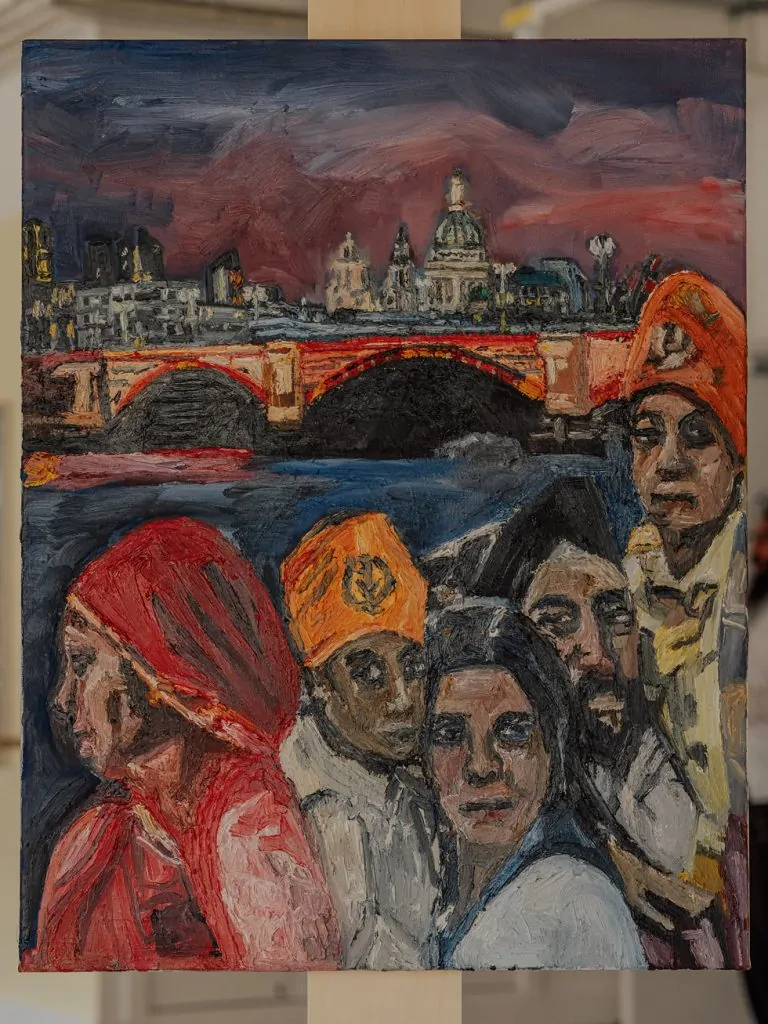

The British South Asian painter Jasmir Creed maps the psychic landscapes of modern urban life, where strangers collide, women negotiate visibility, and fleeting intimacies emerge amid alienation

By turns luminous and shadowed, Jasmir Creed’s canvases trace the psychic contours of the modern city. Her women are often caught mid-transit — in the rush of the Underground, in the churn of Trafalgar Square — at once absorbed into the crowd and quietly apart from it. “Observing strangers, I often feel both connected and disconnected,” she notes, a tension that runs like an undertow through her practice.

Creed calls the city a “forest-like ecosystem”, a place where danger and shelter intertwine. Her women — often South Asian figures adrift in public squares, train stations or labyrinthine malls — move between belonging and estrangement. It is this in-between state, visible yet vulnerable, that her canvases insist we see.

Photo by Taran Wilkhu

Courtesy WITHOUT shape WITHOUT form

That tension between alienation and belonging runs through my work: crowds moving in mechanical rhythms, individuals lost in thought, and fleeting moments of intimacy within the anonymity of the city.

Jasmir Creed

Her exhibitions mark shifting coordinates on this enquiry. Dystopolis (Liverpool, 2018) revealed the city as a dark labyrinth of alienation, while Utopolis (Warrington, 2023) searched for glimmers of belonging — light, plants, fleeting moments of connection — within the same urban structures. Neither is an endpoint; both, Creed insists, are part of an evolving enquiry into how cities hold us — and how they fail us.

That enquiry also carries a gendered weight. Creed connects her figures to the lineage of the flâneuse — the female wanderer in public space, visible yet vulnerable. Her women, often South Asian, drift between visibility and invisibility, amplifying overlooked presences while staging the instability of being seen at all.

Colour, too, registers these psychic states: warm yellows suggest intimacy, cold blues distance. Textiles — saris, bangles, the shimmer of South Asian fabrics — fold into the palette, colliding with the stark anonymity of urban architecture.

Beyond the canvas, Creed also works as a cultural organiser. She has curated projects such as InterWorlds: Transcultural Hybridity in Art (Slade, ongoing since 2021) and Many Stories (Midlands Art Centre, 2027), which will gather 15 British South Asian women painters. “Painting is at the core of my practice,” she says, “but curating is another way of shaping dialogue and pushing for visibility.”

Institutions have begun to frame her work within narratives of history and nationhood — the Imperial War Museum North recently acquired her paintings. Yet Creed is wary: British South Asian women artists, she argues, are too often confined to “identity politics”. She resists this pigeonhole, insisting on art’s wider reach: “Making work about fractured identity is important, but so is claiming the freedom to speak to human experience.”

For Creed, being an artist is less about possession than openness. “It means being curious and receptive to the world,” she reflects. Each brushstroke, each colour, becomes an act of architecture — constructing not only a painted space, but also mapping the luminous, dislocated terrain of contemporary life.

Jasmir Creed: Urban Spectrum is at Cedric Bardawil in London until 4 October 2025; Reflections – Sangat and the Self is at without SHAPE without FORM in Sloughuntil 2 May 2026

Your paintings often depict South Asian women in transit or solitude within train

stations, public squares, and crowds. What draws you back to these spaces, and what do they allow you to express about alienation and belonging?

Jasmir Creed: I’m drawn to urban sites like Trafalgar Square or the London Underground as places where monuments, crowds and routines of daily life coexist. Observing anonymous passengers and strangers, I often feel both connected and apart, creating fictional narratives about the people I encounter. That tension between alienation and belonging runs through my work: crowds moving in mechanical rhythms, individuals lost in thought, and fleeting moments of intimacy within the anonymity of the city. My paintings become psychogeographical terrains that map these dislocated scenes through paint and ink.

photo by Taran Wilkhu,

Courtesy WITHOUT SHAPE WITHOUT FORM

You describe the city as a “forest-like ecosystem.” Can you unpack this metaphor—

how do you navigate the tension between the city as a place of shelter and as a site of potential danger?

Jasmir Creed: Cities are layered like ecosystems, full of overlap and intrusion. They can feel protective yet unsettling – shopping centres, tube stations, or even patches of unexpected greenery can be both comforting and disorienting. Through painting, I remake these experiences into new visual terrains, translating unease through colour and form.

In Dystopolis (2018, Liverpool) the city appeared as a dark, alienating labyrinth, while Utopolis (2023, Warrington) gestured toward the possibility of belonging. Do you see these exhibitions as counterpoints, or as stages in an evolving inquiry?

Jasmir Creed: They’re part of an evolving enquiry. Dystopolis explored unsettling, domineering architecture that created a personal dystopia within the metropolis. Utopolis continued that line of thought, but also looked at how utopian elements — plants, light, moments of connection — might coexist with the alienating structures of modern cities.

Courtesy WITHOUT shape WITHOUT form

When viewers read your work through the lens of women’s safety in public space, do you see that as central to your intention, or more as an interpretive layer audiences bring to the work?

Jasmir Creed: It’s very much present in the work. Women in public space often carry a sense of being “other” -visible, yet vulnerable. I connect with the idea of the flâneuse (the female equivalent of the male strollers of 19th century Paris who blended with the crowds while observing others) reclaiming a role historically shaped by male privilege. My paintings reflect that perspective, showing women navigating urban environments that are both liberating and precarious.

without SHAPE without FORM frames Reflections – Sangat and the Self through Sikh philosophical ideas of self-discovery and kinship. How do those ideas intersect—or clash—with your explorations of fractured identity and urban alienation?

Jasmir Creed: That exhibition centred on healing and self-discovery. Making art is both challenging and restorative. It helps me process loneliness and alienation but also opens possibilities for collective connection when others see themselves in the work. For those navigating fractured identities between cultures, that sense of recognition can be powerful.

This exhibition places your work alongside Roo Dhissou’s, whose practice is rooted in memory and institutional authority. What resonances or tensions emerge when your work is placed in dialogue with hers?

Jasmir Creed: Our practices mirror and contrast each other like light and shadow. My work often focuses on the personal, while Roo’s highlights the importance of the collective encounter. Together, we created a dialogue – like reflections, physical and metaphorical – which aligned with the ethos of without SHAPE without FORM, inviting audiences to understand themselves through community and daily practice.

photo by Taran Wilkhu,

Courtesy WITHOUT SHAPE WITHOUT FORM

Your palette moves between stark monochromes and intense vibrancy. Do you link

those shifts to psychological states, or are they driven more formally by the demands of each painting?

Jasmir Creed: I am driven formally by colour within each painting. It’s central to how I paint and I use it both symbolically and emotionally. Warm yellows may evoke intimacy, while cold blues suggest distance or anonymity. Sometimes I apply paint in flat layers, sometimes in translucent washes or rich impasto, depending on the subject. South Asian textiles, saris, or bangles bring their own expression into my work, contrasting with the often alienating cityscapes.

Many of your subjects seem to hover between visibility and invisibility. Do you see

painting as a way of amplifying overlooked presences, or as staging the instability of being seen at all?

Jasmir Creed: Both. My practice is shaped by hybridity navigating British and South Asian cultures simultaneously. That in-between state informs my figures: visible yet sometimes unseen, grounded yet dislocated. Painting becomes a way to honour that complexity, amplifying overlooked presences while acknowledging the instability of identity.

As your work enters collections such as the Imperial War Museum North, how do you feel about your paintings being framed within institutional narratives of history, conflict, and nationhood?

Jasmir Creed: It’s affirming, but I’m conscious of how underrepresented British South Asian women remain. Opportunities can be limited by how they are viewed and by the work they make. Work about identity politics is seen as more valid but many of these artists want the freedom to explore human experience. The failure to recognise this can be a form of racism in of itself. That’s why I also co-curate projects like Many Stories (Midlands Art Centre 2027), which will feature 15 British South Asian figurative women painters. For me, it’s important to inhabit multiple art worlds – institutional, community, and commercial – while pushing for visibility and agency for underrepresented artists.

photo by Taran Wilkhu,

Courtesy WITHOUT SHAPE WITHOUT FORM

You balance painting with curating and public programming. Do you see yourself

primarily as an artist producing objects, or as a cultural worker shaping conversations around identity and belonging?

Jasmir Creed: I see myself as an artist and as a cultural worker shaping conversations on both identity and belonging. Painting is at the core of my practice, but curating and programming are extensions of my research, sparking dialogue and collaboration. Through projects like InterWorlds: Transcultural Hybridity in Art, at Slade (2021 – present) and Many Stories at Midlands Art Centre (2027), I’ve worked to explore transcultural hybridity, while broadening the conversation around identity and belonging.

At its core, what does being an artist mean to you? Beyond the canvases you create,how does art shape the way you think, live, and move through the world?

Jasmir Creed: For me, being an artist means being curious and staying open to the world around me, transforming those perceptions through paint. Each gesture, each colour becomes a way of constructing space, much like an architect designs with form. Art shapes how I think and move through the world, turning lived experience into something shared.

©2025 Jasmir Creed