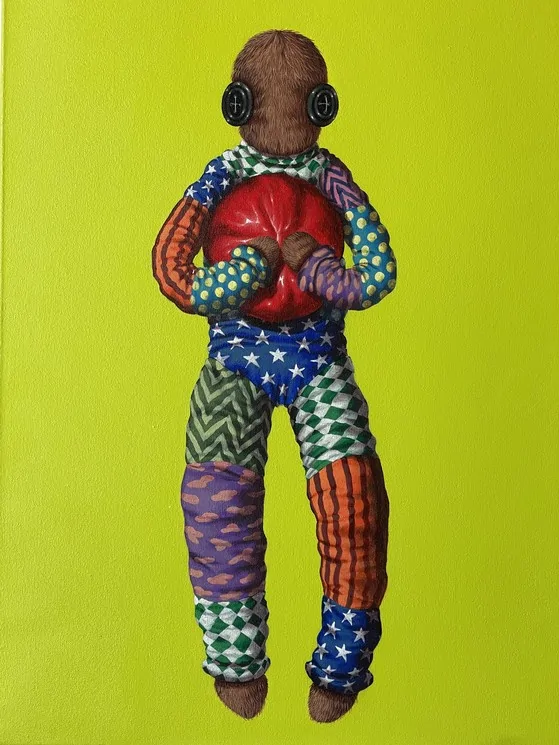

Balinese artist Suanjaya Kencut transforms childhood play and cultural memory into button-eyed dolls that probe innocence, fragility and identity.

In Suanjaya Kencut’s canvases, it is the dolls who speak. They gaze out with button eyes—mute, unblinking, strangely tender, plush as though you could lift them from the surface and hold them close. They carry stories stitched from Balinese myth, childhood play, and the frictions of modern life. At once innocent and unsettling, they feel older than their toy-like forms suggest, as if burdened with secrets their button eyes will never let slip.

It is hard not to be drawn to them. Kencut’s painted dolls are lush with colour and detail, radiating a kind of awe; so vivid they almost seem real to the touch. Perhaps I have already said that, but the urge to repeat it is difficult to resist.

Courtesy of the artist

To me, the button becomes a symbol of sincerity without pretension. It does not display the “soul” directly, but instead allows us to see optimism and vulnerability in a more subtle way

Suanjaya Kencut

Raised in Bali and trained in Yogyakarta, Kencut calls his philosophy simple: life is like a doll. It sounds almost childlike, but his paintings stretch the statement into allegory. Dolls can be vessels, masks, mirrors. They absorb meaning and emotion, yet never quite reveal their own. In this way, his figures become avatars of contemporary existence—fragmented, performative, yet stubbornly human.

Much of this imagery is rooted in memory. The saturated spectacle of Barong performances, the looming presence of ceremonial puppets, and the dense repetitions of temple ornamentation all seep into his visual language.

Later, fashion and textiles added new layers, fusing tradition with contemporary sensibilities. The eyes, cold and uniform, operate as symbols of the subconscious—a place where emotions and identities are stored beneath carefully constructed surfaces. His compositions, often fractal in rhythm, recall both the ornamental repetitions of Bali and the endless cycles of human life.

This month at New York’s GR Gallery, Kencut joins FREAKS, a group exhibition that borrows its title from Tod Browning’s 1932 cult classic. The artist unveils a new series in which his signature dolls are fragmented, multiplied and arranged in layered patterns—abstractions that carry a strange allure, at once unsettling and irresistible. Sharing the space with Kazy Chan and Satoru Koizumi, Kencut works in a vocabulary of tenderness and unease, a balance that has long defined his practice. The pieces hum with contradictions: the beauty of human imperfection, innocence refracted through the uncanny—and this is where Kencut’s work finds its charge.

In the end, Kencut’s dolls are not an escape but a mirror. Stitched and silent, they hold contradictions we carry in ourselves—fragility and resilience, innocence and unease. They remind us that identity is never seamless but something pieced together, broken and mended, always in motion. We are all, in one way or another, stitched together.

100cm x 80cm,

Acrylic on Canvas, 2025

Courtesy of the artist

‘FREAKS’ brings together three distinct yet complementary voices — yours alongside Kazy Chan and Satoru Koizumi. How do you see your button-eyed figures conversing with their visions, and what do you hope emerges from the interplay of your works in a shared space?

Suanjaya Kencut: In the exhibition FREAKS, I present a series of button-eyed figures as an exploration of fragmented and complex identities. The coldness of the button eyes symbolises the subconscious — a place where emotions and identities are stored beneath surfaces that may appear uniform.

Through fractal compositions with repeating patterns and fragmented, doll-like forms, the works reflect the cycles of life, eternity, and the human duality between order and chaos. My practice invites viewers to re-examine reality and identity, which so often feel fractured.

Together with the vibrant energy of Kazy Chan and the surreal tenderness of Satoru Koizumi, a harmonious visual dialogue emerges — celebrating the diversity of identity and the complexity of modern human emotion. I hope these works create a space where the so-called “freaks” can feel empowered and discover beauty within their own existence.

The exhibition references Tod Browning’s 1932 cult film, which sits on the knife’s edge of tenderness and unease. How did this thematic framing resonate with your own exploration of innocence, vulnerability, and optimism through the button-eyed dolls?

Suanjaya Kencut: For me, the film Freaks has always been fascinating because it moves between tenderness and discomfort, presenting a fragile world that is nonetheless full of vitality. That sensibility is very close to what I explore in Fragmentasi. The button-eyed figures I create serve as metaphors for identities that often feel fractured — like fractal fragments that endlessly repeat, vibrant in colour yet carrying a sense of fragility.

Through repetition and the fractal nature of forms that can expand or contract without losing their essence, I want to invite the audience to see that human life also unfolds in cycles: chaotic, yet always searching for order. The optimism in my work does not come from naïve innocence, but from the courage to seek harmony amid uncertainty.

As in Freaks, there is a tension between innocence and strangeness — and it is within that tension that my dolls find their meaning. They are not merely symbols of alienation, but mirrors of how we perceive reality: fragmented, layered, yet still holding onto the hope of connection.

Painting : acrylic

31.3 x 23.8 x 1 inch

Courtesy of the artist

The human eye is often described as the “window to the soul,” yet you deliberately replace it with buttons. Do you see this as an act of withholding, or as a way of offering a different kind of vision — one rooted in sincerity and optimism rather than exposure?

Suanjaya Kencut: For me, replacing eyes with buttons is not simply an act of concealment, but a way of offering an alternative kind of vision. Eyes are often regarded as windows to the soul, full of expression and depth, yet in my work they are transformed into something simple, plain, even repetitive. This creates a space of ambiguity: as if something is hidden while at the same time revealing another kind of honesty — not through individual gazes, but through patterns, colours, and the overall composition.

To me, the button becomes a symbol of sincerity without pretension. It does not display the “soul” directly, but instead allows us to see optimism and vulnerability in a more subtle way. In this sense, the dolls are not merely isolated figures, but representations of how human identity is formed: fragmented, layered, sometimes concealed, yet always holding hope for connection and meaning beneath it all.

Your dolls carry a childlike innocence but also a profound social critique. How do you balance that duality — keeping the work playful and open, yet weighted with reflection on human struggles and complexities?

Suanjaya Kencut: For me, the button-eyed figures are not intended as fixed representations of either children or adults. Rather, I aim to create a fluid space in which viewers can interpret them from their own perspectives. Some may perceive innocence, while others may recognise reflections of vulnerability or the complexities of being human.

The bright colours and playful patterns serve as a visual language that invites closeness, yet behind them lies a deeper layer of meaning. I believe it is this balance between openness and reflection that allows the works to move freely, without binding the audience to a single interpretation.

Painting : acrylic

41 x 35 x 1 inch

Courtesy of the artist

Your works weave together Balinese storytelling traditions with installation-based strategies and contemporary aesthetics. How do you navigate that balance — honouring cultural memory while inventing new, modern forms of experience for audiences?

Suanjaya Kencut: Since childhood, I have been surrounded by the powerful visual and spiritual experiences of Bali. The Barong performances, giant puppets in traditional ceremonies, and temple ornaments rich in repetition and vibrant colours — all of these became imprinted in my subconscious. Without realising it, those memories laid the foundation for the doll characters in my work: figures born from a fusion of ritual, symbolism, and traditional aesthetics.

Over time, I have combined these experiences with my fascination for the modern fashion world, which introduced me to design, textiles, and contemporary sensibilities. From this intersection, the button-eyed dolls emerged: figures that move between cultural memory and today’s visual language. I want to create works that remain playful and approachable, yet carry within them deeper reflections on identity, vulnerability, and the ways in which humans narrate themselves.

In Bali, art has always been a vessel for community and spiritual narratives. Do you see your dolls as continuing that lineage — acting as mediators between personal experience and collective identity?

Suanjaya Kencut: For me, personal experience and collective identity cannot be separated. Since childhood, I have lived within the Balinese tradition, where art is woven into rituals, ceremonies, and daily life. This has shaped my subconscious — teaching me that symbols, colours, and figures are not only visually compelling but also serve as bridges between people, community, and spiritual values.

The button-eyed dolls I create are rooted in personal experience, yet I also want them to speak to shared experiences. They become open spaces, ready to be filled with the emotions and interpretations of viewers, functioning as mediators between my own stories and a collective identity that continues to evolve.

Acrylic on canvas

140 x 200 cm

55 1/8 x 78 3/4 inches

Courtesy of the artist

You’ve noted that these button-eyed figures create a space of honesty, free from lies and negativity. Do you think audiences, particularly those outside of your cultural context, are ready to embrace that vision — or do they read the works through their own filters of nostalgia and unease?

Suanjaya Kencut: I believe every audience, whether from my culture or beyond, will bring their own experiences and perceptions when encountering the work. That is natural—and even essential—because I never want the button-eyed figures to be bound to a single fixed meaning. I present them without expression so they can serve as an open space, ready to be filled with the feelings and imagination of the viewer.

Some may read them as nostalgia, others may sense unease, but for me that is part of the dialogue between the work and the audience. What matters most is that the work continues to carry its original energy: honesty, sincerity, and the colors drawn from my lived experiences in Bali—from ceremonial traditions, the repetitive patterns of temple ornaments, to the creative habits that have been part of my life since childhood.

I want these dolls to act as mediators: born from personal experience yet able to touch collective identity. If audiences from outside my culture interpret the works through their own filters, that only shows the work is open to multiple readings—and within that openness, they may discover a shared point of honesty.

The dolls often feel suspended between being toys and being witnesses. Do you imagine them as guardians of memory, or as mirrors of what we hide in ourselves?

Suanjaya Kencut: For me, the dolls can be both at once. They are guardians of memory, born from childhood experiences and the visual traditions of Bali that have unconsciously shaped my way of seeing form, color, and repetition. Those memories are preserved within the button-eyed figures I create.

At the same time, I also see them as mirrors. With their blank, expressionless gaze, the dolls absorb what viewers bring before them—things that may be hidden, fragile, or difficult to express. In this way, they exist between two roles: keeping personal and collective memory, while also reflecting the inner aspects of ourselves that we often keep concealed.

Painted resin and metal

12 1/2 × 8 × 7 1/2 in | 31.8 × 20.3 × 19.1 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Your practice has expanded from flat, illustrative references to immersive fabric installations. Where do you see the dolls evolving next — will they continue to grow as companions in larger, more experiential environments, or shift into new forms altogether?

Suanjaya Kencut: I see these dolls as characters that continue to live and evolve alongside my journey as an artist. At first, they appeared on flat canvases, carrying layers of color, repetition, and patterns rooted in visual memory. Gradually, they expanded into space — through three-dimensional experiments — allowing viewers to step in and feel their presence directly.

Yet, my work is not only about memories of the past, but also about the experiences I encounter around me, including how I interpret social relationships and togetherness. In several series, the dolls become a medium for contemplating encounters, differences in character, and the importance of support from those closest to us.

For me, they are not rigid forms, but open vessels that can adapt to different mediums, contexts, and the flow of lived experiences. Looking ahead, I imagine they will continue to grow as companions in more immersive spaces, inviting viewers into both physical and emotional encounters. But I am also open to the possibility of them transforming into entirely new forms, because the essence of these dolls lies not only in their shape, but in the values they carry — honesty, vulnerability, social experience, and reflections on what it means to be human.

At its core, what does it mean to you to be an artist? Beyond the objects you create, how does art shape the way you live, reflect, and move through the world?

Suanjaya Kencut: For me, being an artist is not only about producing works, but about how art itself becomes a way of understanding and living life. Growing up surrounded by traditions, art, and spirituality, I unconsciously absorbed creativity as part of my everyday existence. The creative process is not merely a studio practice, but also a medium of reflection, contemplation, and even meditation — shaping how I see myself and others.

Art makes me more sensitive to memories, experiences, and the social realities around me. At times it emerges as a record of the past; at other times as a response to the events and relationships I encounter today. In this sense, art is not simply an object or a finished work displayed on a wall or in a gallery, but a way of living — a way of continuously learning, being honest with myself, and connecting with others through deeper layers of experience.

© 2025 Suanjaya Kencut