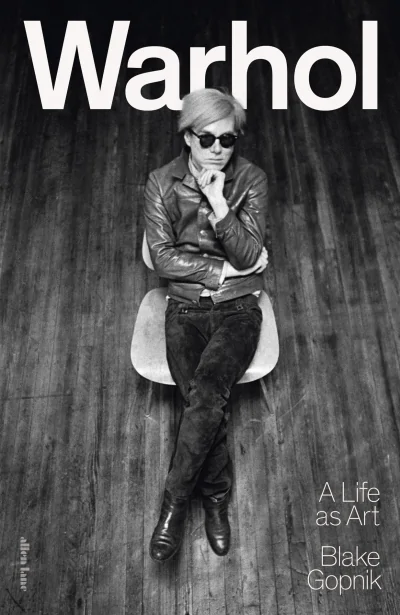

A respected figure in the field, critic and author Blake Gopnik approaches contemporary art with a zeal that strips away pretence to unravel the complexities of art. A scholar and provocateur by nature, Gopnik brings sharp analytical commentary to writing about the arts, combining a reverence for the past with a keen appetite for the new and uncharted, captivating readers with his candid, conversational style.

When you’re an art critic, you end up reviewing a lot of Andy Warhol’s shows inevitably because there are shows everywhere all the time. And I realised that he was a genuinely great artist, even better than people realised.

Blake Gopnik

Born in 1963 in Philadelphia, Gopnik grew up in Montreal’s Habitat 67, an iconic vision of brutalist living, with his early education shaped by a bilingual French foundation at Académie Michèle-Provost. His academic path led him to McGill University, where he earned honours in medieval studies before undertaking a doctorate at Oxford, exploring Renaissance realism and the philosophy of representation.

Before transitioning to journalism, Gopnik’s career in art criticism spanned Canada and included roles as chief art critic at The Washington Post, followed by contributing critic at The New York Times. Since 2011, Gopnik has anointed the artistic mecca New York as home.

Lauded as the definitive authority on all things Warhol, Gopnik is celebrated for his comprehensive 2020 biography, Warhol: A Life as Art. Gopnik pens a must-read, lucid chronology of Warhol’s journey, revealing the intricacies of an artist who changed the art world, painting a portrait as complex and captivating as Warhol himself.

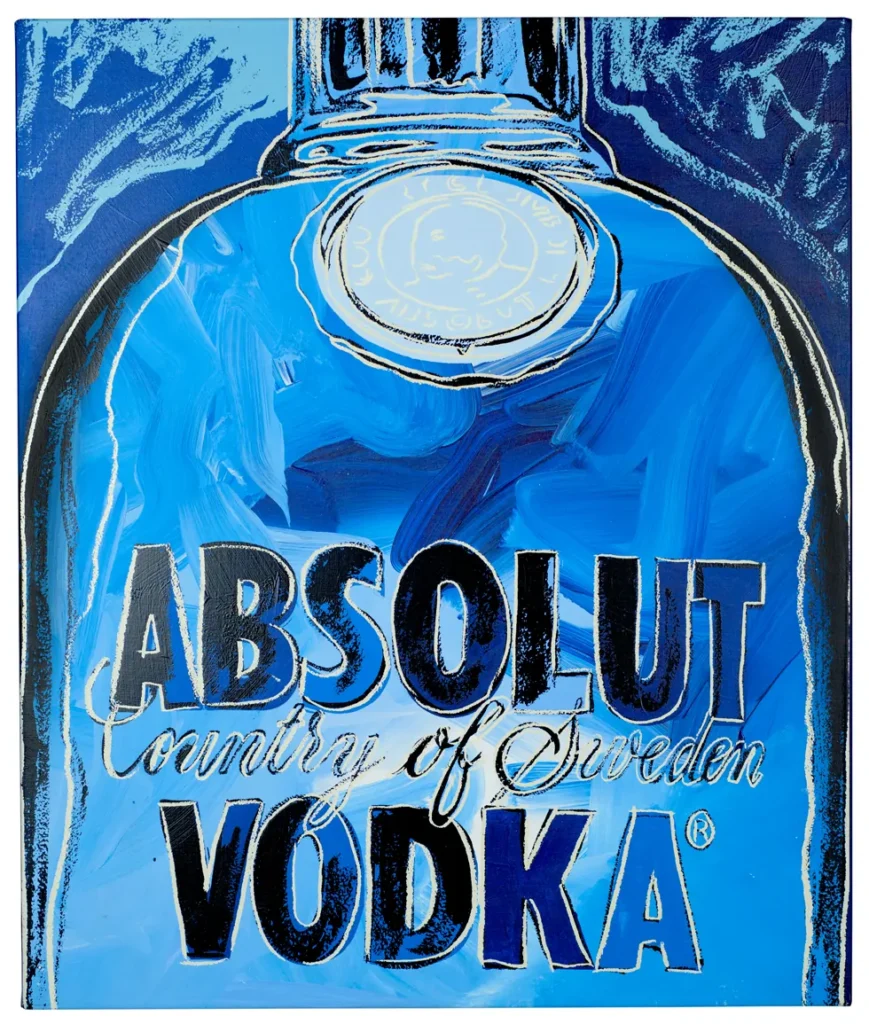

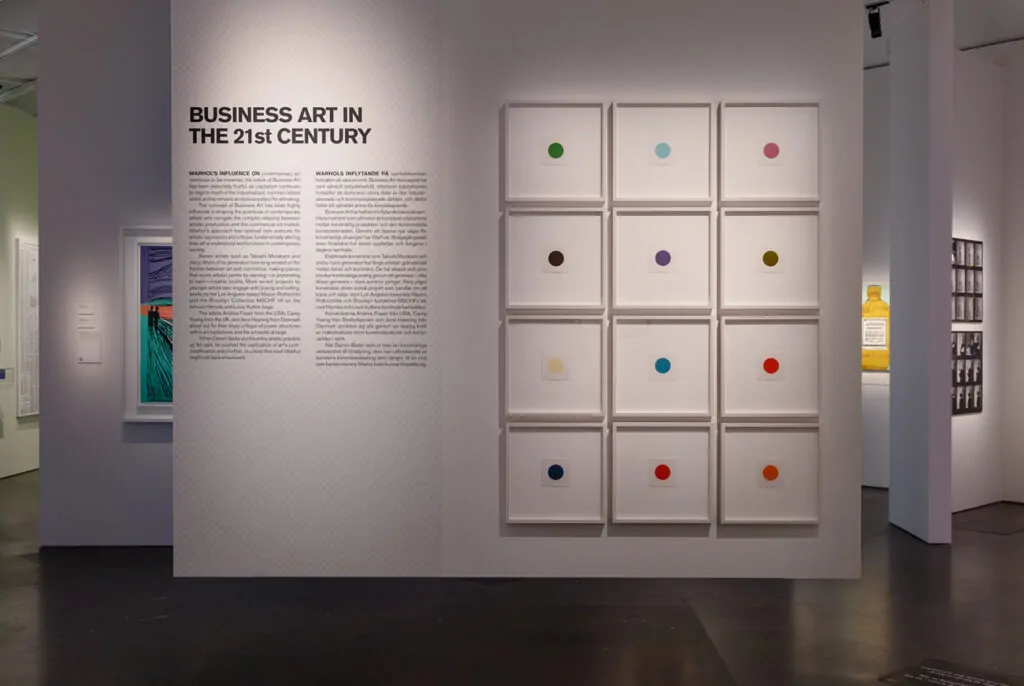

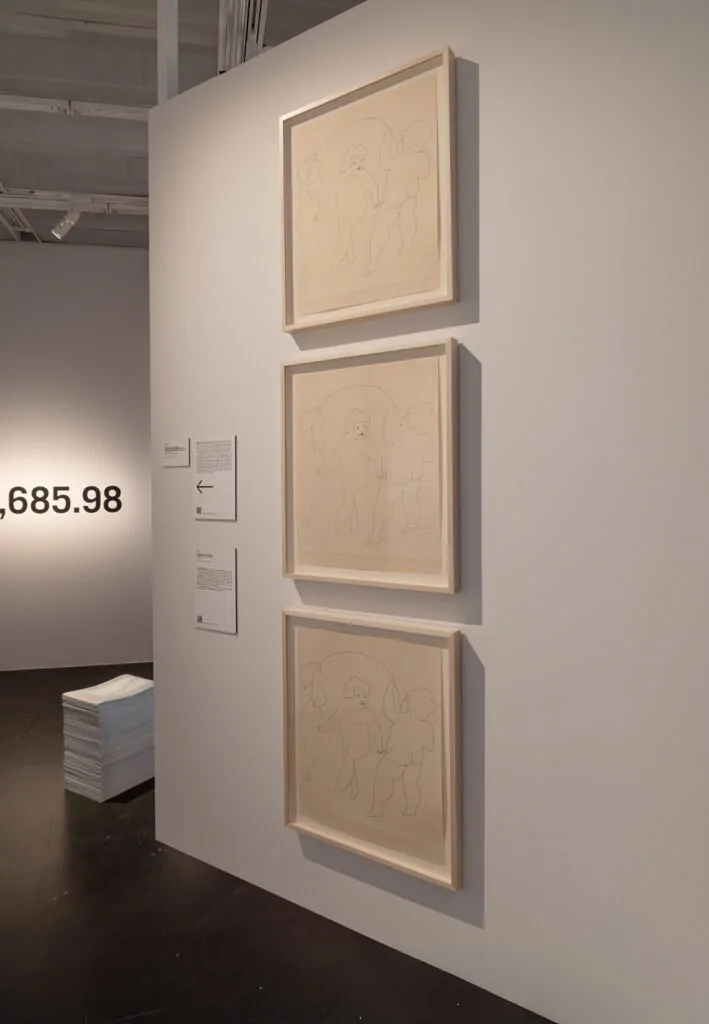

In Gopnik’s first curatorial project at Stockholm’s Spritmuseum, Money on the Wall: Andy Warhol, he focuses on Warhol’s concept of “Business Art,” as Warhol described it, “the step that comes after art.” Gopnik curates works from over 15 pioneering artists alongside Warhol’s own pieces. The exhibition also features the previously lost Warhol Absolut Blue painting. I had the opportunity to sit down with Gopnik to learn more about his work and his curatorial approach to Warhol’s idea of Business Art.

Good afternoon, Blake. How are you doing? Could you start by giving us a little background on how you got into the arts and your journey?

Blake Gopnik: Yeah, kind of complicated. I actually began as an academic, studying 10th century Italy. I was a medieval scholar. And then went to museum and fell in love with art basically. It changed my field as an academic. I became an art historian and eventually kind of an accident became an art critic.

By Blake Gopnik

© Blake Gopnik

When you’re an art critic, you end up reviewing a lot of Andy Warhol’s shows inevitably because there are shows everywhere all the time. I realised that he was a genuinely great artist, even better than people realised, which meant that when the time came to write a biography of Andy Warhol, someone had to write a serious comprehensive biography of Andy Warhol, I decided and some other people decided that I was the right person to do it.

So I spent eight years of my life pretty much morning until night studying Andy Warhol, looking at his archive. I mean he kept every receipt for every meal he ever had, every movie that he went to, we have the stubs. So we know everything about his life and what I have to do is take this huge amount of information and collapse it into one book that was only a thousand pages long.

So I published that. And now, I’m curating my first show here in Stockholm about Andy Warhol. I’m very excited to be doing it for Spritmuseum in Stockholm. I’ve never been to Stockholm before. I’ve never been to this museum in fact before and I’m completely in love with my own show, if I may say so.

2 original paintings, 141×115 cm.

© 2024 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

How does the rediscovery of Absolut Warhol (The Blue Version) deepen our understanding of Warhol’s commercial collaborations?

Blake Gopnik: One of the interesting things about the fact that they discovered a second Absolut painting is that it connects his work in the 1980s to his very earliest work as a commercial illustrator because he was famous for offering clients several versions of anything he did. So in the ‘50s already, he realized that he could move ahead of other illustrators by being more client-friendly.

So it turns out—I guess we didn’t really know this—that he had done the same thing for Absolut, giving them the so-called black version and the blue version. The difference is, by 1985, he was one of the most famous artists in the entire world and had a history since the early 1960s of making work that was about business but also critical of capitalism and commercialism.

My show here in Stockholm is about this new kind of art he created called Business Art, where the very act of engaging in business, engaging with businesses, became an art supply like oil paint. And when he did this, there was always the possibility—the reality—that he was also critiquing capitalism and consumerism.

So when he comes to do the Absolut bottle, it stands as one of his most important Business Art projects because he made $60,000 doing it, which was a lot of money. It’s a lot of money now, but it was a great deal of money in 1985. And it turns out to be one of the most successful artist-sponsored brands in history. Absolut was already an important brand or starting to be, but when he did the bottle for them, it became a really big deal.

But at the same time, his involvement with Absolut is part of his career as a business artist, which means that inevitably, there’s a sense of critique or concern about capitalism in it. It’s putting capitalism on display and saying, ‘Think about this. Don’t just take it for granted.’

So like all of his best Business Art, it’s business, and it’s art, and it’s art that critiques business at the same time, and that’s what makes it more interesting than your average ad for a product.

2 original paintings, 141×115 cm.

© 2024 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photo credit Art Plugged

In placing Warhol alongside other artists who explore themes of consumption and consumerism, what connections or contrasts between Warhol and contemporary artists do you hope visitors will discover through this exhibition?

Blake Gopnik: I think the one thing they’re going to discover is that Warhol is at the root of a great deal of contemporary art. A lot of contemporary art—good contemporary art—has a complicated relationship with popular culture and consumerism. It doesn’t just celebrate it. It doesn’t—if it’s good art—just sit there and absorb it or even portray it, but questions it at the same time. So Warhol is at the very origin of that.

In our show, we deliberately included, at the very end of it, a bunch of work by 21st-century followers of Warhol, followers of Warhol, business artists, because a lot of what he did—a lot of the confusion of categories that he began—still exists today in the best art. So you don’t know: Are you looking at art? Are you looking at business? Are you looking at critique or celebration? The confusion itself is really the art form. And Warhol is at the root of that.

And the best art today isn’t pre-painting. It’s not an impressive sculpture. It’s something that questions all categories.

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

How does Swedish design and cultural identity, as explored in the Spritmuseum’s rotating exhibitions, provide a unique context for Warhol’s work and its focus on mass production, consumerism, and branding?

Blake Gopnik: From what I know of Sweden—and God knows I’m no expert—Sweden has often had a complicated and interesting relationship with mass production. Sweden has two of the most important consumer brands in the world now, IKEA and H&M, and both of those are companies that aren’t only about making as much money as you can by putting junk out into the world; they take the creative side seriously at the same time as they want to make goods for the average person. And of course, those are issues that were essential to Warhol as well.

So I think this tradition of taking everyday objects seriously, imagining that you can make art based on them, and the interaction between high culture and low culture is an interesting and important one. All of those things that are present, I think, in Swedish attitudes towards consumption and products are there in Warhol as well. Now, Warhol, of course, is a fine artist in part, so he is commenting on them in a way that I think H&M and IKEA don’t quite do. But I think they’re participating in a similar culture of questioning, and I think that’s really interesting.

And not everywhere is quite like that. In America, where I come from, I think we take consumption and products more for granted as being good in their own right. Making money by itself is good even if you’re selling junk. I think in Sweden, they’ve got a more complicated relationship.

One of my favourite works of contemporary art involved an artist called Guy Ben-Ner, who, as his work, took his whole family to IKEA in pajamas, and they all got into bed and pretended they lived there. And apparently, IKEA didn’t know what was happening. So he was filming a video of his kids; they would put on a piece of clothing from IKEA with the tags still hanging, and they would pull the covers up to their necks with the tags on them.

It was just a hilarious video of a family living in IKEA. And then he got kicked out of that IKEA, so he would go from IKEA to IKEA in order to finish his film of a family spending a day living in IKEA. It was beautiful. Yeah, it’s superb.

© 2024 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Do you think there will ever be another Warhol, not in terms of just an outright copy, but an artist who embodies his approach, philosophy, and vision of art?

Blake Gopnik: I’m not sure there will be another Warhol in the sense of embodying the spirit of his art, because of course, he did a damn good job of that. I feel confident that there will be another artistic genius. There have only been, in the history of Western art—and we’re talking about Western art here—a handful of artists as great as Warhol: Michelangelo, Titian, Rembrandt, Goya, Picasso, the very, very few people at that level of genius. There are many artists I love today—many. I should say there are at least 15 artists that I love today. None of them, I think, have risen to that level.

But we just have to wait. We’re in the worst moment I can ever think of for art. There’s so much bad art being made. And people like me and all my friends are always mourning it, and I say, ‘There have been lots of moments like this before.’ 1905 is not the greatest moment in the history of art, and then Picasso comes along a few years later. So you just can’t predict. If I could predict what was going to come next, I’d be a great artist and maybe even wealthy. Of course, I can’t, because whatever comes has to be something that we weren’t expecting, or it’s not that important.

Photo Dan Kullberg

Andy Warhol Spritmuseum

Lastly, can you share with us your philosophy of art in terms of your work, life, and curatorial approach?

Blake Gopnik: Yeah. I’d love to answer the question, especially because this is my first time as a curator, and I’ve decided it is impossible. It is so unbelievably hard to take a theme and then find objects, and then get someone to lend you the objects. I mean, every object requires a thousand emails. I can’t believe that people do this every day because I’m about to die from exhaustion, and I did one-hundredth of what the curators at the Spritmuseum did.

I mean, this is a small museum, and they pulled off a giant feat—I mean, all of these loans, these Warhol objects worth insane amounts of money. I will never again curate an exhibition because it is too hard. I just want to be an art critic. I want to write thousand-page books because that’s easier than curating one small exhibition. So that’s my philosophy on curating.

And art just matters more to me than anything else. It’s the ultimate example of doing things for their own sake. If it’s good, it’s doing whatever you think is the most compelling, interesting, and important thing you can possibly do. There’s almost nothing else in life that’s like that. And if you’re being judged correctly, it’s about your ability to do that—your ability to put art before anything else and make the most interesting and important art you can possibly make.

by Andy Warhol” BY MSCHF, 2021

Photo Dan Kullberg

Andy Warhol Spritmuseum

Ideally, make art that contributes something that hasn’t been contributed before. We have a lot of nice oil paintings of people’s faces. We don’t need more of those. And great artists really change everything about the culture, and you’re allowed to do that. It’s the one area where, in an ideal situation, making money shouldn’t matter—unless you’re a business artist like Warhol, where the money is the point.

It really should simply be that you should only be judged on how profoundly you’ve rethought any number of things. It could be rethinking politics. It could be rethinking art. There really is no other activity where that is the goal. So for me, that’s the most exciting thing in the world, and one out of a million artists succeeds. If it’s good, it’s unbelievably exciting.

Money on the Wall: Andy Warhol Curated by Blake Gopnik opens on the 18th of October, 2024 until the 27th of April, 2025 at Spritmuseum, Stockholm

©2024 Blake Gopnik, The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts