British artist Pogus Caesar‘s path into photography wasn’t just a change in medium but an evolution in how he chose to tell stories. Having travelled across the UK, Spain, India, South America, Sweden, Denmark, South Africa, Albania, and Jamaica, his work documents prominent figures and historical events.

Starting as a pointillist painter—an art form that demands patience and precision—these early beginnings nurtured Caesar’s meticulous eye for detail and his reverence for capturing the authenticity of life.

Credit Derek Bishton

I have always enjoyed working with black-and-white film, particularly 35mm at 400asa for its grain and how it connects with the eye

Pogus Caesar

During his visit, Caesar wandered into a bookshop and discovered a monograph by the late photographer Diane Arbus. Deeply impacted by the unfiltered honesty of her work, Caesar set out with renewed determination to capture fleeting moments and untold stories of the world around him through the lens of his 35mm camera.

Born on the Caribbean island of Saint Kitts in 1953 and raised in Birmingham, England, Caesar’s early life was shaped by the cadences of island life and the industrial terrain of Great Britain. In 1985, a critical point in Birmingham‘s history would change the trajectory of Caesar’s photography.

As the Handsworth riots erupted—a defiant pulse of voices clashing against the weight of poverty and marginalisation in Thatcherite Britain—Caesar was on the ground, capturing events as they unfolded. These moments would become a celebrated documentation of dignity and recognition, a refusal to be silenced amidst societal upheaval.

In addition to photography practice, Caesar’s creative endeavours encompass roles as an author, curator, archivist, and filmmaker. He was appointed director of the West Midlands Minority Arts Service in the 1980s. During this climactic era, he also became the inaugural chairman of the Birmingham International Film & Television Festival.

Caesar’s work has been exhibited extensively, from galleries to cultural institutions worldwide. Throughout the decades, he has co-curated landmark exhibitions including Into The Open with Lubaina Himid at Mappin Art Gallery, Sheffield (1984) and Caribbean Expressions in Britain, Leicester Museum & Art Gallery (1986) with Aubrey Williams and Bill Ming.

His photographs have explored cultural and social transformation in Britain from the 1980s, and the well-known Handsworth Riots 1985 has been exhibited at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London (2015), ICA, London (2021), Tate Britain (2021/2022), National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., USA (2023) and Art Gallery of Ontario, Canada (2023/24), showcasing one of the most crucial episodes in post-war Britain.

Recently, he co-curated an exhibition titled The Brighter Flame for legendary author and activist Benjamin Zephaniah, alongside art historian Ruth Millington. The exhibition featured large-scale black-and-white photographs of Zephaniah taken by Caesar himself, alongside a series of poems and photographs by both Zephaniah and Caesar from their project Handsworth 1985 Revisited. Currently, Caesar features in the group exhibition Friends in Love and War – L’Éloge des meilleur·es ennemi·es, showcasing photographs from his Schwarz Flaneur series, taken around the globe over a significant period, celebrating love and friendship.

An astute observer of human experiences, Caesar’s archive stands as one of the most important visual chronicles of Black British history—an extensive body of work that navigates the margins of society, revealing the raw and unvarnished essence of religion, sexuality, history, and identity. By capturing fleeting moments of honesty and emotion before they wilt into the ether of time, Caesar cements his role as a visual griot.

Caesar will be exhibiting in The 80s: Photographing Britain from 21 November 2024 – 5 May 2025 at Tate Britain.

Hi Pogus, thank you for joining us today, to start, could you share your journey into photography and visual arts? How did growing up in the Caribbean and later moving to Birmingham shape your creative vision?

Pogus Caesar: My creative journey really started by looking through my father’s extensive book collection, located in a cabinet at the bottom of the stairs. The images were engaging and transported me to vast and unknown landscapes.

Initially, I became a Pointillist painter, influenced by the work of Impressionist artists Georges Seurat and Camille Pissarro. The notion of painting with dots was enticing and exquisite. At the time, I could not afford canvases, paint, or brushes, so my old school fountain pens, ink, and paper were the alternative. Night after night, I would try and create my paintings; it was labour-intensive – hard on my eyesight – but utterly rewarding. As time passed, I would exhibit the work in local exhibitions at schools, libraries, and community centres. The interest those exhibitions garnered gave me the courage to continue my creative journey.

In terms of my photography practice, the pivotal moment came during a visit to New York in the early 1980s. At the time, I was using a small 110 Instamatic camera, journeying through areas like Harlem, Bronx, and Queens and snapping scenarios as I walked. When visiting a bookshop in Greenwich Village, I came across a book of the late photographer Diane Arbus. Browsing the pages, I was immediately struck by the diverse subjects she captured. However, it was the quality of the photographs that really struck me – the idea that not all images have to be perfect. I purchased my first 35mm camera and began experimenting, learning my craft, and taking those first steps in the world of photography.

Following my visit to New York, I curated a selection of photographs called “Instamatic Views of New York”, which were eventually exhibited in a number of spaces including Midlands Art Centre, Birmingham, Walsall Art Gallery, Walsall, and National Gallery of Film & Photography, Bradford. The support those experiences gave me provided the stepping stones for my personal and artistic growth.

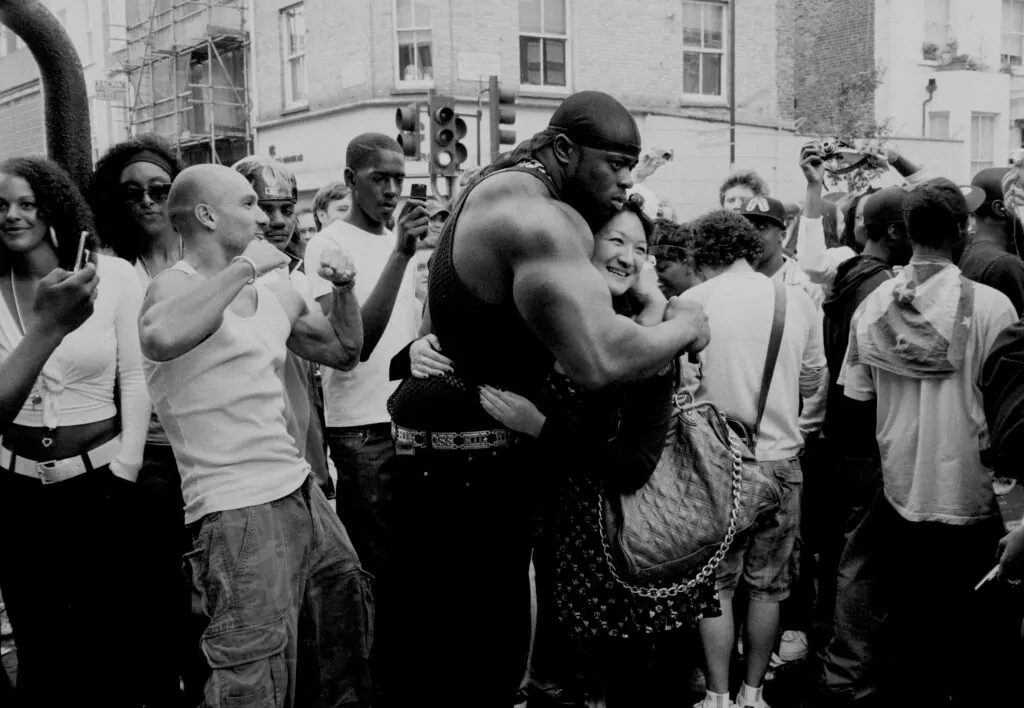

Series Schwarz Flaneur, started in 1983.

Black-and-white photograph, 35mm.

34 x 44 cm

Courtesy of the artist and OOM Gallery Archive.

Your upbringing must have had a profound influence on your work. How did these experiences shape the way you view the world and express it through art?

Pogus Caesar: The work is shaped by the diverse communities I have encountered throughout my life and travels. I have no style as each series I create is so varied, from ‘US of A’, ‘Get Naked’ and ‘Into the Light’ to ‘Schwarz Flaneur’ – my series from which a selection of works are currently on display at Ikon Gallery in Birmingham as part of its Friends in Love and War – L’Éloge des meilleur·es ennemi·es exhibition.

One has to stay fluid: challenge yourself, be fearless, and do not become complacent. Artistic mistakes are required and each hurdle provides a fragment of growth.

Series Schwarz Flaneur, started in 1983.

Black-and-white photograph, 35mm. 34 x 44cm

Courtesy of the artist and OOM Gallery

Archive.

Your work often focuses on marginalized communities and themes of social justice. How do you balance activism with artistic expression in your projects?

Pogus Caesar: My entire practice involves layering elements that relate to community and social justice whilst pushing my own artistic expression. There is always an imbalance between the two things – life is not perfect!

In your photography, you tend to favour black-and-white imagery. How does the absence of colour enhance the stories you aim to tell?

Pogus Caesar: I have always enjoyed working with black-and-white film, particularly 35mm at 400asa for its grain and how it connects with the eye. Additionally, once developed, you never know how the film will look – that is the ecstasy of anticipation. Although I have taken the photograph, the colours are very quickly forgotten; this lack of information creates a brand new narrative open to further investigation and a deeper spiritual connection.

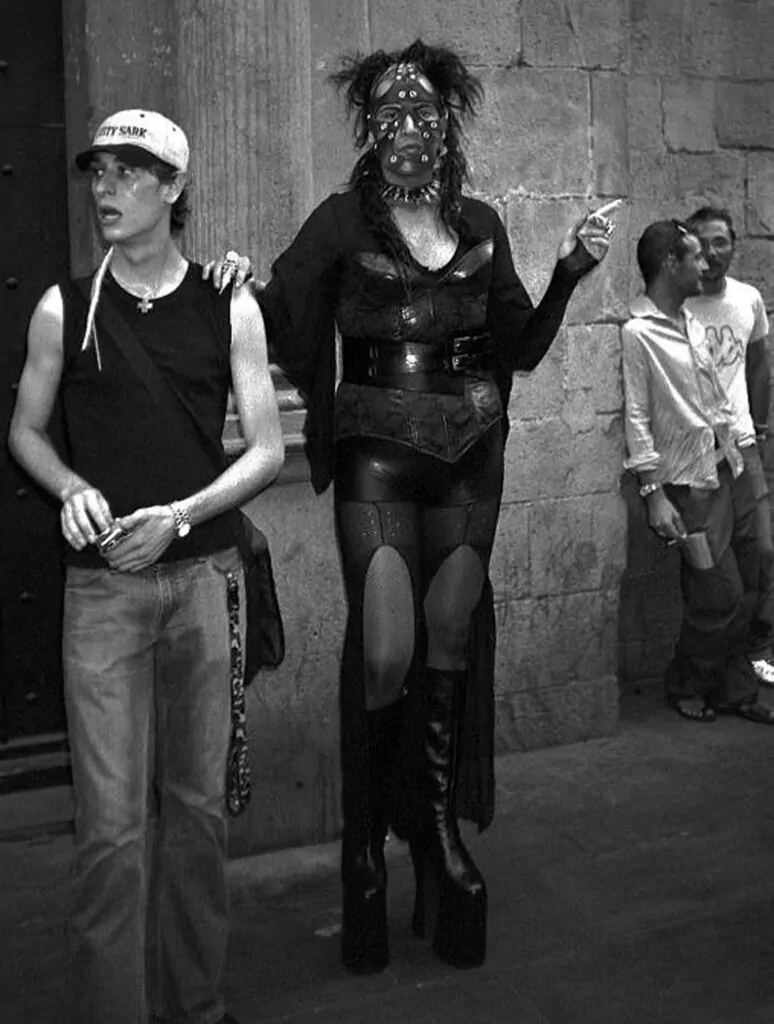

Series Schwarz Flaneur, started in 1983.

Black-and-white photograph, 35mm.

44 x 34 cm

Courtesy of the artist and OOM Gallery Archive.

Many of your photos have a raw, unfiltered quality. How important is authenticity to you, and how do you decide when a shot feels “complete”?

Pogus Caesar: To a great extent, they are raw. If shooting outside, I need the sun, which is the biggest flashbulb. For interiors, one has to find the light source and quickly build a relationship with it. There are so many images I have looked at for decades; some are not meant to be complete. You have to allow the public the responsibility of filling in the gaps.

Your Handsworth Riots series is particularly well-known. What were you trying to capture about the essence of that moment, and how do you view its relevance today?

Pogus Caesar: Regarding my photographs of the 1985 Handsworth Riots, there had been underlying tensions for years and it took a small incident to ignite the community into action. I was trying to capture my truth as I witnessed it. The atmosphere was tense with ever-changing scenarios that were totally out of anyone’s control.

It was an urban uprising, born out of frustration and other factors. Upon reflection, there were no winners, just destruction and a legacy that still resides in the underbelly of Handsworth and beyond. Throughout those few days, my equipment was an AF camera and a pocket full of film.

35mm. 34 x 44 cm.

Courtesy of the artist and OOM Gallery Archive.

The plan was to keep moving and shoot what I found relevant, no matter what the consequences were –adrenaline takes over your whole being and propels you forward in those instances. As the decades have passed, those photographic archives have become part of documentation referencing one of the most pivotal incidents to occur within the inner-cities of post-war Britain.

When photographing public events, how do you immerse yourself in the moment while maintaining an objective viewpoint as an artist?

Pogus Caesar: Once a decision is made to photograph public events, I don’t think about it too much. There is no start, stop or rewind – you get caught up in the moment and try to photograph what is relevant. No matter how objective you are, once the work is published and placed in front of the public, it takes on a completely different narrative and is open to scrutiny. You live with the scrutiny as not everyone will agree with your viewpoint or camera angle.

Pogus Caesar, Dinner Ladies, Birmingham, UK (1984)

Series Schwarz Flaneur, started in 1983.

Black-and-white photograph, 35mm. 34 x 44 cm

Courtesy of the artist and OOM Gallery Archive.

How has your role as a documentary photographer evolved with the rise of citizen journalism and the instantaneous documentation of events by everyday people?

Pogus Caesar: Well, as I am using an analogue camera, taking a photograph and instantly placing it on social media is difficult. Nonetheless, there have been moments when I have witnessed events and used my mobile phone to capture them, sharing the images on a platform for everyone to see and have an opinion on.

Series Schwarz Flaneur, started in 1983.

Black-and-white photograph, 35mm.

44 x 34 cm

Courtesy of the artist and OOM Gallery Archive.

What do you hope to leave as a legacy for future photographers and artists, particularly those from underrepresented communities?

Pogus Caesar: Leaving a legacy is an interesting notion, hopefully I can show that a skinny little black kid from the West Indies had a creative dream and followed it. I am still chasing that dream and learning how to create better, worthwhile images.

As an artist who has been active for decades, what changes in the art world have most impacted your work? How do you adapt to these shifts?

Pogus Caesar: As I still use a Canon AF 35mm camera which has 36 frames, film can be expensive and so I have learnt to be selective in what I photograph. I also must work with laboratories and printers to develop the film, which isn’t problematic as I have built up positive and longstanding relationships in those areas.

In terms of adapting, it is much easier to place your work in front of the public’s gaze now. Adapting to shifts is vital; if used correctly, they can revitalise your creative journey. Artistic complacency is not part of my thought process.

What advice would you give to young photographers and artists who wish to capture social justice issues through their work?

Pogus Caesar: Just continue documenting. Create and archive visual personal diaries. We are witnessing times where images of social justice issues will play a vital part in world history. The more photographic images there are, the more future generations can hopefully attempt to piece together a road map of the times we are presently living in.

Everyone has a smartphone camera: you are a broadcaster with two video camera ‘eyes’, two stereo speaker ‘ears’, one microphone ‘mouth’, and a very powerful and complex hard drive ‘brain’. All those elements combined make you and your work an unstoppable force.

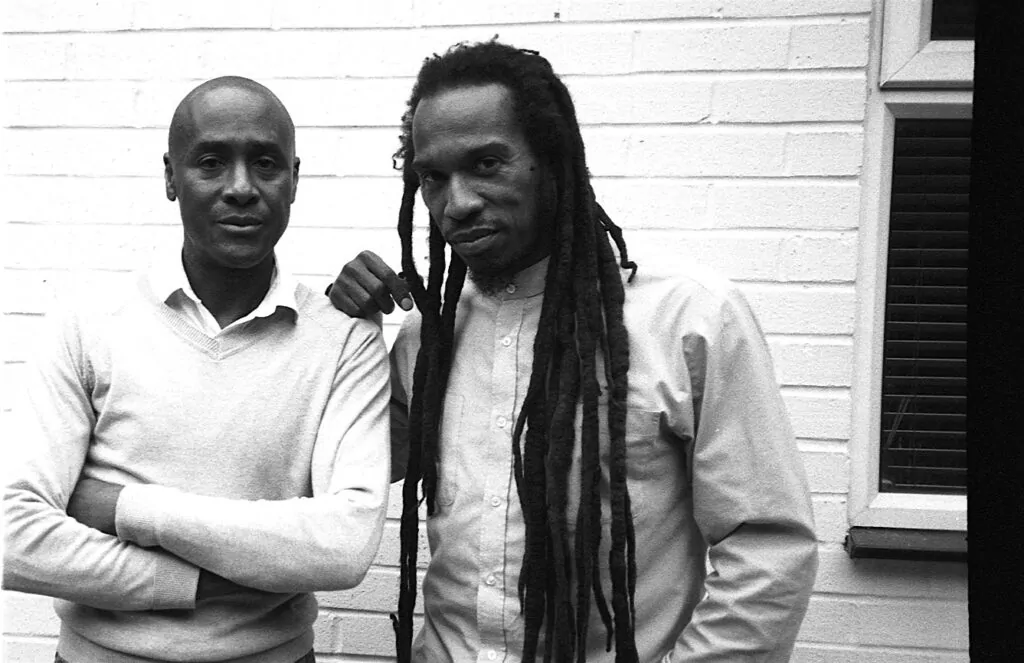

Series Schwarz Flaneur, started in 1983.

Black-and-white photograph, 35mm.

34 x 44 cm

Courtesy of the artist and OOM Gallery

Archive.

In a world saturated with images through social media and smartphones, how do you preserve the power and uniqueness of your work?

Pogus Caesar: Undoubtedly, social media and smartphones are an unstoppable force and will continue to develop at a rapid pace. One has to embrace technology and, when required, use it in one’s practice. While the majority of my photographic work is 35mm film, I am working in a digital timeframe – it is about balance and not allowing the technology to grasp the creativity out of your hands.

In terms of preserving the work, a large percentage of it comprises ordinary everyday moments. To an extent, that is quite mundane. However, the images are also a testament to my life, in which I have had the good fortune to journey into territories and document a broad range of cultures.

© Pogus Caesar/ OOM Gallery Archive/DACS/Artimage

Lastly, could you share the philosophy that guides your art and how you view its core importance in your life and career?

Pogus Caesar: There is a simple philosophy I adhere to: try not to worry about the public not connecting with your work and capture what you find interesting as in years to come the images may become relevant.

Every image is a historic document of the era we are living in. In time, the images may accelerate to a position where they achieve cultural value.

Finally, have no fear, as not everyone will understand your vision; if 60% do, that is a start.

Friends in Love and War — L’Éloge des meilleur·es ennemi·es is presented at Ikon Gallery in collaboration with macLYON as part of the British Council’s UK/France Spotlight on Culture 2024, 2 October 2024 – 23 February 2025. ikon-gallery.org

©2024 Pogus Caesar