Through Faith and Memory, emerging artist Jemila Isa Unfolds the Subtle Resistances of Womanhood

In the work of Jemila Isa, the pull between faith and doubt, between past and present, unfolds in scenes shaped by her upbringing in London and her Nigerian heritage. Her paintings and sculptures carry the quiet weight of memory—echoes of Pentecostal hymns and the ever-watchful presence of chapel walls.

Her practice reveals a restless inquiry: into the power structures woven through womanhood, into the invisible negotiations demanded by faith communities, into the quiet radicalism of looking, questioning, and remembering.

Photo: Brynley Odu Davies.

Courtesy of the Artist and Bolanle Contemporary

The idea of dual identity is something I often reflect on—not just in my work, but in my personal life as well. I frequently wonder how different I might be—how differently I might see the world

Jemila Isa

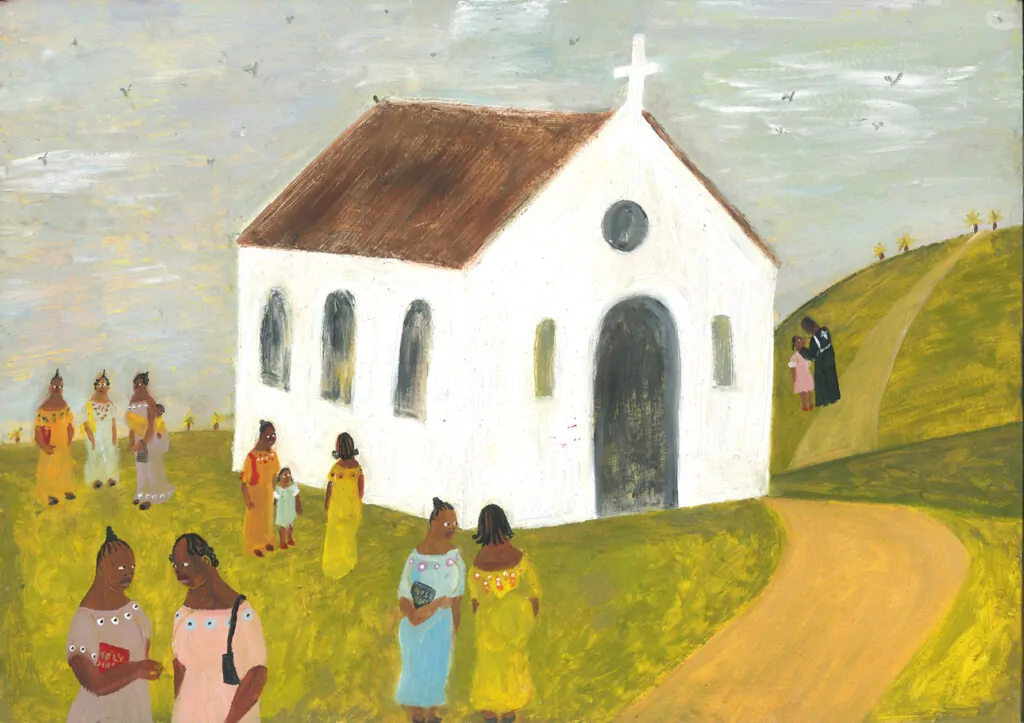

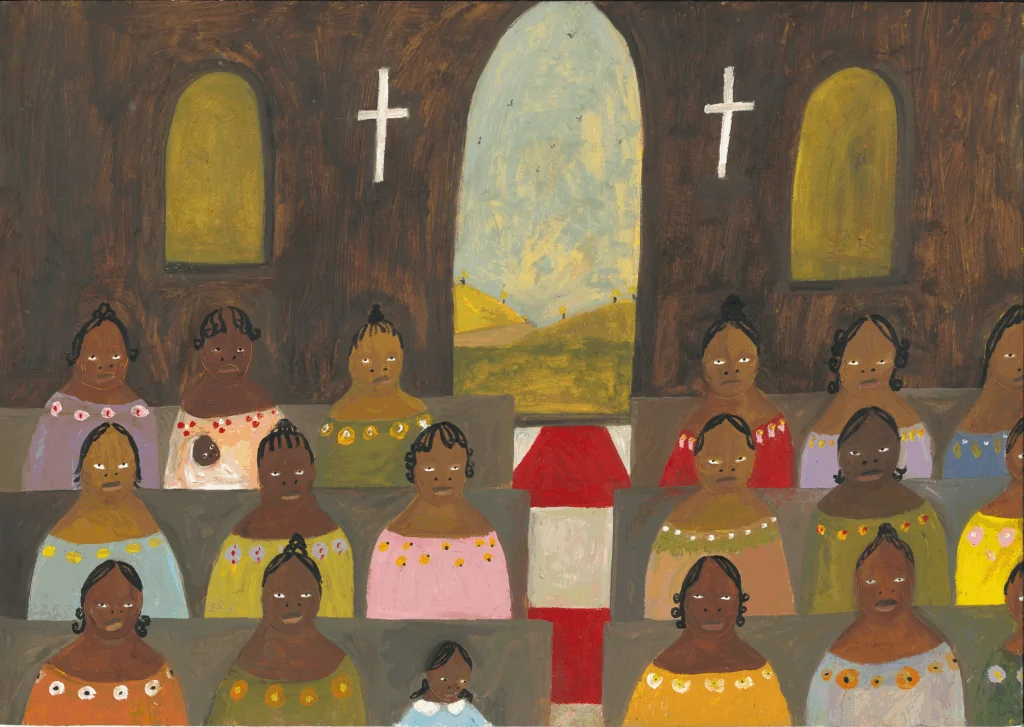

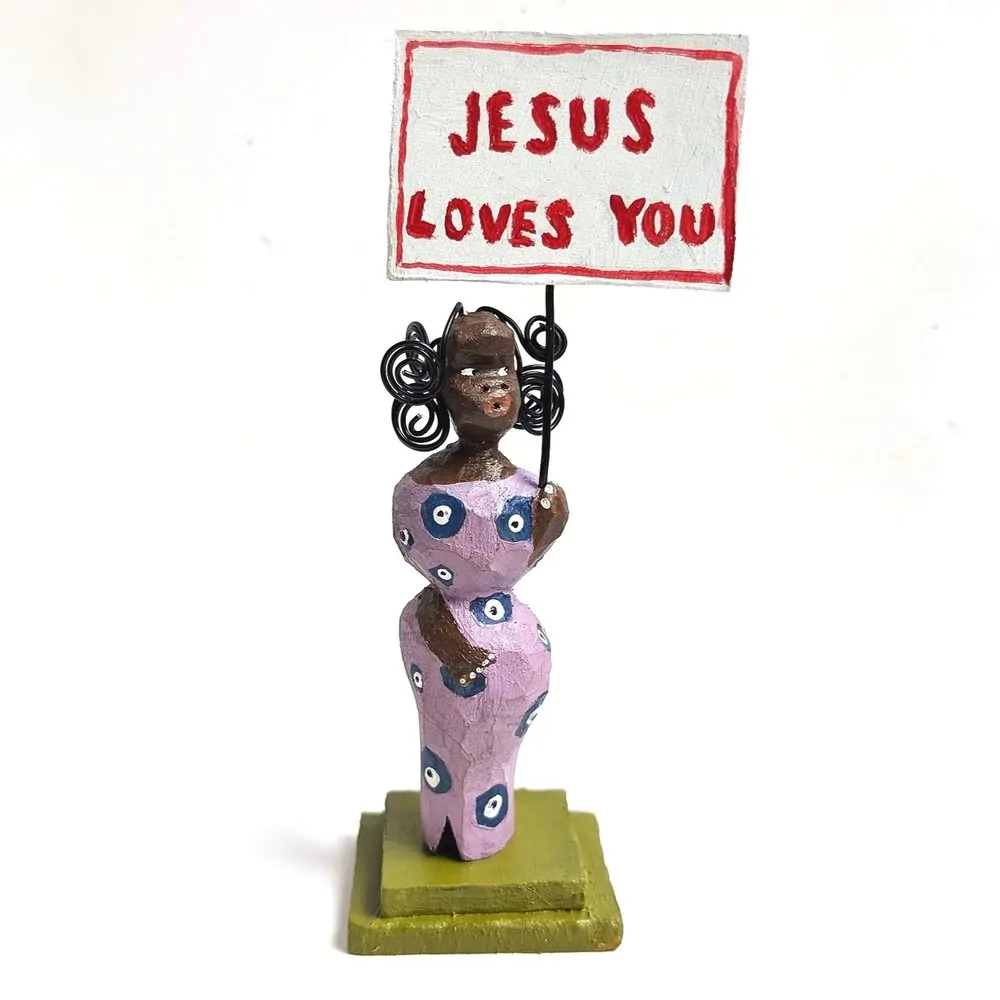

Isa’s paintings and sculptures do not demand allegiance or rejection. Instead, they sit — quietly — in the ambiguous spaces between reverence and resistance, oozing the folk aesthetic of some of the greats of modern art. Yet Isa assembles a vocabulary that is at once ancestral and distinctly her own. Her recurring figures — street preachers with Bibles raised skyward, choirgirls on the cusp of disillusionment — embody both the vulnerability and the authority of belief systems that have shaped diasporic lives across generations.

In the artist’s White Chapel series, one of my favourite pieces is Congregation (2025). In this evocative painting, Isa draws us into a scene of collective reverence and warmth, capturing a timeless moment within a small, close-knit church congregation — a sanctuary defined by arched windows, twin white crosses, and an open doorway that yields to a pastoral landscape, as if heaven and earth quietly touch just beyond the chapel walls. The setting is sparse, yet full of meaning.

The work bears the unmistakable marks of narrative primitivism — flat planes, frontal figures, and a restrained yet expressive palette. Folk art at its finest.

Last month, Isa, alongside Eilen Itzel Mena, featured in the duo exhibition In Her Spirit, curated by Bolanle Contemporary at Sadie Coles HQ. Here, Isa’s careful containment of form meets Mena’s expansive chaos, mapping a transatlantic spectrum of Black spiritual experience: the tension between dogma and intuition, between survival and transcendence.

There is a humility in Isa’s refusal to insist on a singular reading of her work. For her devout mother, the paintings might offer a balm; for others, they provoke quiet unrest. Yet beneath every surface lies the same elemental force: the insistence on being seen fully, beyond stereotype, beyond category.

If Isa’s paintings could speak, they would not lecture or sermonise. They would ask only that we sit — with care, with patience — and listen to the stories murmuring just beneath the brushstrokes.

We spoke with the emerging artist to learn more about her practice, inspiration, and more.

You were born and raised in London, yet your work is deeply informed by your West African heritage. How have those dual influences shaped your understanding of Black womanhood—and how do they manifest in the visual language of your work?

Jemila Isa: The idea of dual identity is something I often reflect on—not just in my work, but in my personal life as well. I frequently wonder how different I might be—how differently I might see the world—if I had been born and raised in Nigeria rather than the UK. It wasn’t until adulthood that I began to understand just how disorienting and disruptive it has been to shape my identity in an environment that I am not native to, and within a society that, more often than not, harbours negative connotations about people like me.

Oil on Paper (29.7 cm x 42cm)

Courtesy of the Artist and Bolanle Contemporary

Religion, particularly the African Pentecostal church, plays a powerful and recurring role in your imagery. When did you first begin to see the church not just as a personal or communal space, but as a lens through which to explore gender, power, and cultural identity?

Jemila Isa: For as long as I can remember, my mum was involved in some form of Christian

denomination, which meant that my siblings and I attended church every Sunday. The exact dates are a little hazy now, but between the ages of about 11 and 14, I was also part of the church choir. By the time I turned 16 and began carving out more independence for myself, I stopped going regularly—and it’s now been well over a decade since I last attended church. Even though I was always somewhat sceptical of the motivations and teachings of the churches I

grew up in, they were such a significant part of my upbringing that it’s almost inevitable they would find their way into my work in one form or another.

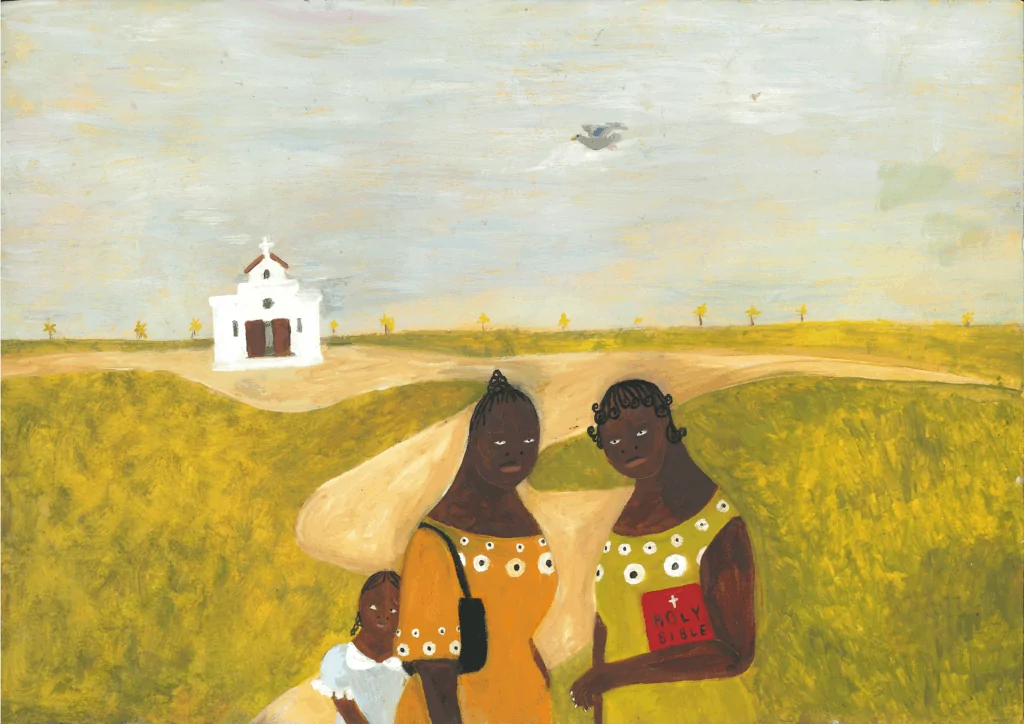

You often return to the image of two women in conversation, with a young girl nearby and a white chapel looming in the background. What made you continue to revisit that motif—and how has its meaning evolved for you over time?

Jemila Isa: The young girl in the paintings symbolises both my own scepticism—and that of

many others—towards the church. In contrast, the two adult women are depicted either deep in conversation or looking away from the chapel, seemingly unaware of their surroundings. This contrast reflects how, as some might argue, many African women follow the Christian faith unquestioningly, often without engaging critically with its teachings or origins.

The white chapel seems to operate as both a spiritual centre and a symbol of societal surveillance. How do you see the architecture of the church functioning as an emotional and ideological force in your work?

Jemila Isa: The church is often referred to by many Christians as ‘the body of Christ,’ though incorrect- growing up I interpreted that to mean that the actual church building is the body of christ. but I believe that, in many ways, it has also functioned—and continues to function—as a form of surveillance, particularly over women. It plays a role in reinforcing certain behaviours and expectations, ensuring that female followers remain within prescribed boundaries.

oil on paper, 29.7 x 42cm, 2025

Courtesy of the Artist and Bolanle Contemporary

Your work sits at the intersection of spirituality, tradition, and control. What kind of conversations are you hoping to open up about the expectations placed on African women within religious communities—both in the UK and across the diaspora?

Jemila Isa: I want to create a space where women feel free to question their faith—to reflect on how they engage with it, and whether it empowers or oppresses them within the context of their individual lives. I don’t believe there’s a definitive right or wrong answer, but ideally, we should be making choices that truly serve and support us.

Much of your work seems to occupy a space between reverence and critique. How do you hold that tension—especially when dealing with institutions that are culturally significant but also limiting?

Jemila Isa: I think that within a gallery setting—particularly among audiences who regularly engage with art—the tension between reverence and critique is quite apparent. However, when someone like my mum views the work—a devout Christian woman who rarely, if ever, questions her faith—she interprets it through a very different lens. For her, the work appears wholly reverent, a celebration of Christianity, and that brings her joy. I don’t feel the need to correct her. On the other hand, women who also grew up in the church but have taken a more introspective or questioning path tend to immediately pick up on the subtle, ominous cues threaded throughout the work. They recognise the complexity—the quiet resistance—that exists beneath the surface.

Photo: Arthur Gray | Courtesy of the Artists and Bolanle Contemporary.

You work across painting, sculpture, and animation. How do you choose the right medium for a particular narrative or idea? Are there certain stories that can only be told in one form?

Jemila Isa: After experimenting with different materials for a while, I eventually decided on

a structure that felt both practical and intuitive for me: all of my paintings would be made using oil paints, my sculptures painted with acrylic, and my animations created using watercolour. This approach brought a sense of cohesion and ease to my practice, allowing the process to flow more naturally.

When it comes to choosing the right medium for a particular narrative, I always begin with painting. If I feel there’s still more to express—something the paintings alone can’t fully capture—I then introduce animation or sculpture. These additional forms allow me to extend the conversation, to say what the canvas couldn’t quite hold on its own.

50cm x 15cm, 2025

Courtesy of the Artist and Bolanle Contemporary

Your sculptural figures of African street preachers—Bible and megaphone in hand—are so evocative. What drew you to them, and how did you approach capturing their authority, vulnerability, and presence in a threedimensional space?

Jemila Isa: I’ve always been intrigued by these women, wondering what events in their lives

might have led them to the point where they stand on street corners, hurling Bible verses at random passersby. I felt compelled to incorporate them into my work, as they resonate deeply with the themes I explore. The sculptures seemed like the most fitting medium to represent them, as much like a sculpture, the women themselves, have become fixtures on busy city street

corners.

The street preacher often provokes a mix of reverence, confusion, and even resistance. How do you think about the ambiguity your work might generate for audiences unfamiliar with the deeper cultural and religious contexts you’re drawing from?

Jemila Isa: Without a deeper cultural context, my work could easily be interpreted as a

reverence for the church, or perhaps as an art ministry similar to that of the artist/preacher- Sister Gertrude Morgan. While that’s not my intention, I’m at peace with it being read in that way.

Your pieces carry a quiet, contemplative energy—but the spaces you depict are often loud and full of life. How do you think about balancing the internal and external rhythms of Black religious experience in your work?

Jemila Isa: I don’t often dwell on it, as navigating the internal and external rhythms of the

Black female religious experience is something I’ve done my entire life. For better or worse, this duality is a core part of who I am, and it naturally manifests in my work.

Your current exhibition, In Her Spirit, at Bolanle Contemporary—presented in dialogue with Eilen Itzel Mena—creates a space where transatlantic Black womanhood is both honoured and interrogated. What kinds of conversations or creative tensions emerged through that collaboration? And what did you hope to offer, or challenge, in the way African and Afro-

Diasporic audiences see themselves reflected in the work?

Jemila Isa: Itzel’s practice revolves around African spirituality and mysticism—for example, Eilen is a practitioner of Ifá, an indigenous West African religion. My work for the show, by contrast, focused more on religion, specifically Christianity. However, within the context of African Pentecostal churches, there is a significant overlap between Christianity and traditional African spirituality.

To me, this felt like a conversation between chaos and order—organised religion versus untamed spirituality. This dynamic is also reflected visually in our styles: Itzel’s large, expansive, beautifully chaotic abstracts contrast with my smaller, framed, and more contained figurative paintings.

Photo: Haiyi Wang

Courtesy of the Artist and Bolanle Contemporary

You’ve received meaningful support from institutions like Arts Council England and Black Blossoms Studio. How has that recognition shaped your path—and how do you think about legacy, particularly when it comes to supporting or mentoring the next generation of Black women artists?

Jemila Isa: Support from these institutions has, and continues to be, a decisive factor in

whether I can pursue a career as an artist or if I must step away and choose another path. It’s that significant—not just for me, but for Black women artists as a whole.

Courtesy of the Artist and Bolanle Contemporary

If your paintings could speak, what do you imagine they would say to the viewer? What truths—or questions—are they asking us to sit with?

Jemila Isa: If my paintings could speak, they would say they long to be seen—not merely

observed, but truly understood.

Finally, how would you describe your philosophy of art—not just as a creative practice, but as a way of living?

Jemila Isa: To answer this question, I’d like to share an excerpt from a journal entry I wrote

over 10 years ago, on November 17th, 2014:

“Getting back into the rhythm of creating art, I realise it’s when I’m happiest and most connected to myself. It’s the one thing that gives me hope. Without it, I would feel completely alone and afraid in this world. It continues to save me and keep me safe, and I will honour it by devoting my time to it.”

©2025 Jemila Isa