Singaporean curator John Tung‘s curatorial approach is a rigorous process of in-depth research, collaborative conversation, and shared ideas as he strives to spark new discussions around pressing contemporary issues.

A respected figure within the Southeast Asian art scene, Tung held an influential role at the Singapore Art Museum as an assistant curator from 2015 to 2020.

During this period, he curated and co-curated numerous exhibitions, making significant contributions to the Singapore Biennale, for the Biennale’s 2016 edition, An Atlas of Mirrors, and the 2019 edition, Every Step in the Right Direction.

Playing a crucial role in shaping the Biennale’s most influential narratives, with three of the commissions under his curation being shortlisted for the Benesse Prize and one ultimately secured the award.

In his latest curatorial project, Déjà vu: Buddha is Hiding, in collaboration with the highly regarded Thai artist Natee Utarit and exhibited at Singapore’s STPI, the exhibition explores a hypothetical journey of Buddha to the West, examining how colonial conditioning has shaped perceptions of Eastern spirituality.

Under Tung’s direction, exhibitions are intellectually and emotionally grounded, a product of his belief that art should engage not just the eye, but also the mind and soul. He continues to push the boundaries of what a curator can be, crafting exhibitions that are as much about the questions they raise as the answers they may—or may not—provide.

Image by Colin Wan

Courtesy Art Outreach Singapore

I began to realise the significance of storytelling as a means to enact positive social change in the most democratic manner

John Tung

Hi John, thanks for speaking with us! Could you start by sharing your journey into the arts and curation? What were some of the pivotal moments or key influences that significantly shaped your path as a curator?

John Tung: My exposure to the arts began at a young age. I must have been 6 when I was thrust into speech and drama classes by my parents – who, like most Asian parents then, were hoping to reap the positive externalities of being trained in drama, rather than producing a thespian. Life of course had other plans, and I ended up making the appetizer my main course. While I was certain I wanted to be in some ways involved in the arts as a career by the time I was a teenager, I really only started embracing it fully when I embarked on my stint at the Singapore Art Museum as an Assistant Curator.

I had always been in love with storytelling. But it was only after my postgraduate studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong where I focused on cultural policy, that I began to realise the significance of storytelling as a means to enact positive social change in the most democratic manner. I also bought in wholeheartedly into SAM’s (then) vision of “Inspiring humane and better futures”. I saw exhibitions as a way of sharing ideas, inviting discourse, and – perhaps most importantly – giving the people the option of buying into ideals.

As such, I think my curatorial approach can be seen as a tad – God-forbid – didactic. Afterall, my curatorial impetus was shaped by my former Professors, Prof. Oscar Ho and Prof. Benny Lim from CUHK, and my ever-mentor, Dr Susie Lingham formerly Director of SAM.

flocking on linen, 161.3 x 129 cm each. © Natee Utarit / STPI. Photo courtesy of the artist and

STPI – Creative Workshop & Gallery, Singapore.

Moving on to your approach as a curator, could you discuss how you select themes, artists, and artworks for exhibitions? Additionally, what factors influence the layout and overall presentation of an exhibition?

John Tung: With respect to themes, artists, and artworks, I would say the criteria I prioritise are significance, relevance, and authenticity respectively. I believe it is of paramount importance to focus energies on making exhibitions expressing urgent themes to the contemporary circumstance, seeking insight from artists whose practices exemplify engagement with the relevant ideas, and selecting works that the artists are themselves absolutely committed to.

The layout and exhibition design should always prioritise the requirements of the particular works in the exhibition. And while I do waver between clean spartan spaces in some exhibitions, to complicated scenography and unorthodox hanging methods in others, it is always done with the blessings of the artists and to draw out the appropriate responses from audiences when they encounter the works.

Reflecting on your extensive experience with curating exhibitions that explore cultural dialogues, such as An Atlas of Mirrors and the Déjà vu series, how do you approach curating works that juxtapose Eastern and Western imagery? What are some of the critical considerations in ensuring that this juxtaposition is not only visually impactful but also conceptually coherent?

John Tung: Reading around the art, and not just reading about the art itself. The contemporary curator has the significant challenge of being expected to be a subject matter expert in the same subjects that the artists are engaged with. Even if expertise is too much to expect, I believe there should necessarily be a minimum threshold. And that threshold is being able to ascertain if a concept holds water.

Then, with respect to the juxtaposition of Eastern and Western imagery/themes/concepts, and so forth, in contemporary exhibitions and artmaking, the necessary question that should follow is: when is juxtaposition, hybridisation? And are we speaking of the perceived East-West dichotomy in geographical terms, geopolitical terms, cultural terms, or historical terms rooted in colonial thought? Moreover, what timeframes are we speaking with reference to? We presently live on an irregularly shaped ellipsoid where everything Far-East enough inevitably ends up being West again. I would like to say drawing lines is a largely colonial occupation, but that would be a disservice to Qin Shi Huang who literally built a line to demarcate the space between us and them.

The important thing about cultural dialogues then really becomes about determining which lines are arbitrary.

cm. © Natee Utarit / STPI. Photo courtesy of the artist and STPI – Creative Workshop &

Gallery, Singapore.

In curating Utarit’s exhibition, which concludes his Déjà vu series, how did you interpret his imagined journey of Buddha to the West within a contemporary art context? What role do you think this hypothetical narrative plays in addressing postcolonial identity and cultural exchange in today’s globalized art world?

John Tung: Rather than interpretation, I like to think I seek out points of reference – circumstances that parallel the ideas I am certain the work embodies. This takes the debate of whether there is truth in interpretation out of the equation.

I mentioned the notion of hybridisation earlier. It surprises most people that some of the earliest depictions of the Buddha in sculpture – the Gandara Buddhas from the 1st to 5th centuries CE – are the result of syncretism between Greek art and Buddhism. It arose from exchanges that commenced even earlier, beginning with Alexander the Great’s incursions into the Indian subcontinent. On the other hand, it also surprises most people to discover that the Mindfulness movements that proliferate in the West (but really… globally) has its roots in secularised Buddhist meditation techniques.

In this respect, the images arising from Utarit’s hypothetical narrative emerge as juxtapositions only to the extent that they reflect the contemporary post-colonial circumstance of being blissfully ignorant, or perhaps more accurately, apathetic of origins. We are still embroiled in drawing imaginary lines so as to stake claims of ownership.

Photo courtesy of the artist and STPI – Creative Workshop & Gallery, Singapore.

In your role as a curator of nearly 50 exhibitions and hundreds of site-specific adaptations, how do you balance the artistic intent of an artist like Utarit with the broader exhibition theme? In this case, how did you negotiate between his vision for the Déjà vu series and your curatorial framework?

John Tung: I am of the belief that the fundamental role of the curator is to clarify the intentions of the artist, and whatever curatorial embellishments that come after should be just that – but never detracting from the original intention of the work. While one could argue that the job of the curator might also be to open up new avenues and creating new contexts for the understanding of a particular work or body of work, another could also say that this still cannot reveal anything more that was not present in the work to begin with.

I am a big believer in conversation and finding as much as I can around the work in addition to the work itself. My conversations with Natee in the lead up to the exhibition spanned topics ranging from tea ware to bonsai, exchanges specific to the exhibition to random unrelated anecdotes from our daily lives. I think all of these conversations allow for a more holistic view of the big picture, and synchronisation of the curatorial approach to the needs of the artist and the works.

Negotiations, specifically those of a conceptual nature, would suggest a misalignment between curator and artist. I don’t think artists should negotiate with curators, and likewise, curators should not negotiate with artists. An exhibition should necessarily be a shared vision.

Utarit’s works in the Déjà vu series are characterized by their innovative use of print and paper. How did his collaboration with STPI impact your curatorial decisions for this exhibition? What challenges or opportunities did this collaboration present in terms of presenting new media within a historical narrative?

John Tung: Just to clarify: there are pre-existing works in the Déjà vu series that are not print and paper. It is only the STPI Déjà vu works that employ paper exclusively.

A core characteristic of print is its reproducibility. Buddha is Hiding is the first time I had the opportunity to curate so many variations of similar pieces in a single exhibition. While it could be argued that variations would be inevitable with each work — even if reproduction was the goal — both Utarit and I believed that this characteristic of reproducibility should be a key attribute communicated to audiences with this body of works. This led to multiple variations of what was essentially the “same” work being put on display eventually.

Print confers a very different quality from painting. Where the uniqueness of a painting limits its reach — owing it to being unable to be in more places than one — the multiplicity of prints allows for presentation across a number of spaces. Not unlike the Gutenberg bible, this quality is suggestive of information that needs urgent dissemination.

I wanted to recognise this quality, while also honouring the inherent uniqueness present in each of the variations, and decided to line all the variations of one particular series up in a row.

linen, 161.3 x 129 cm. © Natee Utarit / STPI. Photo courtesy of the artist and STPI – Creative

Workshop & Gallery, Singapore.

Finally, with your experience curating large biennales and smaller independent exhibitions, how did you approach creating a cohesive narrative within Utarit’s body of work for this exhibition? What role did individual artworks play in shaping the overall structure of the exhibition, and how did you ensure that the thematic depth of the Déjà vu series was fully realized?

John Tung: With Buddha is Hiding, the body of work that Utarit developed was already exceedingly cohesive. Individual works in the series here played the role of articulating and elaborating further on the themes that he has already spent innumerable hours considering. In that respect, my goal was to find a method of organisation that could bring these themes to the fore, and at the same time arrive at an exhibition layout and lighting design that would subtly intimate ideas of excavation, research, and study.

After arriving at a coherent sorting of the artworks for presentation in STPI gallery’s various wings, the most time was spent deliberating sightlines for the positioning and encounter of the works. I had wanted to strike a balance between the initial encounter – from a distance and then close-up – and the re-encounter of the work — for devoted audiences who’d circle the gallery multiple times in different directions. Rather than organisation of the works along a linear narrative with a directed flow through the venue, I relied on iteration and re-iteration (from the encounters of variations of works) to drive Utarit’s message home.

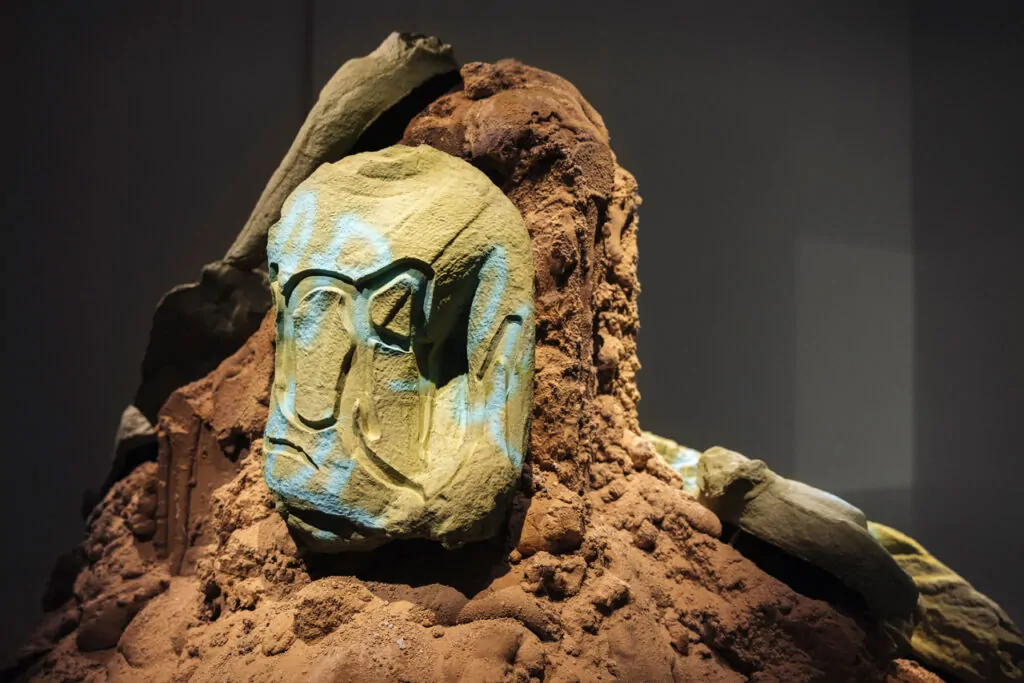

The bright defused lighting of the main gallery sought to mimic an atmosphere of scientific study, contrasting the presentation context of a final suite of paper mâché sculptures tucked away in a more atmospherically lit private viewing room. Here, a suite of Buddha torsos, previously encountered clinically mounted outside, are presented seemingly freshly excavated – perhaps just released from the clutches of Roman soil…

As I mentioned earlier, I do tend to waver between spartan presentations and complicated scenographies across my projects. And so I thought this time, why not a little bit of both at once? (:

©2024 John Tung