Over the past two weeks, the world has mourned the murder of George Floyd, who died at the hands of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin. With his death, the world also mourned–and will continue to mourn–the shooting of 25-year-old Ahmaud Arbery by two armed white men in a South Georgia neighborhood in February, and the March shooting of 26-year-old emergency medical technician Breonna Taylor by Louisville police offers who had clearance for a “no-knock warrant” to enter her home. Arbery was jogging; the Louisville police had the wrong home.

Each of these deaths were reminders of the countless lists of black people who are brutalized by the hyper-aggressive, militarized American police force and the subsequent violent, racist civilians who use their privilege to hunt them. Yet again, these deaths are reminders of the anti-blackness that runs throughout many cultures, countries, and regions in the world. What’s more, these are reminders that while we appropriate black culture, black bodies, black vernacular, and all that is produced and popularized by black people, we continue to witness their dehumanization.

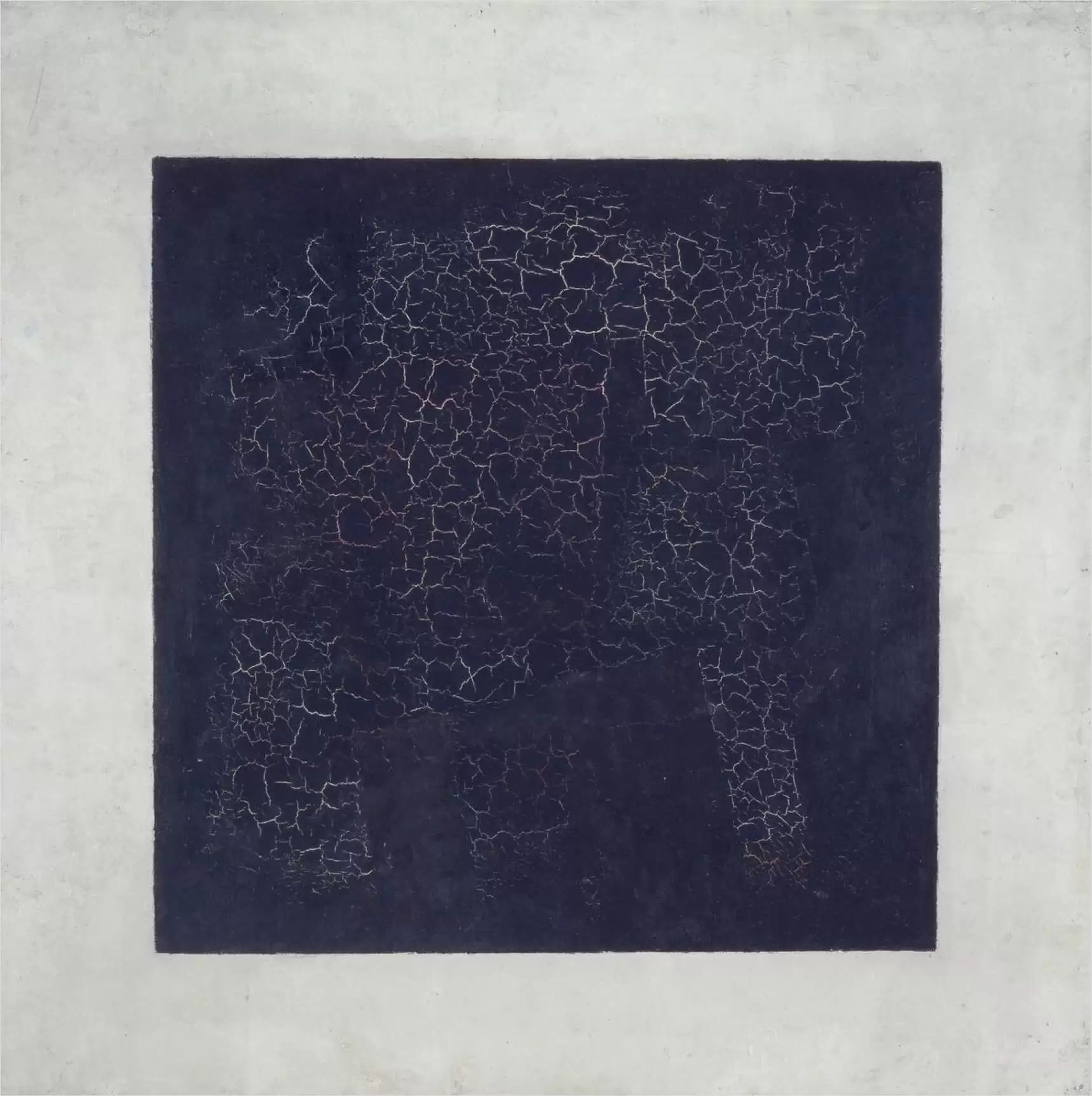

#blackouttuesday

Individuals and organizations alike took to social media to profess their alliance with black communities, human rights groups, and black creators, leading to the Blackout Tuesday trend that went viral on Tuesday, June 2. The trend was created by two black women in the music industry as a way of “intentionally disrupting the work week,” partly because the two women observed how music industry heads profited from black artists without always acknowledging them, failing to properly “empower the black communities that made them disproportionately wealthy.” It asked social media users to post images of black squares, often with the tag #BlackoutTuesday, sparking criticism from those who said the posts were insincere and required minimal effort on the posters’ part.

Blackout Tuesday‘s purpose was meant as a way for social media users to put aside self-promotion, but it quickly became a way for Instagrammers to conveniently align themselves with a sentiment they could otherwise afford to ignore and individuals (this includes celebrities and influencers) and companies or organizations to advertise themselves as supportive allies.

One issue critics of the trend raised is that many social media users posted blackout content using the #BlackLivesMatter tag, obscuring important posts directly associated with aiding protestors. The main issue here, however, is of sincerity and performative allyship; in this case, from the art world. All industries with a public image and social media channels are self-conscious, and that insecurity is amplified by those working and interested in the visual arts.

The pressure to react—to suddenly become that much more supportive to black artists—has some wondering: where were these institutions and art lovers before these deaths occurred? Why the collective mourning now, when those of us calling for the de-colonization of museums, and for discourse on cultural reparations, were seen as extreme in our criticism? As many Twitter and Instagram users noted, the term “looting” derives from British colonization of the Indian subcontinent, and it conveniently ignores the centuries of stolen artifacts at the hands of European imperialists—or, as some call them today, “collectors.”

Some of the same museums that participated in Blackout Tuesday and posted images of black artists featured in their collections also actively participate in the erasure of black creators. The same spaces that represent contemporary black artists are the same spaces that tokenize their black visitors, often reducing them to a checked survey box or demographic statistic. These are the same institutions who pigeonhole black experiences to a constant “struggle,” without properly recognizing black grievances within their own field. The list goes on.

Separate-but-unequal programming,

Judith Wilson

As the late Maurice Berger noted in his article on art museums’ embedded exclusion of non-white artists and arts professionals, “Despite the recent increase in exhibitions devoted to African American art in major museums, these shows rarely address the underlying resistance of the art world to people of color.” Berger references historian Judith Wilson’s term “separate-but-unequal programming,” with “African American shows in February, during Black History Month, white shows the rest of the year.”

Why are leaders in arts communities just now realizing the layers of inaccessibility within their spaces? Putting sentiment into practice, all arts institutions, arts professionals, and enthusiasts have to un-learn the surface-level support that arises during heightened crises.

While they face periodical growing pains of accountability, they must understand that cultural oppression is pervasive and all-encompassing. Genuine recognition involves re-education rather than just fleeting and disposable social media “sharing.” Active exclusion, discrimination, and tokenization can’t be undone with the convenient indulgence in visibility politics: it runs deeper than that.

©2020 Copyright Kazimir Malevich, André Manguba