In Regent’s Park, Fatoş Üstek reframes sculpture through the lens of shadow, inviting Londoners to pause, reflect and share moments of wonder.

Fatoş Üstek sees the city not as a backdrop for art but as its stage. The Turkish-born, London-based curator has moved fluidly between biennials, public commissions and major institutions, yet it is the unpredictability of public space that continues to call her back. A sculpture in a park, she says, can “shift perception, even if only momentarily”.

As curator of Frieze Sculpture through 2026, Üstek is reshaping Regent’s Park into an open-air museum each summer. This year, she introduced a theme for the first time: In the Shadows. For her, shadow is not absence but possibility. “Shadows are thresholds: they conceal and reveal at once,” she explains. Amid overlapping crises, the idea feels urgent — a metaphor for what resists clarity and what demands collective confrontation.

The public realm is where art and life intersect most directly. It resists the containment of walls, ticketing, and expectation

Fatos Üstek

Üstek’s curatorial approach leans less on objects than on encounters. Informed by both art and science, she frames sculpture as porous, temporal and in flux, resisting the permanence that has long defined the medium. “Sculpture can be humorous, unruly, fragile; it can resist the expectation of permanence and instead lean into the reality that change is the only constant.”

That philosophy extends to her activism. Üstek is a co-founder of FRANK, a collective pressing for fair artist pay, and a founding member of AWITA, which supports women in the arts. For her, equity is not an afterthought but a foundation: the conditions under which artists work are inseparable from the art itself.

Üstek’s recent book, The Art Institution of Tomorrow, pushes the point further. She calls for cultural spaces that are open and relational rather than enclosed and monumental. Frieze Sculpture and London Sculpture Week — a collaboration linking initiatives across the city — serve as live experiments in that model, embedding art directly into the rhythms of daily life.

What Üstek ultimately seeks is astonishment and what she calls “collective wonder”. For her, that arises not from spectacle but from fleeting, shared moments: the pause of a passer-by in Regent’s Park, the glance exchanged with a stranger, the recognition that something unexpected has unsettled routine. Those moments, she says, “create a thread of connection between individuals who might otherwise remain separate”.

You’ve spent more than 20 years moving between biennials, public commissions and festivals. What keeps drawing you back to the public realm as a stage for art?

Fatos Üstek: The public realm is where art and life intersect most directly. It resists the containment of walls, ticketing, and expectation. What draws me back is precisely that unpredictability: the possibility that a passerby, with no intention of seeing art, might suddenly be confronted with a work that shifts their perspective, even if only for a moment. That porousness between art and everyday life has a potential that can unfold in shifting the way we perceive life and derive experiences.

Your practice often hovers at the crossroads of art, science and lived experience. What does that intersection offer you as a curator that a more traditional exhibition model does not?

Fatos Üstek: It allows me to think in terms of systems, processes, and encounters rather than objects alone. Science and art both bring the rigour of inquiry, lived experience brings the multiplicity of perspectives, as well as they hold space for the poetic, the speculative, the unknown.

These triangulations open new possibilities for curating beyond exhibition making, building a live field that is prone to new vantage points, frames of thinking, that is fostering experiences towards something more alive, relational, and generative.

You’ve said you want your work to spark “astonishment” and “collective wonder”. What does that look like in practice, especially when the canvas is a city park filled with passers-by who may not expect to encounter art at all?

Fatos Üstek: Astonishment often comes from the unexpected, when something interrupts the familiar rhythm of daily life and invites us to pause, to look differently. In a park, it might be a sculpture that appears to grow organically from the landscape, or one that seems to contradict it, unsettling what we think belongs there. Such encounters prompt curiosity rather than instruction; they shift perception, even if only momentarily.

Collective wonder arises when that pause is shared. It’s when strangers catch each other’s glance, both surprised and moved by what they’ve just encountered. That moment of recognition, silent, fleeting, yet profoundly human, creates a thread of connection between individuals who might otherwise remain separate.

This is one of the reasons I titled this year’s edition of Frieze Sculpture around the idea of shadows. I believe we urgently need spaces for collective wonder: to sit with ambiguity, to share silences, to contemplate not only what delights us but also the shadows we grapple with, the fears we carry, the ghosts that haunt us. Autumn amplifies this experience as shadows lengthen, light passes through the thinning canopy of leaves, and the sculptures are cloaked in moving blankets of light and shade. In that shifting atmosphere, astonishment and wonder become not only individual experiences but collective ones, binding us together in ways no screen or solitary encounter ever could.

Courtesy of the artist and CLOSE Gallery

For the first time, you’ve given Frieze Sculpture a theme: In the Shadows. Why introduce that framing now, and what do shadows allow us to see — or to imagine — that light does not?

Fatos Üstek: Shadows are thresholds: they conceal and reveal at once. In times of uncertainty, shadows remind us that not everything is visible, not everything illuminated and yet the unseen can be just as powerful.

This theme feels urgent now, as we navigate overlapping polycrisis. We are building new frameworks of understanding, new ways of orienting ourselves as humans on this planet: from interspecies awareness to developing less extractive, less consumerist relationships with resources, and toward a form of interconnectedness grounded in sensitivity. Shadows embody what feels most present in this moment, and also what frightens us. We fear the darkness around us as much as the darkness within. Yet this is not a time to fear other people, actions, or ways of being; it is a time to collectively face the demons that hunt us and the ghosts of the past that haunt us. We are not simply on the verge of a paradigm shift; we are in its belly. Change has already begun, reaching into the most sensitive and receptive parts of our lives.

This year’s exhibition seeks to carve out a space of bravery, to walk into the shadows we usually try to avoid. Shadows are also a silent yet central pillar of art: especially in painting, sculpture, and moving image.

Renaissance painters wrestled with shadows, resisting them, yet relying on them to build perspective. In myth, shadow is said to be the origin of both painting and sculpture, the first drawing made from the outline of a loved one’s shadow, the first sculpture born from that contour. Sculpture has since carried this umbilical attachment to the human scale. From sovereign states to psychogeographies, shadow occupies the terrain of shame and guilt, demanding recognition and, perhaps, friendship. In Frieze Sculpture, we encounter many nodes and nuances of human impact, on one another and on other living beings, through violence, extraction, and care.

I want to encourage all visitors to dwell in ambiguity, to look again at what slips from view, and to imagine what lies beyond the obvious.

Regent’s Park is a manicured, deeply English landscape. How do you reconcile that setting with contemporary sculptures that can be humorous, unruly or even confrontational?

Fatos Üstek: Regent’s Park is indeed a manicured, deeply English landscape: controlled, orderly, and steeped in tradition. To set contemporary sculpture within it, is to introduce a kind of productive friction. The sculptures, whether humorous, unruly, or confrontational, act as interruptions to that cultivated order, slipping shadows into a polished surface. They remind us that beneath manicured landscapes, whether parks, cities, or even societies, there are layers of history, exclusion, and desire that cannot be so easily contained.

Autumn, too, deepens this dialogue. It is the season when shadows lengthen, when light passes through the thinning bodies of leaves and the whistle of the wind, casting shifting veils across the works. A blanket of light and shade moves across their surfaces, drawing attention to their presence in ways that summer brightness or winter starkness cannot.

This tension between order and unruliness, clarity and obscurity, is precisely what makes the encounter vital. The park offers a frame of comfort and familiarity, and within it, the works open thresholds: they conceal and reveal, disturb and reorient. Just as shadows complicate light, the sculptures complicate the landscape, asking us to imagine what lies beyond the obvious. In this way, the manicured setting is not a contradiction but a stage against which contemporary voices can resonate all the more powerfully.

Sculpture has traditionally been thought of as fixed and monumental. Yet you often emphasise play, humour and impermanence. How are you reimagining what sculpture can be in the 21st century?

Fatos Üstek: Sculpture has indeed carried a long history of being fixed, monumental, and permanent. Yet in the 21st century, I see it as something porous, temporal, and in flux, able to respond to the urgencies of our time. Monumentality, after all, is not the only way to inscribe meaning. Sculpture can be humorous, unruly, fragile; it can resist the expectation of permanence and instead lean into the reality that change is the only constant.

Play and humour are vital forms of resistance, lightness can puncture heaviness, just as shadows complicate light. Impermanence reminds us that nothing is static, that we live within shifting ecologies and fragile systems. To me, sculpture in this sense is less about monumentality and more about experience, resonance, and relation. It becomes a threshold through which we consider our connections: human to human, human to other beings, human to place.

We live in a moment when so much cultural life unfolds on screens. What can a sculpture in a public square or a park offer that no digital encounter ever could?

Fatos Üstek: Embodiment is at the heart of it. We live at a time when so much unfolds on screens, disembodied, flattened, endlessly reproducible. The work exists in scale and proportion to our own bodies; its textures, surfaces, and materials speak directly to touch, even when we do not physically touch them. Light shifts across them hour by hour, day by day, season by season. This is not only a matter of perception but of relation. To stand before a sculpture is to share space with it, and with others who are drawn to it.

Public sculpture gathers us, makes us aware of our own embodied presence in the world, and asks us to notice the interdependence of place, material, and human scale. No screen can replicate the sensory, spatial, and temporal richness of that encounter.

London Sculpture Week is unusual in its scope — it brings together Frieze Sculpture, The Line, Sculpture in the City, the Fourth Plinth and East Bank. What does this citywide conversation make possible that individual projects can’t achieve on their own?

Fatos Üstek: It forms a chorus rather than a solo voice. Each initiative carries its own character and rhythm, yet together they compose a city-wide encounter with sculpture. This breadth allows Londoners and visitors to experience multiplicity, to witness how diverse contexts, curators, and artists resonate with one another.

The city itself becomes a stage for dialogue, with each neighbourhood, park, and square adding its own inflection to the larger composition. This spirit of collaboration also reflects the values of our century, where working together is not only desirable but essential for our shared existence and survival.

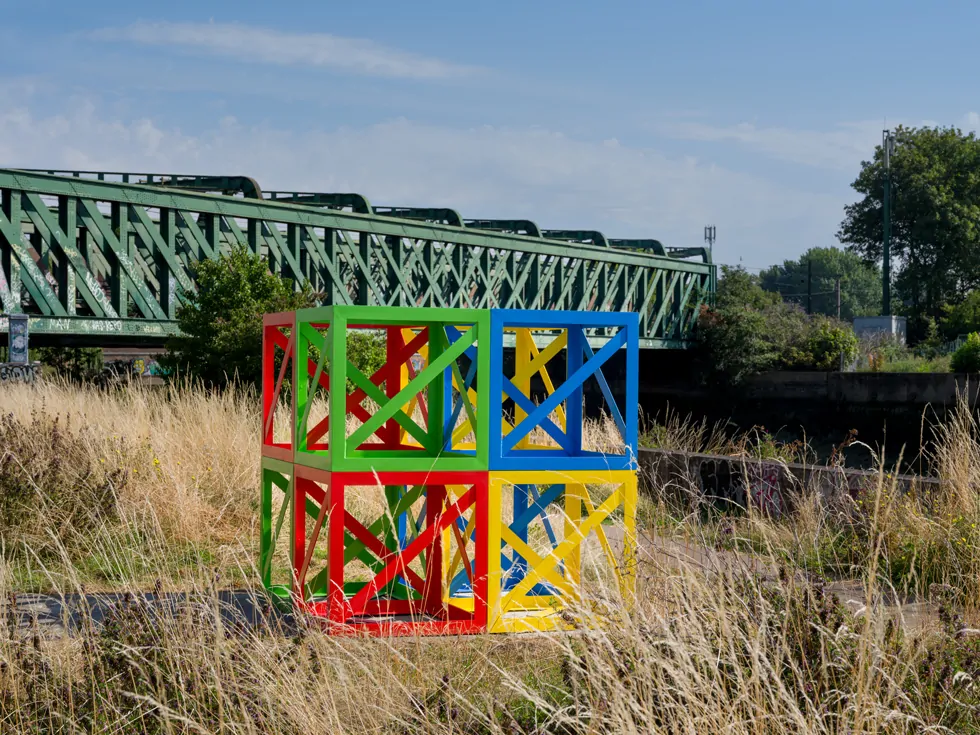

Photography by Angus Mill.

Courtesy of The Line

The week spans very different voices — from Rasheed Araeen’s minimalist interventions to Teresa Margolles’s tribute to trans and non-binary lives. How do you imagine those works speaking to one another across London?

Fatos Üstek: Their dialogue is not linear but resonant. Araeen’s work foregrounds structure and space, offering clarity and rhythm, while Margolles bears witness to lives erased and silenced, demanding recognition and mourning. Placed across the city, their works do not compete but echo, reminding us that sculpture can hold both abstraction and deep social urgency. I also add Jaune Quick-to-See Smith to this constellation. In her Trade Canoe series, she blends beauty, tradition, and political satire.

For example, King of the Mountain, 2024–2025 included in Frieze Sculpture this year speaks of colonial histories, environmental damage, and the health crises imposed on Native communities. The canoe carrying the statue of the last born bison at their trench in Montrana US, is a traditional symbol, becoming both vessel and witness.

In your recent book, The Art Institution of Tomorrow, you call for reinventing the model of the art institution. Do you see experiments like Frieze Sculpture or London Sculpture Week as part of that reinvention?

Fatos Üstek: They are part of the approach that informs my model. These projects are not bounded by walls or collections but by networks of people, ideas, and practices. They are porous, temporal, and embedded in the fabric of daily life. They activate public space, invite accidental encounters, and bring art into relation with light, weather, and season. If we are to reinvent institutions, they must move toward this kind of openness, away from enclosure and toward encounters, exchange, and relevance.

You’ve also been vocal about equity and fair pay through FRANK and AWITA. How do those commitments shape the choices you make as a curator, and what might a more equitable future for public art look like?

Fatos Üstek: Equity and fairness are not supplementary; they are foundational. As a curator, I ask not only what work is shown, but under what conditions, and with what care for the artist.

A more equitable future for public art means institutions committing to fair pay, transparent contracts, and genuine collaboration. It also means ensuring that artists from diverse backgrounds and perspectives have access to the stage of the public realm, so that the multiplicity of society is reflected in its art. Public sculpture is not only about presence in space; it is about who is granted that presence, and under what terms.

©2025 Fatos Üstek