Massachusetts-based artist Emma Kohlmann‘s expression takes many forms, including drawing, zines, digital art, writing, and books. Renowned for their deep resonance, her paintings perfectly balance aesthetic appeal and conceptual depth. The tactile unpredictability of watercolour intertwines with the rich, black hues of the historical Sumi ink, which has become synonymous with Kohlmann’s work.

(Credit: Alexander Rotondo)

Abstraction was the way for me to corrupt the traditional tropes of sexual desire

Emma Kohlmann

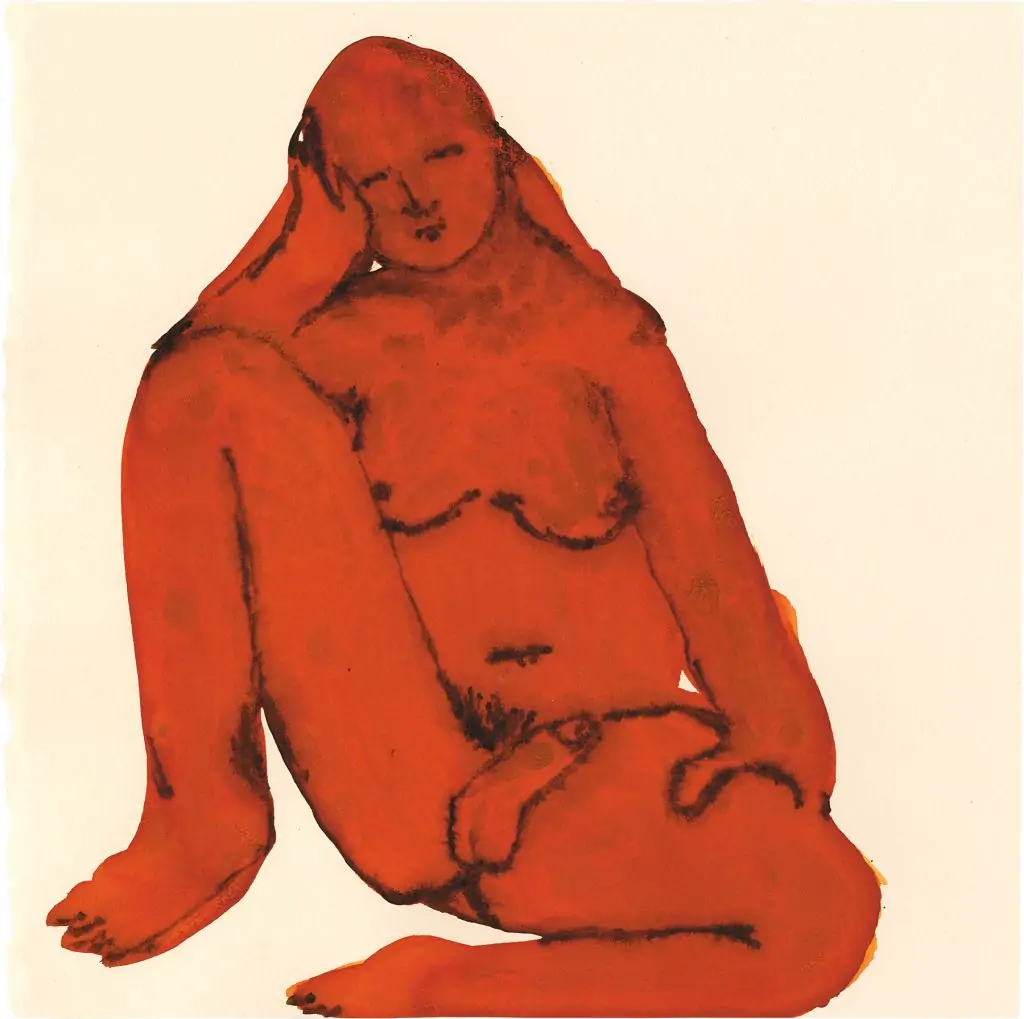

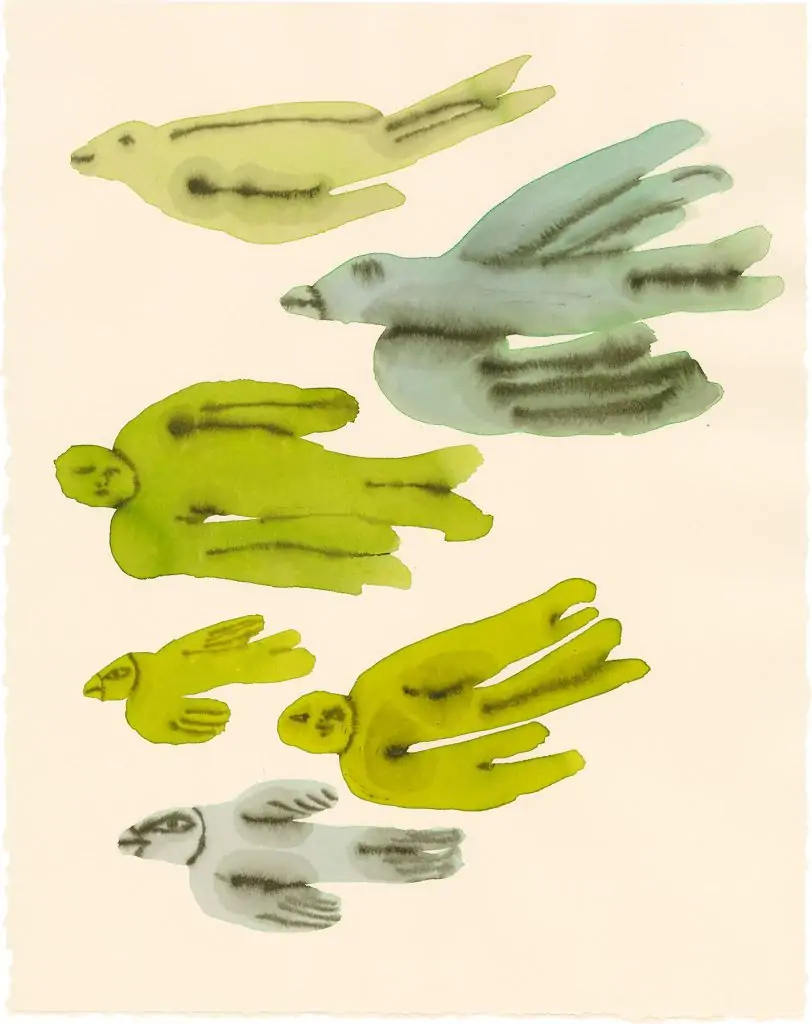

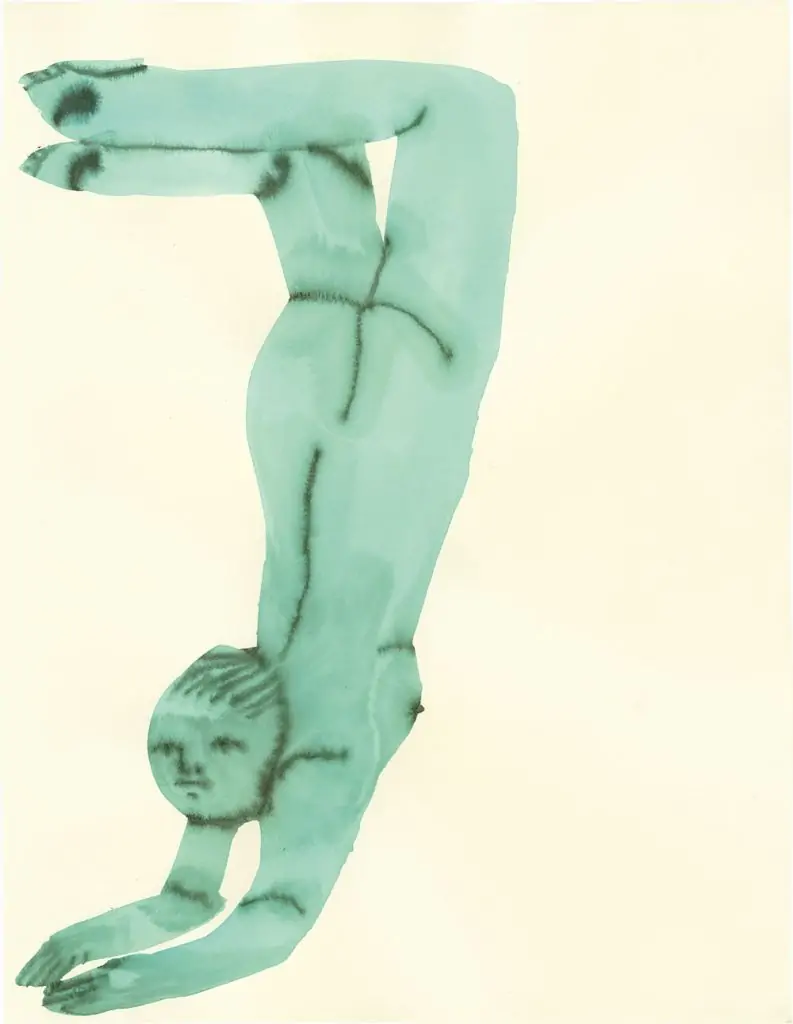

Through the fluidity of washes and blooms inherent in watercolour, Kohlmann boldly challenges the Western Canon of Art History. In raw and unfiltered depictions, Kohlmann peels the plaster off the wound we call the traditional male gaze. Delving into often taboo themes such as gender, societal issues, and the spectrum of sexuality and sensuality. Kohlmann unabashedly imbues her critiques on canvas and paper. Gentle gradients and saturated hues, intensified by delicate touches of ink, breathe life into her figures in a balletic interplay, bringing forth their ethereal appearance: figments of otherness as if they emerged from an alchemist’s dream.

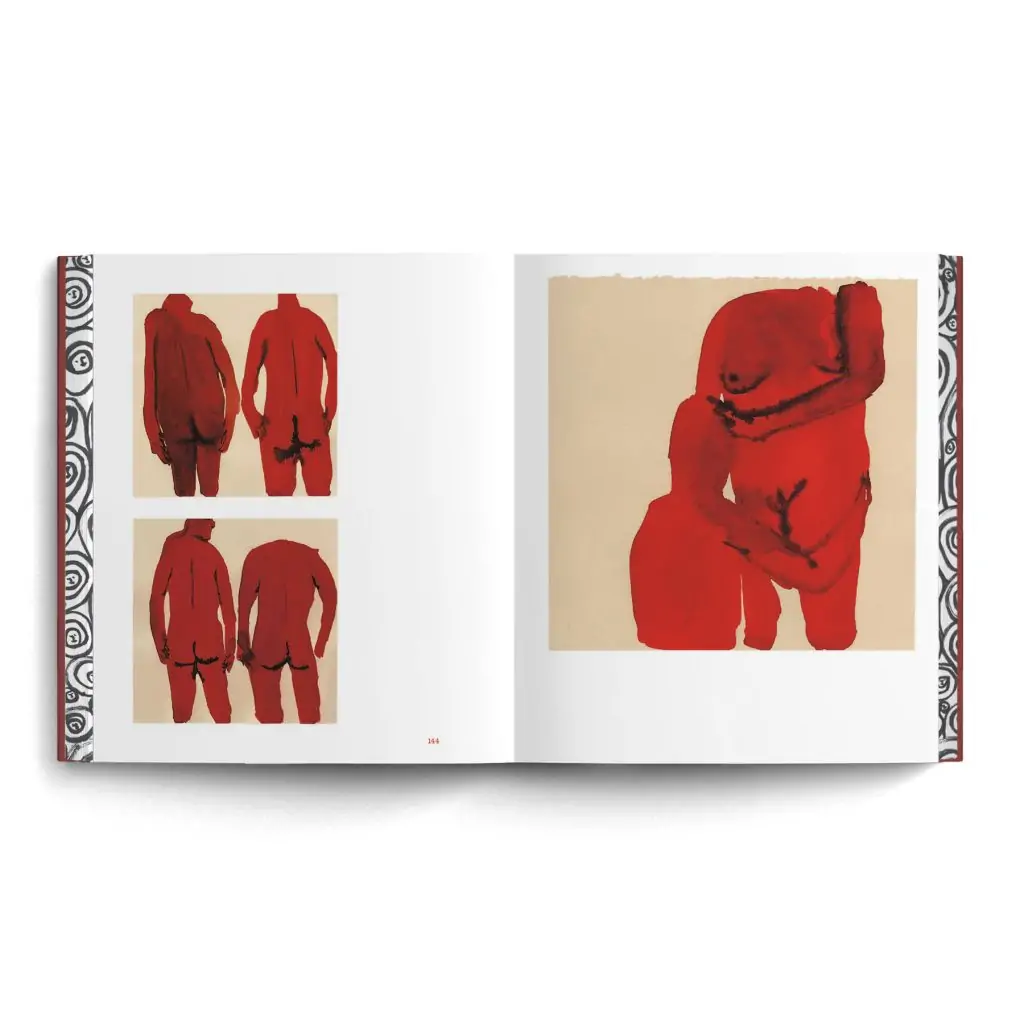

Strikingly rendered in a red hue synonymous with sensuality and bearing a countenance of historical portraiture yet, these figures are nonetheless minimal, presented as mere suggestions rather than detailed representations, flirting with the liminal space between the real and the imagined, echoing the unity and ambiguity of the human form, inviting viewers to contemplate the fluidity of gender and the essence of humanity.

Kohlmann deconstructs conventional interpretations of imagery, emphasising the political nature of the body. As Kohlmann says, “The body is political. There are aspects that are visible and others that are hidden. There are parts that are celebrated and others that are obliterated. I want it all to be acknowledged.” This approach reveals a layered complexity in her work, where every stroke, mark, and colour choice deliberately acknowledges the multifaceted nature of the bodily form.

Throughout Kohlmann’s paintings, she captures the immediacy and unpredictability of watercolour and ink, creating a bleeding effect where her figures are neither rigid nor definitive. I feel Kohlmann’s watercolour use can also signify the fluidity and ever-changing aspects of identity, gender, and society.

Kohlmann’s works evoke complex layers, reflecting on the state of humanity caught in the paradox of progress and regression and serve as a catalyst for introspection and discourse, inviting you to dive into the high seas of conceptualisation.

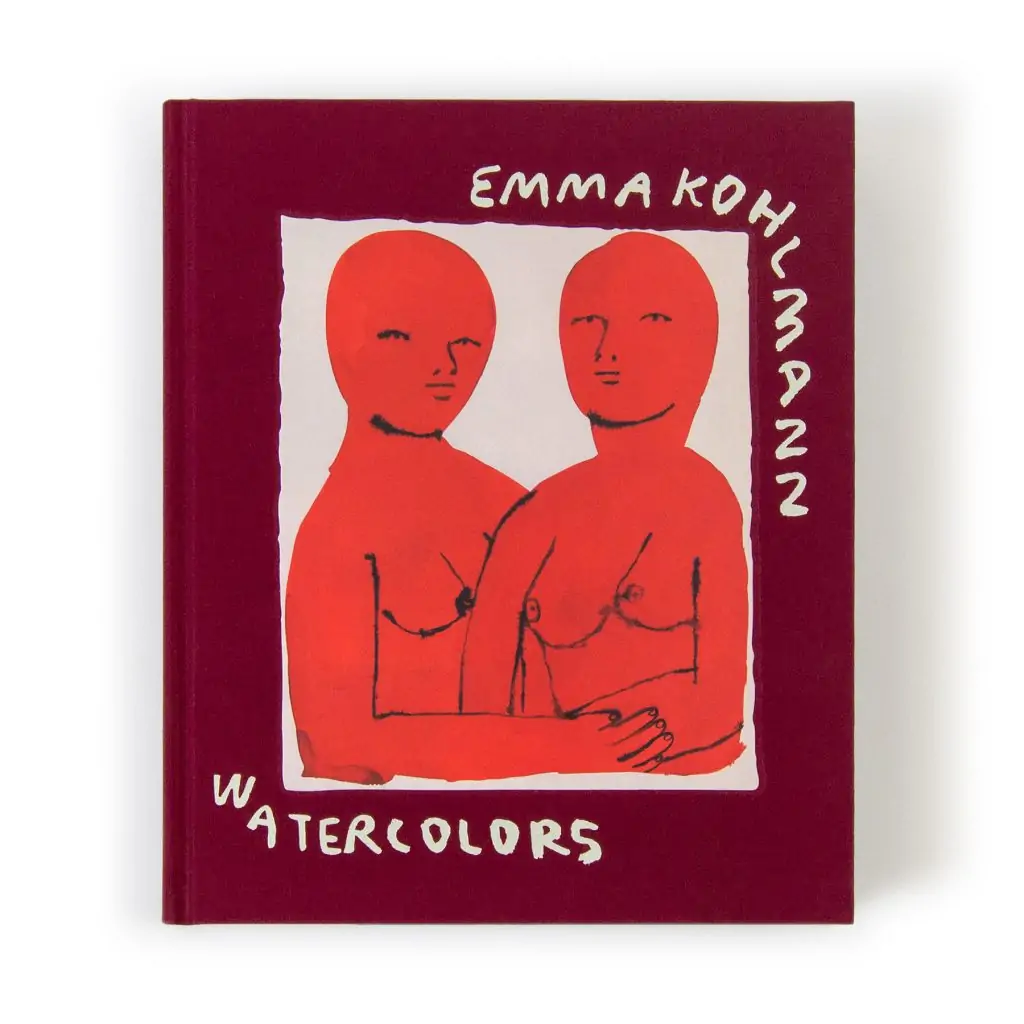

Over the past decade, Kohlmann has been prolifically creating work. This journey is encapsulated in her first monograph, “Watercolors,” covering her work from 2011 to 2021. We recently had the opportunity to speak with Kohlmann following the release of her new book, “Watercolors,” delving into her inspirations, practice, and more.

Emma Kohlmann: Watercolors is available to purchase from Anthology Editions

Hi Emma, thanks for joining us. Can you share your journey into the arts, highlighting key experiences or influences in your early life that led you to pursue a career as an artist?

Emma Kohlmann: Ever since I was a small child, I have been fascinated by the idea of using images to represent a feeling or a message. I hated writing papers or doing homework, but I always felt most comfortable completing school art assignments. I spent a lot of time in my sketchbooks; I was constantly drawing or collaging into them. I think a key experience was being able to go to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City; it gave me references and inspiration as to who an artist could be or what they could do. My parents always brought my sister and me to museums and free cultural events around the City; it encouraged me to feel confident in my own artistic interests and growing relationship towards art.

My Grandmother always had a collection of art and art books in her home. I was and still am intrigued by the art on her walls and find new things to learn from the same pieces that have been hanging on her walls for over fifty years.

After I graduated college, I felt extremely uncertain of what I wanted to do with my life. I set projects for myself to complete and eventually share. Zine making became a way to keep up with a studio practice that felt fleeting due to the time I spent at my service industry job. I really didn’t feel like I was part of a community until I pushed myself out of my own bubble.

Each one was focused on a specific topic like: seasons, a disembodied voice, or being broken hearted on Valentine’s day. I would post images on my Tumblr account and get addresses from people I followed. The materials for each zine varied, from pen and ink drawings, to photocopies of drawings and collages of the drawings. I made over thirty zines from 2013-2016.

Thanks to the very talented artist, Heather Benjamin, who I had known to participate in the Printed Matter New York Art Book Fair and encouraged me to sign-up. Through tabling at this fair, I was able to meet and make friends with people who inspired me and pushed my practice foward. Without Printed Matter, I don’t think I would be the same artist.

Your practice, involving watercolours and inks, often features abstract, sensually charged figures that challenge traditional gender and sexuality norms. Could you discuss the nuances of your practice, your creative approach, and your sources of inspiration?

Emma Kohlmann: My entire series of watercolors started when I was attending my last year of Hampshire College (2010-2011). I didn’t major in art as an undergraduate. I had a lot of other interests and I wanted to explore them. I studied post-colonial theory, aesthetics and philosophy. I have never been an academic; I just like learning to dive into different kinds of topics. I did end up incorporating my art practice into my final thesis.

Part of my inspiration was to make watercolors as a response to the westernized ideas around beauty standards and sexuality I was learning about. I was reading Julia Kristeva’s Powers of Horror, Luce Irigaray This Sex Which Is Not One, and George Batille’s Visions of Excess. I wanted to make work that was critical of what humanity celebrated around figuration, and dismantling whatever that was. Abstraction became a way to illuminate aspects of the figure that felt heavy or disposable. I thought that the blurriness of sumi ink made these pieces feel unstable, on the verge of being simultaneously scary, horrific and beautiful. I was fascinated by the tension between creation and destruction. This series of work really carried me through different iterations of these ideas for years.

Expanding on this, how do you balance form and content in your work, especially when using abstraction to explore complex themes like sexuality and gender politics?

Emma Kohlmann: I came to make abstract work naturally. I don’t really relate to work that is overly literal. I like to discover meaning without the artist instructing me what I am looking at. I think these complex themes were hard to dissect. I think all art is inherently political whether or not the artist intends to make work about it. Making these watercolors was a way to process them. Thematically taboo topics were interesting to me, because I wanted to dig deeper.

I thought about the reclamation of sexuality, using the body as a vehicle to do weird and fantastical things. Musa Mayer ( Philip Guston’s daughter and head of the Guston Foundation) spoke about how her father was asked what a certain symbol meant in a painting, like a teapot or iron; he would say that he was just as mystified by the symbol’s meaning. There was no exact reason why he painted these things; it was rooted in his own subconscious. I can relate to thinking, a lot of the work I had been making in the past was not as focused around my own unconsciousness. Later it became more of a realization.

You’ve talked about deconstructing and reinventing sexual desire in your art. Could you explain how you visually achieve this? What role does abstraction play in this reinvention?

Emma Kohlmann: Abstraction was the way for me to corrupt the traditional tropes of sexual desire. When I started working in color specifically in red, I felt moved by the tactile sensations and emotional responses that came from the color itself.

The murkiness of watercolor makes it possible to fragment or distort images. I think this process breaks down the overall idea of what an image represents. There is an ambiguity between what is reality versus what is fantasy. I think this is more of a bigger topic of how there are complexities in all human experience and it becomes a mirror or inverse of that.

Additionally, you’ve mentioned the unpredictable nature of working with watercolours and inks, particularly their interaction with various paper textures. Could you talk more about your process of selecting materials and how you decide which mediums and surfaces best express a particular idea or theme?

Emma Kohlmann: Watercolor is unpredictable because you have to work quickly. There is a rapidness and elasticity within it too. You can stretch color over paper with just water. It’s kinda magical. There is a sensitivity in all of the materiality. Even just handling the paper, you can see fingerprints and marks below the surface.

I am by no means careful, I just notice when things happen that are unintentional. Each stroke is picked up on paper. You can see lines or mistakes if you are not fast enough. I like the mistakes sometimes but retracing your outlines it can be hard to replicate. The way I work feels like I am carving through the page. It feels sculptural. I don’t like the texture of watercolor paper. I prefer hot pressed paper, I like how it is flat and keeps the boldness of color.

I feel like you lose a lot from watercolor paper, it is meant to be absorbent, thus makes things less bold. I use sumi ink to reveal details in the watercolor. I don’t really know how I discovered combining the two. I worked only in sumi ink for years, and slowly graduated into different colors like crimson red, slate blue, and forest green. I wasn’t conscious of this, it felt like the natural progression. I felt like I “mastered” using sumi ink, now I can play with colors.

I was actually really afraid to venture into color. It felt like more of a statement, how would I know what colors to even use. Color represents things symbolically that the viewer cannot unsee. It felt like a big step for me. I think there is an immediacy with watercolors, you can travel most places with your studio, and that is why I have such a collection of work. I was able to work on the go. It made it easier to keep my practice going even when I was away on vacation. I also did not have a studio for the longest time because of this. I would work in porches or outside.

Your approach to depicting nudes challenges the traditional male gaze. Can you discuss how you reimagine the nude form to empower rather than objectify? What impact do you think this has on the viewer’s experience?

Emma Kohlmann: I have always approached my work with subversion. Studying the Western canon of art history, the muse has always been presumed female. My work has always been driven by a gender neutral subject. I have always been fascinated by androgyny, and how it has historically been portrayed. Specifically in alchemy, androgyny is depicted symbolically through various images. These representations illustrate the integration and balance of masculine and feminine energies within the individual or within the alchemical process of transformation and spiritual enlightenment.

Building on that, you’ve spoken about moving beyond the male-dominated Western canon and being influenced by writers like Audre Lorde. How do these literary influences intersect with your visual art? Do you view your work as a dialogue with these texts?

Emma Kohlmann: As an artist, my work is deeply influenced by a wide range of literary voices, including writers like Audre Lorde, who have challenged and reshaped dominant narratives around identity, power, and representation. I have also been deeply inspired by poetry, poets such as Anne Sexton, June Jordan, and Diane Wakoski. These literary influences intersect with my visual art in myriad ways, informing not only the content and themes of my work but also its conceptual underpinnings and formal elements. I see my work as a reflection of what I read and interpret.

Image courtesy of Emma Kohlmann

You’ve just released Watercolors, your first book that presents a broad spectrum of your artistic journey from 2011 to 2021. Could you share the journey behind its creation, the preparation process, and the book’s essence?

Emma Kohlmann: Watercolors is my first book that feels substantial. I have been self-publishing my own work for the past ten years. It was a process of letting go of my own preconceived notions of what my own “monograph” would look like. I am very indecisive when it comes to these things. I have no idea if my art were a person, would it still be me, let alone it living in a book? Anthology approached me three years ago about working on this project.

Part of the reason why it took so long was because it took time to sort through tons of work from the last ten years that I scanned and archived myself. I am organized and disorganized at the sametime. I used these scans as references to continue making work; I really loved being able to refer back to these scans and see the changes I made. It was part of my own studio practice to go to the library and use their oversized scanner. I would bring stacks at a time and spend days scanning work. I still haven’t really organized these digital files in a more efficient way. Because of all of these scans the book was made. I was so fortunate to have worked with Mark Iosifescu and Jesse Pollock as editors, they gave me feedback that was really helpful and opened my mind to different ways of laying and organizing the work.

How does ‘Watercolors’ reflect your artistic expression and growth as an artist over this decade?

Emma Kohlmann: This work has been something that I have neglected in the past several years. I have been experimenting more with oils and acrylic painting. I am still and always will be someone who works on paper. But it got tiring after a while. I like pushing myself. Having a book that reflects back the past ten years can be an alarming thing. It’s like I can’t believe I made these things. It makes me want to dive back in and work on something new and fresh. I feel like the work I make now is coming from a different place. I am still wrestling with the same themes, but the mode and materials of expressing them has shifted.

(Credit: Annabell Charlotte Kohlmann)

Looking forward, how do you envision the evolution of your practice? Are there particular themes, techniques, or collaborations you’re excited to explore?

Emma Kohlmann: I would like to think that I am unafraid to try new things. All I can do is keep going. I am excited to get back into making ceramics. Working in three dimensions is a new and problematic thing for my practice. I think it’s something i hope to keep working at.

Lastly, could you share your art philosophy? How do you perceive and explain the fundamental importance of art in your life and career?

Emma Kohlmann: It’s not my own, but I always come back to it. In a letter that Sol Lewitt wrote to Eva Hesse, JUST DO.

©2024 Emma Kohlmann