We all wear masks — one for the boss, one for the lover, another for the mirror. Which one tells the truth? Maybe none. Maybe survival means not asking. But the body remembers. That itch under the skin, that line you wish you never said, that night you wished to forget — it lingers. The truth always does, no matter how well we hide it.

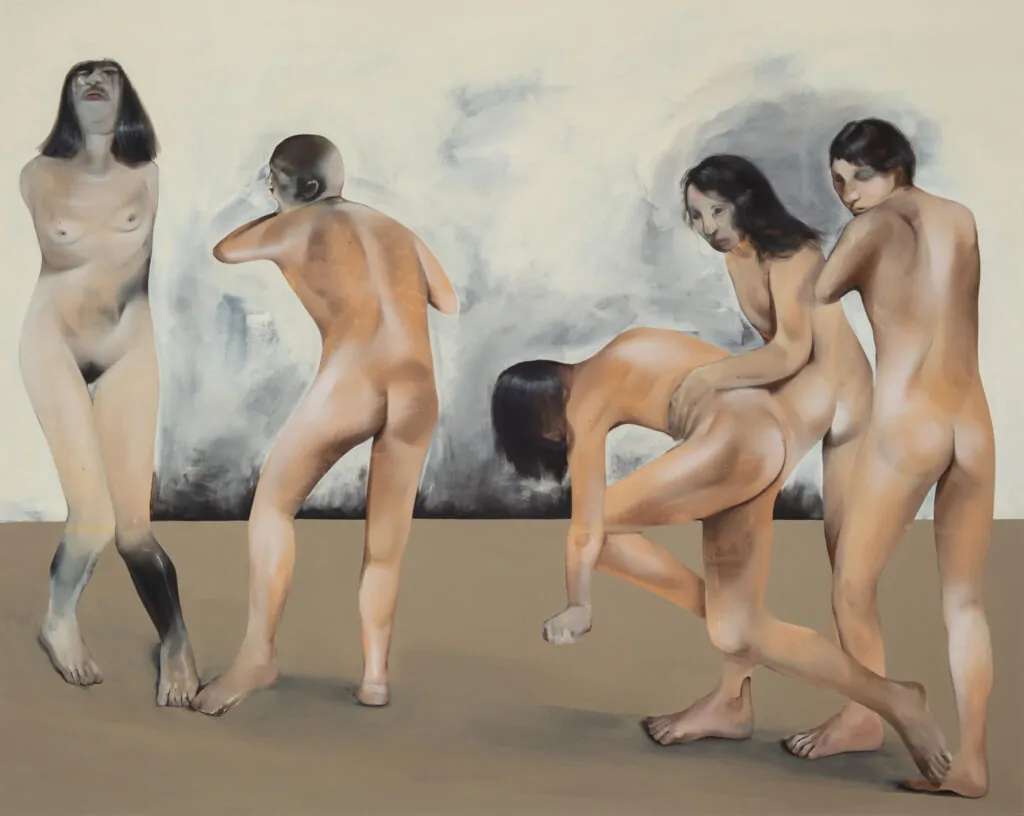

For the British artist Elsa Rouy, skin is not merely a biological boundary — it’s a threshold. A fragile border where the self begins, and, just as often, where it begins to unravel. In her visceral, often unsettling paintings, Rouy explores the contradictions of living in a body — especially a female one — in a world that alternately glorifies, polices, and misunderstands it.

Credit Brynley Odu Davies

The physicality of the paint makes the feeling of flesh more realistic as a thought while also creating a clear distinction between viewer and painting

Elsa Rouy

Drawing on personal experience, Rouy creates scenes that hover in the charged space between pain and pleasure, where emotion resists clarity and the body becomes both subject and battleground.

Rouy’s practice is a sustained investigation into the anxieties of embodiment. She interrogates the strangeness of being self-aware in a physical form — how desire, shame, vulnerability, and power entwine within the skin we inhabit. “When I look at skin as a means of narrative,” Rouy says, “it’s representative of borders between figures, and the tensions that arise by intruding on the borders of the body.”

In her work, skin holds stories. It carries truths, distortions, judgements — our own, and those imposed by others. The familiar desire to feel “comfortable in one’s own skin” becomes, under Rouy’s brush, not a platitude but a painful, often unreachable longing.

Rouy paints the grotesque with nuance, balancing horror and beauty in equal measure. Some figures appear on the brink of bursting, as if consciousness can no longer be contained. Others exist in quieter disarray — a pregnant woman meets the viewer’s gaze with defiant vulnerability; a nude male figure hangs upside down, anonymous, ornamental.

There is little explicit violence, but some scenes flirt with sadism, evoking the visual language of BDSM. The tension lies in the stillness — a stare held too long, a spine slumped under invisible weight. Rouy’s women are swollen, heavy with symbolism and feeling. Her men are reduced, suspended, curved inward, ghost-like.

The skin of her figures is rendered with textures that suggest trauma and transformation: waxy, blistered, bruised. In places, it seems to melt; elsewhere, it hardens into something synthetic. Her bodies are wrapped, distorted, isolated — even in contact, they remain disconnected.

Rouy’s brushwork is deliberate yet instinctive, shifting between precision and abandon. This interplay reveals the emotional volatility embedded in her paintings. Gender and identity blur; figuration dissolves into abstraction. The result is a disquieting intimacy that feels as much psychological as physical.

If there is closeness in Rouy’s work, it comes laced with uncertainty.

Who holds the power?

Who is hurting whom?

Are we merely observers — or are we complicit?

Her paintings feel like raw transcriptions of the interior made visible — psychological states rendered in flesh and pigment. At just 24, Rouy is already drawing international attention. With exhibitions at London’s Guts Gallery and Steve Turner in Los Angeles, she is quietly redefining the visual language of the body. Her figures don’t scream — they rupture, unsettling you with internal truths, as great art is meant to. I dare you to look.

In her latest exhibition, In I Pictured Skin, at Berlin’s GNYP Gallery, it is the psyche that leaks through the canvas — complicated, erotic, wounded, furious. Through a language of bodies and boundaries, Rouy poses a question more compelling than beauty or pain: What happens when the internal becomes impossible to contain? She offers no answers — only the intimacy of flesh, the vulnerability of being seen, and the quiet, persistent violence of looking back.

Born in 2000, Rouy graduated from Camberwell College of Arts and now lives and works in London. We spoke with the artist about her process, her influences, and the uneasy truths that emerge when skin becomes a surface for storytelling.

Your exhibition I Pictured Skin seems to dissect the body not just as a form but as a

psychological threshold—where the self ends and the other begins. How do you approach skin

as both a literal and metaphorical boundary in your work?

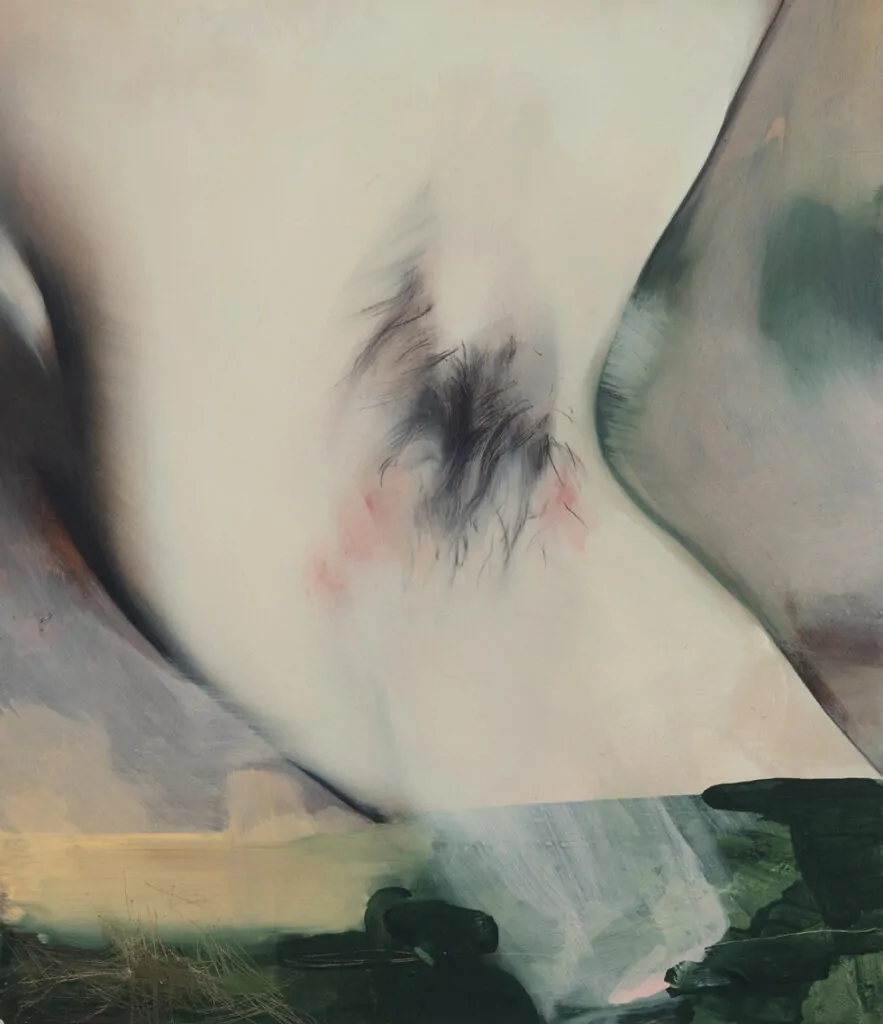

Elsa Rouy: Skin is very present in my work as a way of creating texture and form but also as a representative between the self and the other. If I discuss the way I paint skin, I use layers and brush marks that sometimes bridge or blend with the background or within itself. By doing this, the skin is almost fluid and penetrable and becomes a physical part of the painting. The physicality of the paint makes the feeling of flesh more realistic as a thought while also creating a clear distinction between viewer and painting. However, when I look at skin as a means of narrative, it’s representative of borders between figures and the tensions that arise by intruding on the borders of the body.

Image courtesy of GNYP Gallery

Your work is often described as exploring the tensions between dominance and submission,

revelation and concealment. What role does ambiguity play in your storytelling?

Elsa Rouy: I think ambiguity is important to create meaning in the artworks. I rarely have a set idea of what I want the painting to mean or say. I have a feeling that I want it to embody, but it doesn’t always go the way I want it to. By having the artwork somewhat ambiguous, even to myself, it gives space for the figure and the image to be contemplated and to come alive as its own entity.

The figures in your paintings—particularly female bodies—occupy space in ways that can be

both confrontational and fragile. How do you see your work engaging with the physicality and

psychology of the body?

Elsa Rouy: When I think about the body, I think of it as a means to an end to create an image and an emotion. I find the simplicity of body language, size, and aesthetics interesting in the small nuances and slight changes of distortions can create in the overall feel of an image.

Female-appearing bodies are interesting to me for multiple reasons, one because it’s the closest to what I have, so I can understand and connect to the figures easier, and two because they have been depicted so much in so many different ways it feels challenging and refreshing to see how I can appropriate the figure. For me, the perfect female figure is so overused in media that making such emotional pieces and toying with perfection/imperfection with the body feels liberating.

Acrylic and water-based printing ink on canvas

170 x 140 cm

Image courtesy of GNYP Gallery

There’s a visceral quality to your paintings, where bodily fluids merge and skins seep into one

another. What emotions or sensations do you hope to evoke in viewers?

Elsa Rouy: I think of it more along the lines of boundaries and the body intruding. I think the merging and breaking induces a sort of fight or flight where the viewer imagines that sensation. It’s probably uncomfortable most of the time, but I can imagine that there is something exciting when thinking of the body as a limitless or uncontainable sack or container.

Your figures don’t always have fixed boundaries—they leak, they merge, they rupture. Do you

see your work as an act of erasing boundaries, or of exposing the ones we pretend don’t exist?

Elsa Rouy: I wouldn’t say it’s exactly an erasure of boundaries; I think my work is based on boundaries. The emotions that exist in the pieces wouldn’t be possible without the boundaries. I think of it more as a complete perversion and disregard of the boundary that is there, and then trying to find a way to reform the boundary around the perversion.

You’ve spoken about addressing shame, guilt, and the complexities of female sexuality in your

work. How has your own relationship with these themes evolved through painting?

Elsa Rouy: I’m not too sure — I think my artworks are sometimes more comfortable with these themes than I am myself. I aspire to be as bold.

Acrylic on canvas

70 x 60 cm

Image courtesy of GNYP Gallery

The human form in your work is often stretched, distorted, or fragmented. What draws you to

pushing the body beyond its natural confines?

Elsa Rouy: The body doesn’t often feel like it fits its natural confines, so I try to paint it more accurately to the feeling.

Your figures exist in an unsettling space between suffering and pleasure. How do you navigate

the fine line between the grotesque and the beautiful?

Elsa Rouy: I think there’s a fine line between suffering and pleasure. I was talking to Emily Steer about masochism and sadism while discussing the press release, and how we all contain both sadistic and masochistic tendencies. The conversation made me think about pleasure and pain — how the two fit together. Do we enjoy being in pain, in being sad? Can we find pleasure uncomfortable and difficult to process? I came to the conclusion that having both, and being unsure where we exist between the confines of pleasure and pain, is just living.

Acrylic on canvas

140 x 100 cm

Image courtesy of GNYP Gallery

Do you view painting as a way of reclaiming bodily autonomy—especially in an era where the

female body is still heavily scrutinised and regulated?

Elsa Rouy: Definitely — my figures are my figures. I paint them, I manipulate them, and I can make them be or do whatever I want. I don’t think having a body actually gives us that much freedom to express our existence — either without it being natural, or without it being judged, or without physical impossibilities. I struggle with the idea of the body because its image, performance, and meaning are all societally based, and I think this can create issues with connecting to ourselves.

200 x 250 cm

Image courtesy of GNYP Gallery

Your paintings disrupt conventional depictions of the body. Do you think there is still an

expectation—spoken or unspoken—that artists (especially women) should depict the female

form in a certain way?

Elsa Rouy: I’m not too sure about that answer. Probably — if I think about artwork I see in shows. But I’m not sure, because I do see a lot that definitely challenges and feels like a fresh perspective.

What do you think is the biggest misconception about your work, and what do you wish more

people understood?

Elsa Rouy: That it’s just about sex. Hardly any of my newer pieces — for years now — have been about sex. It was never just about the erotic; it’s always been about the emotions, even when it was erotic. The body isn’t important. The body, as I said earlier, is a means to an end — to create a feeling, an emotion, to make the composition work.

The bodies are not much different from the paint and how it’s applied; together they form a discourse. The nakedness of the figures is important to create a conversation around layers, boundaries, and physicality — to create awkwardness and tenderness. The bodies are objects, but they’re not always sexual. They’re a point of recognition and understanding.

Acrylic on canvas, 70×60 cm

What themes are haunting you right now—what questions remain unanswered in your practice?

Elsa Rouy: Where do I want to go from here? What does my work mean to me? Am I still enjoying what I make?

You studied at Camberwell College of Arts and have had solo shows in London and Los

Angeles. How have these experiences shaped your approach to painting?

Elsa Rouy: Attending Camberwell gave me the opportunity to move out of my hometown and to live and make work in a more cultural environment. It gave me the chance to have a studio and to develop my practice on my own terms. Having solo shows has taught me a lot about discipline, time management, and creating cohesive bodies of work. It’s made me think of my practice as a whole, rather than just painting to painting.

Finally, how would you articulate your philosophy of art—not just as a practice, but as a way of

living, perceiving, and being in the world?

Elsa Rouy: I guess it’s an act of observing and creating — reshaping things and ideas in the hope of progression.

Elsa Rouy: I Pictured Skin opens on the 14th of March, 2025 until the 26th of April, 2025 at GNYP Gallery

©2025 Elsa Rouy