape from me because I didn’t have any control over it.

So it turned out that the medium of glass matched what I was studying – the fluidity of glass means that it wants to break free when you try to enclose it. So when I made these copper cages and I blew into them, the glass wanted to break free from the cages, so it was like a metaphor for the control of slavery. Being dyslexic, glass gave me a vocabulary and meant that I could visualise the concept of being incarcerated in a cage and trying to break free. Yeah, so the cage comes first.

It’s a bit like building a ship in a bottle – nobody knows how you get that ship in the bottle. I don’t come up with a drawing or anything, to create these cages I just manipulate the wire and the copper tube. Then, once I start to blow the glass I’ve got no control, and I think what I really love is that for the first time in my life I’ve got control. I’ve been controlled by society, controlled by identity, and being mixed-race, I don’t fit in, so the glass for me is a metaphor for trying to escape from that incarceration of somebody putting me into an identity that I don’t fit into.

Lee Sharrock: Can you talk about ‘Unconditional Love’, the sculpture you made for this exhibition?

Christopher Day: Yes, it references the transatlantic slave trade when children were taken away from their mothers and sold off into slavery. But the piece has layers and layers of meaning for me, and the title ‘Unconditional Love’ relates to my back story: I have a mixed-race Jamaican heritage and don’t know who my father is.

I was born in a society where mixed relationships were stigmatised, so that stigma of being mixed race has been with me all my life, but it’s only recently I’ve been able to talk about it. ‘Unconditional Love’ means that somebody should love you unconditionally no matter who you are or what background you come from. I never had that because my mum resented me, so ‘Unconditional Love’ is talking about that, but its main purpose is to talk about the trauma of African Mothers that were separated from their children when they were sold in auction, and never saw them again.

I wanted to tell that story with this piece. It’s hard to tell because it’s such a brutal story, and I tell the story with glass, which is such a beautiful material that used to decorate rich people’s tables in the 18th Century.

Credit Lewis Patrick Photography

© Lewis Patrick Photography

Maggie Scott

Scott graduated from St. Martin’s School of Art in 1976 with BA honours in Fashion Textiles, and set up her first studio in London in 1980. Scott creates art from the particularity of who she is: a black woman, a feminist, a daughter, a mother, an activist and a British textile artist. Her large-scale works draw on the aesthetic and symbolic potential of the process of felting.

The hand-felted re-interpretations of photographic images often explore the politics of representation and tensions and contradictions of a Black British identity. Photography and specifically portraiture has played a key role in all her work. While many of the manipulated images become textiles, each series of work always generates ‘stand-alone’ prints. Scott’s technical practice is unparalleled in the landscape of contemporary British art, sitting at the boundary of tapestry and digital media, she employs a combination of photography, digital collage and silk in a process known as Nuno felting. She achieved notoriety in 2013 for Zwarte Piet, a body of work exploring the eponymous Dutch phenomenon of ‘blacking up’. Using self-portraiture, she referenced the quaint and offensive Dutch ‘character’ by creating an alter ego for Piet.

Lee Sharrock: How did you get involved in the exhibition at CasildART Contemporary?

Maggie Scott: It was an invitation from Sukai. We were speaking a couple of years ago, and I was very preoccupied with a big show in Hastings. I live in Hastings and both Elaine (Mullings) and I we were involved In a large exhibition, and I had no space to do anything, so when she came to me for this show I was really pleased to be able to contribute.

Lee Sharrock: Can you talk a bit about your process and the materials you used for the artworks in this exhibition?

Maggie Scott: I used a technique called Nuno felting where you push fibres through silk, allowing me to print on the silk before I felt, and make the image I want on my computer. This piece references Zwarte Piet, the offensive Dutch phenomenon of ‘blacking up’ at Christmas. I created an alter ego for Zwarte Piet called ‘Big Sister‘. With ‘Big Sister‘ I’m inviting the viewer to re-evaluate Zwarte Piet as no longer a slave or child-like fool, but a commanding adult female present.

I’ve used Nuno felting for years, but now I’m moving into a different kind of technique after receiving some devastating news about my health, which was affected by exposure to textiles. So a new portrait in the exhibition is a self-portrait in response to the devastation I felt about not being able to work with textiles any more after 50 years. It’s from a series of personal portraits that are deeply personal because they are a response to this news about my health.

Credit Lewis Patrick Photography

© Lewis Patrick Photography

Donald Baugh

Baugh honed his craft at the world-renowned Rycotewood Furniture School in Oxfordshire Middlesex University and graduated in 1996. Since then he has exhibited extensively in London, Tokyo, Paris, Milan and Folkestone, building a solid international reputation with his passion for wood and creating elegant furniture for interiors and one-off carved vessels.

Baugh specialises in simple line and colour to create elegant solutions for lighting, furniture and his sculptural one-off vessels sourced from sustainable wood. Baugh is passionate about the sustainable practice of harvesting timber, working closely with the Forestry Commission and tree surgeon Dariusz Salarski to source his materials allowing each vessel a story to be told, celebrating the uniqueness of nature.

Lee Sharrock: How did you get involved in the exhibition at CasildART Contemporary?

Donald Baugh: I did a show last October and Sukai came to it and saw my work, and then she asked me to be in this exhibition when she opened the gallery. I want to do a show with Chris Day and Chris Bramley which is based on the passage of slaves from Africa to the Caribbean and the Americas. My work is not political, it’s about aesthetics. It’s about things I see in nature and my environment. I’m nomadic by nature. I’m a Forager.

Lee Sharrock: So are your pieces all found/ reclaimed pieces of wood, and can you talk about your process?

Donald Baugh: Some of it’s given to me by friends. The piece downstairs in this exhibition is from a friend’s walnut tree in her garden. Others I’ve in the workshop for 5 or 6 years. Some is from tree surgeons, and some from parks.

I haven’t had a TV since they changed from analogue! I got rid of it. It effects your work and your mind. I just design and make. I lost my father during covid, so it wasn’t a good time in that sense of personal suffering. But as a creative it was a good time because I could get up and go for a run, stretch, eat, then work from 11 or 12 until 6pm just putting down ideas, and the light was amazing.

My process is sketching on lining paper because the gauge is quite thick. Then I work out proportions and sizes and visualise how things will look in 3D. When you make a chair you make a thing called a rod, so you get the front, side and plan elevation all super imposed on each other in different colours. I use that process in my work and build a picture in my head roughly.

“The Future is Now PT.II: Re/Form~ation” is at CasildART Contemporary, 32 Connaught Street, Connaught Village, London W2 2AF until 7th September, 2024.

©2024 CasildART Contemporary