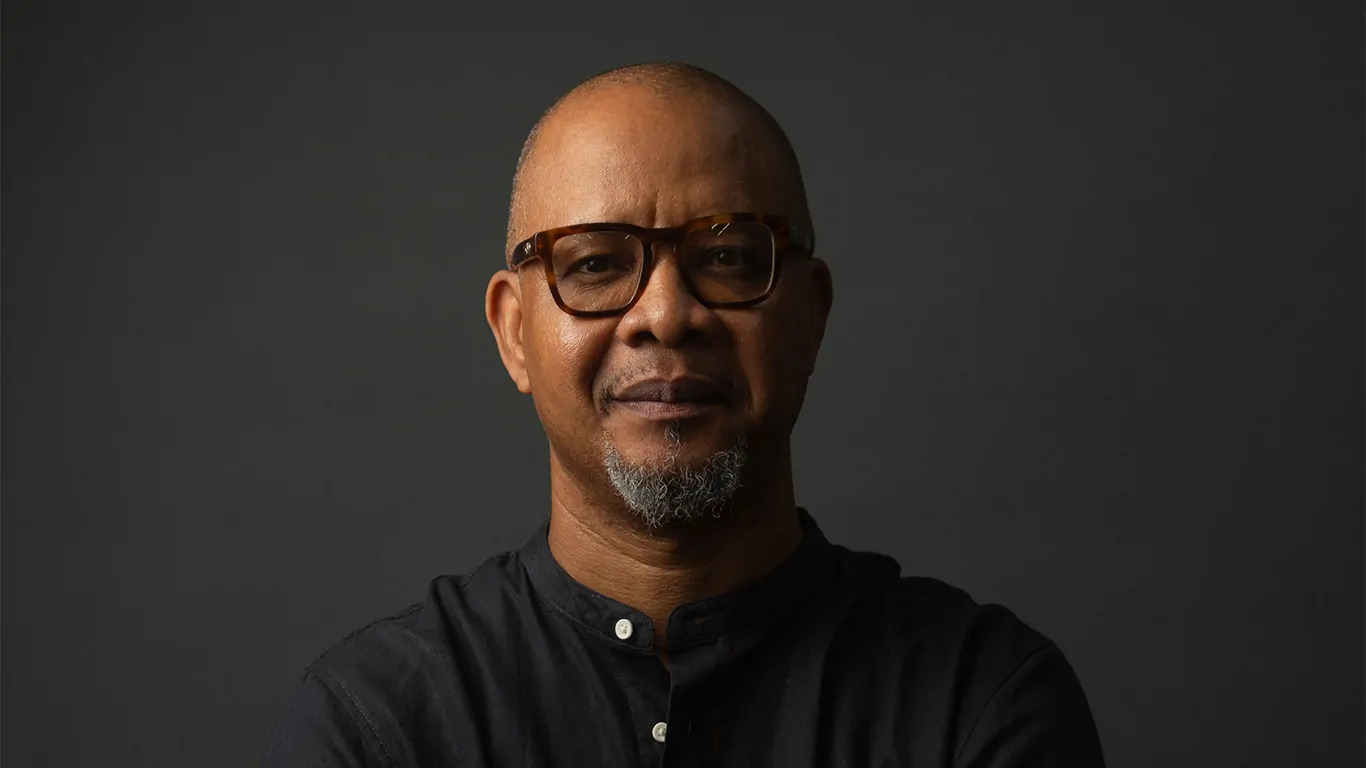

The practice of Nigerian multidisciplinary artist Victor Ehikhamenor does not whisper—it roars, pulsating with quiet thunder, a resolve of history revisited, identity reclaimed, and memory-defying erasure.

Ehikhamenor is celebrated for his intricate explorations of Nigerian cultural heritage, the global African diaspora, and the enduring scars of post-colonialism on the African continent. His work carries both dignified historical weight and contemporary relevance, illuminating what colonial histories sought to erase while drawing from the deep reservoir of Nigeria’s cultural consciousness.

Channeling sacred symbols and devotional textures, Ehikhamenor unearths truths long buried. As the Benin Bronzes reclaim their rightful place in global discussions, his voice emerges alongside them—a vigilant custodian of ancestral narratives, unafraid to confront and question.

His art practice is deeply spiritual, rooted in the indigenous motifs of Edo culture—the cradle of the Benin Bronzes. Yet it goes further, challenging Western constructs that have long contained African power. His bold forms and hypnotic patterns serve as vessels for ancestral spirits while addressing contemporary tensions: colonial baggage, capitalism, and the relentless push for cultural recognition.

Courtesy the artist and MARUANI MERCIER

My work does not centre on colonially minded observers; it’s a conversation to help those who may not know about my culture to better understand us in a contemporary context

Victor Ehikhamenor

The global reckoning surrounding the Benin Bronzes has sharpened the focus on Ehikhamenor’s perspective. Looted during the British Empire’s punitive expedition of 1897, these masterpieces—bronze and brass creations of unparalleled artistry—were torn from their origins and enshrined in European museums as relics of a “vanished” civilization. But the civilization never vanished. It persists in spirit, form, and the artistry of individuals like Ehikhamenor, who make the stolen visible, connecting the past and present.

A potent example is his monumental Still Standing, displayed in London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral. Crafted from 5,000 rosary beads, rhinestones, and bronze statuettes, the 12-foot mixed-media work pays homage to Oba Ovonramwen, the last ruler of Benin before the British incursion.

Hauntingly positioned near a memorial to Admiral Harry Holdsworth Rawson—the architect of the 1897 invasion—the piece transforms the cathedral into a site of confrontation and reflection. Shimmering with layered meaning, a cacophony of Edo spiritual traditions and Catholic iconography underscores the entangled histories of conquest, faith, and resistance.

This work exemplifies the themes and practices that have elevated Ehikhamenor to international prominence. His influence reaches far and wide, with exhibitions spanning Munich, France, New York, and London. His role in the inaugural Nigerian Pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale in 2017 cemented his stature as an artist of international significance.

Now, in his European solo exhibition at Brussels’ MARUANI MERCIER, The Enigma of Time Remembered continues his exploration of culture, heritage, and the African diaspora. This comprehensive showcase celebrates the resilience and spirit of the African identity while highlighting the consequences of colonialism.

An open invitation, Ehikhamenor’s work guides those unfamiliar with his culture toward a richer understanding of its relevance—inviting reflection through its universal themes of resilience and identity.

Yet Ehikhamenor is no prisoner of the past, more a compass connecting the artisan practices of ancient Benin with contemporary custodians. Raised in a small Edo State village, the ceremonial altars, ritualistic imagery, and cultural symbols of Ehikhamenor’s youth infuse his work, transforming into both decoration and repositories of memory, taking on new meanings that sow seeds for the future.

Ehikhamenor reclaims Africa’s place as a cornerstone of contemporary art, not as a relic but as a revelation, solidifying his influence as one of the most impactful artists of his time. We managed to catch up with the artist during his exhibition at MARUANI MERCIER to learn more about his practice, thoughts on Benin and more.

Hi Victor, thank you for joining us. To start, could you share a bit about your journey into the arts? Were there any key moments or influential experiences that inspired you to pursue a career as an artist?

Victor Ehikhamenor: Thank you for the conversation. It’s a bit difficult to condense multiple decades of practice into a few words. In any case, I can’t recall a time when I wasn’t an artist, always making one form of work or another. I started like every other kid, but over time I became a bit obsessed with drawings on any surface I could find. From clean sandy earth to my parents’ and grandparents’ walls in the village. I was surrounded by art everywhere. From local architecture, to shrine walls with ancient iconographies, to installations in commemorative altars and masquerade making and performances during festivals. I consumed it all as a kid, fixating on everything art without even knowing what the word ‘artist’ meant.

I also have an uncle who is in his 90s now. He is one of the early photographers in Benin City and he went to study photography in New York in the early 60s, literally bringing America to my village in suitcases full of images. Growing up, that was a huge influence on image-making for me. He photographed the Oba’s palace from the 50s, a tradition I continued in the 2000s that has eventually morphed into my current body of works dwelling on Benin and African royalty. There is no one particular seminal moment that made me the artist I am today, it’s a combination of multiple experiences along life’s path.

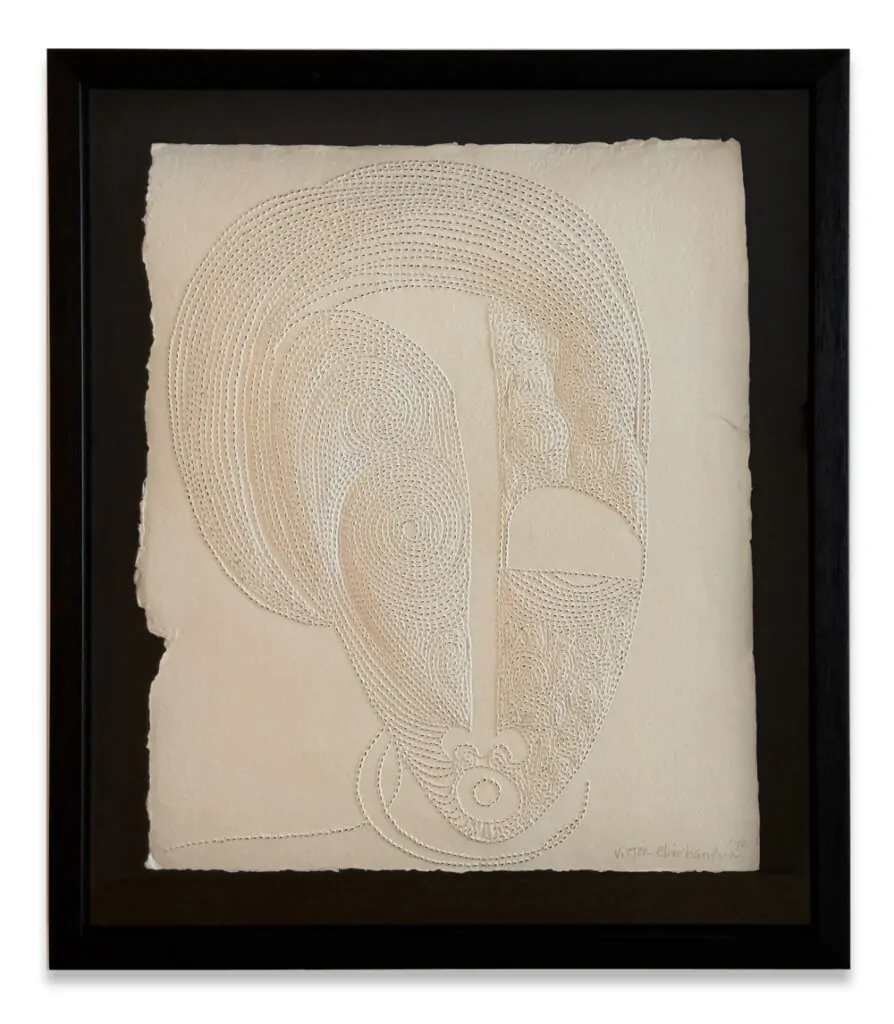

OTUMBA, 2022

signed and dated

perforation on handmade paper

49.5 x 40.6 cm 19 1/2 x 16 in

Courtesy the artist and MARUANI MERCIER

You have a multifaceted approach to art-making that spans sculpture, painting, and installations, exploring themes of culture and heritage, the African diaspora, identity, and colonialism. Could we delve further into your practice, creative process, inspirations, and the themes in your work?

Victor Ehikhamenor: I think what most people see or are experiencing now, is one aspect of my practice, which is the visual art part. As a writer and photographer, multiple things come to play in my art-making. Majority of existing artworks start from literature. It could be a poem, fiction or nonfiction. I approach drawings, paintings or installations in the same way a writer would approach a story or a novel form. What’s the theme, who is the main character, are there other characters, settings, historical antecedents – something along that line.

Courtesy the artist and MARUANI MERCIER

Your work challenges the Western gaze on African art, particularly within the context of repatriation debates and colonialism, often opening a dialogue about the ownership of cultural artifacts, especially through installations referencing the Benin bronzes. As a strong advocate for their repatriation, how do you aim to reframe this narrative through your art, and how does this advocacy influence your creative process while shaping the evolving conversation about cultural restitution in the art world today?

Victor Ehikhamenor: I would say ‘challenge’ is too volatile a word for me to use. Let’s anchor this instead in re-education, re-position of history, which before now has been written from a very lopsided angle. What we, people of Benin Kingdom origin, have been saying dating back to the 1930s, is for our cultural patrimonies, violently yanked from us by the British, to be returned to us because we have greater use for them at home than objects in sterile western museums.

My work is also a continuation of a long-standing tradition of art-making as a form of cultural strengthening in my homeland. My work does not centre on colonially minded observers; it’s a conversation to help those who may not know about my culture to better understand us in a contemporary context. It is also a gentle reminder that the end of colonialism did not put a hard stop on creativity in the continent. I say that because when you go to many Western museums, what they gloat about and tout as African art are mostly blood art, looted, pillaged.

And I always wonder, where are the modernist and contemporary African art to signal continuity and tell a better story like what they do with European classics, modernists and contemporary artists. In any case, contemporary creatives of African descent like me are no longer waiting for others to help tell our stories. We no longer use borrowed tongues to narrate our history – we are telling our stories, one painting at a time, one novel at a time, one installation at a time – so on and so forth.

(photo: Graham Lacdao/St Paul’s Cathedral) © Graham Lacdao, St Paul’s Cathedral

Additionally, themes of displacement and diaspora are central to many of your projects. How do you explore the idea of ‘home’ and identity in your work, especially for African people living in post-colonial contexts?

Victor Ehikhamenor: The strands of displacement and diasporic themes stem from my years in America, where I would say I walked on unstable cultural tall stilts to take another look back home. I can’t help but reference my experiences there. I also started consuming African American literature from the age of 17, when I was admitted to Ambrose Alli University in Edo State to study English and Literature. Having said that, the legs with which I stand at home are not shaky, nor do I ever wonder what my identity is. That’s probably why you will never find me describing my work as a “search for identity”. I know who I am and know the great kingdom, elders and great men and women who raised me. The reinforcement, commemoration, celebration, and self-reflection of our culture and society is what my work embodies.

As a multidisciplinary artist and writer, how do these disciplines inform and complement each other in your approach to storytelling and art-making?

Victor Ehikhamenor: I have actually spoken about this before, they are all interwoven and feed off each other. I read and write literature, which helps in situating my art-making process. When I write, being an artist helps me to see beyond the words I am using. Again, it’s all interwoven – the head and the hair it carries are not strangers to each other, as my elders would say.

Pope XII In Benin Kingdom, 2021

rosary beads, thread and

gemstones on lace textile

approximative size: 180 x 100 x 100 cm

Courtesy the artist and MARUANI MERCIER

Your installations often occupy entire spaces, immersing viewers in intricate patterns and symbols. How do you want audiences to experience these environments, and what emotions or thoughts are you hoping to evoke?

Victor Ehikhamenor: I am not really prescriptive on how my audience should engage with my installations. I always say I have to excite myself with the work as an artist and can only hope others will enjoy it from their own perspective. As kids, we made installations in village that were ephemeral and we would get very excited. If it was good enough, elders would stop to commend and compliment us, but we made it for ourselves first.

I don’t think I have deviated from that mindset. I can only hope that people find something they can connect with, I use familiar, mundane materials to create the enigmas and leave the rest to the rest. Many people wept inside my installation “Do this in memory of us” at Gagosian gallery in London, an exhibition curated by Peju Oshin – I didn’t expect that kind emotional reaction to the work, but a lot of people came out with visibly red eyes because of the story the piece carried.

Cathedral of the Mind, 2023

Rosary beads and thread on lace textile and canvas

502 x 371 cm 197 5/8 x 146 in

Courtesy the artist and MARUANI MERCIER

The intricate patterns in your work often feel meditative and deeply symbolic. Can you talk about how these patterns connect with your personal experiences and cultural identity?

Victor Ehikhamenor: This is the iconography I have been consuming from village architectures and shrines since I was a kid. Over the years I have found my own voice and language to tell my stories. But you can also find similar patterns in carvings and bronze works from the Benin kingdom and its surroundings. Working with the pattern is meditative, and it takes me to places I can’t physically access.

You were one of three artists chosen to represent Nigeria in its first national pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale in 2017, alongside Peju Alatise and Qudus Onikeku. How did this experience shape your perspective on representing Nigerian art in such a globally significant space, and how did it influence your subsequent work?

Victor Ehikhamenor: It was great to finally be part of the inaugural team that represented Nigeria in Venice in 2017. One experience I would say influenced my work was an encounter with a racist landlady in Venice who called my Benin bronze statuettes “fetish”. It helped me realize that colonialism still lives in some Western minds. That experience made me seek a material that would reorient people like her, and that was the beginning of my use of rosaries as a medium.

Courtesy the artist and MARUANI MERCIER

This exhibition, The Enigma of Time Remembered, at MARUANI MERCIER is your first solo showing in Europe, where audiences encounter the cultural depth of your work from a global perspective. How do you envision European audiences interpreting the Nigerian historical and spiritual symbolism embedded in your work?

Victor Ehikhamenor Many Europeans are actually not strangers to Nigerian or any other African community’s historical spiritual symbolism. Our archives, in the form of art-making can be found in many of their museums. However, my work is to reiterate a certain continuum they seem to think doesn’t exist. I envision a reawakening, a realisation that a mask carved out of iroko tree can’t be separated from the essence of that iroko tree. We contemporary artists from the continent, have a very long, unbroken history of art-making, heavily influenced by our past and present. And we also have a voice in global conversations. We know more about those who don’t know anything about us. Hopefully, this is one among many other interventions to engage, not disengage.

In an increasingly globalized art world, how do you ensure that your work remains authentic to Nigerian and African cultural contexts while still being accessible to international audiences?

Defining what is authentically Nigerian or African these days is not a conversation I dwell on. If I think too much about that, I risk boxing myself into a lonely corner. If I want to be inspired by the works of James Baldwin or Gabriel Marcia Marquez, Salman Rushdie, Zadie Smith, Leonardo Drew, Rasheed Johnson or Sam Gilliam, I shouldn’t feel hindered. Does that shift my authenticity as an artist born in Nigeria? I don’t think so. Iron sharpens iron, and we are global now, if I am who I am, my work will reflect and radiate who I am.

Umogun I, 2024

rosary, coral beads, and thread

with bronze statuette on lace textile

170.2 x 116.8 x 7.1 cm 67 x 46 x 2 3/4 in

Courtesy the artist and MARUANI MERCIER

Following on from that, how do you see contemporary African artists redefining or expanding upon these artistic traditions as they engage with a global art audience?

No two artists are actually the same, no matter how closely their practice or work may be. I think everyone will find their path to a fertile land that will grow their crops of creativity and figure out how to prevent weeds from overrunning their farms. Many of us know where we are coming from, and for those who are working in the continent, the community will always provide them with inspiration and influences – be it from the past or present. We are not redefining, we are expanding on our existing knowledge bases.

Rosary beads, thread on lace textile and canvas

30 ft x 15 ft

Courtesy of the artist © Victor Ehikhamenor

Finally, how would you articulate your philosophy of art, and what significance does it hold in shaping your life and career? How has this philosophy developed over the course of your journey?

Victor Ehikhamenor: As we grow older and evolve, our philosophy also grows and evolves. I see the world through the lens of art. That can be beautiful and it can also be very ugly. In any case, I take one day at a time, holding tightly to the railings of art-making and art consumption in its many forms.

©2024 Victor Ehikhamenor