Shanghai-born artist Ding Yi returns to London with new works that transform his signature crosses, moving from the geometry of China’s urban skylines to the cosmologies and landscapes of Tibet and Yunnan.

When The Road to Heaven opens at Lisson Gallery, it marks Ding Yi’s first London solo exhibition in over five years. Best known for his long-running Appearance of Crosses series, the Shanghai-born artist has spent this interval turning outward, from China’s urban sprawl to landscapes, cosmologies and spiritual systems rooted in Tibet and Yunnan.

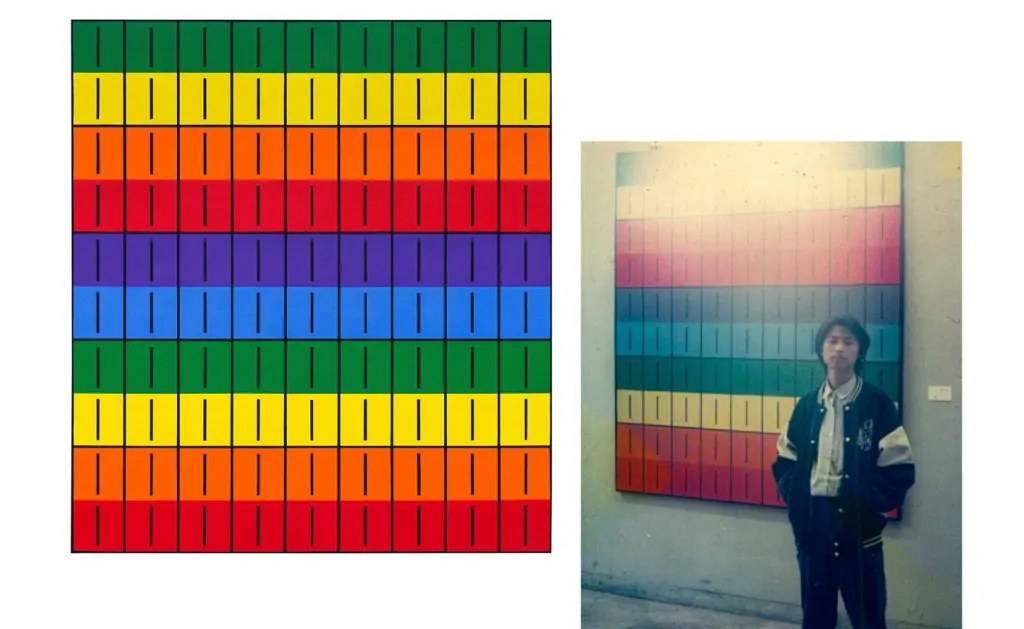

Born in 1962, Yi came of age during the Cultural Revolution, when classrooms doubled as political stages. His earliest lessons in art were propaganda sketches, less brushwork than ideology. That imprint carried into formal training and was eventually reshaped into the radical abstractions that would define his career.

The creation of the Tibet series was a new opportunity for me, offering the possibility to observe local history, culture, and vast landscapes

Ding Yi

In recent years, he has shifted from observing Shanghai’s skyline to engaging with Himalayan terrains and Naxi cosmology. Where his crosses once mapped the geometry of urban modernity, they now reach into animist traditions, mythic calendars and sacred mountain ranges.

The turn began during journeys through Tibet in 2021–22. At Everest Base Camp, 5,300 metres up, he felt abstraction merge with a sense of spiritual ascent. Soon after, repeated visits to Yunnan brought him deep into the Naxi people’s Dongba culture, with its pictographic scripts, funerary scrolls and the epic cycle The Road to Heaven. Yi was struck by their belief in life’s return to the ancestral land, a vision that resonated with his own attempt to create order in chaos through the cross.

The Dongba narrative, in which the soul travels from earthly struggle to transcendence, mirrors his own pursuit of abstraction. His grid of crosses, first conceived as cool, rational coordinates in 1988, has become a pathway to spiritual experience. That transformation demanded new materials. Dongba paper, handmade in Yunnan from bark and wolfberry grass, resists precision. Pigment bleeds into its fibres, giving his marks a raw, breathing density. For Yi, each material carries its own cosmology, extending his early fascination with papers and pigments across Asia.

The works feel rooted yet universal. Basswood reliefs, scarred with rhythmic grooves, echo mountain topography. Star maps of the Twenty-Eight Mansions expand his earlier constellation series, refracted now through Naxi cosmology. As Yi reflects, different cultures have long observed the same skies from entirely different perspectives, and he seeks to return these stars to the heavens.

If the cross once served as a rejection of emotion and ideology, it now carries the weight of nearly four decades of inquiry. What began as formalist detachment has evolved into meditation and homage. He frames his career in stages: steadying (formal abstraction), overlooking (urban modernity) and looking up (cosmology). Next may come looking inward. For now, his practice rests on what he calls “the miracle of encounter”: learning from other cultures without exoticising them, bringing their knowledge into dialogue with his own.

“I don’t want to become a fundamentalist abstract painter,” Yi admits. “Each exhibition is a risk. But I still believe in discovery, in anticipation of the miraculous.” For London audiences, The Road to Heaven is less a fixed cosmology than an experiment, an artist testing the limits of abstraction through cross-cultural encounter.

Ding Yi: The Road to Heaven opens on the 26th of September, 2025 until the 1st of November, 2025 at Lisson Gallery

Your exhibition The Road to Heaven at Lisson Gallery marks your first solo show in London in over five years. Why was now the right moment to return, and what do you hope London audiences will see diBerently in your work this time?

Ding Yi: In recent years, the focus of my work has shifted from the observation of urban landscapes to the exploration of old spiritual cosmologies. Recent travels centered around the Himalayas and encounters with the Dongba culture of the Naxi people have infused “Appearance of Crosses” with new energy and dimensions. With the opening of “The Road to Heaven” at Lisson Gallery, I believe now is a good time to present these phased outcomes to the London audiences.

My previous works might have been closely related to the urban fabric of Shanghai, while some works presented in “The Road to Heaven” originate from the mountainscapes of the Hengduan Mountains and the Naxi people’s spiritual contemplations.

I have extensively used Dongba paper, a local handmade paper from Yunnan. The audience should be able to perceive an intense, almost ritualistic materiality and spiritual density.

This body of work grows directly out of your research trips to Yunnan and your engagement with

Dongba priests and scholars. What first drew you to the cosmology of the Naxi people, and how has that encounter reshaped your practice?

Ding Yi: If I were to trace the catalyst, it would be my trip to Tibet in 2021-22 and my solo exhibition held in Lhasa in 2022, which presented a series of new works influenced by Tibet. The creation of the Tibet series was a new opportunity for me, offering the possibility to observe local history, culture, and vast landscapes. I reached the Everest Base Camp at 5300 meters, fulfilling a dream I had since my student days in the 1980s.

Simultaneously, it was a spiritual turning point. The creation of the Tibet series allowed me to understand the local’s spiritual beliefs and sense the sacredness latent in the landscape. Starting from this, my recent creations and exhibitions, from Lhasa, Qingdao, Ningbo, Shenzhen to Kunming, have revolved around site-specific travels, expanding the dimension of “spirituality” through in-depth investigations of regional cultures.

Last year, I traveled three times to the ancient Naxi region in Yunnan. I was deeply attracted by the animism, nature worship, the view of life returning to the ancestral land, the mysterious calendar of the Twenty-Eight Mansions, and the epic depiction of the soul’s journey in The Road to Heaven. I decided to focus on Naxi and Dongba culture for this exhibition.

Dongba script is a pictographic script still in use today. Furthermore, classics like The Road to Heaven in Dongba culture construct a complete illustrative system about the soul’s journey and reincarnation system. This resonated with my long-term work of constructing order and seeking transcendence through the “Appearance of Crosses”. It represents an inspiration for “abstraction” from a completely different cultural tradition, one not filtered through the path of Western modernism.

Courtesy of Lisson Gallery

The exhibition title comes from the Dongba funerary scroll The Road to Heaven. How did the spiritual narrative of the soul’s journey resonate with your ongoing artistic inquiry into abstraction, order and transcendence?

Ding Yi: The Road to Heaven depicts the soul’s journey overcoming hardships to return to the ancestral land after death. This is essentially a narrative moving from chaos to order, from the earthly to the transcendent. This is similar to the propositions explored by “Appearance of Crosses” over the years: how to establish a coordinate through the rational order of art within an infinite, chaotic world, and through this coordinate, attempt to touch something eternal or transcendent.

The Road to Heaven unfolds a spiritual path for me. Each Dongba priest, while hand-painting The Road to Heaven, undertakes the mission of guiding others’ souls while also embarking on their own spiritual ascent. The Road to Heaven constructed through the accumulation of crosses resembles more a soul’s ascent in an abstract dimension. Order here is no longer the endpoint but the path leading to spiritual experience.

You’ve described the works on Dongba paper as a “translation” of cosmology into your cross motif. How do you balance homage with transformation when working with such a culturally specific source material?

Ding Yi: “Homage” refers to a humble “looking up” in the face of culture, while “transformation” is essentially the artist’s inherent task. While preparing for this exhibition and the “The Winding Path” at the Contemporary Gallery Kunming and the Anthropology Museum of Yunnan University, I spent considerable time learning and feeling rather than simply appropriating imagery, so as to avoid the so-called anthropological or sociological lens of “colonial exoticism” or “Western-centrism.”

I did not deliberately imitate specific Dongba script or the motifs of “The Road to Heaven,” but sought to understand the underlying worldview – for example, how the Dongba people perceive the relationships between heaven, earth, humanity, and the divine. The unique texture of Dongba paper makes the crosses appear more rustic and powerful on this paper.

If the core of the “The Road to Heaven” exhibition is the awe towards the cosmos and spirit inspired by Dongba culture, the formal language of expression must remain purely personal. Taking the “Twenty-Eight Mansions” as an example, starry skies and constellations have been one of the key motifs through my recent work since the Tibet series.

The diagrams of the Twenty-Eight Mansions used for calendrical calculations and divination in Dongba culture introduced new developments to this theme. The graphical representations of the twenty-eight mansions in Han Chinese culture and Naxi culture are different; on the same land, different ethnic groups observed these celestial bodies from completely different angles at different historical stages.

I want to return these star charts to the sky, to observe these patterns anew. While paying homage to the original culture, if viewed in connection with my previous constellation series, these works actually present a flow of time and space.

500 x 1185 cm 196 7/8 x 466 1/2 in

The cross, both “+” and “x,” has been the heartbeat of your practice since 1988. After decades of repetition, what continues to surprise or challenge you about this deceptively simple form?

Ding Yi: “Appearance of Crosses” has a simple form and basic structure, yet possesses infinite capacity. It can carry my life experiences, observations, and thoughts from different periods. Initially, it carried the rationality opposing traditional Chinese art; later, it reflected the landscapes of urbanization; now, it can connect with ancient cosmologies and eternal spirituality.

Your cross began as a way to strip painting of emotion and ideology, yet in recent years you’ve spoken of moving towards intuition and feeling. How do you reconcile the rational origins of the cross with its growing spiritual dimension?

Ding Yi: In 1988, I attempted to use a purely formalist language to sever all possible connections with reality. After nearly 40 years of creating the “Appearance of Crosses” series, I needed to find new sources for my work.

It couldn’t be created out of nothing, nor could it be the early formalism; it had to be alive, synthesizing the history and culture of different regions and ethnicities. Only by fully immersing myself and rediscovering and observing this world can a true source of “spirituality” emerge.

You’ve described your practice in three stages: ‘steadying,’ ‘overlooking,’ and now ‘looking up’. Could you expand on how this current stage differs from the earlier ones, and how it changes your understanding of abstraction?

Ding Yi: Over the past forty years, the evolution of the “Appearance of Crosses” can roughly be divided into three phrases. ‘Steadying’ was the period of pure abstract idealism, where formalist research and exploring the origin of abstraction were the main direction.

The ‘Overlooking’ period discussed the sensory magical landscape of Shanghai’s urban transformation and China’s urbanization process from a neutral standpoint. ‘Looking up’ involves cosmological thinking, looking at the sky, the stars, and a larger world, shifting from a bipolar view of China and the West to a worldview encompassing more civilizations and regions. It focuses on the intersection of new phenomena of the era, the eternality found in ancient civilizations, and the primitiveness presented by nature, attempting to personally reconstruct cartology, the steles, and virtual worlds akin to online games.

The current stage might be the beginning of ‘Looking-Inward,’ but I’m not entirely sure yet, as ‘Looking-Inward’ is essentially another term for spirituality. The current ‘Looking-Up’ first signifies a change in stance. For ethnic minorities, the perspective adopted by external creators when representing their culture is crucial. Rather than using a top-down perspective to help or change them, appreciating their culture, recognizing it anew, and learning from it is the starting point of ‘looking up.’

During the actual process of understanding, I also discovered many things worth learning from. For example, the traditional natural view in Dongba culture advocates protecting nature and taking from it limitedly, which is actually a quite novel concept. Additionally, I interviewed the director of the Mosuo Museum, who discussed cases related to the “walking marriage” custom. In remote villages, this is a highly adaptable and quite advanced social system, playing important roles in property inheritance, wealth distribution, and population growth.

Many of the works in London are executed on coarse Dongba paper, whose texture resists perfect precision. How has this material altered the rhythm and density of your mark-making compared with canvas or wood relief?

Ding Yi: When I painted the first version of The Road to Heaven, I discovered Dongba paper in a shop in Lijiang. It’s made from beaten bark pulp, has long fibers, and doesn’t get soggy easily. Moreover, it contains wolfberry grass, which prevents insect damage. Dongba scriptures are usually written on this paper, which can be preserved for a long time. It also allows for a slight bleeding of the pigment. I utilized this characteristic in the “Twenty-Eight Lunar Mansions” series, using acrylic diluted with water to create a “bleeding” effect.

I have always been very interested in materials. Image and material are important ways to break through tradition. Early on, I conducted many material experiments, using various papers, pigments, and tools, including trying Anhui Xuan paper, Japanese paper, Indian paper in recent years… the most used is Canson.

I like handmade paper; it can bring me many new possibilities and inspirations, which in turn indirectly change my painting language. At the same time, I believe that to understand a local culture, it’s best to find some relevant materials. The materials commonly used by an ethnic group can bring your creation into a scenario of dialogue with them.

Courtesy of Lisson Gallery

In your relief paintings carved into basswood, there is a strong sense of mountains, geology and landscape entering your abstraction. Do you think of these works as extending the cross motif into architecture or topography?

Ding Yi: Yes, that’s a very accurate observation. The composition of these basswood panels originates from the Hengduan Mountains. They are located in western Sichuan, Yunnan, and eastern Tibet. Geographically, the Hengduan Mountains overlap with my two recent trips, one to Tibet and one to the ancient Naxi region.

I did intentionally extend the “Appearance of Crosses” into the field of topography. There is a “Himalayan culture” territory in my recent creations. The ancient Naxi region in Yunnan has a natural connection to Himalayan culture: one is the geographical connection formed by the Hengduan Mountains, and another is the cultural connection: the Dongba culture actually originates from Bon.

The Naxi are a migratory people, basically migrating from the northwest or the Ali Plateau. This thread runs through my previous connection with Tibet, becoming an extension. For this show in London and the ongoing “The Winding Path” in Kunming, I hope to incorporate more of Yunnan’s local culture. If possible, my next step is to expand the exploration of topography to South America.

Your grids and systems are often linked with Western abstraction, yet your work is also rooted in Chinese contexts. Do you feel closer to a global lineage of abstraction, or to a specifically Chinese visual tradition?

Ding Yi: Initially, my abstract system originated from Western modernism. This foundation in abstraction has developed over nearly 40 years, incorporating elements facing traditional Chinese culture, as well as elements facing China’s urbanization process. Today, we understand that Western abstraction has also undergone grafting and development in different regions and from different cultures during globalization. The lineage of a century of abstraction requires perspectives to explore new possibilities. This might be a personalized, unique perspective, a hybrid perspective. Therefore, I will not define myself, or rather, limit myself to belonging to a specific lineage or tradition.

Courtesy of Lisson Gallery

Your early works mirrored Shanghai’s frenetic modernisation, while your recent work seems to search for older cosmologies. Do you see this shift as personal, generational, or perhaps a response to broader changes in Chinese society?

Ding Yi: An artist’s growth is based on the continuous expansion of thinking and horizons. After an artist experiences intense reactions to the present, they inevitably turn to more fundamental, more eternal questions. When young, with limited experience, the world seen is partial. As age and knowledge grow, the world one can see approaches a fuller picture. Therefore, one doesn’t confine oneself to the micro-changes of a single city or place but tries to take a broad overview, seeing how the entire world is constituted, and attempting to express this constitution through works. So, this is a process of growth and change. I stopped using fluorescent colors ten years ago, actually realizing the so-called “thousand cities with one face” in Chinese and many similar drawbacks in urbanization, thus trying to broaden my perspective.

In Tibet and now Yunnan, you’ve engaged deeply with specific cultural geographies. Do you see these projects as a way of anchoring abstraction in lived history, resisting the idea of it as purely universal or placeless?

Ding Yi: The artistic explorations in recent years have made me realize that universality must be reached through specific, profound re-understanding of different civilizations and hands-on, site-specific exploration. The projects in Tibet and Yunnan are precisely meant to provide a solid “anchor” for my abstraction. I am like someone working on a jigsaw puzzle; the Tibet and Yunnan pieces are parts of the puzzle. In the future, this puzzle might include more and more pieces, eventually forming a large system.

The same applies to the perception of the “universal” in abstraction. One must open the door for more and newer things to pour in. I do not wish to become a “fundamentalist” abstract artist. Creators of abstract art can easily become formalists, clinging stubbornly to old sets. At a certain stage, so-called stylistic recognizability becomes an artist’s market guarantee, but this guarantee is equally dangerous.

The key lies in how to view it and adjust it: creation cannot lack passion and be mere repetition. I still hope to uphold an exploratory spirit to accommodate larger things, maintaining a vibrant state. For each exhibition, I take risks. Even though the outcome is unknown, I am happy during the process, anticipating miracles every day. This feeling is the state an artist needs.

Courtesy of Lisson Gallery

In engaging with Dongba religion and other cosmologies, do you see your work as a form of spiritual practice, or is it primarily an intellectual exploration?

Ding Yi: I believe that in the best state, the two are united. Intellectual exploration is the entrance, the foundation for understanding. Without serious study and thought, so-called “spiritual practice” can become superficial mysticism.

But when you go deeper, the process of painting itself does indeed become a form of spiritual practice. The process of depicting crosses in the studio is one of high concentration and meditation. It allows me to detach from daily trivialities and enter a quieter, broader state of consciousness. This state is essentially similar to the concentration of a Dongba priest during rituals. Therefore, it is a spiritual experience ultimately achieved through intellectual guidance.

When viewers encounter The Road to Heaven at Lisson, how would you like them to respond? Should they see it as a cosmological map, a spiritual meditation, or simply as painting?

Ding Yi: Will the reactions of audiences in Yunnan and London to the exhibition be the same? I have both questions and expectations about this. I hope this exhibition can show London audiences, European audiences, a new angle – a unique response made by a contemporary artist to the themes of Dongba culture within his works.

©2025 Ding Yi