Through poetry, protest and power, Helen Cammock explores two centuries of law, reminding us that justice is never static.

Turner Prize–winning artist Helen Cammock has long used her practice to ask difficult questions of history, voice and power. Awarded the prize in 2019 alongside her fellow nominees, she embraced the spirit of collaboration over competition, a gesture that speaks to the politics of Cammock’s work as much as its form.

Now, commissioned by the Law Society to mark its bicentenary, she turns her gaze towards two centuries of legal legacy, creating a suite of works that both reflect on the fragility of justice and insist on its potential.

Cammock sees the law as a paradox — founded on ideals of fairness, yet often shaped to protect privilege. She reminds us that while society has transformed since the 1820s, one principle has endured: those with wealth and influence often encounter the law differently from those without. Her work for the commission acknowledges this imbalance but also extends a call to imagine a legal system that truly protects and guides all in its name.

The law is founded in certain principles that clearly do not protect or serve everyone equally: principles that were designed to protect a certain gender, certain races, certain classes

Helen Cammock

Through poetry, banners, drawings and text, she layers symbolism and material histories. A fabric banner, A Balanced Scale, speaks both to protest traditions and to the demand for workers’ and human rights. Across it runs the phrase No one above the Law No one Beneath Protection, a reimagining of Roosevelt’s words that she uses to underline the dual principles of accountability and equality. Hung at the Law Society’s library entrance, it becomes a threshold between the weight of legal history and the promise of justice.

Cammock’s poem An Ode to the Just urges today’s lawyers to reckon with their inheritance — to question and challenge as much as they uphold. Her suite of drawings, A People’s Practice, acknowledges the demands placed on legal professionals: the fatigue, contradictions and multiple pressures of their work. For Cammock, the choice of materials — cotton, wool, steel, wood — is no accident. They are strong, unpretentious, bound to histories of labour, colonialism and industrial struggle.

This commission follows a trajectory of works that link overlooked histories to contemporary struggles. For The Line, London’s public art walk, she embedded poetry and song into the landscape, tracing how voices of protest and resilience resonate across a city. In The Long Note (2018), she drew connections between Irish women’s civil rights and Black liberation movements, demonstrating her commitment to uncovering the entanglements of survival, resistance and freedom.

She recognises that justice is never static. “The law can be bent, manipulated and abused,” she explains, but she also honours those who fight daily to uphold its best principles — solicitors working to defend civil liberties, to protect the vulnerable, to ensure care in the most difficult moments of people’s lives. What she celebrates is not a flawless system, but the human commitment to fairness even within flawed structures.

Lament, a recurring theme in her work, runs beneath this commission too. For Cammock, lamentation is not only sorrow but a reckoning, a way of touching pain in order to generate empathy. Without empathy, she argues, justice cannot survive. Her works ask us to sit with that discomfort and let it move us towards change.

The Law Society’s decision to commission her — a Black British artist known for interrogating power, history and resistance — signals a willingness to be questioned as much as celebrated. Cammock does not take the invitation lightly: she sees it as a statement of commitment to the rule of law at a time when justice itself feels precarious, both domestically and internationally.

Her philosophy of art is inseparable from how she lives: to notice and to question, to listen as much as to speak, to challenge structures that limit the voices of some while amplifying others. For her, art must stir, provoke, soothe and inspire. It must open possibilities for empathy and change, however small.

In this bicentenary commission, Cammock does more than mark a milestone. She asks us to see justice as fragile, to reckon with inequity past and present, and to imagine a future where the law serves all — not just the lucky, the privileged and the powerful.

This commission marks the Law Society’s bicentenary, a moment weighted with history. How did you approach weaving together two centuries of legal legacy with your own language of poetry, voice and visual symbolism?

Helen Cammock: Two hundred years is a substantial period and invites us to consider all of the many changes that British society has experienced. We imagine that contemporary society is very different from two centuries ago – and yes, this is clearly the case – but the underlying principle, that the powerful and wealthy experience a completely different relationship with the law and legal systems compared to other members of society, persists.

The law is founded in certain principles that clearly do not protect or serve everyone equally: principles that were designed to protect a certain gender, certain races, certain classes and so on. I wanted the work I make to reflect this problematic but also to celebrate and encourage a potential for change. I am suggesting a commitment to a legal system that interprets the rule of law as a guidance and protection for all in its name.

The work I have made to mark this moment uses poetry, visual symbolism and different materials that represent a democratisation and respect for labour. The fabric banner A Balanced Scale speaks clearly to the protest banner but also the notion of workers’ rights and activism for human rights. It contains the text No one above the Law No one Beneath Protection.

It is a nod to the phrase coined by Theodore Roosevelt and we understand it to express the dual principles of the rule of law and human rights, asserting that everyone (including government) is subject to the law, whilst also emphasising that all individuals are entitled to equal protection under that law. This ideal is intended to ensure a just society where power is not exercised arbitrarily, all people are treated equally and have their basic rights respected. The work will be hung outside the Law Society’s library entrance – a kind of statement of commitment as you enter a library full of legal tomes and histories of the profession.

An Ode to the Just is a new text work that I’ve written based on rhyming poetry; it calls to attention the historical legacies that the contemporary professional has a responsibility to consider, question, challenge and uphold in equal measure. There has been a real change in the demographic of those entering the profession and this will also inevitably bring some movement when those who interpret and uphold the law have different positions in society and different experiences of society.

The work A People’s Practice uses symbolism in line drawings to attempt to acknowledge the different tensions, emotions, pace, exhaustion and multiple intersects that the practice of law demands of its professionals.

All the materials used across the works are intentionally materials that are part of labour processes. They are strong materials – cotton, wool, steel, wood – and they lack pretension, yet all hold different layered histories: workers’ rights, colonial legacies and the industrial processes and struggles in the UK.

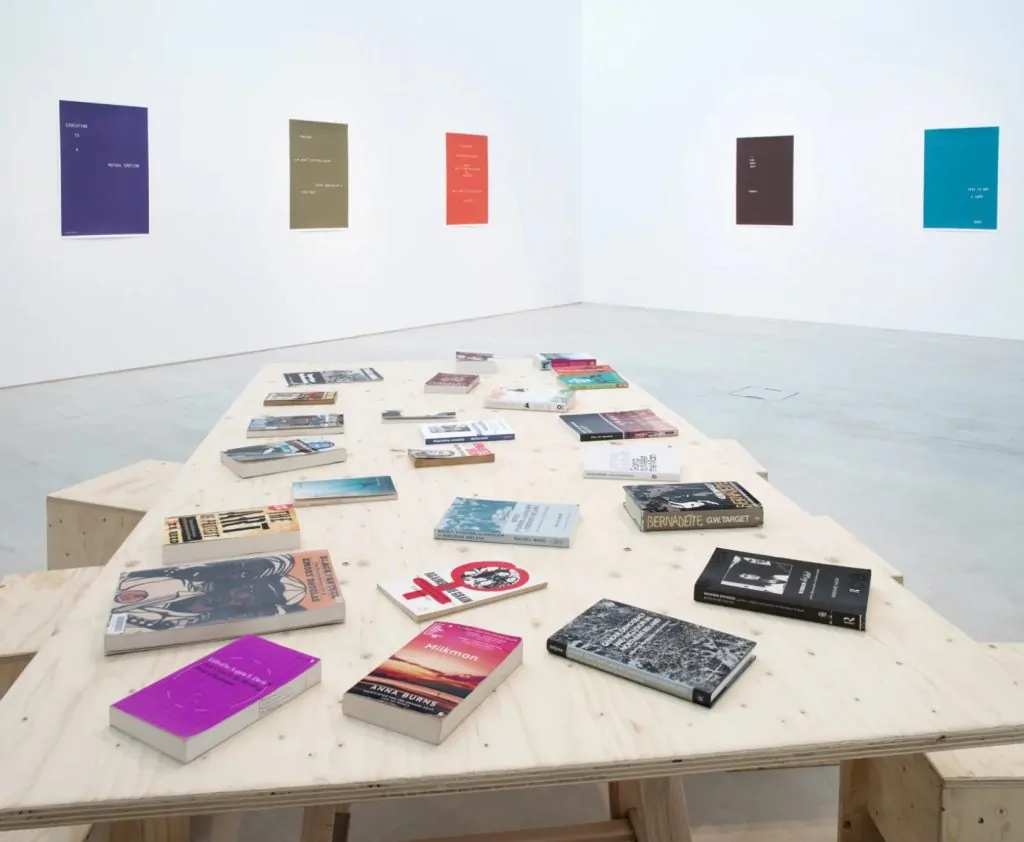

Turner Prize, 2019

Installation view, Turner Contemporary, Margate

Photography by Stephen White

You’ve said that “law is vulnerable to manipulation, bias and abuse.” How do you hold that tension – between celebrating the values of justice and exposing the fragility of the law – in this new work?

Helen Cammock: I think firstly there is something in the actual speaking of this tension that allows the space for celebration. The abuse of law, the creation of legal systems, are all based on power structures – who gets to decide, who gets to preside, who gets to change and contest laws. Justice is not a constant and stable concept – it moves and slides around depending on who we are. We don’t all have access to the same systems of justice and care before the law.

The examples to support this are, of course, never-ending – this is a live dialogue across different contexts, geographies, and historical moments – so what I’m celebrating are some of the principles that are about justice and fairness, and the commitment to the aspiration to this.

I celebrate here the lawyer/solicitor who is working to represent people’s civil liberties and rights: attempting to ensure that people are cared for as they age, when they enter a new country frightened and alone, supporting people who are ending a relationship, and so on.

We are living in a particular moment where laws are being changed and manipulated by avaricious heads of state and citizens wielding power for their own satisfaction… of course, I speak of Trump, Putin, Netanyahu, but also people with wealth who manage to ensure the laws bend and sway for them in many situations.

The very premise of the idea of the law I am suspicious of, because I know that its roots are to benefit the well-being of those who owned land, bodies, and systems intended to replicate their power. But I do believe that people have fought long and hard to change laws – women’s right to vote, LGBTQI+ rights, reproductive justice, civil rights including laws to tackle racial discrimination.

But I am also very aware that trans rights across the world are being continually attacked through legislature; LGBTQI+ rights globally; universal access to books and learning in the US; indigenous rights; and of course, human rights to a safe existence on an international scale.

I believe that law is vital because there are many individuals, communities, and nation states who want the law to serve only their protection and their rights – and it is the role of those working in the legal system to commit to the protection of all under the law, and to challenge any changes in law that undermine these principles.

The commission is intended to be a lasting art piece bridging past, present and future. What do you hope future generations of lawyers – or indeed ordinary citizens – will read in this work 50 or 100 years from now?

Helen Cammock: I suppose the importance of conversations around ethical practice, the value of mutual respect, and a commitment to striving for an equity before the law for all. This is, at least, a hope that is held in the work.

I hope that the Ode to the Just stresses, but also celebrates, the importance and weight of responsibility that sits with lawyers. I see the suite of works as a kind of call to action – asking for a commitment to strive for justice and protection for all – whilst acknowledging just how much this asks.

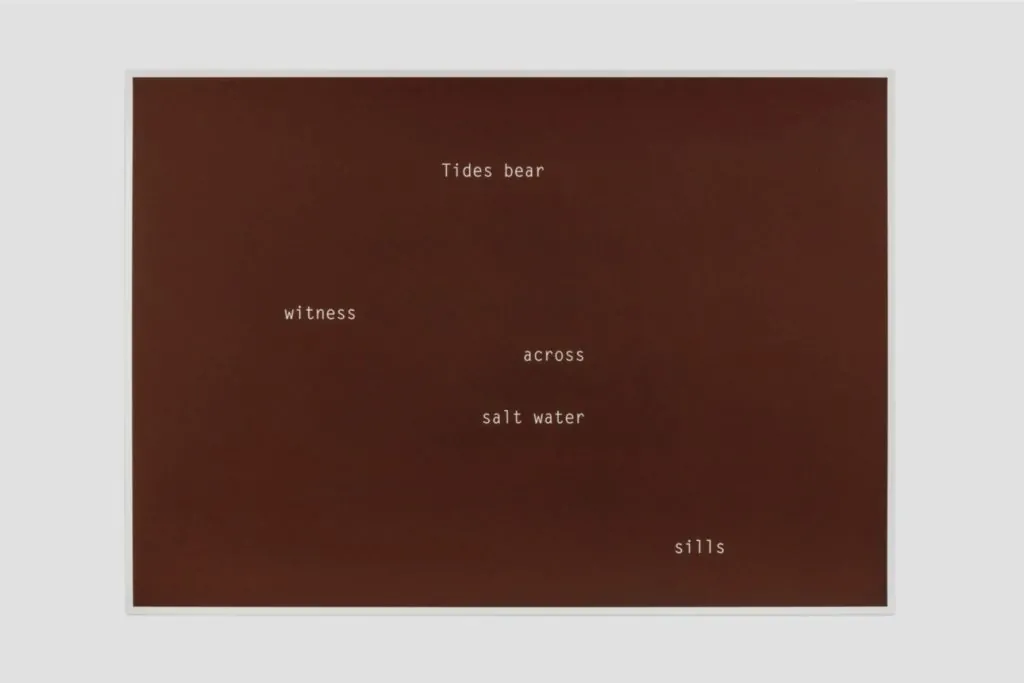

Tides, 2022

screenprint on paper

72 x 102 cm

Edition of 5

Poetic language is central to your practice. How does poetry interact with the authority and rigidity of the law in this project?

Helen Cammock: Poetry gives space – to reflect, to feel, to interpret. It has an openness and relies on an economy of words. I don’t have a background in law, but this feels almost oppositional to the way I understand law as a discipline operates.

There is something about having to think outside of the words themselves – a kind of wandering through different planes that the poetic offers – and this is where we do our own thinking, feeling, and being.

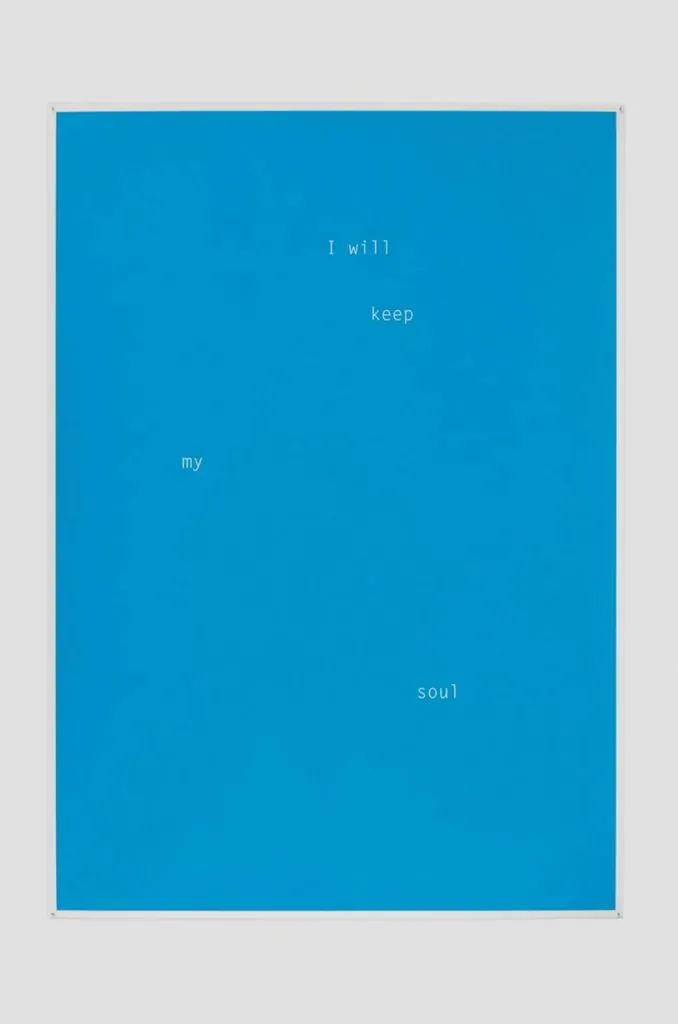

I Will Keep My Soul, 2022

screenprint on paper

72 x 102 cm

Edition of 5

Your work often layers overlooked or silenced voices across time. Did you uncover particular histories of law, legal struggle or community voices that helped shape this commission?

Helen Cammock: In this commission, I decided to focus on the structures of law and to speak directly to those who work within these structures – lawyers and legal practitioners. I suppose by making this decision, the silenced voices are implicit rather than explicit in the work – absolutely present in what is being asked of the profession.

The works are an offering that utilises symbolism. These works will, I hope, last for some time, and so they are asked to speak for and about many different individuals and communities affected by the processes of law.

So I chose not to be specific, but people and communities are absolutely there in the work, and I would hope in our consciousness when experiencing the work.

Photo Ros Kavanagh

In The Long Note, you connected Irish women’s civil rights struggles to wider Black liberation movements. Do you see the Law Society commission as part of that same continuum of uncovering and linking struggles?

Helen Cammock: All of my work is about intersectionality and the entanglements of subjugation, struggle, liberation, and freedom that bind us together. I am constantly asking of the viewer to consider who they are in any given moment. We are always in and part of every situation, even if we believe we are not. Our lives and opinions, our struggles, cannot be disentangled from others.

The unravelling of the tangles can only begin when we realise we are part of each other’s survival, existence, and demise and destruction.

You’ve spoken of lament as both personal and political. Can lament find a place within a work that celebrates a legal institution, or does it exist more as an undercurrent in this commission?

Helen Cammock: I think the very provocation to consider equity before the law and ideas of justice stimulates a reflection on structural inequity and injustice. Once we begin to consider inequity and injustice, then lamentation cannot be avoided. Lamentation, for me, is about sadness, yes – but it’s also about a knowing, a reckoning, and therefore strength, wisdom and a longing for something different – for change. To lament is to be in touch with pain, and I believe this is the only way to effect change.

It cannot happen when people are switched off, numbed, not in touch with their own pain – because without this, there is limited capacity for empathy. We need empathy to fight for what is right for all – not just for ourselves or for people who look or sound like us.

Lamentation is a foundational experience for empathy – just as love and care are.

At this moment, when the “international rule of law is being ignored on many fronts”, what role do you think art can play in reminding us of justice’s fragility?

Helen Cammock: For me, art needs to reflect the life that is lived – it has the potential to do so many things: to question, to challenge, to expose, to transform ideas, to resist, to translate, to stimulate emotional response, to soothe, to echo, to bring hope when we may imagine hope is gone… it is a tool for loving and a tool for fighting, and it takes so many forms.

The art that interests me is the art that has the potential to do something – an activation. International rule of law is continuously ignored – sometimes with catastrophic consequences for populations en masse, such as the genocide of the Palestinian people or the inequitable incarceration of Black men in prisons across the western world.

What is clearly exposed is that some have a greater right to life than others, and that we certainly do not yet have equity before the law internationally or domestically.

On WindTides, 2024

Stencil cut powder-coated steel letters

The Line, London Couresy of Kate Macgarry

The Law Society chose you – a Black British woman whose work interrogates power and resistance – to create this landmark piece. How do you read the significance of that

invitation?

Helen Cammock: I think it’s a commitment from The Law Society to the principle of the Rule of Law and to the upholding of justice, in a moment where, domestically and internationally, this is under attack. It’s a willingness to knowingly invite an artist who will reflect upon the flaws in the ways the law is sometimes interpreted, manipulated, abused, and who also strives to talk about justice/injustice, equity/inequity in whatever she produces.

Looking forward, what questions remain most urgent for you as an artist – questions you want to keep pressing in your work after this commission?

Helen Cammock: Freedom, equity, justice, breaking down and revealing systems of power wherever I come across them. I’m interested in doing this through dialogue and enquiry – no one has all the answers, and only together do we have a chance of finding some of the answers to the damage that is persistently done to some individuals and communities for the benefit of others. I want to talk about the damage and the shape it takes – so sadness also has a place in my work… but also the ways we find joy, love, resistance and resolution.

Finally, what is your guiding philosophy of art – what do you believe art should do in the

world, and how does that conviction shape both your practice and the way you move

through life beyond the studio?

Helen Cammock: The art I make is an extension of myself… of the way I want to and hope to live my life. I want to notice and question as much as I can. I want to think and feel as much as I can. I want to hear what others have to say, as well as having the space to speak for myself; and I want to challenge the structures that restrict this opportunity for some and not others.

I want to make art that stirs, challenges, provokes, but also soothes and excites. I want to make art that may be a part of effecting small changes in the way people see themselves and others.

I want my work to connect with others, and I hope that people may be touched and moved by it.

I suppose I hope this is how I walk in the world – that my presence, and what I do with it, may in some way support changes (however small) in myself and in others.

©2025 Helen Cammock