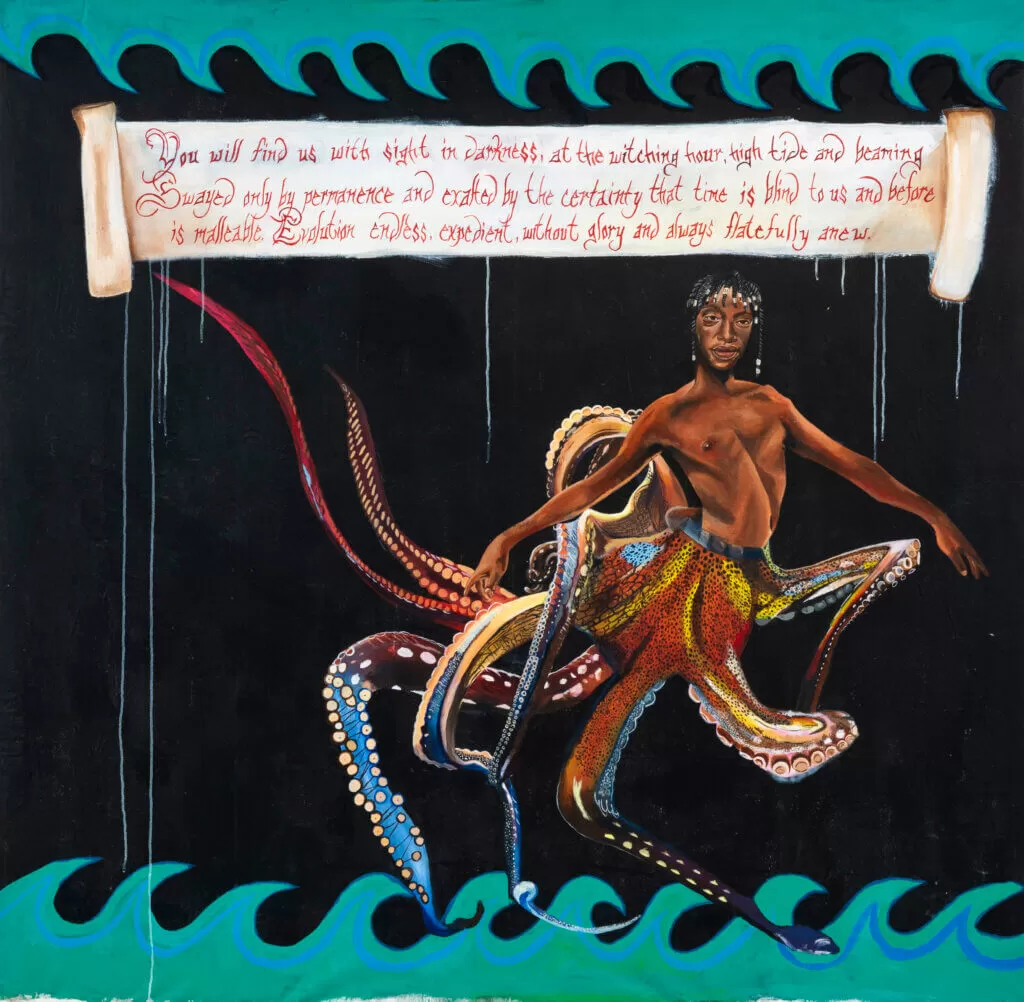

Khaleb Brooks is an artist whose work captures the black queer figure as an entity both perpetually out of place and firmly rooted in history. Brooks imagines new spaces for conversations around the Atlantic Slave Trade, jumping timelines from recorded history and making way for afro-futurist musings. Sometimes, Brooks’ work references African folklore, particularly in relation to water, creating therianthropic figures that exist within the contexts of lived black experiences.

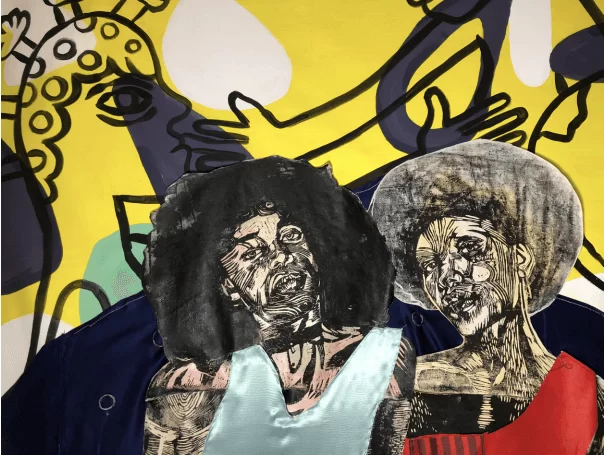

I think I’ll call it Morning (Detail, work in progress), 2019, Linocut, ink, fabric, acrylic on canvas

Slavery exists in our imaginary as something large, highly textured, painful and unspecific. It also exists in a realm of generational trauma that is so specific it must be ignored on a daily basis.

Khaleb Brooks

Depicted in paintings and collages, viewers see allusions to the Olookun legend, an Orisha spirit of Yoruba religion that resides in the ocean, to Yemaya, Goddess of the Ocean, to the flying African folktales. A freedom and fluidity remain constant in Brooks’ work, exemplified in the artist’s half human, half sea creatures. Both fantastical and wholly real, Brooks’ subjects consider how different identities can exist in spaces founded on their brutality, and how archived history and memory converge with mythmaking. Often, they are not folkloric, but rather conceptualized in a pre-colonial gender-variant society, dealing with externally prescribed monikers of representation and the implications of ancestry and generational trauma.

By including the black queer figure, which is myself, my friends, my community, I’m allowing us to take up space, where historically we have been written/painted out.

Khaleb Brooks

History is manipulation; it is often lip service that favours the victors, or rather, those who take what isn’t theirs to take. Brooks’ art is less about polarity and more about two or more interconnected ideas that coexist, related, if anything, by memory, archival evidence, media, and the manipulations therein. In a six-month research residency at the Liverpool Museum of Slavery, Brooks aims to connect the personal with the collective, further exploring ties between black people and water as relating to The Middle Passage and reconfigurations of artefacts from the long-nineteenth century. Some of Brooks’ findings include records of the first drag queen from that period: William Dorsey Swann, an enslaved person living in Maryland in the 1880s and 90s. Importantly, Swann was the first person in history to lead a queer resistance group and was known for advocating for LGBTQ rights, including the right to assemble.

Brooks’ own identities as a trans black man take centre stage through emotionally evocative performances dealing with the black trans body. Socialized as a black woman and existing at the intersections of myriad experiences and cultural frameworks—between countries and continents that share a colonial history mired in violence—Brooks uses the body as a way to work out the heaviness and exhaustion, but also the range of other emotional complexities inhabited by a liminal artist. Performance art confronts the peculiar convergence of an artist’s body with an audience’s discomfort, aptly presenting the perception of trans and black bodies in public—and private—life, a practice Brooks knows well.

In Gazelli Art House’s Curtain Twitching exhibition, shared experience and the public-facing questions and histories Brooks raises are turned inward. A showcase of artists appealing to the out-of-body experiences and reflections throughout the COVID-19 lockdown, Brooks includes pieces like Retribution: Sometimes I kick my own ass and What Chu Lookin at Ho? Before the Session, where sexual embodiment, conflicts with masculinity, and interpersonal tensions are put to the test.

In highlighting the otherness of black queer bodies and adding mythic layers to the complicated intersections found there, Brooks imagines a freedom in otherness, a space open to interpretation by the people living in it. Of course, the primary purpose of ‘othering’ an individual is to invoke a sense of restriction and, often, violence. After all, the otherness attributed to black bodies renders any black person as someone ‘out of frame’ or exceptional to a given ‘scene’. There is both a freedom and restriction in that otherness, for the marginalised is both mythologised and made new.

In Black Boys Can Swim, a film made in Lamu, Kenya, where locals live in relation to the water, Brooks subverts the stereotype, ‘black people can’t swim’. The statistics Brooks references are staggering: The Centre for Disease Control noted that African American children between 5 and 14 are three times more likely to drown compared to white children; in the UK, 95% of black British adults and 80% of black children do not swim. Rather than observing this phenomenon in a vacuum, Brooks encourages us to consider the diasporic traumas related to drowning, to the fact that slaves weren’t allowed to learn how to swim for fear of escape and that, during what we now label as the Jim Crow era, black people didn’t have access to swimming pools or swimming lessons, and that goes beyond typical images of segregated pools that come to mind. There is a long-standing tradition of barring black people from leisure activities, because of the implications of luxuriating bodies. Peace, fluidity, relaxation, whimsy—those ideas stand in stark opposition to labour.

Instead, the diaspora is burdened with images of an unforgiving sea, one that is murky, tumultuous, cruel. Black Boys Can Swim explores Brooks’ personal relationship with swimming and diving, and the otherworldly fascination found there, but it also documents the ease with which Lamu locals, and perhaps even Brooks, meld with the water’s flow.

Q: You have a background in Violent, Conflict and Development Studies. What inspired you to become an artist?

A: I’ve been making art for as long as I can remember—my grandmother was an artist. She used to take me to these big craft fairs in Chicago where she’d sell t-shirts with glittery fabric paint portraits on them. She always encouraged my work and imagination. Every few months we’d go to this craft store called Hobby Lobby and she’d let me stock up on art supplies, whatever I wanted.

By the time I was a teen I joined an artist apprenticeship programme in Chicago called Gallery 37. The programme was hard to get into so when I finally landed a spot, I was ecstatic. I did Gallery for about 4 years, drawing, painting, printmaking, video production.

I never thought I could pursue art full time, that’s just really uncommon in black families. Art is something you can explore for fun, not a career. It wasn’t until I interned at a gallery while working on my MSc that I was exposed to the art world. Once I went to Art Fair Paris, Frieze, 154…I was like ‘Okay, I can really do this!’

In a way my development background is one with my work, it’s an ongoing conversation about identity, conflict, social justice and blackness.

Q: Which mediums do you prefer to use in your practice? Are there any new mediums you’re interested in exploring?

A: All of them! Just kidding, kind of. I love oils, I’d say oil paints are my first love. They feel the most natural to work with. Due to how much I travel I’ve found acrylics incredibly practical though. It’s amazing to be able to paint something and boom it’s ready to go.

When I was painting in college, I used a lot of found materials, wood, windows, doors, curtains. I think a part of me is still attracted to those textures even though I can afford canvas now. I still find myself searching the ground for wire, rope, pieces of metal. Or saying, ‘Hey, what’s that sticking out of that bin?!’. I’m sure that also comes squat culture and spending a lot of time dumpster diving.

One of my latest favourite mediums is linoleum. I love how involved the process is, how physically laborious it can be with such a fine detailed outcome. I think the process of carving is now pushing me to explore sculpture. I’m excited to see how I can bring some of my painted characters to life in 3D.

Q: You reference the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, Yoruba religion and Afrofuturism in your work. How do you connect these diasporic motifs, and what inspired you to do so?

A: The Atlantic Slave Trade began appearing quite heavily in my practice in 2017. I was creating these portraits where I wanted to show beauty in blackness, I wanted to show us ‘having overcome’. But overcome what? I think for me an interrogation of the past, letting go of our current systems of thinking (i.e., abolition) is what will allow us to reimagine a future. How can a traumatic event like slavery exist in a space of collective healing?

Slavery exists in our imaginary as something large, highly textured, painful and unspecific. It also exists in a realm of generational trauma that is so specific it must be ignored on a daily basis. And if we are to engage with it, what aspects of ancestral identity can be used as a tool, form of power or reclamation of self?

I have photos of my family as sharecroppers on the Starksville, Mississippi plantation. I know my great, great, great grandmother Adeline Kennard was born a slave in 1858. I can trace my bloodline up to the early 19th century and name the slave masters that raped my ancestors. It’s personal for me; it’s personal for all of us.

I think these memories, feelings, archives, events, cultures are all fragments of a whole that, if pieced together, can create a greater understanding of who we are.

Q: How are these interests and ideas contextualised in your current project with the Liverpool Slavery Museum?

A: The International Slavery Museum in Liverpool has a wealth of information. I realised last year, during a residency at the Tate, that I needed to go deeper. Yes, I know what slavery is, what happened there and how it’s affected us. But what about individual narratives, how can the power of storytelling allow for us to engage with what’s happening now?

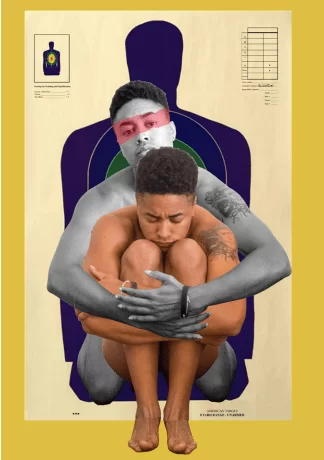

Duante Wright was just shot by the police during a traffic stop, he leaves behind a family, a child. How many black children have to grow up without fathers at the hands of the state? How has state violence against black people evolved until now? How many black trans people have died this year? While rights are being continuously taken away. Why don’t we know black trans history? We existed.

For example, William Dorsey Swann was the first ever known drag queen. He was born a slave in Maryland and is said to have coined the term “queen of drag” but most people haven’t heard of him. He spent his life in and out of jail for having drag shows and balls in the 1800’s. The 1800’s!

I’m currently exploring the logs and account ledgers of slave ships during The Middle Passage. I’m quite interested in connecting the archive and objects of these events to black/queer history.

Q: What is the difference between memory and history, and how do you characterize that difference in your body of work? How do you acknowledge the connection between those concepts?

A: I was listening to a Saidiya Hartman talk recently and she said, ‘History is fiction endorsed by state power’. History is linear, it involves a timeline usually written from the perspective of the oppressor, removed from memory, history is fixed. Memory is intangible, fluid, changes shapes, disrupts the senses, disappears and reappears, it’s alive. Memory is based on how something made you feel.

In a way I use history. I read about events, take notes of dates, spend time with photographs. But in my practice, everything becomes mixed up, whether with my body, a friend’s face, a location. Objects are taken out of their context and people become half sea creatures. They are in a dance with each other, history of course getting more recognition and memory not taken as seriously, but [is] much more important.

Q: How do ideas of freedom—in all senses of the word—and the black queer figure show up in your work? How do these figures ‘fit’ into these scenes?

A: I think black queer people existing is an act of resistance. Considering safety, access to healthcare, housing stability and job security are consistently threatened, creating spaces where one is free to be who they are is no easy feat. Being who you want to be, creating that life for yourself and showing the world you’re unstoppable—that is power, that is freedom. By including the black queer figure, which is myself, my friends, my community, I’m allowing us to take up space, where historically we have been written/painted out.

In the therianthropic figure series, the only way I could make the figures ‘fit’ into a conversation about slavery was to ‘take away’ their humanity. In slavery one was not seen as human, I don’t know how to ‘humanise’ the past. Maybe that’s not possible, but by reinterpreting being ‘non-human’ as almost deity like figures I hope that shifts the conversation.

Sometimes I feel like black queer people don’t really fit anywhere. There’s power there, existing in a space where you have no choice but to create something totally new. In the Session Series where I have these big linocuts with just a stark white background, I’m out of place. There’s really no where to situate that body. That man with bound tits, lady with a beard, that person exposing themselves.

Maybe not fitting is also freedom.

Q: How does your position as a liminal artist change within the larger socio-political context and history of the countries they are presented in?

A: Constantly. As my work is a reflection of my identity, experiences and collective memory my position changes often based on how I am personally read and (per/re)ceived. Blackness isn’t universal. And most are still unaware of black trans masculine experiences, even within queer communities. In the US I’m black, in the UK I’m perceived as mixed race due to my colouring; in South Africa I’m coloured and suddenly am a part of an entire history of Apartheid. In queer contexts I’m trans masculine, in many other contexts I’m just a black man, in my context I’m more nonbinary and really identify with my lived experience as a black woman.

I don’t think my position would be liminal in the US, or at least I hope that due to the expansion of the ‘black canon’, there’s now a context for me to exist in as a black American artist—we’re still working on the trans part.

Q: Most artists dealing with liminality talk of feelings of displacement; as a black trans man who has lived and worked in different countries, do you find remnants of displacement showing up in your work?

A: Yes, pulling from so many sources to make a work comes from having to be resourceful, scattered, and seeking to bring together all the different parts of myself together.

I think it also shows up in my interest in using different mediums. I find myself wanting to really jump in and indulge a certain project or method of working. This process is like finding a home in the work, a place to feel safe for a while, to set up shop, to get comfortable. And then, as always, it’s time to move again, and the movement itself is comforting, something I’m very used to, something that has to happen before I become restless.

Q: How did you develop your performance at Gazelli Art House? How do you usually develop your performance pieces?

A: Black Boys Can Swim was very impromptu. I was supposed to be on a flight back to England a few weeks ago and got stuck in Kenya due to lockdown restrictions. It’s one of the greatest mishaps the universe has offered me. The sea is something I consider in my work often, the depth of it, the mystery and the relationship the African diaspora has with it. It usually shows up in my work as solid black.

I’m currently on the coast of Kenya and am surrounded by water—literally, I’m on an island. Since being here, I’ve been completely immersed in how everyday live exists in relation to the sea. Whether it be people depending on fishing for their livelihoods, trade at the port, large groups of children swimming, local transport in boat taxis or the infamous dhows where hundreds of crews are sailing, it’s all about the water.

The stats show that most black people in England and America don’t swim. It’s becoming an epidemic as black children are 3 times more likely to drown than their white counterparts. So, I decided to create a work exploring those visuals and my own experiences with the water.

Performance for me is a very “in my feelings approach”. I go for whatever is overwhelming me at the time. My previous performance at Gazelli discussed the death of George Floyd and the one before that the deaths of black trans women. My own body is often cantered to acknowledge that the black body has been a site of trauma. I find the materialities of blackness particularly provoking when it comes to considering trauma happening due to the simple fact of blackness. With this in mind I find myself focusing on my nappy hair, or stripping, or using myself to slam paint into canvas. They develop from a place of black rage or joy, so far there hasn’t really been an in-between.

Q: Gazelli’s group exhibition Curtain Twitching prompts viewers to look at other perspectives after a year of confronting ourselves and our individual lives—how do your pieces touch on that idea?

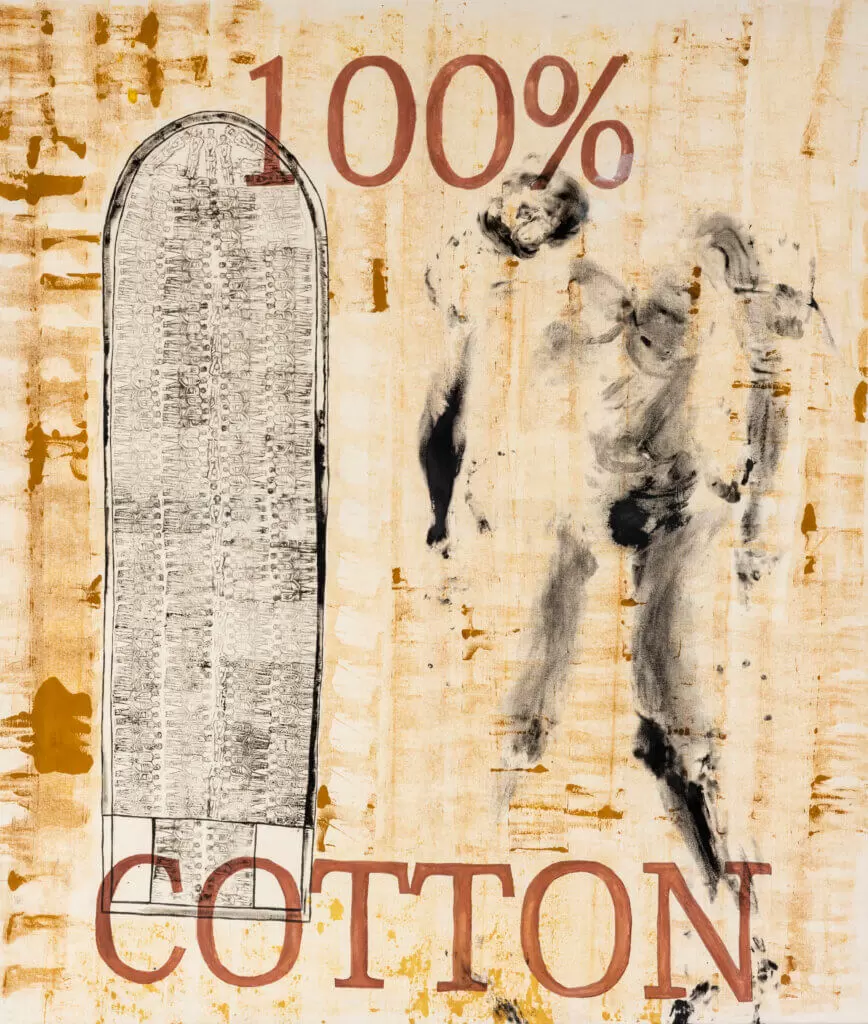

A: Most of the works on show were made during lockdown, What Chu Lookin at Ho? Before the Session, The Tides are Changing, “Retribution: Kicking my Own Ass and 100% Cotton is an earlier work. Each of these works in a way represent a different aspect/project of my practice. One offering insight into my relationship with my body, one representing my re-imagination of the slave trade and another dealing with conflict with my masculinity and identity. I really got stuck in my head at one point during lockdown. I’m sure we all did. I think you arrive at a place where you’re totally overwhelmed with yourself, your emotions and there is nowhere to place them. You can either go deeper in or you can try and distract yourself. But even when you distract yourself, you wind up back with you!

The Session Series pushed me to explore my relationship with sex and how my body was consumed during sexual experiences. As a trans person I’ve spent an unbelievable amount of time considering my body and being hyper aware of how I’m perceived. For the first time I had a moment to exist outside of constant scrutiny I had the pleasure of confronting just me.

It was over lockdown that I made the decision to get top surgery. I was like ‘Right, I can’t breathe and I’m suffering’. I had a complicated relationship with my body, I loved it, like really loved it! But I also had to change it to live a full life.

Another example of this is Retribution: Kicking my Own Ass. Both characters are me. I was having a terrible life altering conflict with someone who I was once close to. I feel like conflicts over lockdown hit different. They became warped and manic, hardened and settled in, feeling impossible to resolve and exacerbated. The conflict was incredibly gaslighting and for the first time I felt a deep guilt for being trans, for choosing masculinity for choosing not to be seen. I had to do a lot of deep diving to see myself, know myself and fall in love with myself again. Which, in the end, was totally worthwhile.

Grappling with these feelings and at the same time trying to keep my head above water, I found myself trying to whip myself into shape at any cost. I had to stop questioning my own authenticity, like right, you’re black, you’re trans; you’re proud. That’s that.

Follow Khaleb Brooks’ work via @khalebbrooks on Instagram and on www.khalebbrooks.com

See the online viewing room of Curtain Twitching, also on view for Londoners at Gazelli Art House through 24th April.

https://www.instagram.com/khalebbrooks/

©2021 Khaleb Brooks