In a time when so much contemporary art has turned to narcissistic celebrations of the self—self-portraits (look at me!), narratives of the artist’s life (look at me!), or simple sensationalist pranks (look at me now!), how refreshing it was to come across the ceramic structures of Ayten Turanli, an artist whose works are a celebration, rather, of art.

Born in Turkey in 1951 and now living and working between Istanbul and London, Turanli straddles the lines between contemporary art and traditional craft-making; between sculpture and painting; between art as form and art as idea—or both.

In her exhibition Resonance at London’s Pi Artworks (January 7 – 21, 2025), the artist’s explorations of ceramics as a historical material (chiefly as tiles, an essential aspect of Ottoman art, design, and architecture) and as a universal sculptural material (think of ancient Greek vases, Mayan ceremonial figures, or artists like Auguste Rodin and Edmund de Waal) offer dialogues about the nature of the material as an art form and the integration of art itself into the minutiae not just of daily lives, but of history.

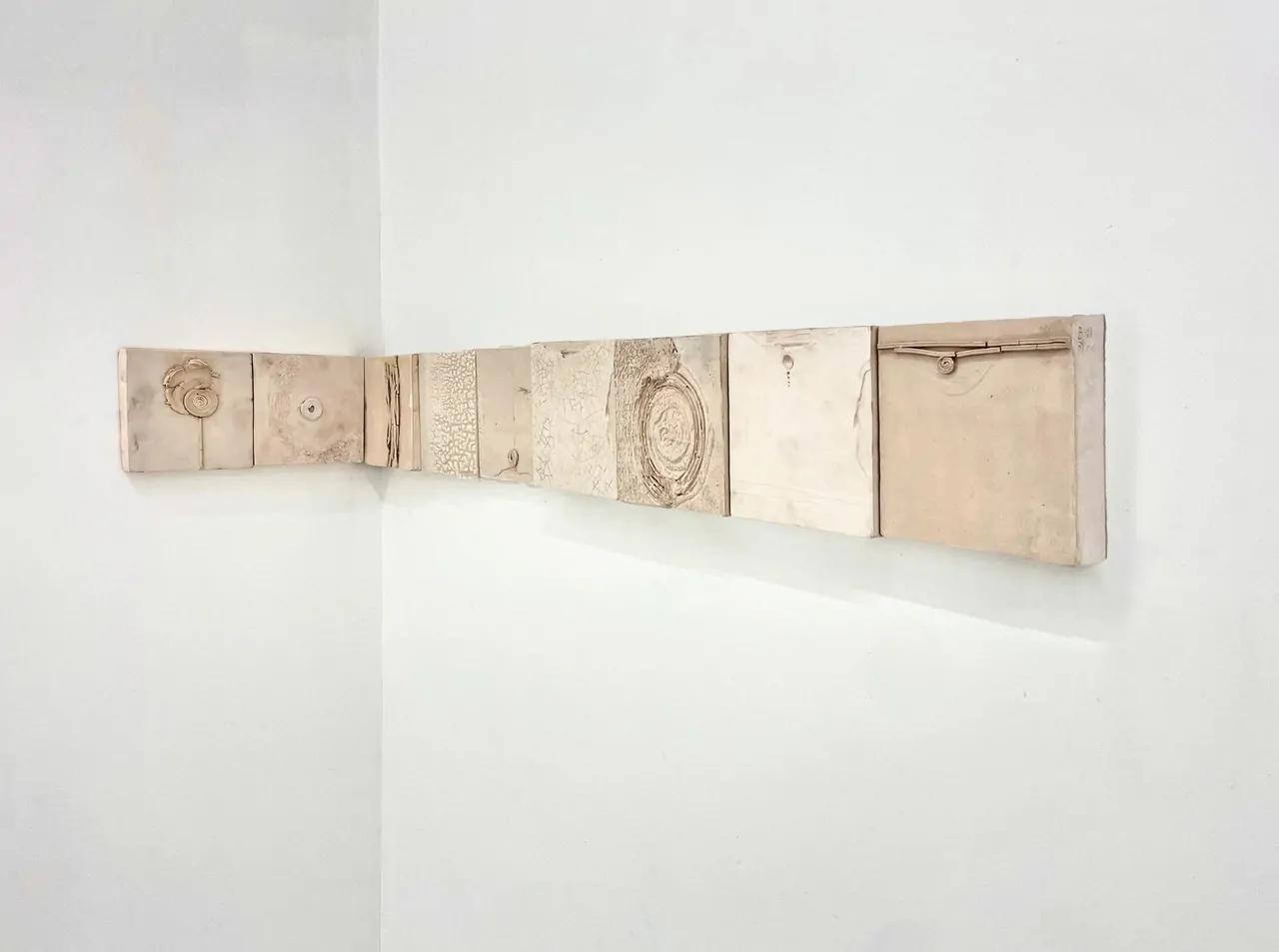

Installation view

Image courtesy of Pi Artworks

Hence, large 103-centimeter columns of stacked 5-millimeter glazed stoneware tiles, each individually formed to bend and wave, create horizontal patterns of line and color that contrast with the strict uniformity of the vertical stack, which is held within a stainless steel frame. (Movement within a confined space, perhaps? An allusion to the restricted role of women who create? After all, in most cultures, it is traditionally women who produce tiles, earthenware, and other ceramic objects necessary for survival, if not aesthetics.) The dark hues, the sensuous waves, invite touch, pique curiosity: is there something hidden there—a secret message, perhaps, a treasure, held within?

Installation view

Image courtesy of Pi Artworks

Hence, too, the square compositions comprised of minuscule cube-shaped tiles, each at a different height and framed in black-painted wood, hanging along a wall. Are they sculptures, or are they paintings made of clay? Does it matter? Or is this the kind of question art intrinsically demands?

Why Clay? Why Art?

I am reminded of an anecdote related to me once by the great curator Rudi Fuchs. At the opening of an exhibition of works by Jannis Kounellis that involved objects like piles and sacks of raw coal, a visitor approached Fuchs with a question:

“It’s a nice exhibition,” the visitor allowed. “But tell me: why coal? Why the sacks of coal?”

Fuchs, as usual not missing a beat, replied, “Why oil paint?”

“Why oil paint?” Why clay? Why marble? Why form? Why color? Why dimensionality—or not? How much of the frame of a piece is frame, and how much is the work itself? Are the tiles within, then, brushstrokes of a kind?

Does it matter?

A Celebration of Art Itself.

Installation view

Image courtesy of Pi Artworks

These are the questions great art asks, inspiring our imaginations to search further and explore deeper.

This is what Ayten Turanli does in her work.

We need so much more like this.

Abigail Esman, New York, April 2025

©2025 Abigail R. Esman, Pi Artworks