After 5,000 miles on the road, artist James Vaulkhard returns not with answers, but with landscapes that hold memory, contradiction, and the flickering afterimage of a national ideal.

There’s a moment, somewhere along the Missouri River, when the artist James Vaulkhard puts down his brushes and picks up something else entirely. It’s not just a shift in medium—it’s a shift in listening. The land, he realises, won’t be captured through careful observation alone. It needs to be felt in motion, caught in the blur between beauty and grief, awe and unease.

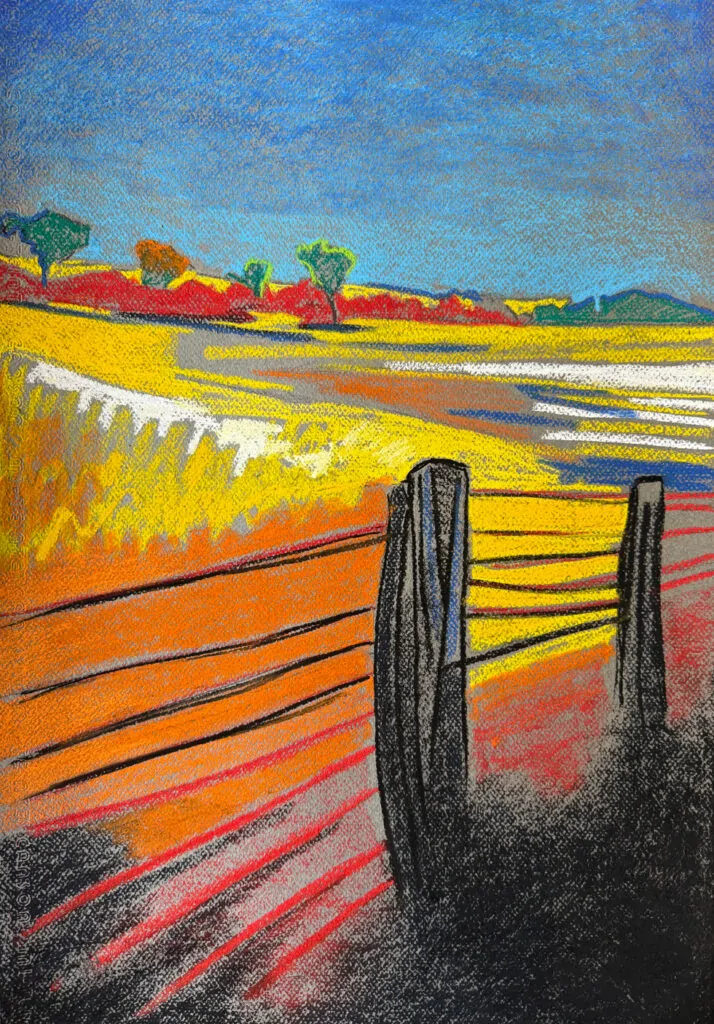

The Sublime & The Consumed, his latest body of work, was forged over 5,000 miles of American road, guided more by instinct than itinerary. What emerges is a series of landscapes that are as much psychological maps as they are geographical ones. Rooted in the lineage of the Hudson River School yet distinctly contemporary in its unease, Vaulkhard paints not nostalgia, but something far more intricate: the afterimage of an ideal, seen through the cracked lens of history.

Image courtesy of the artist

There wasn’t a single landscape that stood out. It was more of a gradual, unfolding dialogue between myself and the land

James Vaulkhard

But this body of work didn’t begin in a studio. It began beside rivers and motorways, in the slipstream of Hells Angels and the echoes of lost battles, with oil pastels pressed against wood panels balanced on the bonnet of a car. Vaulkhard’s process is as nomadic as his subject—less a search for fixed meaning than an invitation to witness the land as it is now: layered, altered, alive with contradiction.

In his paintings, light doesn’t just illuminate—it withholds. Golden fields glow like memory, while shadows pool with quiet dread. Detail is both present and withheld, as if the land itself were deciding how much of its story to share. There’s a quiet friction here: between reverence and ruin, wilderness and what we’ve made of it.

But Vaulkhard isn’t trying to resolve that dissonance. He’s sitting inside it, letting it colour the work. The sublime, as he sees it now, isn’t a grand or transcendent escape. It’s layered. It’s haunted. It’s still beautiful—yet that beauty has grown teeth.

What follows is a conversation that travels, as his paintings do, across terrain both real and imagined—from battlefield dawns to roadside epiphanies to colour fields trembling with meaning. In Vaulkhard’s hands, the American landscape is no longer a stage for expansion—it becomes a memory, a mirror, and a question we’re still learning how to ask. Vaulkhard isn’t painting what the land looks like—he’s painting what it remembers.

James Vaulkhard: The Sublime & The Consumed is on view until the 9th of May, 2025 at Blond Contemporary

Your exhibition, “The Sublime & The Consumed”, was born out of a 5,000-mile odyssey across the United States. What was the turning point on that journey—the moment you felt the work begin to crystallise?

James Vaulkhard: An interesting turning point came just outside Kansas City, along the Missouri River. I’d pulled over with the intention of working en plein air— with an easel and brushes, setting up carefully to capture the landscape. But almost immediately, something felt off. The process was frustrating, almost performative, and I couldn’t connect to what I was seeing or feeling. I remember a group of Hells Angels roaring past on the road behind me, and it just added to the sense that I was in the wrong place, doing it the wrong way. So I packed everything up and kept driving.

Later that afternoon, I pulled over & reached for a box of large oil pastels I’d picked up in New York and made a spontaneous decision: I left the brushes in the bag and started drawing directly onto the wood panels I’d prepared for those traditional studies. I stood with the panel on the bonnet of the car and started working. That moment changed everything. Suddenly I could move quickly, respond instinctively, scribble, mark, capture what I was seeing and feeling with immediacy and expression. That was a good moment. I’m still buzzing from that.

Oil stick & pastel on wood panel,

60 x 45 cm, 2025

Image courtesy of the artist

Was there a particular landscape or site that felt especially emblematic of the tension between preservation and consumption? Could you describe that encounter and how it made its way into your work?

James Vaulkhard: There wasn’t a single landscape that stood out. It was more of a gradual, unfolding dialogue between myself and the land. What struck me most, in truth, was the sheer vastness and beauty of the countryside. The culture—small towns, country music, the rhythm of a different kind of life—all of that wove its way into the experience and kept me engaged.

At one point, a close friend sent me a podcast about the Indian Wars, Crazy Horse, Custer, and the lead-up to the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Its not something a knew anything about or had any intention of exploring but I happened to be near the Bighorn River at the time and decided to camp nearby. What I didn’t realise was that I’d spent the night on the battlefield itself. I walked up the hill to visit the cemetery at dawn. It wasn’t intentional, but it became without question one of the most poignant parts of the trip for me. It feels almost taboo to talk about.

One of the final pieces in the series is of the Bighorn River. It’s perhaps the most ethereal of them all.

75 x 54.5 cm, 2024

Image courtesy of the artist

You’ve drawn inspiration from the Hudson River School, a movement steeped in 19th-century optimism and reverence for untouched wilderness. How did physically tracing those landscapes, now altered, influence your perception of the American ideal?

James Vaulkhard: I first encountered the Hudson River School through an exhibition at the Tate when I was younger—it made a strong impression on me, even though, admittedly, my knowledge of American history at the time was limited, and still is in many ways. For this project, I decided to loosely follow the route Lewis and Clark took in 1803. That choice wasn’t about historical accuracy as much as it was about physically moving through a landscape that had once symbolized the edge of the known world—a kind of blank canvas for American ambition and expansion west.

Spending that much time alone on the road gave me space to not only absorb the scenery but to really reflect on what those early painters were seeing, and what they were projecting onto the land. The wilderness they depicted with such reverence has, in many places, been completely transformed. Tracing those landscapes now, altered by infrastructure, industry, tourism—it made the gap between the ideal and the reality feel stark. But it also added depth. The sublime isn’t gone, but it’s complicated. It’s layered with human history, with impact, with contradiction. That quiet reflection—on the road, in the landscape—became as important to the work as the visual references themselves.

Oil stick & pastel on wood panel,

60 x 45 cm

Image courtesy of the artist

The concept of the sublime has traditionally implied grandeur, transcendence, even spiritual elevation. In your work, that notion feels increasingly troubled by darker, more ambiguous elements. How do you define the sublime today—has it become more of a warning than a wonder?

James Vaulkhard: I think the sublime today still carries that sense of awe and wonder, but it’s no longer purely uplifting or spiritual in the way it may have been traditionally understood. Historically, the sublime had a religious sensibility—like the grandeur of the Baroque, it was meant to elevate, to overwhelm the senses and connect us to something greater. In our time, that feeling can come from things like space exploration or artificial intelligence—experiences or phenomena that inspire awe, but also a certain unease or disorientation. There’s a tension there, and that’s what I’m trying to tap into with some of the art works.

So yes, my paintings engage with the darker, more ambiguous side of that feeling, but they also hold onto wonder. They’re colour paintings, and people often respond to the colour first—there’s a kind of lightness or beauty that draws you in. That initial attraction is important. Then, maybe as you spend more time with them, something more complex starts to surface. I think the sublime today isn’t necessarily a warning—but it is layered. It asks us to sit with both the marvel and the discomfort, the light and the shadow.

42 x 59.5 cm, 2025

Image courtesy of the artist

You often use light and shadow as symbolic forces. In “The Sublime & The Consumed”, how does this play reflect your view of contemporary environmental and political anxieties? There’s an almost mythic tone to your use of colour—fields of gold, sudden darkness, obscured details. Do you view your landscapes as allegories? If so, who or what are the protagonists in this American story?

James Vaulkhard: The political aspect wasn’t at the forefront when I set out on this journey—these paintings aren’t intended as direct political narratives. It’s more that the timing of the trip, and everything happening in the background—environmentally, culturally, politically—naturally started to seep into the work. I’m someone who cares deeply about the environment, so those concerns inevitably found their way in. It felt important to acknowledge them, even if subtly.

I did begin thinking more consciously in terms of allegory—not in a rigid or symbolic sense, but as a way of layering meaning. Light and shadow play a big part in that. I use them not just to structure the image, but to suggest mood, ambiguity, even a kind of mythic or emotional truth. The golden fields, the sudden patches of darkness, the blurred details—they’re all ways of asking questions, not offering answers.

As for protagonists—I think the land itself is the central character. But it’s haunted by presence: the traces of people, of industry, of history. Sometimes it’s my own shadow in the landscape. Sometimes it’s a path or structure or vehicle that implies human passage. The story isn’t about one person or event—it’s about a place that has held many stories, and how it feels to stand there now, aware of everything it’s seen.

©2025 James Vaulkhard