British curator Ben Tufnell on slowing down in the age of acceleration, curating with integrity, and finding poetry in the landscape.

By the time Ben Tufnell begins talking about mud, you realise he isn’t really talking about mud at all. He’s talking about the way time slows when you’re truly looking, about the humility of materials, and about art’s ability to resist the acceleration of the world. A British curator, writer, and editor, Tufnell was the director of Parafin, the independent London gallery he co-founded. Parafin’s chapter came to a close last year after ten years of shaping conversations around contemporary art.

Tufnell’s career spans more than a hundred exhibitions in partnership with institutions from Tate Britain and Tate St Ives to Yorkshire Sculpture Park and museums in Mexico, South Africa, and Scotland.

Courtesy of Ben Tufnell © Ben Tufnell

The lessons I learned were to look carefully, to take my time, to resist the temptation to jump to conclusions

Ben Tufnell

He has moved between the deliberate pace of major museums and the quicker metabolism of commercial galleries, always with a steady focus on work that inhabits the territory between landscape and abstraction, between place and perception.

Raised on a smallholding in rural Norfolk and drawn to mountaineering, Tufnell’s sensibility naturally leans towards art rooted in land and nature. His curatorial projects — from the landmark Uncommon Ground: Land Art in Britain 1967–79 to his new exhibition After Nature at Somerset Close Gallery — often combine elemental materials such as ash, ochre, or river mud with contemporary strategies and technology, prompting us to see both the natural world and our place within it anew.

The through-line is a commitment to aesthetic experience as the primary encounter, with intellectual and thematic layers following in its wake. His exhibitions, whether pairing emerging painters with established names or staging quiet works alongside monumental ones, are built as conversations — each artwork given its own space to speak, allowing ideas to emerge organically rather than through overt direction.

With After Nature, Tufnell brings together artists responding to ecological collapse without slipping into didacticism. Urgency is balanced with openness; polemic yields to poetry. What stays with him — and, he hopes, with audiences — is not work that resolves itself immediately, but the kind that remains slightly beyond reach, inviting return visits over days, weeks, or even years.

Here, he reflects on aesthetic primacy, balancing voices across generations, and why ambiguity can be more powerful than certainty.

After Nature: Curated Ben Tufnell opens on the 13th of September until the 25th of October 2025 at CLOSE

You’ve curated over a hundred exhibitions across major institutions and independent galleries. Looking back, how would you define the core principles that guide your curatorial decisions, regardless of scale or venue?

Ben Tufnell: I guess that when I’ve been able to make choices (because as an institutional curator you are often assigned projects rather than choosing them) I’ve been guided by a sense of integrity in the work. I want to work with artists who have something meaningful to say and have developed an interesting way to say it. Certain kinds of work speak strongly to me because of my personal history and background. For example, I’ve always gravitated to work about land and nature and I think that’s in part due to growing up on a back-to-the-land style smallholding in rural North Norfolk and also because of my love of mountaineering. But I’ve also always been fascinated by painting, which seems to be almost infinite in its possibilities.

Your work often bridges art, landscape and ecology. How do you balance thematic depth with aesthetic experience when designing an exhibition?

Ben Tufnell: This may be a rather old-fashioned position but for me the aesthetic experience is primary. It’s the first consideration. Hopefully, by making careful selections, it’s possible to make a rich and thought-provoking exhibition that is also aesthetically intriguing.

© Ben Tufnell

When working with both established names and emerging voices, how do you ensure each artist’s work speaks to the larger narrative without being overshadowed?

Ben Tufnell: It’s a balancing act. Strong work can hold its own, no matter the age (or status) of the artist. Nonetheless, as a curator one must make careful choices. Interestingly, I find that while younger artists are keen to show alongside established figures, senior artists also want to see their work alongside the younger generation. In each instance, the context offers new ways of seeing the work.

You’ve spoken about the “slow time” of painting. How do you see that concept resonating – or resisting – in an art world driven by rapid consumption and short attention spans?

Ben Tufnell: In our accelerated culture anything that gives us pause and slows us down is increasingly important. Good art can do that. The art world now – and indeed the wider culture too – is fixated on momentary engagement, and I can’t help but feel that something important has been lost. I love the way a painting can reveal itself gradually over time. If you’ve had the good fortune to live with an artwork, or regularly revisit a favourite painting in a public collection, then that revelatory experience doesn’t just last seconds but can extend over minutes, hours, weeks, even years.

Do you think a great exhibition should leave the audience with answers, or with more questions?

Ben Tufnell: Definitely the latter. For me it’s the art that you don’t immediately fully comprehend, the work that nags at you, that is the most powerful. That’s the stuff that stays with you. A lot of overtly political work can feel reductive, perhaps because it doesn’t offer any mystery, but rather deals in certanties. Again, it might be an old-fashioned position but I love art that embraces a sense of ambiguity. Not everything has to be black or white. There are infinite shades of grey.

Your tenure at Tate Britain included significant exhibitions that shaped contemporary understandings of British art. What lessons from that period still influence your independent curatorial work today?

Ben Tufnell: When I was working at Tate Britain I was acutely aware of the responsibility. In a way, in a canonical institution like that, you’re playing a (very small) role in the writing of art history. That said, I think that since then I’ve come to understand that there are actually many art worlds, many art histories. In a way we each make our own art world, our own art history. Again, shades of grey.

The lessons I learned were to look carefully, to take my time, to resist the temptation to jump to conclusions. An idea of rigour, I suppose. Also, the importance of communicating with clarity. When writing display captions, you have just 150 words to give the audience a meaningful insight into a work of art. That’s a good discipline to learn.

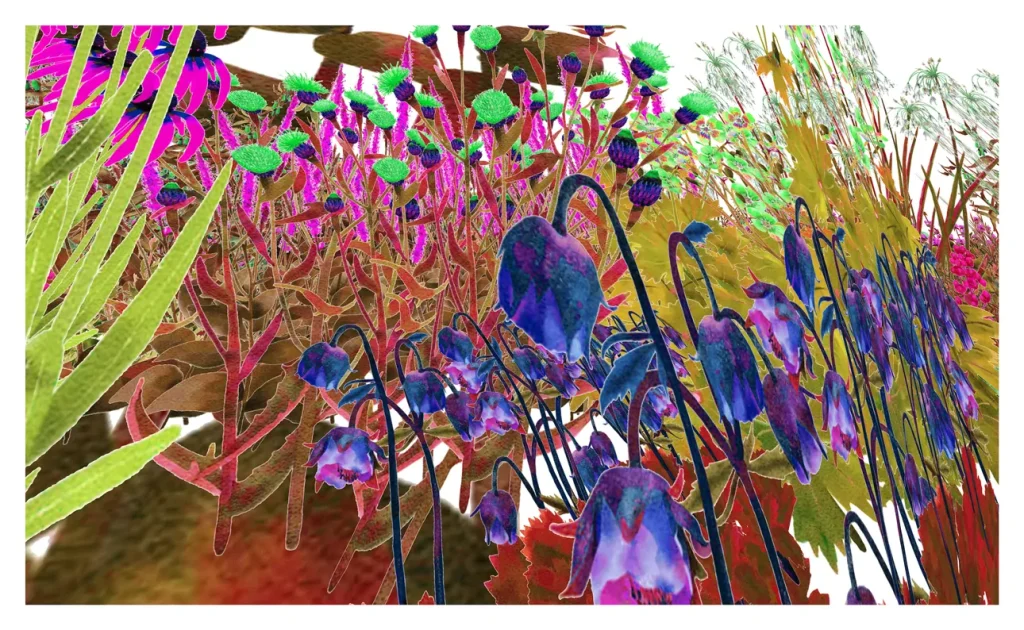

Courtesy the artist and CLOSE Ltd.

Tate Britain is often positioned as a guardian of national art history. How did working there affect the way you approach contemporary and experimental work now?

Ben Tufnell: I think as a museum curator you learn to view contemporary work through the lens of history, to understand how things fit into a bigger and broader picture. Artists are always in conversation with the past, even if they’re trying to break with it and forge something new.

Having moved between major institutions such as Tate Britain and independent galleries, what freedoms do you find in the independent space that aren’t possible in larger institutions?

Ben Tufnell: Museums are slow. It can take years to get from the beginning of a project to the opening. It means you can be really rigorous, do the research, do the thinking, let things mature. But in commercial galleries you can be quicker, more responsive, looser, less bound by institutional protocols and responsibilities. You can make things happen. But of course, if you’re moving quickly you’re losing that space for reflection. So there are positives and negatives to both scenarios.

And in a commercial gallery one does have to consider the marketplace. The reality is that a commercial gallery has to sell the art it exhibits to survive, to pay the rent, to support the artists it represents. Somewhat idealistically, working in that commercial context, I always wanted to believe that if you show great work and make strong exhibitions, the sales will take care of themselves. Sadly, it’s not always true.

Conversely, are there resources or structures from the institutional world you wish you still had access to?

Ben Tufnell: Not really. I’m very grateful to have had the experience of working at Tate, but I’ve felt liberated working in the commercial sector, despite the pressures.

After Nature engages with the idea of creating art “after” nature – both in imitation and in the shadow of ecological crisis. How did you develop this conceptual framework, and how did it shape your artist selection?

Ben Tufnell: It’s a show I’ve been thinking about for a long time. It’s hardly a new idea – artists have been making work like this, using natural materials and processes, for decades, in particular since the 60s and 70s with the development of Land and Conceptual art and Arte Povera – but right now it feels very timely. This is definitely a show both for and about the present moment, an exhibition for a time of environmental collapse, for a quickening emergency. I’ve been able to include some artists I’ve worked with before, at Parafin and Haunch of Venison, some associated with CLOSE, and some great artists I’ve wanted to work with for some time.

Some works in the show directly use natural materials or processes – mud, ash, ochre, evaporation – while others use technology to simulate non-human perception. What conversations emerge when these approaches share the same space?

Ben Tufnell: Hopefully, these differing and contrasting approaches can offer us new perspectives on our relationships with nature. To see work made with such disregarded and overlooked materials as mud, algae or charcoal, to visualise a bees-eye view of pollinator-friendly planting schemes, perhaps these strategies can offer us new perspectives, help us to reevaluate the way we ascribe value, even help us see the world around us anew.

Ecological art can risk becoming overly didactic. How do you keep the work open and nuanced, allowing for poetry and ambiguity rather than polemic?

Ben Tufnell: I agree that much ecological art falls into that trap. I’ve tried to avoid it in this show, to select work that is open – that suggests a position, asks a question, rather than offering definitive solutions. Ecology is obviously a key theme that runs through the show but none of the work is polemical. It’s not a campaigning exhibition.

Rather, it quietly and insistently asks us to look again at nature. Beautiful works made from humble materials; a study of the ways in which the leaves on an oak tree change colour with time; tracing the shifting shadow of a rock as the sun crosses the sky over the course of a day; these things can offer us unexpected insights, hopefully leading to a renewed appreciation of the present moment and the predicament we face.

Several featured artists, such as Aimee Parrott and Nissa Nishikawa, are at earlier stages in their careers. How do you identify emerging artists whose practices can hold their own alongside figures like Richard Long or David Nash?

Ben Tufnell: It’s an interesting question and it’s really just about the quality of the work, I think. You see the work and have a gut feeling, an emotional response, an intellectual reaction, you do a studio visit, you ask questions, listen and try to understand the artist’s position. And then you make a selection that doesn’t overly prioritise one artist – a big name, perhaps – over another.

The mud piece by Richard Long we have in After Nature is huge, yes, and is shown alongside paintings in ochre and copper waste by Onya McCausland and work using Thames river mud by Mercedes Balle and they more than hold their own. They’re all in conversation. The pastel works by David Nash – a new series charting the shifting colours of leaves and foliage through the seasons – are rather modest and are paired with new paintings by Fred Sorrell. These juxtapositions create a series of really interesting dialogues across the generations.

Photo courtesy of Catherine Repko

© Catherine Repko

Are there any lesser-known artists – perhaps not in After Nature – whose work you think deserves urgent attention right now?

Ben Tufnell: Three younger artists I’ve been looking at and thinking about recently, all making completely different kinds of work, are Silke Weissbach, Karima Al-Mukhtarova and Catherine Repko. Silke makes very interesting paintings that combine organic materials with the hyper-artificial products of the beauty and cleaning industries; softeners, varnishes and so on. The resulting works are beautiful abut have something uncanny about their surfaces that you can on really see in person.

Catherine Repko, who shows with Huxley-Parlour, is a figurative painter. She makes seemingly simple, yet intimate, subtle, meditative paintings about her family. They feel like slow works and are all the better for it.

Karima, who is based in Prague and who has not really exhibited in the UK yet, makes works with glass, thread, clay and fabric. She has a very powerful photographic series called CONNECTION ALMOST FOUND in which she stitches words or phrases into the skin of the palms of her hands.

In your experience, what distinguishes an exhibition that lingers in the cultural memory from one that disappears once the doors close?

Ben Tufnell: It’s impossible to say. It’s that unknowable and unpredictable combination of factors that somehow create an emotional connection with an audience. I’m hopeful that After Nature might linger a little.

©2025 Ben Tufnell