Collage is arguably the most fascinating kind of medium for an artist to undertake in their practice. In collage, artists are tasked with finding synchronicities among acausal connections, acting as a forager of cultural imagery and chasing narrative structures that follow form, colour, and shared photographic histories. Using photography, video, installation, and a range of found images from second-hand shops, Aikaterini Gegisian excels in the practice of collage-making, elevating it to a conceptual plane that deconstructs, decontextualizes, dissects, and melds seemingly fragmented realities together.

In her work, the act of removal becomes an act of trans-historical unification that challenges our perceptions of time, form, and identity. Gegisian archives popular culture and nationalist identities and ideologies, often incorporating the spanning, layered landscapes of the Ottoman and Soviet Empires as grounds for fieldwork. Sometimes, this means using temporal visual markers alluding to a time and place stuck within a collective register of image/colour association.

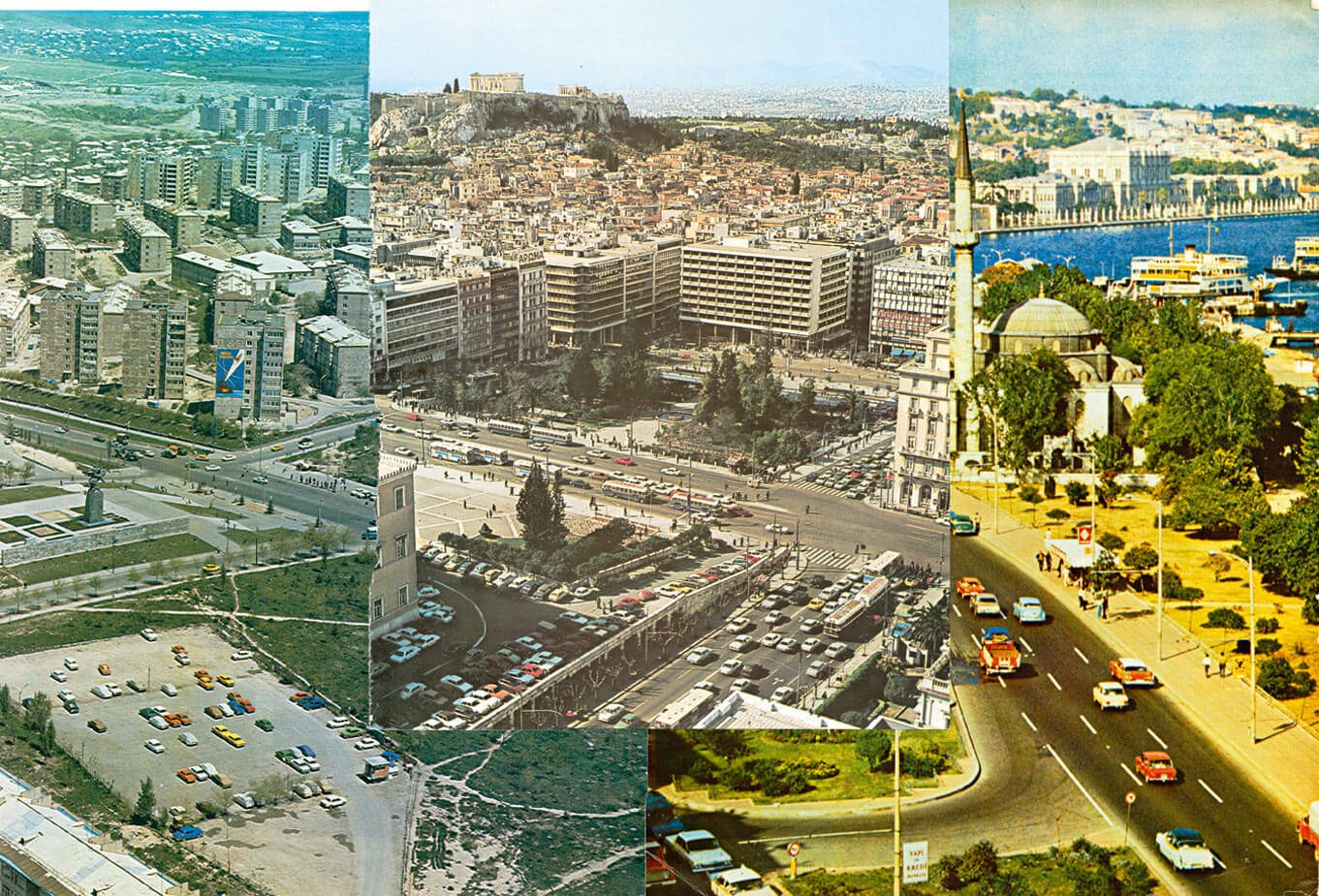

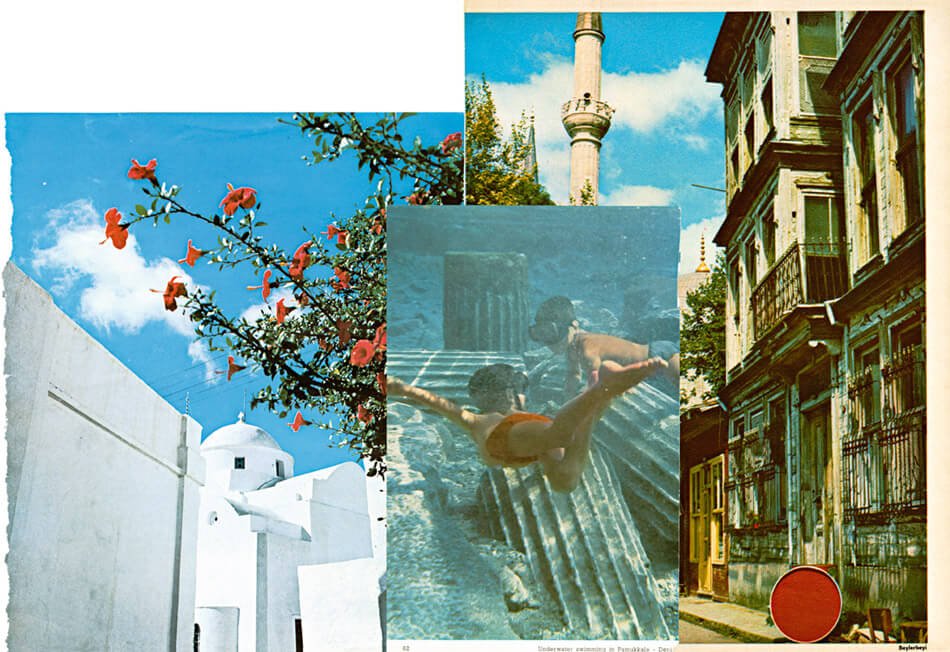

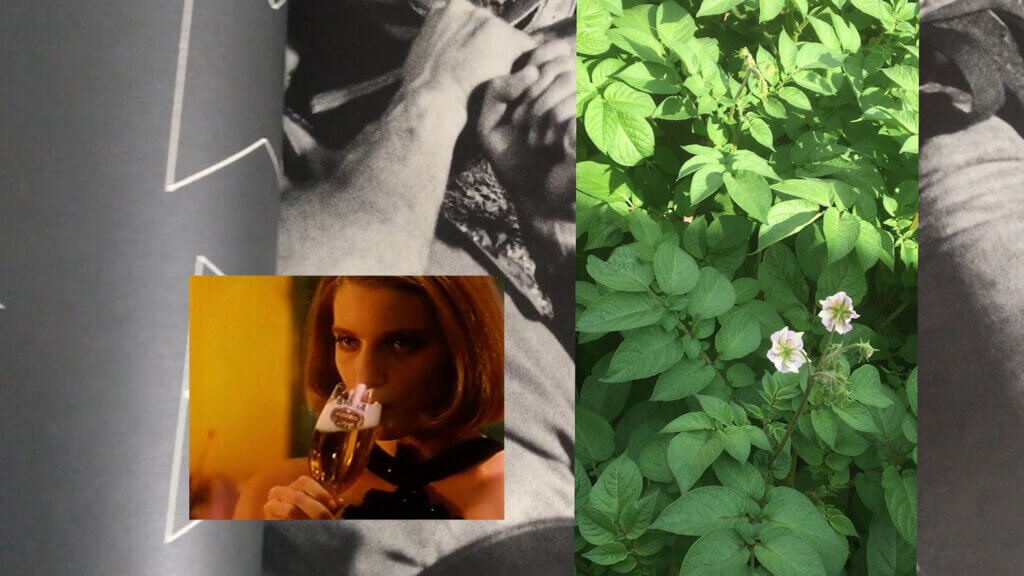

In Formless Forms, colour grading is used to mimic the way the sun’s light changes the colour of a landscape, mapping the passage of time to colour associations linked to specific decades. Gegisian uses saturated images sourced from Greek, Turkish and Soviet Armenian tourist catalogues that call back on the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, akin to the filters that we used in the early days of Instagram, or the yellowish sepia tint filmmakers use whenever they depict a country outside North America or Europe.

Aikaterini Gegisian, Formless Forms, 35 mm slide projection, 5 mins, 2015

The lighting in print photographs is one of the reasons why Gegisian collects images from the 1960s-80s, during a period of changing technologies that would jump-start contemporary new media. Formless Forms accomplishes in a projected slideshow time-lapse what some videography cannot: it depicts inter-sensory, cross-cultural experience as it connects to a natural—yet finely curated—colour palette.

This also alludes to what Gegisian refers to as a depiction of the exoticized “other,” as assigned to folkloric motifs deemed “inappropriate” for some sub-cultural spaces and celebrated in others. Accordingly, it is that sense of saturation in photography and film that characterizes tourist imagery, or what we now call kitsch and display ironically in second-hand shops, relaying any appreciation of these images to those celebrating their “camp” qualities.

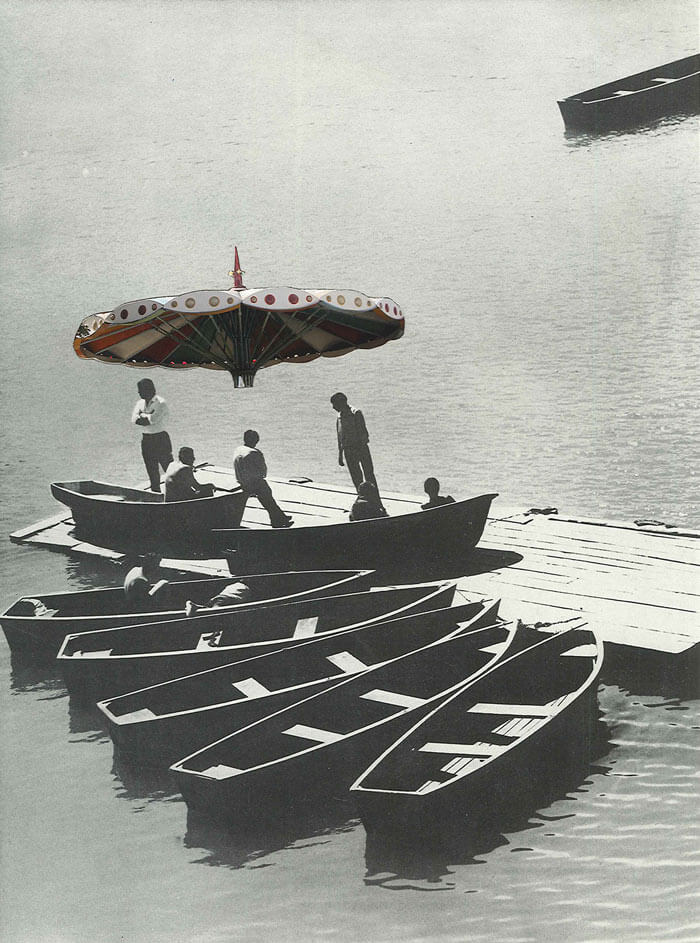

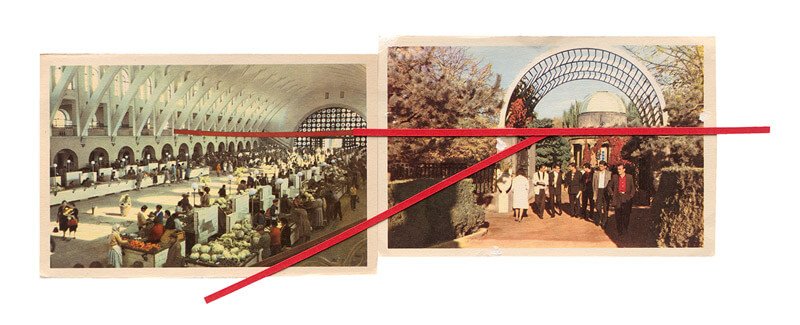

Gegisian characterizes Soviet Armenia’s past as a trick of nostalgia, a side effect of the ever-fleeting concept of modernity, in A Little Bit too Much, A Little Bit too Late. Like so much of Gegisian’s work, the series of 50 collages are meant to investigate and dismantle our perceptions of historical memory as consumers. We consume the world through images of places we see as distant and different, rendering them easier to alienate spatially, historically, and culturally. Applying decontextualized objects like lamp posts, street signs and gas pipes as decorative motifs, Gegisian juxtaposes ideas of the country with urban life and man-made materials. As she notes, these images and materials imprint themselves in our memories as tools of assimilation, as “shapes” of cultural and individual identifiers found within a wider landscape of interlaced symbolism.

Left: A Little Bit too Much, A Little Bit too Late (Rest 1), collage on paper, 33 x 25 cm, 2011

Right: A Little Bit too Much, A Little Bit too Late (Spring 2), collage on paper, 33 x 25 unframed, 2013

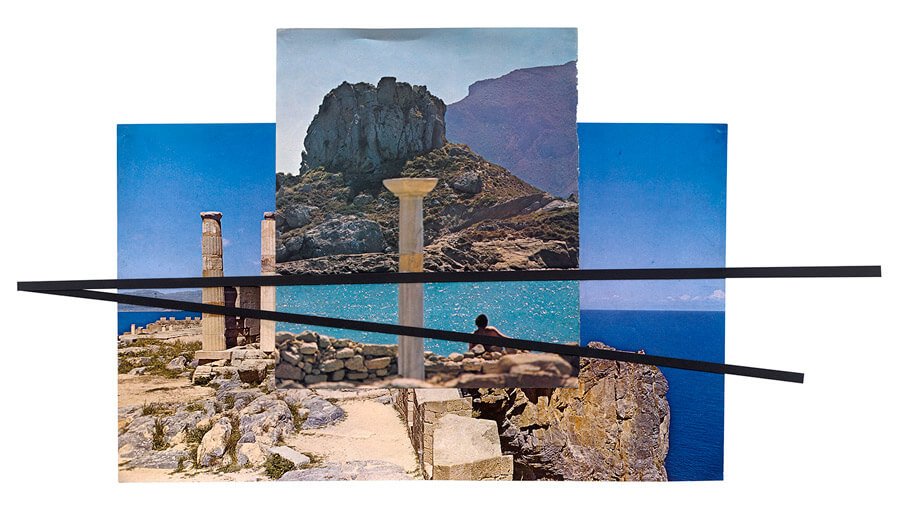

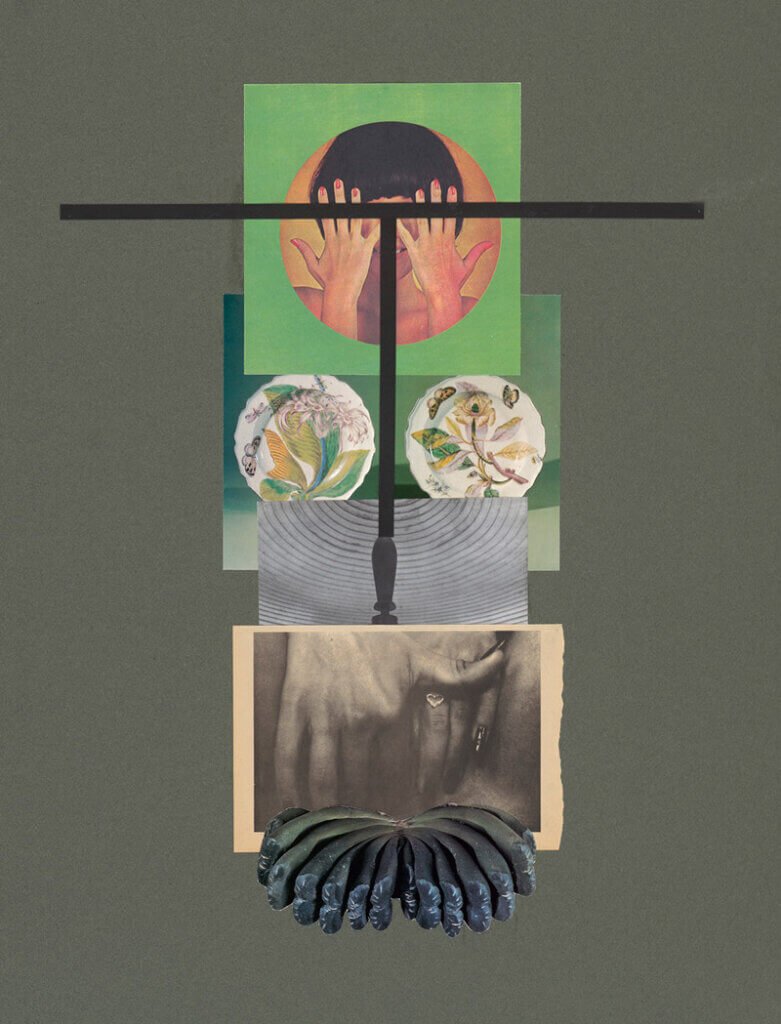

Gegisian adopts that archive of photographs of Soviet Armenia, Turkey and Greece from the 1960s to the early 1980s in A Small Guide to the invisible Seas. These reinvigorated albums serve as biographical depictions of Gegisian’s own identities and the overlapping narratives amidst fixed points marked by architecture, landscape, and ruins with the combined usage of leisure and labour that connects one era to the next. Utilizing the same pool of images, Gegisian created the Red Line, Blue Line, and Black Line trilogy, borrowing constructivist motifs to highlight lines of censorship and disruption across visual cultures in post-war East Germany, Soviet Armenia, and postmodern US popular culture.

While A Small Guide to the Invisible Seas functions as a palimpsest of material, the Red, Blue, and Black Line trilogy applies, then dismantles, recurring symbols in a tongue-in-cheek fashion.Photography, in the artist’s words, often creates and reshapes a figure or idea, and other images act as either reinforcements of subliminal, aesthetic, and ideological messaging, or give rise to new meanings in perception. Gegisian both destructs and connects these ideas so we question such messaging while exploring contemporaneity in displacement.

Self-Portrait as an Ottoman Woman, for example, forges that space of belonging for women separated by time, borders, and the freedom from the ambiguity of individual female voices lost to heterogenous conventions of empire. Snapshots of femininity serves as an institution, as an indoctrination of sorts, in I was a Victim of my own History consists of a funeral wreath comprised of images of floral arrangements.

Left: I was the Victim of my Own History, Sculptural collage, found images, cardboard, Dimension: 200 cm in diameter, 2018. Installation Shot, [un]known destinations, chapter II, 15th High School of Kypseli, Athens, 26 June – 24 July 2018

Right: I was the Victim of my Own History, Sculptural collage, found images, cardboard, Dimension: 200 cm in diameter, 2018, detail

The work is unsuspecting at first, yet Gegisian manages to celebrate, mourn, and dispute the flatness of preserved female domesticity. As an archivist whose work functions as a study in normative ideologies, gender, and popular culture, she is like an anthropologist working from the inside-out, without the burden of a normative western male gaze.

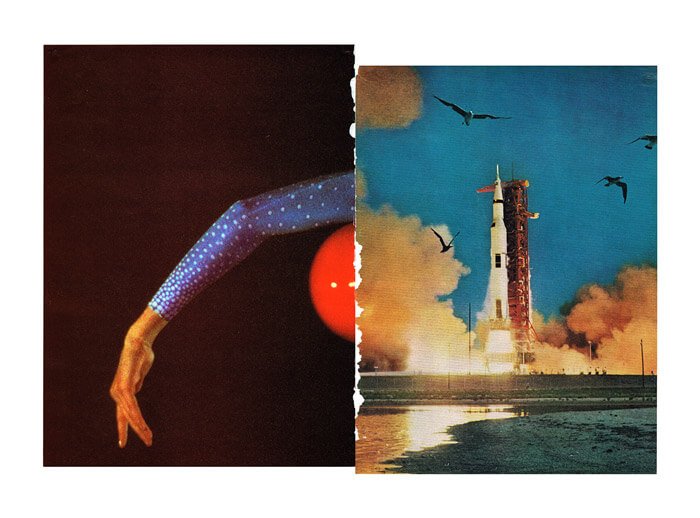

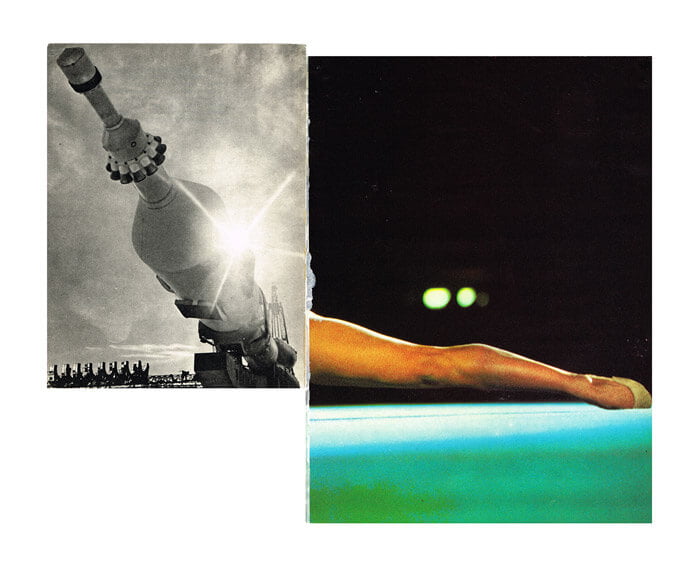

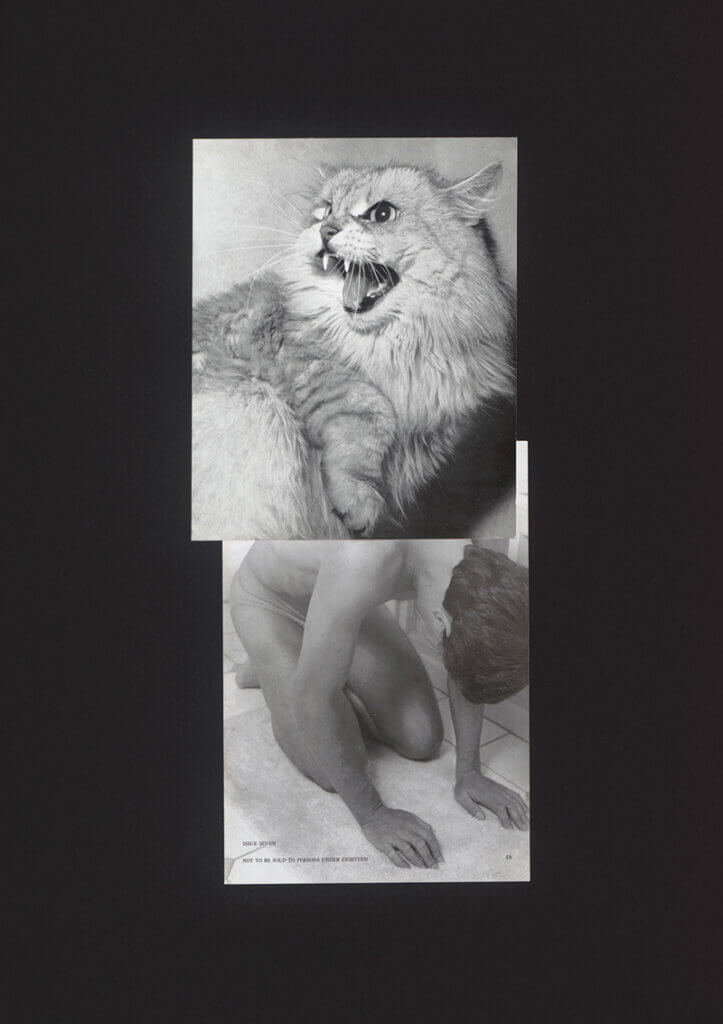

In Is This Why I Cannot Tell Lies? The artist challenges hegemonic physical norms of sexuality through movement—be it the movement of people, time, or a celestial body—to illustrate the literal and metaphorical positioning of female figures, blurring the lines between fantasy and reality. Photographs of gymnasts, flowers, planetary objects, and birds in her Falling Tight series create the illusion of visual gravity across each work. Narratives of possibility, freedom, and metamorphosis are placed there, beyond the limitations of prescribed female imagination. The notion of a female gaze is inherent in Gegisian’s practice of revisiting, rereading, and reimagining form, in the eroticism of found images and the hyper-awareness of female experiences across patriarchal fault lines.

Left: Falling Tight I, Photographic readymade, found images, 29.8 x 42.5 cm unframed, 2014

Right: Falling Tight VI, Photographic readymade, found images, 30 x 38 cm unframed, 2014 Much, A Little Bit too Late (Spring 2), collage on paper, 33 x 25 unframed, 2013

My Pink City serves as both a study in the female gaze and a sliver of post-Soviet Yerevan, Armenia. In Yerevan, Gegisian felt her gaze as a woman holding a camera in direct conflict with patriarchal spaces, seen whenever her camera pans to military parades, found propagandist footage, or the intense stare of a man in uniform sitting on a public bench. We feel enticed by the self-consciousness of Gegisian’s Yerevan, a consciousness we know as fleeting and short-lived within the span of 48 minutes.

It leaves us wanting to also understand the space between a Soviet Armenia and its modern, capitalist counterpart, giving off the illusion of a controlled cityscape within these fragments of life in Yerevan while teasing the stories beyond the frame. Last year, Gegisian published the Handbook of the Spontaneous Other, a collection of 59 collages on paper that culminate the female gaze as a combatant to consumable images of sex and an “ideal” lifestyle produced by popular media.

Produced from photographic materials produced in Western Europe and the USA during the 1960s and 70s, the handbook stems from Gegisian’s observation of the very Western continuum of labour, consumption and sexuality, all manifesting in the artist’s fascination with the photobook form. Lifestyle magazines, copies of tourist catalogues and issues of National Geographic are meshed with erotic and nude photography to comment on depictions of bodies as they connect to dance, sex, commerce, and labour. How are these concepts irrevocably intertwined and sold to us? Here, Gegisian’s “other” seeks to find form in spontaneity outside conventional modes of representation.

Further exploring mixed media and bookmaking, her craft culminates in the dynamic four-year project on post-WWII European integration, Third Person (Plural), adapting footage from newsreels and US informational films into—what else—a book that exemplifies her artistic hybridity. Along with the development of Exercises in Speaking Out, which equates documented images of women with tech manuals, she looks to new works on ideas of survival and finding one’s voice as a woman, as brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdowns, in her new YouTube channel, The Manipulator Vlog.

Building on her own metanarratives, Gegisian continues to add to the rich canon of imagery and form she has unearthed, with a dash of humour pointed at those who characterize her work under generalized neoliberal descriptors. She asks us to not only point the proverbial finger at a world manufactured by imagery, but to ourselves as spectators of her work, cloaked in the convenient terminology of art world globalism.

Q: What was your first major aesthetic experience that led you to become an artist?

A: I grew up in Thessaloniki, Greece and when I was a teenager, in the 90s, the city didn’t have much of a visual art scene or contemporary art museums for that matter. Things have changed and Thessaloniki now boasts MOMus (The Metropolitan Organisation of Museums of Visual Arts of Thessaloniki) which is unique for Greek standards. However, since the 1960s the city has been home to a major International Film Festival. The festival (TIFF) was the site of my first formative aesthetic experiences.

I cannot recall a specific film or director (or auteur if we are talking of art cinema) but rather the experience of spending days on end watching a diverse array of films, being absorbed into a world of images and stories. This sensation is still present in my practice, as the preoccupation with image making and narrative structures.

Q: Break down the steps you take in your research of found images. What does your creative process look like?

A: The first step is the sourcing of images, an activity that primarily involves the collection of photographic books. The spark (the inspiration behind each collection) is usually an interest in a particular image history. For example, during a residency in Halle 14, in Leipzig last autumn, I started collecting books published during the post-war years in East Germany. Slowly, I narrowed down the scope of the collection, and in the case of the Leipzig residency, I focused on the production of East German nude photography and erotica from the 60s to the 90s. Once I focus my research, the process of reading the photographic books begins by identifying photographic topologies, motifs, repetitions and finally by dismantling the books and organizing the images into categories.

In that stage the connection with other image histories comes into play, as my practice usually brings into ‘inappropriate’ dialogue images produced in diverse historical, geographical, and ideological contexts. This ‘inappropriate’ dialogue, expressed as collage making, is my strategy for interrogating the social function of photography and for investigating how photographs shape and reshape bodies and identities, since the collision of contradictory meanings opens up gaps in perception.

Q: What piqued your interest in working within the realm of found photography and collage?

A: Having been mostly inspired by cinema, as I described in your first question, I spent almost a decade after graduating working with moving images. My early video works address subjective dislocation, shifting geographies, place and belonging, and intercultural flows. They are marked by a layering of diverse geographies and mental states.

This layering (which in retrospect seems like my first engagement with the notion of collage) progressively turned into an engagement with different cinematic languages, epitomized by My Pink City (2014), a medium-length essay film. The film investigates the urban transformation of Yerevan (the capital of the Republic of Armenia), documenting the post-Soviet transition of its urban landscape.

It was during fieldwork in Yerevan, that I started researching Soviet Armenian visual culture and especially how the city has been documented, in order to understand the transition that I was trying to describe. I came across the rich state organized photographic and documentary production in the former Soviet Union, which drew my attention to the role of photography as a tool of propaganda and as a mechanism for shaping specific interpretations of cultural and national identities. I started collecting Soviet Armenian commemorative albums and tourist guides and produced my first collage series A Little bit too Much, A little Bit too Late (2011-2013).

Q: What major themes or findings have you encountered in studying the role of historical memory and collective identity as it pertains to ideology, tourism, and/or nationalism?

A: When I started researching the photographic production of individual nations or specific geographies, I realized that my focus was always on popular culture, on images widely circulated in the public sphere through the popular illustrated press or photobooks that entered people’s houses. That’s why I source my material through flea markets and second-hand books shops, where the remnants of past lives lie, rather than research official archives. I focus on widely distributed and commonplace images because I want to identify specific public spheres produced by photography.

I want to understand how photography constructs specific ways of imagining communities and landscapes though images. In that sense, my first major finding is rethinking photography, not only as an aesthetic experience but as having a wider social function, of photographs as contextual documents that shape collective memory and identity. Another major finding is that usually these photographic public spheres are formed by the popular western representational languages of adventure and exploration, of tourism and travel. I have worked extensively with tourist photography, which I came to understand as a nation building mechanism, recognizing that popular tourist images are instrumental in reinforcing national identities.

Q: What is the significance of your interest in colour, as it relates to lighting, time and landscape, or even the filters we now associate with “vintage” photographs?

A: Inspired by the movement of the sun changing the forms of the landscape, colour has become central in my practice both as a way of questioning the production of the photographic image and as a way of creating narratives. Firstly, colour is part of the history of photographic technologies, tied up with the advancement of chemical processes resulting in the production of different colour palettes and hues. This is evident in print photographs and is one of the reasons why I collect material from the 1960s to the 1980s. During this time period, the changes in colour technology and shooting styles (for example the use of colours as studio backdrops) enables one to locate the image temporally. What we assign as “vintage” photographs is the fact that we recognize based on colour when the photographs were produced and printed. However, although colour is part of how we read images, it still has an ambiguous function in the way we assign value to photography, especially art photography, with black and white images associated with higher aesthetic values.

I also focus on colour because I want to address the fact that although it is part of western cultural narratives, for example the colour blocking of interiors, the colour charts of corporate culture, the colour of modern plastic or colour in popular culture, it is also relegated to the exotic other, to the folklore or kitsch. The use of colour is a way of bringing together these different cultural registers and references, since such ‘inappropriate’ dialogues are the basic mechanism of critique of dominant narratives in my work. Finally, in a more experiential level I associate colour with light, the light of the sun that changes the colour of the landscape and the light that enters the photographic camera eye. This is again a temporal association that allows me to map the change of colour to the movement of the sun and thus to the time passing. This metaphor is the basis of the narrative structure of my recent collage photobook Handbook of the Spontaneous Other (2019), which consists of 9 colour sections that echoes the form and flow of the rainbow.

Q: You are Greek-Armenian and often allude to the homogenous nature of a perceived cultural identity. How is that contextualized in your body of work?

A: My mixed Greek-Armenian heritage has produced a fluctuating sense of identity, commonly associated with diasporic experiences. From early on, this in-betweenness drew my attention to the many processes of identification and the processes of constructing national, cultural and gender identities. On one hand, being between cultures, geographies and histories allows a critical distance, and on the other hand it generates a desire for building bridges that connect cultural experiences that are separated by national borders.

All of my grandparents (Greek and Armenian) became refugees with the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, so the wider Ottoman landscape has become a territory that I have often called upon. For example, A Small Guide to the invisible Seas (2015) is based on an extensive collection of photographic albums of Soviet Armenia, Turkey and Greece dating from the 1960s to the early 1980s. Although the work critiques the role of tourist photography in constructing the image of nations, the choice of locations reflects my own biography. The ‘inappropriate’ bringing together of Soviet Armenia, Turkey and Greece, of the different geographical, ideological and historical contexts constructs a new landscape, unearthing an invisible topography, which on a personal level becomes my imaginary place of belonging.

Another work that explores the transitory post-Ottoman context is Self-Portrait as an Ottoman Woman (2012-2016). The work is a collection of 99 popular postcards of women in traditional costumes and national dresses that geographically represent the whole of the post-Ottoman landscape but chronologically reference various historical moments and national contexts. The idea of the ‘Ottoman Woman’ is constructed by another ‘inappropriate’ dialogue, by bringing together postcards from Ottoman, orientalist, and nationalist perspectives. This ‘inappropriate’ grouping creates a new space of belonging for women that were separated by national and cultural borders and produces a new collective body. The category of the Ottoman woman is ambiguously posed as a potential space for subjective identification. By making a self-portrait, I am attempting to draw another imaginary place of belonging.

Q: How and why does movement show up as a central theme in your work?

A: Movement, as in the traversing of land, is a crucial element of the diasporic experience. Movement is also crucial to how time and space is constructed and experienced in moving image practices. It is through movement that cinema produces the idea of time pacing and the idea of crossing space. As I mentioned already, my early video works explored subjective dislocation and focused on movement as a part of the diasporic experience.

These early video works—for example, the day that left (2002); Tokyo Tonight (2003); A little film (2006)—not only documented the movement between different geographical spaces but were further punctuated by a camera on the move, drifting from urban and emblematic landscapes to mental and memorial spaces. As my practice evolved, movement transformed into the ‘inappropriate’ collaging of diverse aesthetic languages and of disparate image histories.

The collaging of heterogeneous material acts as the facilitator of movement between visual cultures, aesthetic languages, [and] geographical and historical contexts. This in turn both echoes the qualities of cinematic narrative that I mentioned above and sets images in a constant state of flux. It is this jumping between references and languages, this movement of collaging ‘inappropriate’ material, that allows images to escape the ideological frameworks that construct them, evading western knowledge paradigms that fix meanings and narratives.

Q: Calling on series like the Red, Blue, and Black Line trilogy, do you see your work as a practice in the unity of figures and objects, or a practice in disruption?

A: Historically collage practices, from the photomontages of the Russian avant-garde to the surrealist phonograms, are associated with breaking dominant conventions and the radical potential of transforming the ways of seeing. This is usually achieved through fragmentation, by taking images out of their context and bringing them into new, often jarring, relations.

In my collage practice there is an element of fragmentation through the ‘inappropriate’ collision of diverse images and aesthetic languages, a practice of disruption as you describe it. It is also a practice of deconstruction, deconstructing the many structures of the images (they ways images are formed and organized) in order to reveal how knowledge is produced, how visual languages function. At the same time, because of my interest in narrative structures, I often focus on creating new image worlds that make visible new forms of imagination. On a deeper level, such strategy goes beyond a critique of dominant ideologies. The production of new imaginations is also a practice of—to use a fashionable word—decolonizing visual knowledge structures.

Q: The concept of the feminist gaze is often brought up in discussion of your work. What does the feminist gaze look like to you?

A: I first started addressing feminist questions in the essay film My Pink City (2014) filmed in Yerevan, Armenia. During my fieldwork in the city, the patriarchal structures of Armenian society made me aware that I was a woman holding a camera. This realization forced me to contemplate for the first time the female subjective position. My Pink City is a portrait of post-Soviet Yerevan, and in as much is also about the struggle of the female author to find her own voice. Initially the call for a feminist gaze was an attempt to make visible the female authorial position, to claim space from which to speak.

As my practice evolved towards expanded photography and collage, the feminist gaze became the strategy of rereading image histories that were shaped by patriarchal legacies. The process of rereading the collected popular and ‘inappropriate’ archives was an act made visible by the female gaze. More recently, as the notion of survival became an urgency brought about by the pandemic, I started rethinking the notion of survival in relation to the emancipatory act of learning to speak. Currently, I am developing new bodies of work where the process of finding one’s own voice (surviving) is equated with the feminist rereading of material produced by the male gaze.In simple terms, in order to survive it is imperative to reread patriarchal, imperial and colonial images histories through the casting of female or other gazes.

My Pink City, video still, essay film, 2014, 48 mins

Q: Do you have a favourite piece, series, or found image?

A: What I love and what inspires me are images—in the sense of visual languages—and a diversity of visual languages, from pop feminist avant-garde practices to Para Janov’s Transcaucasian surrealism. So, I have many favourites pieces, series and found images, which change over time, depending on my location and what I am working on. One of my greatest soft spots are images and representations of flowers and their many cultural iterations, from their association with the institution of femininity to their prevalence in vernacular visual cultures, to their use in Islamic motifs.

Q: What future projects and themes are you interested in exploring and developing?

A: The pandemic provided a fruitful moment for the female archivist in me, especially after the rediscovery of my teenage collection of Greek 90s lifestyle magazines. The rediscovery propelled the development of two new parallel bodies of work, the expanded photographic project Exercises in Speaking Out and the YouTube channel The Manipulator Vlog.

These works mark a departure from the ‘inappropriate’ collision of image histories based on specific geographical and national contexts of previous projects, and a move towards embodied knowledge (knowledge derived from living with images), especially after the experience of social distancing. Following the episodic structure favoured in my practice, both bodies of work bring attention to autobiography, and an intimate understanding of time passing, as these interweave with larger image histories.

In parallel, I am also finalizing the long-term archival project Third Person (Plural), (2017-2021), a collage film and multi-screen installation, composed of 8 episodes. The project is based on a collection of 160 Universal newsreels and 40 US government informational films produced between 1945 to 1957, focusing on the early history of European integration. Having just completed the full editing of all eight episodes, I am working on translating the archive material collected and the edited film into the book form, a book that will function as a catalogue, academic interpretation, and art book.

©2021 Aikaterini Gegisian