With Bold Humour and Bare Emotion, Eric Stefanski’s Text-Driven Canvases Turn Private Struggles into Universally Shared Art

I had the pleasure of speaking with Chicago-based artist Eric Stefanski, whose bold, confessional work resonates deeply with audiences both inside galleries and across the digital world. His raw, often humorous phrases—scrawled across gestural canvases—have become widely shared artifacts of emotional honesty, earning him a devoted following far beyond the traditional art crowd.

At the core of Stefanski’s process is a commitment to stripping language down to its emotional essence—a practice rooted in daily writing and relentless self-reflection. Whether touching on grief, masculinity, or artistic doubt, his work invites viewers into moments that are simultaneously personal and universal.

Courtesy of the artist

In our conversation, Stefanski spoke about his evolving relationship with vulnerability, and the democratisation of visual art through social media. “You just have to edit through the noise to find something honest,” he told me. “But it’s there.”

Hi Eric, great to have you here! To start, would you mind telling us a bit about yourself and your practice for those who might not be familiar with your work yet?

Eric Stefanski: I’m originally from Chicago. That’s where I currently live and work. My wife and I lived on the East Coast for a while, where I went to graduate school. I primarily made sculptures for a couple years, but even then, if there’s been one consistent thread throughout the entire time I’ve been making work, it’s that text has always been the main driver.

Even when I was purposely trying not to use language in the sculptures, it always found its way in there in one way or another. That’s been the consistent thread. Language is the main driving motivator throughout all of it. That’s the North Star in the paintings or any other mediums that I’m working with.

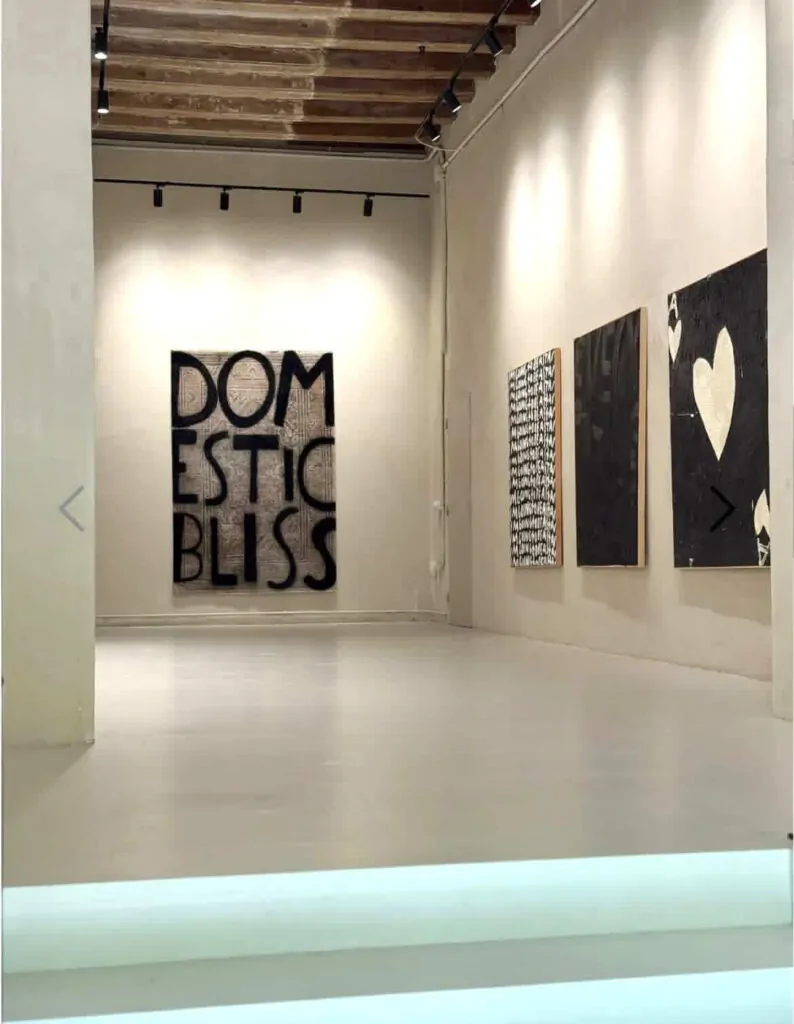

Escat Gallery Barcelona Esp. 2025

Courtesy of the artist

Can you share a little about your process with language? How do you arrive at those punchy, poignant phrases?

Eric Stefanski: Writing is such an important component in all my practice. I’m constantly writing. There are notes everywhere—here in the studio, in my office, on my phone, pieces of paper I find in my pockets. I’m always doing that. I’m always trying to pare the language down to its very core. Just edit the idea to as few words as humanly possible so you can get to the actual core of what the sentiment is. I’m trying to get to the most honest version of that language humanly possible.

What’s the latest work you’ve produced, and how do you approach balancing language with vulnerability?

Eric Stefanski: This morning, I did a painting. My wife and I recently suffered two miscarriages, and that was what the painting was about. Instead of writing how I felt about it or what I went through, I just used the date. That was the motivator. Just find the core of what you’re feeling.

Today I’ve been inundated with messages from people saying, “I experienced that,” or “my wife experienced that.” And that becomes really relatable. That’s when it’s operating strongly—when it’s both didactic and polemic. It’s referencing art history and pointing inward to raw emotion. That duality is really important.

Courtesy of the artist

Do you feel a responsibility, as an artist, to be vulnerable—to make work that comforts and connects?

Eric Stefanski: I think all artists, regardless of the medium—whether it’s music or film—have a responsibility to be vulnerable.

The more vulnerable we are, the more honest we are in our intent to make the work. The more specific we make it to ourselves, that is when your audience is going to respond. Making it that vulnerable and that specific is a way for people to come into the work and enjoy it.

Courtesy of the artist

Does making work help you process emotions? Do you find it therapeutic in some way?

Eric Stefanski:I really hope I’m not using the work for therapeutic reasons. I’m not in my studio cutting off my hair like Van Gogh. But of course, that has to be a part of it because of how much I do it—I make artwork every single day. And when I’m not doing it, I don’t feel good. I’m frustrated. I feel anxious. I’m always thinking about it. So, I kind of have to do it.

I feel better when it’s done. There has to be a therapeutic motion to it because it gives you self-worth: “I created that. That exists in the world now because I did it.” That is the most rewarding feeling you could ever imagine. Better than any drug I’ve ever taken.

I spent ten years working in cold basements, unheated garages, freezing warehouses—I was flat broke. But I had to make the work. Every day. I still do. It’s not about the money. There are easier ways to make money. I have to do it. I don’t feel right if I don’t. That’s just what it is.

Courtesy of the artist

Your work often feels ironic, even humorous—how do you balance that with your raw confessions?

Eric Stefanski: I think humour is an initial way for people to get into the work. It’s a really quick way to show intelligence. Once you have them, you can start another narrative. Also, painting has this really long, weighty history filled with tragedy. You can undercut the seriousness of it with humour. You can make fun of it.

I’m self-aware enough to know what I look like. I like motorcycles, whisky, lifting weights—so I use the colour pink. I use self-deprecation to undercut my own ego, that masculinity. I’m making these large, gestural paintings that come from a history of complicated, middle-aged men. So, I use humour to take out my knees from under me—to show I’m actually way more vulnerable. And I love that.

Are there any artists you look up to who have inspired your practice?

Eric Stefanski: One of my favourite artists is the Japanese conceptual artist On Kawara. I love the idea of documenting time. I think sometimes we forget that’s such a major component to the work.

Even if we’re painting a still life of apples or Kim Kardashian, that process is recorded. I look at my paintings like that too. I open my Instagram, and every day—or every other day—I’m making an artwork and posting it. It’s a snapshot. It brings me back to that day, that emotion. Whether I was depressed or happy or whatever—it’s recorded in that object. That matters.

Courtesy of the artist

As an art historian yourself, how do you feel about your work circulating outside of the gallery—becoming memes, tattoos, screenshots? I’ve actually saved a few to send to friends myself.

Eric Stefanski: I love it. People send me tattoos of the work. I think whenever there’s a movement in art, someone always says, “That’s not art,” or “my kid could do that.” And they’re always wrong. It should feel a little uneasy when you’re looking at it.

People look at art through screens now. You can argue whether that’s good or bad, but I can lie in bed and scroll through 100 artists I’ve never seen before. That’s incredible. Our accessibility to work is stronger than ever. You just have to edit through the noise to find something honest. But it’s there.

This is the first generation of artists who can post a painting, and thousands of people can see it. That’s a good thing. And for younger artists, that accessibility can sustain their practice. That’s powerful. It’s a kind of democratisation. And I don’t know what it’s going to look like in 20 years, but I do know that having more access to people’s work is a good thing.

Eric Stefanski’s work continues to captivate audiences worldwide. In 2024, he presented I’m Trying to Live Forever at Lowell Ryan Projects in Los Angeles, offering a fresh perspective on his introspective themes.

The same year, I’m a Genius, I’m a Fraud was showcased at Harper’s Gallery in East Hampton, NY, further solidifying his presence in the contemporary art scene. Most recently, Stefanski has unveiled I’m Never Saying Goodbye at Escat Gallery in Barcelona in May 2025, promising to deliver his signature blend of raw emotion and wit to an international audience.

©2025 Eric Stefanski