The photographer who quietly chronicled the Black Panther Party’s radical vision—capturing not just protest, but care, community, and the power of bearing witness.

History doesn’t always reside in textbooks. Sometimes, it unfolds in the streets—through the posture of protest, the uniform of resistance, the stance of a person confronting state power.

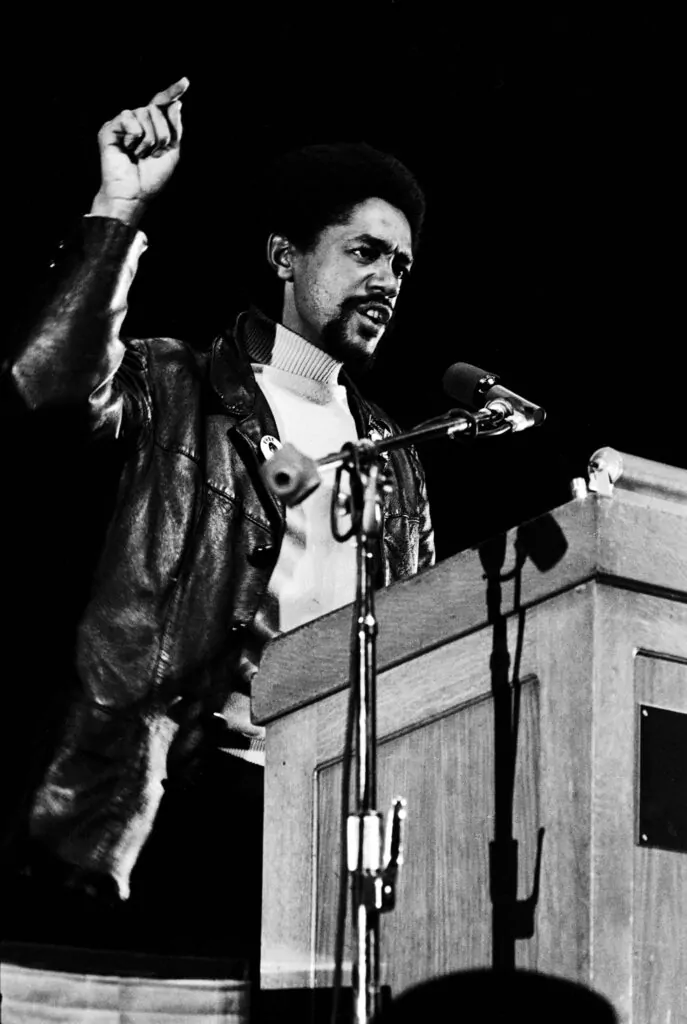

In 1966, in Oakland, California, Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton co-founded the Black Panther Party, introducing a new visual and ideological language of resistance. What began as a local patrol to monitor police violence quickly expanded into a national movement rooted in self-determination, mutual aid and political education.

Credit Joshua Shames

Photojournalists must document the world in as truthful a way as we can

Stephen Shames

Alongside them, behind the lens, stood a young university student with a camera—Stephen Shames. As the Panthers marched, fed, taught and resisted, Shames documented, transforming observation into testimony. White and just 20 years old when he began photographing the Panthers in 1967, Shames was granted uncommon access to the inner workings of a movement often misrepresented—or reduced—to its most militant images.

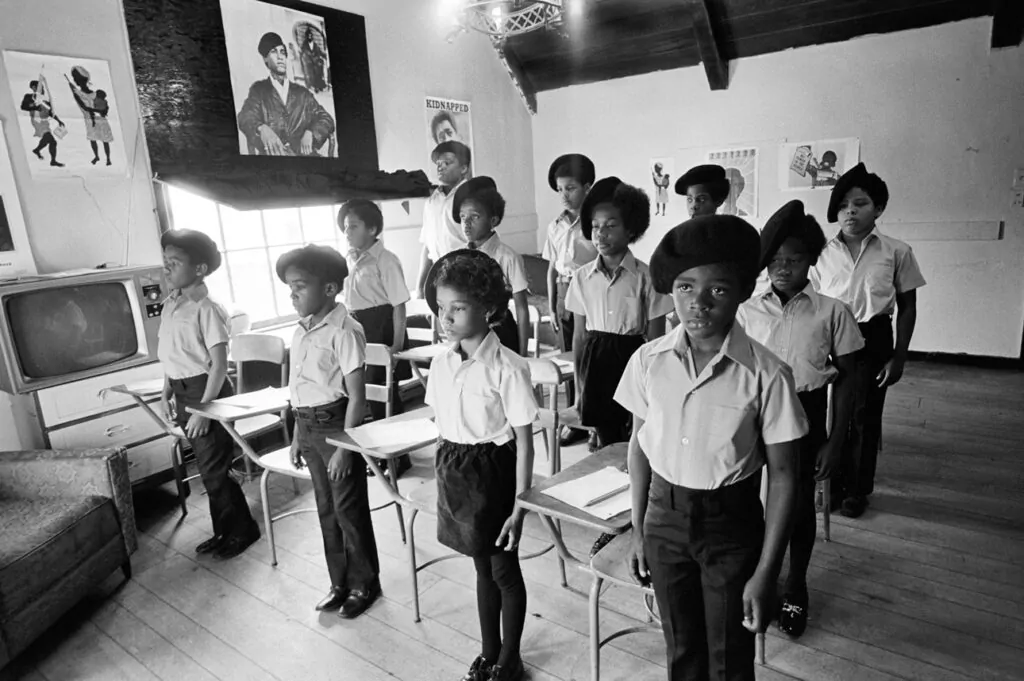

Over the next six years, he compiled one of the most vital visual records of the Black Panther Party. His photographs captured public demonstrations and intimate, often overlooked moments: children receiving free breakfasts, women mapping political strategy, members teaching community classes and building neighbourhood clinics. These images offer a powerful counter-narrative to mainstream portrayals—showing more than the Panthers’ radical posture but the radical care that sustained their communities.

Now in his seventies, Shames has spent more than five decades documenting the margins of American life. His camera has chronicled poverty, racial injustice and youth in crisis—across the United States and abroad. Yet his approach has remained consistent: observe, listen, build trust. ‘Listen first, shoot second,’ he says.

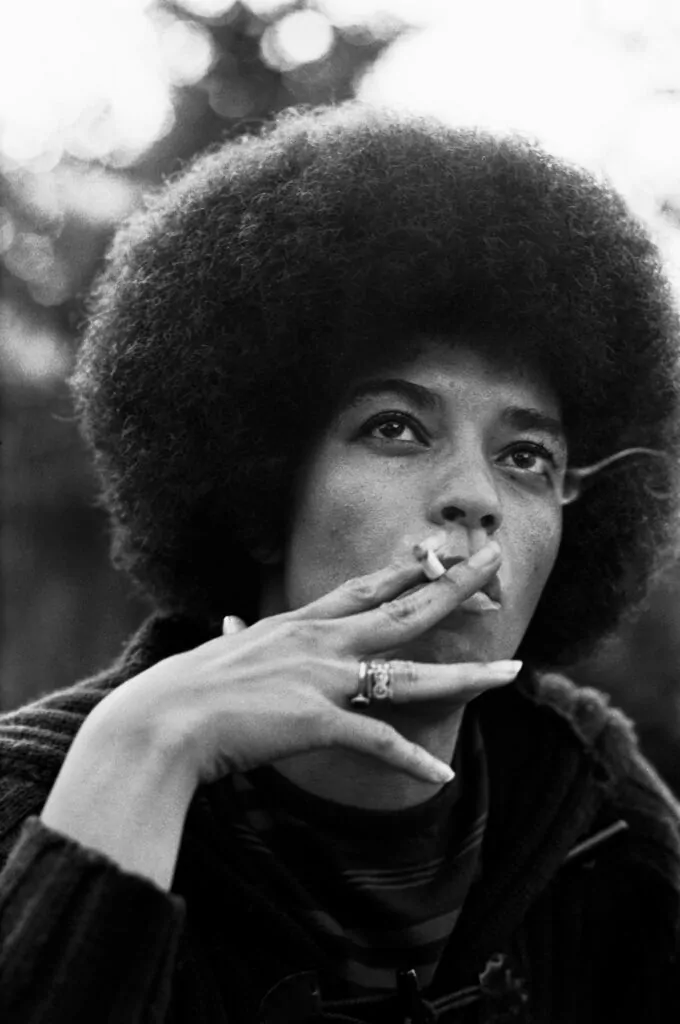

From 1967 to 1973, Shames watched the Panthers evolve from a grassroots defence group into a national symbol—at once feared, surveilled, and deeply rooted in the communities they served. His archive gives texture to the headlines, drawing attention to the people behind the politics. Women, in particular, emerge as central figures: organising, leading, sustaining the Party’s day-to-day work.

In 2006, Shames extended his activism beyond photography. He founded an NGO supporting marginalised children in Africa—AIDS orphans, former child soldiers, displaced youth—helping them access education and build futures in leadership and service. In 2010, he was named a Purpose Prize Fellow by Encore.org.

He is the author of eleven photographic monographs and a zine, including Stephen Shames: A Lifetime in Photography (Kehrer Verlag, 2024) and Comrade Sisters: Women of the Black Panther Party (ACC Art Books, 2022), co-authored with former Panther member Ericka Huggins. This May, his archive receives its first major UK showing with Black Panthers & Revolution at Amar Gallery in London. The exhibition presents work that feels less like a historical collection and more like a timely mirror.

At a moment when questions of racial justice, inequality and civic unrest once again shape public discourse, Shames reflects on the power—and the limits—of the photographic image. His message is clear: photography may not, on its own, change the world. But it can help us see one another more truthfully.

Because now, as then, the question remains: how do we see one another—and who holds the lens when power looks away?

Black Panthers & Revolution: Stephen Shames opens on the 29th of May, 2025 until the 6th of July, 2025 at Amar Gallery, Kirkman House, 12-14 Whitfield Street, London, W1T 2RF

You had extraordinary access to the Black Panther Party from 1967 to 1973. What was it like being a white university student in such close quarters with this revolutionary Black political group, and how did that shape your understanding of race and solidarity?

Stephen Shames: I know this may sound weird to most people – especially those on the left and right, who are concerned with race and ethnicity, but I never really thought about it. . I never felt “out of place” or an “outsider” with the Panthers or in the Black community. (The Black community is very welcoming to everyone.)

The Panthers for their part, is open to all who are part of the struggle. The Panthers formed coalitions with many people and groups, including the Young Patriots, whites from Appalacia who lived in Uptown in Chicago. They also formewd alliances with Asian, Native Indian, Puerto Rican (The Young Lords), and Latino groups.

at the first national United Front Against Fascism conference. Oakland Coliseum

© Stephen Shames

Image courtesy of Amar Gallery

Many of your images reveal a softer, more human side of the Panthers—childcare, education, community meals. Was this a conscious counter-narrative to the media’s portrayal of them as militant and dangerous?

Stephen Shames: Yes, my photos provide a counter narrative to the governemnt’s and media portrayal of the Panthers. But it did not start out as a concious counter-narrative. I just photographed what I saw and experienced. My goal as a photographer has always been to find the “truth”, to delve deeply into a topic and document what I learned. The Panthers had incredible survival programs (60 in all) and were just people trying their best to create a better, more just world.

© Stephen Shames

Image courtesy of Amar Gallery

In Comrade Sisters, you spotlight the often-overlooked role of women in the Black Panther Party. How did these women reshape your understanding of leadership and resistance?

Stephen Shames: Women comprosed around two-thirds of Panther Party members. They were the backbone of the Party. Womern ran most of the programs. The Black Panthers were the most progressive organization at the time. Most of the anti-Vietnam war leaders and leaders of left-leaning organizations, for example, were men. The Panthers had women on the central committee; and women at all levels.

Your book Outside the Dream was one of the first to spotlight child poverty across America with such clarity. What surprised you most in those early years of travelling across the U.S. to document children in poverty?

Stephen Shames: What surprised me most was that these children and their families were survivors; not victims. The poor are often portrayed as lacking skills. (Culturally deprived was a buzz word back then.) But the poor are mostly people living in communities without resources. They lack opportunity, not ambition.

© Stephen Shames

Image courtesy of Amar Gallery

You’ve spent decades photographing children living through trauma—in the U.S., Brazil, Romania, and Africa. How do you build trust with vulnerable young subjects, and what does ethical storytelling look like when the stakes are so high?

Stephen Shames: Trust is build by listening and being open. Ethical storytelling is telling the truth.

With Pursuing the Dream, you chose to photograph not just struggle, but solutions. How do you frame hope without drifting into sentimentality or undermining the seriousness of the issues?

Stephen Shames: Pursuing the Dream focused on community solutions to poverty. The sub-title of the book is “What Helps Children and Their Families Succeed”. That is the key. People, if they have the right tools are capable of solving their issues. Most media portayals of solutions to poverty focus on rich benefactors who help the poor. This is a colonial model. The wonderful rich person (or country) has to help the poor, inferior victims. Pursuing the Dream focused on the poor communities themselves and showed how with resources and a framework, children succeed.

Youth Institute, the Black Panther school

© Stephen Shames

Image courtesy of Amar Gallery

In 1986, you testified before the U.S. Senate on child poverty. What did that moment teach you about the limits—and the potential—of visual storytelling to drive political action?

Stephen Shames: The limits of storytelling to affect social change is that while visual images are powerful and touch our emotions — photographs can not change things by themselves.

That is why I partnered with organizations that had the resources to use the photographs as[part of their campaigns to effect change. The Children’s Defense Fund co-published Outside the Dream: Child Poverty in America and used the photos to awaken people to the millions of children living in poverty in the richest nation in history.

Family Support America partnered with other organizations to use the images in Pursuing the Dream to show how community organizations were helping poor communities. The photos documented real, practical approaches that worked — and were cost effective. The photos got people’s attention. Their text and documentation, along with their lobbying and publications provided the proof. Among other things, they organized exhibits of the photos in the rotundas of as number of state legislatures so the politicians saw the photos as they were considering their state budgets.

© Stephen Shames

Image courtesy of Amar Gallery

Your exhibitions with Amar Gallery, including Black Panthers & Revolution, marked your first major gallery show in London. What did it mean to present that body of work internationally, especially at a time when civil rights struggles are again front and centre globally?

Stephen Shames: This is the first exhibit of my work in the United Kingdom. There have been exhibits in France, Japan, and the United States. It is important that images like these are exhibited everywhere since civil rights are under attack in many places.. As President John F. Kennedy said many years ago, “Our problems are man-made, therefore, they can be solved by man.” Racism is a problem created by humans. Hopefully these photographs will offer hope that we can fight back and “solve” poverty and racism.

© Stephen Shames

Image courtesy of Amar Gallery

You’ve said your work is about listening more than observing. How does that philosophy shape what you shoot—and what you choose to leave out?

Stephen Shames: It is important to listen to the people you are photographing — especially if they are from a community that is not your own. Everyone lives in a cultural bubble. Photographers have to get outside their bubbles and undertand how the people they are ducmenting see things.

Merely observing from inside your bubble — with the point of view of your cultural world does not get you inside the community you are photographing. You need to listen so you understand the people you are photograhing. You must get inside their community so you are able to see things from their point of view, as well as, your own.

Looking at today’s movements—like Black Lives Matter or youth-led climate action—how do you see the role of the photojournalist evolving in a world of instant images and curated feeds?

Stephen Shames: Nothing has changed in terms of our job. Photojournalists must document the world in as truthful a way as we can. What has changed is how the images are seen and distributed. It is always a struggle to get the photos out there and to get them seen.

Image courtesy of Amar Gallery

After more than five decades of bearing witness to inequality, resilience, and revolution, do you feel more hopeful or more heartbroken about the world you’ve captured?

Stephen Shames: In the 1960s and 1970s we were hopeful and optimistic we could create a better world. In 2025 and beyond, as we face the consequences of global warming, the next 50 years are going to be devastating even if we got to zero temperture increase tomorrow. Today I hope humanity (and the animals and plants) survive the greed and recklessness of those with money and power.

©2025 Stephen Shames